Archive

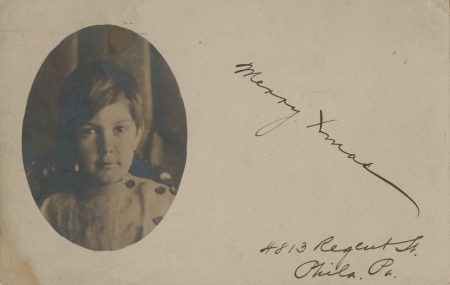

Calder is born in Lawnton, Pennsylvania, to Nanette Lederer Calder, a painter, and Alexander Stirling Calder, a sculptor. I always thought I was born—at least my mother always told me so—on August 22, 1898. But my grandfather Milne’s birthday was on August 23, so there might

have been a little confusion. In 1942, when I wrote the Philadelphia City Hall for a birth certificate, I sent them a dollar and they told me I was born on the twenty second of July, 1898. So I sent them another dollar and told them, “Look again.” They corroborated the first statement.

1902

Calder poses for his father’s sculpture, Man Cub, in Philadelphia. Calder sculpts his own clay elephant.

Calder 1966, 13

1905

Stirling Calder contracts tuberculosis. Calder’s parents move to a ranch in Oracle, Arizona, leaving Calder and his sister Peggy in the care of Dr. Charles P. Shoemaker, a dentist, and his wife, Nan.

Calder 1966, 15; Hayes 1977, 18

1906

Nanette picks up Calder and Peggy and they rejoin their father in Oracle. Calder befriends Riley, an elderly man recuperating at the ranch who shows him “how to make a wigwam out of burlap bags pinned together with nails.”

Calder 1966, 16

The Calders move to Pasadena, California. At that time, on Euclid Avenue in Pasadena, I got my first tools and was given the cellar with its window as a workshop. Mother and father were all for my efforts to build things myself—they approved of the

homemade . . . My workshop became some sort of a center of attraction; everybody came in.

My sister had quite a few dolls for which we made extraordinary jewelry from beads and very fine copper wire that we found in the street left over by men splicing electric cables.

Calder 1952, 37Peggy once gave me a very nice pair of pliers at Christmas. I made her a little Christmas tree, completely decorated, out of a fallen branch. So she wept because my gift was homemade.

Calder 1966, 211907

Calder attends Pasadena’s Tournament of Roses, where he experiences the four-horse chariot races.

Calder 1966, 221909

The Calders move to a new house on 555 Linda Vista Avenue. Calder’s workshop consists of a tent with a wooden floor. Calder attends fourth grade at Garfield School.

CF, Nanette to Trask, 30 March; Calder 1966, 26–27The Calders return to Philadelphia. Calder attends Germantown Academy for two or three months while his parents search for a house close to New York City.

Calder 1966, 28; CF, Calder 1955–56, 7The Calders move to Croton-on-Hudson, New York. Calder has a cellar for his workshop and attends Croton Public School.

Calder 1966, 28–29For Christmas, Calder presents his parents with a dog and a duck that he trimmed from a brass sheet and bent into formation. The duck is kinetic, rocking back and forth when tapped.

Sweeney 1943, 57; Hayes 1977, 411910

For his father’s birthday, Calder makes Animal Zoo Puzzle, a game consisting of five painted animals—a tiger, a lion, and three bears—and a wooden board with nails divided into six pens. The challenge is to move the animals from their pens without having two animals in the same pen at once.

Hayes 1977, 421912

The Calders move to Spuyten Duyvil, New York. The cellar becomes Calder’s workshop. Calder and Peggy attend Yonkers High School. Stirling rents a studio in New York City on 51 West Tenth Street.

Calder 1966, 34–35Stirling is appointed as the acting chief of the department of sculpture of the Panama-Pacific International Exposition in San Francisco. He writes the introduction to The Sculpture and Mural Decorations of the Exposition, published in 1915.

Calder 1966, 36

1913

The Calders move to San Francisco. Calder has a workshop in the cellar and attends Lowell High School.

Calder 1966, 36–37; Hayes 1977, 43–441915

Stirling and Nanette move to Berkeley to be near Stirling’s next commission, the Oakland Auditorium. Calder stays with the architect Walter Bliss and his wife to graduate from Lowell High School.

