Archive

See highlights from 1930–1936 on the timeline Shift to Abstraction

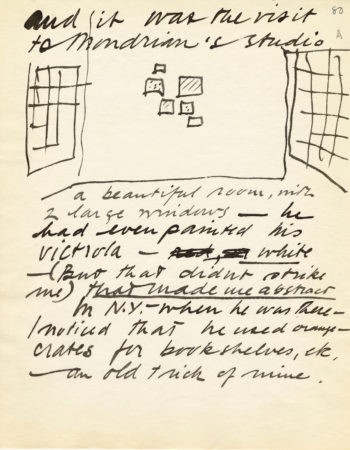

Accompanied by another American artist, William “Binks” Einstein, Calder visits Mondrian’s studio at 26 rue du Départ. Already familiar with Mondrian’s geometric abstractions, Calder is deeply impressed by the studio environment. It was a very

exciting room. Light came in from the left and from the right, and on the solid wall between the windows there were experimental stunts with colored rectangles of cardboard tacked on. Even the victrola, which had been some muddy color, was painted red. I suggested to Mondrian that perhaps it would be fun to make these rectangles oscillate. And he, with a very serious countenance, said: “No, it is not necessary, my painting is already very fast.” This one visit gave me a shock that started things. Though I had heard the word “modern” before, I did not consciously know or feel the term “abstract.” So now, at thirty-two, I wanted to paint and work in the abstract. And for two weeks or so, I painted very modest abstractions. At the end of this, I reverted to plastic work which was still abstract.

Calder exhibits nine works, including Le Lanceur de poids and Acrobate, at the “Association Artistique les Surindépendants,” Parc des Expositions, Porte de Versailles, Paris.

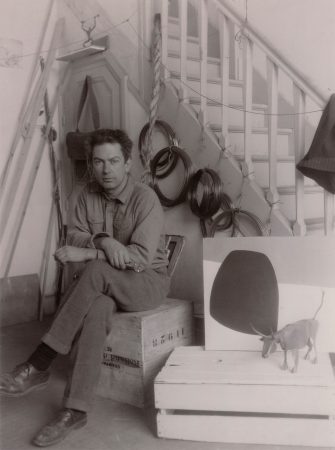

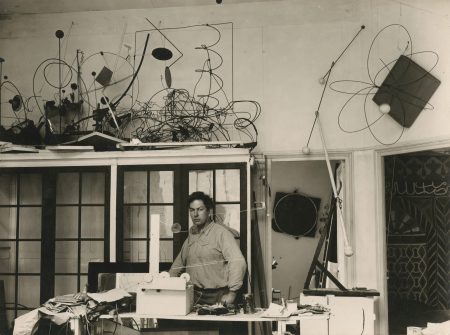

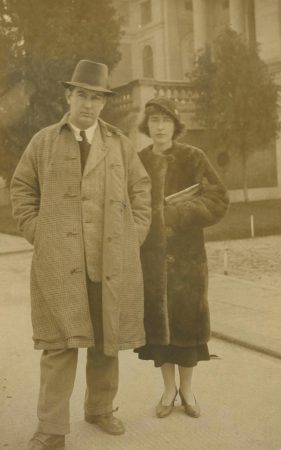

CF, exhibition fileThérèse Bonney photographs Calder in his studio at 7 Villa Brune.

NYPL, photography collection

Calder exhibits jewelry at the Mansard Gallery, London.

CF, Calder to Thomson, 5 NovemberLouisa James decides to marry Calder. I have just come home from a polo game with a not particularly entrancing young man, and I have decided that I am sick to death of going out with one person and another that don’t interest me. I am sick of it chiefly because the only

person that amuses me and has amused me for the last year and a half, is Sandy. The only thing to do to my mind is to make it permanent and get married, and the sooner the better . . . To me Sandy is a real person which seems to be a rare thing. He appreciates and enjoys the things in life that most people haven’t the sense to notice. He has ideals, ambition, and plenty of common sense, with great ability. He has tremendous originality, imagination, and humor which appeal to me very much and which make life colorful and worthwhile. He enjoys working and works hard, and thus ends the summary of his character.

Calder makes a gold ring to present to Louisa James. I had known a little jeweler in Paris, Bucci, and he had helped me make a gold ring—forerunner of an array of family jewelry—with a spiral on top and a helix for the finger. I thought this would do for a wedding ring. But Louisa

merely called this one her “engagement ring” and we had to go to Waltham, near by, and purchase a wedding ring for two dollars.

Calder exhibits four wood sculptures, including Cow, in “Painting and Sculpture by Living Americans” at the Museum of Modern Art, New York.

CF, exhibition fileCalder returns to New York on the Bremen.

Calder 1966, 114; AAA, postcard, Wiser to Calder1931

Calder prints postcards to announce performances of Cirque Calder at 903 Seventh Avenue, New York. Five performances are given; each audience includes about thirty spectators.

AAA, circus announcement; The World, 18 JanuaryCalder performs Cirque Calder at the James’s home in Concord, Massachusetts.

Calder 1966, 115Calder and Louisa James are married. The reverend who married us apologized for having missed the circus the night before. So I said: “But you are here for the circus, today.”

Calder 1966, 115

The Calders sail for Europe on the American Farmer. They return to live in Calder’s studio at 7 Villa Brune.

Hayes 1977, 249–50; Calder 1966, 116

The Abstraction-Création group is founded; members include Jean Arp, Robert Delaunay, William “Binks” Einstein, Jean Hélion, Mondrian, and Anton Pevsner.

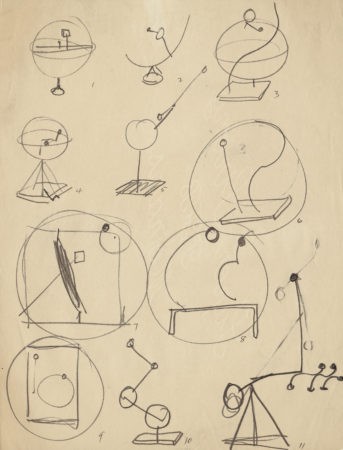

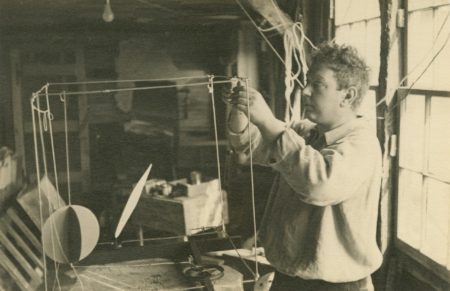

Calder 1966, 114Calder begins to incorporate movement into abstract objects. I felt that perhaps I was exactly a perfectionist: i.e. that who was I to decide that a thing should be just this way, or just that way—so I made one or 2 objects articulated, so that they could be in a number of

positions.

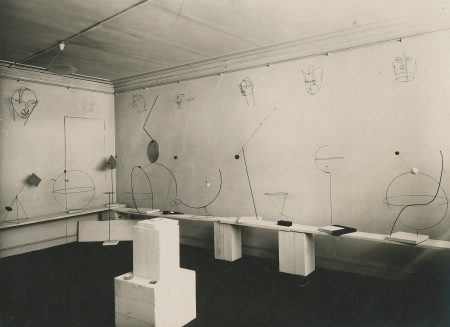

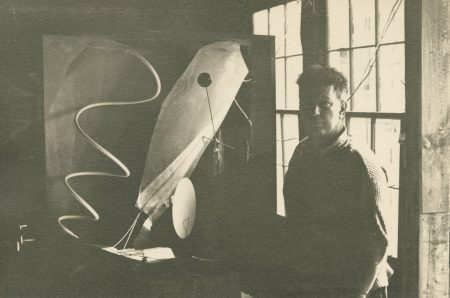

Calder’s abstract work is presented for the first time in the exhibition “Alexandre Calder: Volumes–Vecteurs–Densités / Dessins–Portraits,” at Galerie Percier, Paris. Léger writes in the introduction to the catalogue:

Eric Satie illustrated by

CALDER

Why not?

“It’s serious without seeming to be.”

Neoplastician from the start, he believed in the absolute of two colored rectangles. . . .

His need for fantasy broke the connection; he started to “play” with his materials: wood, plaster, iron, wire, especiallly iron wire. . . .a time both picturesque and spirited. . . .

. . . .A reaction; the wire stretches, becomes rigid, geometrical—pure plastic—it is the present era—an anti-Romantic impulse dominated by the problem of equilibrium.

Looking at these new works—transparent, objective, exact—I think of Satie, Mondrian, Marcel Duchamp, Brancusi, Arp—those unchallenged masters of unexpressed and silent beauty. Calder is of the same line.

He is 100% American.

Satie and Duchamp are 100% French.

And yet, we meet?

Pablo Picasso arrives before the opening at Galerie Percier to preview the exhibition privately. He introduces himself to Calder.

CF, Calder 1955–56, 95The Calders move into a three-story house at 14 rue de la Colonie. Calder makes the top floor of his house his studio.