Calder 1966, 37–38; Hayes 1977, 52–53; CF, Calder 1955–56, 14The Calders move back to New York City on Claremont Place.

Calder 1966, 39; Hayes 1977, 55Calder begins his studies at Stevens Institute of Technology, Hoboken, New Jersey, where he takes courses that include chemistry, mechanical drawing, shop practice, and surveying, among others.

Calder 1966, 391916

Calder spends five weeks in the Plattsburg Civilian Military Training Camp, New York, drilling with Company H, Fifth Training Regiment.

Calder 1966, 461918

Calder joins the Student Army Training Corps, Naval Section, at Stevens, where he is made guide of the battalion.

Calder 1966, 481919

Calder graduates from Stevens with a degree in mechanical engineering.

CF, certificate of graduation; Lipman 1976, 329Calder holds jobs with an automotive engineer named Tracy in Rutherford, New Jersey, and with New York Edison Company as a draftsman.

Calder 1966, 48–491920

Calder joins the staff of Lumber magazine in St. Louis, Missouri. He stays for nine months.

Calder 1966, 48–501921

Calder works for Nicholas Hill, a hydraulics engineer, coloring maps for a water-supply project in Bridgeport, Connecticut. The efficiency engineers—Miller, Franklin, Basset, and Co.—hire Calder to do fieldwork for the Truscon Steel Company in Youngstown, Ohio.

Calder 1966, 49–501922

Calder attends night classes in drawing with Clinton Balmer at the New York Public School on Forty-second Street.

Calder 1966, 51Serving on the H.F. Alexander as a fireman in the boiler room, Calder sails from New York to San Francisco via the Panama Canal. It was early one morning on a calm sea, off Guatemala, when over my couch—a coil of rope—I saw the beginning of a fiery red sunrise on one side and

the moon looking like a silver coin on the other. Of the whole trip this impressed me most of all; it left me with a lasting sensation of the solar system.

Arriving in San Francisco, Calder takes a lumber schooner to Willapa Harbor, Washington, where he catches the bus for Aberdeen and meets his sister Peggy and her husband, Kenneth Hayes. Calder finds a job as a timekeeper for a logging camp in Independence, Washington.

I was supposed to make out paychecks for people. I also had to scale the logs as they were loaded on the flatcars.

Inspired by the logging camp landscape, Calder writes home and asks his mother for paints and brushes.

CF, Calder 1955–56, 39; Calder 1966, 57–581923

With the help of Stirling’s introduction, Calder seeks employment with an engineer in Canada. I went to Vancouver and called on him, and we had quite a talk about what career I should follow. He advised me to do what I really wanted to do—he himself often wished he had been an

architect. So, I decided to become a painter.

Calder writes the Kellogg Company and suggests they modify their cereal packaging, putting the wax paper on the inside rather than on the outside of the boxes. The company adopts his suggestion and sends him a note of thanks along with a case of Corn Flakes.

Hayes 1977, 76Calder returns to New York and stays with his parents at 119 East Tenth Street.

Calder 1966, 59Calder begins classes at the Art Students League of New York, studying life and pictorial composition with John Sloan and portrait painting with George Luks.

Calder 1966, 59–61, 66–67; ASL, registration records1924

Calder enrolls again at the Art Students League, taking classes in portrait painting with George Luks, head and figure with Guy Pène du Bois, a drawing class with Boardman Robinson, and an etching class.

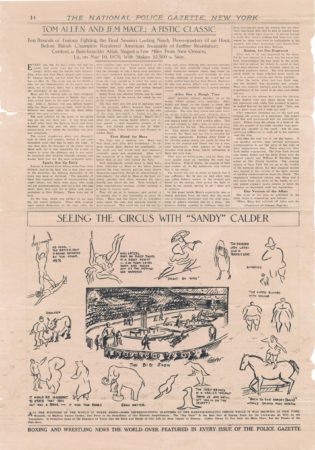

ASL, registration recordsCalder begins his first job as an artist, illustrating sporting events and city scenes for the National Police Gazette.

Calder 1966, 67; Gazette, 3 MayCalder moves into his father’s studio, 11 East Fourteenth Street, while his parents are traveling in Europe.

Calder 1966, 66, 70; Hayes 1977, 81Calder studies life drawing with Boardman Robinson at the Art Students League.

ASL, registration records1925

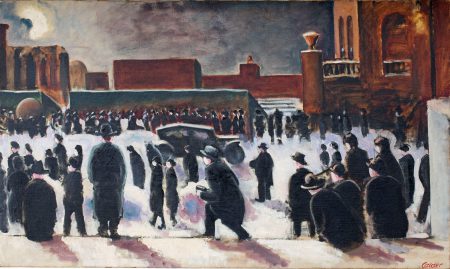

A total eclipse of the sun is visible from the northern part of Manhattan. Along with thousands of New Yorkers, Calder travels uptown, stopping at the steps of Columbia University to watch. He makes The Eclipse, an oil painting of the scene.

New York Times, 24 January; CF, object fileCalder studies life drawing with Boardman Robinson at the Art Students League.

ASL, registration recordsCalder exhibits The Eclipse in the Ninth Annual Exhibition of the Society of Independent Artists at the Waldorf-Astoria, New York. In the exhibition catalogue he lists his address as 119 East Tenth Street, where he periodically lives with his parents.

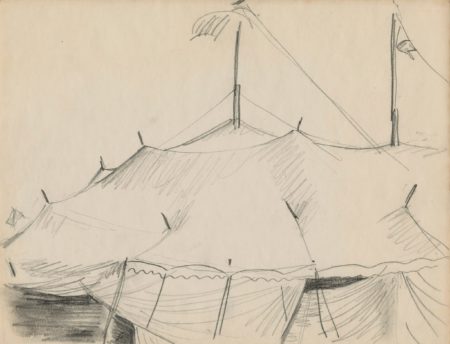

CF, exhibition fileCalder spends two weeks illustrating the Ringling Bros. and Barnum & Bailey Circus for the National Police Gazette. I could tell by the music what act was getting on and used to rush to some vantage point. Some acts were better seen from above and others from below.

Calder 1966, 73; Gazette, 23 May

Calder makes hundreds of brush drawings of animals at the Bronx Zoo and the Central Park Zoo.

CF, object files; Sweeney 1951, 72Calder takes a lithography class with Charles Locke at the Art Students League.

ASL, registration recordsCalder travels to Florida. First he visits Miami, then Sarasota, where he sketches at the winter grounds of the Ringling Bros. and Barnum & Bailey Circus. I was very fond of the spatial relations. I love the space of the circus. I made some drawings of nothing but the tent. The whole

thing of the—the vast space—I’ve always loved it.

1926

Artists Gallery, New York, includes an oil painting by Calder in a group exhibition. Murdock Pemberton, the art critic for the New Yorker, comments on the exhibition: A. Calder, too, we think is a good bet.

CF, exhibition file; Pemberton 1926While renting a room in the apartment of Alexander Brook, assistant director of the Whitney Studio Club, Calder embellishes the Brook children’s “Humpty Dumpty Circus.” He adds movement and articulation to the set of store-bought toys, making an elephant that could “go round

a circle” and a mechanism that could “hoist a clown on his back.”

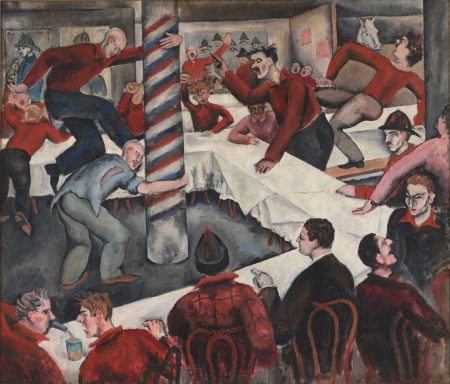

American painter Walter Kuhn organizes a stag dinner at the Union Square Volunteer Fire Brigade, Tip Toe Inn, New York, in honor of sculptor Constantin Brancusi’s first visit to the United States. Calder paints Firemen’s Dinner for Brancusi commemorating the event.

Geist 1976; AAA, Louis Bouché Papers, dinner invitation; CF, object fileCalder sketches a human dissection at Physicians and Surgeons Hospital. I drew for several hours and subsequently painted The Stiff . . . I went to a party that evening and kept asking if I did not smell of forma(h)ldehide—my hair, particularly. They said “no”—but

the odor was with me—and although I really intended returning, I never did.