Calder 1966, 121; Hayes 1977, 252–53; AAA, taxi receipt

Calder reinstalls the Galerie Percier exhibition in his home at 14 rue de la Colonie. I am going to set the show up again, more or less as it was in the galerie.

CF, Calder to Winston, 16 MayMary Reynolds is up from Villefranche for a few weeks, so we are seeing a bit of her and Marcel Duchamp.

CF, Calder to parents, c. 5 JuneLouisa buys a dog, a small Briard mix. She and Calder name him Feathers because of his wispy hair.

Calder 1966, 121–22; CF, Calder to parents, c. 16 June

Calder accepts an invitation to join Abstraction-Création.

Calder 1966, 114; CF, Calder to parents, 1 JulyCalder performs Cirque Calder in his studio at 14 rue de la Colonie.

CF, project fileCalder’s wire sculpture is included in an exhibition of Novembergruppe at Künstlerhaus, Berlin.

CF, exhibition fileCalder writes his parents of his new work: I have been making a few new abstractions which have certain movements combined with their other features. I think there is something in it that may be good.

CF, Calder to parents, 12 JulyThe Calders visit Palma de Mallorca, staying at the Hotel Mediterraneo. They call on the Juncosas, Pilar Miró’s family. After a month in Paguera, they return to Paris.

CF, Calder to parents, 31 July, 18 September; Calder 1966, 122–23Harrison of Paris publishes Fables of Aesop, According to Sir Roger L’Estrange, containing fifty illustrations by Calder.

CF, project fileCalder exhibits four sculptures in “Association Artistique les Surindépendants” at Parc des Expositions, Porte de Versailles, Paris.

CF, exhibition fileCalder performs Cirque Calder in his studio at 14 rue de la Colonie.

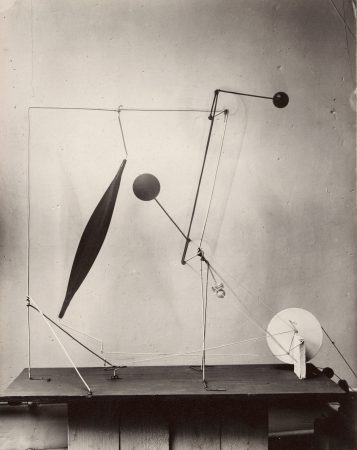

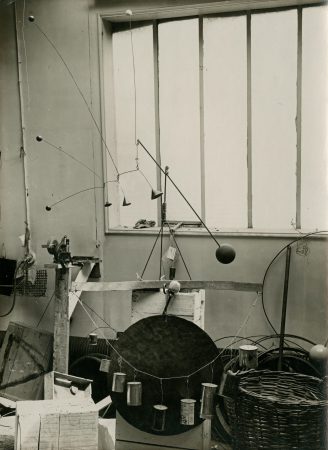

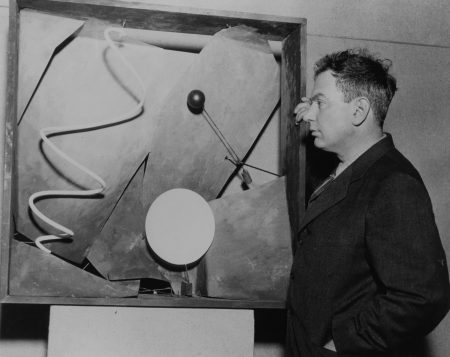

FJM, Calder to Miró, 1931Using cranks and small electric motors, Calder concentrates on making mechanized abstract sculptures.

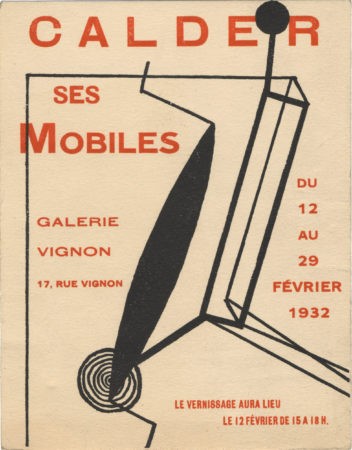

Calder 1966, 126Marcel Duchamp visits the studio at 14 rue de la Colonie again and sees Calder’s latest works. There was one motor-driven thing, with three elements. The thing had just been painted and was not quite dry yet. Marcel said, “Do you mind?” When he put his hands

on it, the object seemed to please him, so he arranged for me to show in Marie Cuttoli’s Galerie Vignon, close to the Madeleine. I asked him what sort of a name I could give these things and he at once produced “Mobile.” In addition to something that moves, in French it also means motive. Duchamp also suggested that on my invitation card I make a drawing of the motor-driven object and print: CALDER/SES MOBILES.