Calder exhibits The Stiff in the Tenth Annual Exhibition of the Society of Independent Artists at the Waldorf-Astoria, New York.

CF, exhibition fileCalder exhibits an oil painting at the Whitney Studio Club Eleventh Annual Exhibition of Paintings and Sculpture by Members of the Club, Anderson Galleries, New York.

CF, exhibition fileAt his friend Betty Salemme’s house on Candlewood Lake in Sherman, Connecticut, Calder carves his first wood sculpture, Very Flat Cat, from an oak fence post.

CF, Calder 1955–56, 174Calder moves into a tiny, one-room apartment at 249 West Fourteenth Street. There he makes his first wire sculpture, a sundial in the form of a “rooster on a vertical rod with radiating lines at the foot” to demarcate the hours.

Hayes 1977, 90; Calder 1966, 71–72Animal Sketching, a drawing manual written by Calder with reproductions of 141 of his brush drawings, is published by Bridgman Publishers in New York and The Bodley Head in London.

CF, project fileCalder exhibits The Horse Show in an exhibition on the subject of the horse at the Anderson Galleries, New York, curated by Karl Freund.

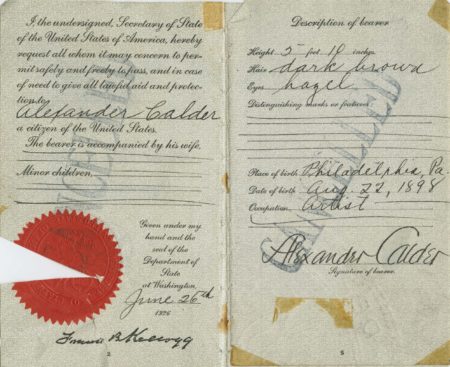

CF, exhibition fileCalder receives his U.S. passport in preparation for his first voyage to Europe.

CF, passport

With the help of his former teacher, Clinton Balmer, Calder signs on to the crew of the Galileo, a British freighter sailing for Hull, England. He works as a laborer, painting the exterior of the ship.

Calder 1966, 76–77; CF, Calder to parents, 18 JulyCalder arrives in Hull, spends one night, and takes the noon train to London.

CF, Calder to parents, 18 JulyCalder arrives in London and stays four nights with Bob Trube, his fraternity brother from Stevens.

CF, Calder to parents, 26 JulyCalder leaves England, taking the 10 a.m. train from Victoria Station to New Haven and the ferry to Ville de Dieppe in France. He arrives in Paris and calls on Trube’s father at the Hôtel de Versailles, 60 boulevard de Montparnasse. [Trube] had written his dad to look out for

me. So I got a room here at 35F and am on the 7th floor with a French window that gives fine light and air and a red rug and brown wallpaper that would knock your eye out. Also an upright piano.

At the Café du Dôme, a meeting place for artists and their dealers, Calder recognizes American painter Arthur Frank, an acquaintance from New York, and meets British printmaker Stanley William Hayter, whose wife he knew from the Art Students League.

Calder 1966, 78Calder enrolls in drawing classes at the Académie de la Grande Chaumière.

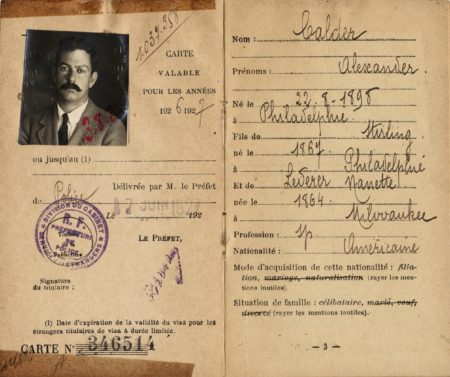

Calder 1966, 78Calder’s French identity card is issued for 1926–27.

CF, carte d'identité

Calder establishes a studio at 22 rue Daguerre.

CF, Calder to parents, c. 26 AugustCalder is hired to leave France for a quick round-trip voyage on the SS Volendam Holland America Line; he sketches life on board the ship for the Student Third Cabin Association’s poster and advertising brochure.

Calder 1966, 79; CF, Calder to parents, 26 AugustCalder arrives in New York on the SS Volendam.

CF, Calder to parents, c. 26 AugustCalder arrives at Boulogne-sur-Mer, France, on the SS Volendam.

CF, Calder to parents, 25 and 27 SeptemberCalder travels by train to Paris from Boulogne-sur-Mer.

CF, Calder to parents, OctoberCalder meets Lloyd Sloane, an advertising executive, who introduces him to staff at Le Boulevardier, including Marc Réal, artistic advisor. Several of Calder’s drawings are published in Le Boulevardier over the next few months.

Calder 1966, 83Calder meets a Serbian toy merchant who encourages him to make mechanical toys for mass production.

Calder 1966, 80; CF, Calder 1955–56, 44Through Hayter, Calder meets José de Creeft, a Spanish sculptor living on rue Broca. De Creeft suggests to Calder that he submit his toys to the “Salon des Humoristes.”

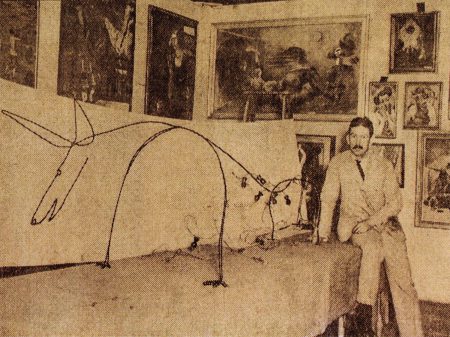

Calder 1966, 80Calder begins creating Cirque Calder, a complex and unique body of art. Fashioned from wire, fabric, leather, rubber, cork, and other materials, Cirque Calder is designed to be performed for an audience by Calder. It develops into a multi-act articulated series of mechanized sculpture in miniature scale, a distillation of the natural circus.

Calder is able to travel with his easily transportable circus and hold performances on both continents. Over the next five years, Calder continues to develop and expand this work of performance art to fill five large suitcases.

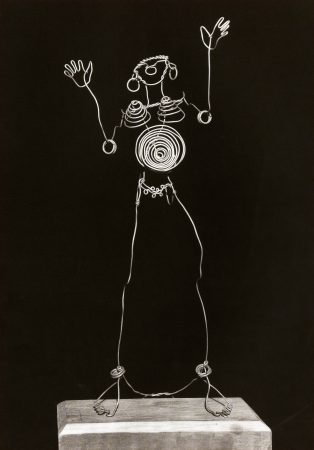

Calder makes his first formal wire sculptures, Josephine Baker I and Struttin’ His Stuff.

Calder 1966, 80–81; CF, Calder 1955–56, 45Calder performs Cirque Calder for Mrs. Frances C. L. Robbins, a patron of young artists. On her recommendation, English novelist Mary Butts comes to see it and in turn sends Jean Cocteau to a performance.

CF, Calder 1955–56, 68; Hawes 19281927

Calder exhibits toys in the “Salon des Humoristes” at Galerie de la Boétie, Paris.

CF, exhibition fileRéal brings Guy Selz and the circus critic, Legrand-Chabrier, to see Calder perform Cirque Calder. Legrand-Chabrier admires Calder’s work and writes several articles on the Cirque. Oh, these are stylized silhouettes, but astonishing in their miniature resemblance,

obtained by means of luck, iron wire, spools, corks, elastics . . . A stroke of the brush, a stroke of the knife, of this, of that; these are the skillful marks that reconstruct the individuals that we see at the circus.

Here is a dog who seems like a prehistoric cave drawing with a body of iron wire. He will jump through a paper hoop. Yes, but he may miss his mark or not. This is not a mechanical toy . . .

All of this is arranged and balanced according to the laws of physics in action so that it allows for the miracles of circus acrobatics.

Calder renews his French identity card.

CF, carte d'identitéGalleries of Jacques Seligmann and Company, Paris, exhibits animated toys by Calder.

CF, exhibition file; Comoedia, 29 AugustThe New York Herald, Paris, publishes an article about Calder and his decision to make toys: I began by futuristic painting in a small studio in the Greenwich Village section of New York. It was a lot different to engineering but I took to my newfound art immediately. But it seemed that

during all of this time I could never forget my training at Stevens, for I started experimenting with toys in a mechanical way. I could not experiment with mechanism as it was too expensive and too bulky so I built miniature instruments. From that the toy idea suggested itself to me so I figured I might as well turn my efforts to something that would bring remuneration. From then on I have constructed several thousand workable toys.

Calder returns to New York and stays with his parents at 9 East Eighth Street.

CF, Calder 1955–56, 46; Calder 1966, 86Calder travels to Oshkosh, Wisconsin, to contract with Gould Manufacturing Company. He designs prototypes for a series of plywood animal Action Toys.

Calder 1966, 83–85; CF, Pajeau to Calder, 12 NovemberCalder returns to New York and rents a room at 46 Charles Street where he gives Cirque Calder performances.

Calder 1966, 87; CF, Calder 1955–56, 461928

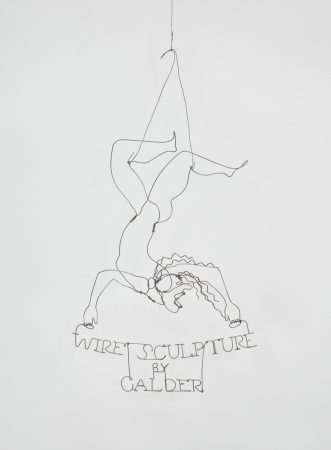

Weyhe Gallery, New York, exhibits “Wire Sculpture by Alexander Calder.” Calder creates a hanging sign, Wire Sculpture by Alexander Calder, for the gallery window. Pioneer Woman is sold to Marie Sterner, an art dealer.

CF, exhibition file; CF, Calder 1955–56, 25Calder exhibits four sculptures, including Romulus and Remus and Spring, in the Twelfth Annual Exhibition of the Society of Independent Artists at the Waldorf-Astoria, New York.

CF, exhibition file

ACME Film Company produces Sculptor Discards Clay to Ply His Art in Wire, a film of Calder’s wire sculpture that includes footage of Calder creating a wire portrait of Elizabeth “Babe” Hawes, a reporter and aspiring fashion designer whom he had met in Paris.

CF, project file

Calder spends the summer working on wood and wire sculptures at the Peekskill, New York, farm of J. L. Murphy, the uncle of fraternity brother Bill Drew. I worked outside on an upturned water trough and carved the wooden horse bought later by the Museum of

Modern Art, a cow, a giraffe, a camel, two elephants, another cat, several circus figures, a man with a hollow chest, and an ebony lady bending over dangerously, whom I daringly called Liquorice.

Hawes establishes a couture house at West Fifty-sixth Street in New York. Calder occasionally designs neckpieces and other accessories for her clothing.

Hawes 1938, 134–36; Berch 1988, 34–35The French Consulate, New York, grants Calder a visa.

AAA, passportCalder arrives at Le Havre after a voyage from New York on the De Grasse. He returns to Paris, where he rents a small building behind 7 rue Cels to use as his studio. When I returned to Paris in Nov. 28 I was a “wire sculptor” as I put it, also “le roi du fil de fer.”

AAA, passport; Calder 1966, 91; CF, Calder 1955–56, 49At the Café du Dôme, Paris, Calder sees his acquaintance, painter Yasuo Kuniyoshi, and meets “a small man in a bowler hat,” who he learns is painter Jules Pascin, a friend of Stirling’s.

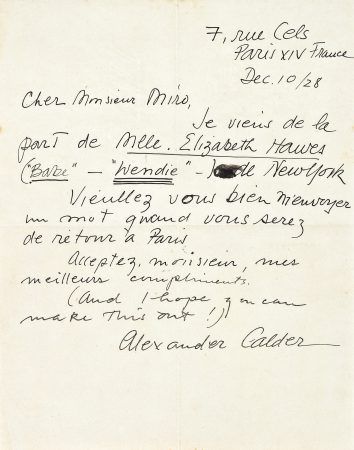

Calder 1966, 91At the recommendation of Hawes, Calder writes to Joan Miró in Montroig, Spain, suggesting that they meet when Miró returns to Paris.

Calder 1966, 92; FJM, Calder to Miró, 10 December

Calder visits Miró at his Montmartre studio, a sort of metal tunnel, a kind of Quonset hut. Miró has no paintings in the studio, but he shows Calder a collage, a big sheet of heavy gray cardboard with a feather, a cork, and a picture postcard glued to it. There were probably a few

dotted lines . . . I was nonplussed; it did not look like art to me. Later, Miró attends Cirque Calder at Calder’s rue Cels studio. Miró says, “I liked the bits of paper best.” These are little bits of white paper, with a hole and slight weight on each one, which flutter down several variously coiled thin steel wires, which I jiggle so that they flutter down like doves onto the shoulder of a bejeweled circus belle dame.

1929

Calder exhibits Romulus and Remus and Spring at the Salon de la Société des Artistes Indépendants, Paris. The public reaction is a mixture of confusion and delight. One critic remarks, At first, I believed that electricians had forgotten their electrical wire in this room, but

as I passed, a wire became agitated and I noticed that it represented the head of a she-wolf. Another tangle of electrical wire represented, by all evidence, a giant young woman. Another critic advises, All the same, look at them. Who knows if the sculpture of Mr. Calder is not that of the future? In any case, it doesn’t spawn melancholy.

Galerie Billiet-Pierre Vorms, Paris, exhibits “Sculptures bois et fil de fer de Alexandre Calder.” Pascin writes the preface for the exhibition catalogue:

By some miracle, I became a member of a group of Aces of American Art, a Society of very successful painters and

sculptors!!!

—The fortunes of the life of an itinerant painter!

The same luck led me to meet the father Stirling Calder.

Away from New York at the time of our exhibition, I cannot testify to the success of our effort; but in any case, I can attest that Mr. Stirling Calder, who is one of our best American sculptors, is also the handsomest man in our Group.

Returning to Paris, I met his son SANDY CALDER, who at first sight left me quite disillusioned. He is less handsome than his Dad! Honestly!!!

But in the presence of his works, I know that he will soon make his mark; and that despite his appearance, he will exhibit with spectacular success alongside his Dad and other great artists like me, PASCIN, who’s talking to you . . . !

In writing about his own history of wire sculpting, Calder notes a change in his approach to the medium: Before, the wire studies were subjective, portraits, caricatures, stylized representations of beasts and humans. But these recent things have been viewed from a more

objective angle and although their present size is diminutive, I feel that there is no limitation to the scale to which they can be enlarged . . . There is one thing, in particular, which connects them with history. One of the canons of the futuristic painters, as propounded by Modigliani, was that objects behind other objects should not be lost to view, but should be shown through the others by making the latter transparent. The wire sculpture accomplishes this in a most decided manner.

In a review of Calder’s solo show at Galerie Billiet-Pierre Vorms, Paris, the phrase “drawing in space” is coined to describe Calder’s wire sculptures. Horses rear up, riders brace themselves, dancers throw to the sky legs more rigid than doorbell wires. It looks like a drawing in space. On

the following day, Paul Fierens uses the phrase to describe Romulus and Remus and Spring at the Salon de la Société des Artistes Indépendants, Paris.

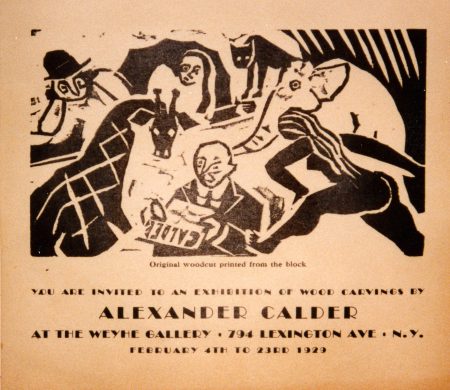

Weyhe Gallery, New York, exhibits “Wood Carvings by Alexander Calder.” Calder writes to his parents about their thoughts on the exhibition. I’m glad you think the show looked well, for I was afraid they would clutter it up and detract from things.

CF, exhibition file; CF, Calder to parents, 5 March

Sacha Stone, a German photographer, sees Calder perform Cirque Calder at the rue Cels studio. He suggests that Calder perform and exhibit in Berlin.

Calder 1966, 97The German Consulate, Paris, stamps Calder’s passport.

AAA, passportCalder leaves Paris with Stone and takes a train to Berlin to make arrangements for an exhibition.

CF, Calder to parents, 17 MarchCalder returns to Paris to gather works to exhibit in Berlin.

CF, Calder to parents, 6 April