Calder selects a sculpture from among the works exhibited at Galerie Percier and donates it to the recently founded Miejskie Muzeum Historji i Sztuki (Muzeum Sztuki w Lodzi), in Lodz, Poland. The work is later lost during World War II. (Calder 1966, 118)

Calder 1966, 118Calder exhibits with Abstraction-Création at Porte de Versailles, Paris, and performs Cirque Calder.

CF, Calder to parents, 1 July; Lipman 1976, 331The Calders visit Port-Blanc in the Côtes-du-Nord, Brittany.

Calder 1966, 125–26; CF, Louisa to mother, 30 November1932

Calder publishes “Comment réaliser l’art?” for the first issue of Abstraction-Création, Art Non Figuratif.

Out of volumes, motion, spaces bounded by the great space, the universe.

Out of different masses, light, heavy, middling—indicated by

variations of size or color—directional line—vectors which represent speeds, velocities, accelerations, forces, etc. . . .—these directions making between them meaningful angles, and senses, together defining one big conclusion or many.

Spaces, volumes, suggested by the smallest means in contrast to their mass, or even including them, juxtaposed, pierced by vectors, crossed by speeds.

Nothing at all of this is fixed.

Each element able to move, to stir, to oscillate, to come and go in its relationships with the other elements in its universe.

It must not be just a “fleeting” moment, but a physical bond between the varying events in life.

Not extractions,

But abstractions

Abstractions that are like nothing in life except in their manner of reacting.

Calder exhibits drawings, including Untitled, in “Exposition de Dessins” at Galerie Vignon, Paris.

CF, exhibition fileCalder exhibits two works, including Untitled, in “‘1940′” at Parc des Expositions, Porte de Versailles, Paris.

CF, exhibition fileCalder makes Cadre rouge, the first in a series of “frames” and “panels” that consist of moving abstract forms set in front of colored plywood panels or within boxlike frames. The works relate to the idea of three-dimensional paintings in motion that Calder proposed to Mondrian during his 1930 visit.

Sweeney 1951, 38; CF, object files

Calder exhibits in the Fifth Annual Exhibition of Modern French Painting at the Renaissance Society at the University of Chicago.

CF, exhibition file

In response to Duchamp’s term “mobile,” Arp asks sarcastically, Well, what were those things you did last year [for Percier’s]—stabiles? Calder adopts “stabile” to refer to his static works.

Calder 1966, 130Calder performs Cirque Calder in his studio at 14 rue de la Colonie.

AAA, circus posterCalder writes the statement “Que ça bouge: À propos des sculptures mobiles.”

The various objects of the universe may be constant, at times, but their reciprocal relationships always vary.

There are environments that appear to remain fixed whilst

there are small occurrences that take place at great speed across them. They appear so only because one sees nothing but the mobility of the small occurrences.

We notice the movement of automobiles and beings in the street, but we do not notice that the earth turns. We believe that automobiles go at a great speed on a fixed ground; yet the speed of the earth’s rotation at the equator is 40,000 km every 24 hours.

As truly serious art must follow the greater laws, and not only appearances, I try to put all the elements in motion in my mobile sculptures.

It is a matter of harmonizing these movements, thus arriving at a new possibility of beauty.

In a letter to Kiesler, Calder describes the reaction to his mobiles. We had a lot of visitors—Léger, Picasso, Carl Einstein, Binks Einstein, Petro van Doesburg, Cocteau, Roux, etc.—who all were enthusiastic about “abstract sculptures which move” (toy elec. motors being

used). There was only one dissenter . . . that was Mondrian. He said they weren’t fast enough, and when I stepped on the gas, he said they still weren’t fast enough, so I said I’d make one especially fast, to please him, and then he said that that wouldn’t be fast enough—because the whole thing ought to be still. Now I feel that beauty of motion is a very real thing—unrelated to any definite machinery. Whether I’ve achieved it is, of course, another question.

Joan Miró, the Spanish painter who lives now in Barcelona, is in Monte Carlo, doing the decors for a Ballet Russe. He knows my stuff, so I wrote him, and sent him photos and perhaps I will be able to arrange for myself to do a ballet next year. The Russian who used to do them, Daglieff (?)

[sic], died 2 years ago, but one of the McCormacks has put up some money for their continuance.

In preparation for their departure from Antwerp to New York on a Belgian freighter, the Calders rent their house to Gabrielle Buffet, the former wife of Francis Picabia.

Calder 1966, 136–37Calder introduces himself in writing to American art critic James Johnson Sweeney. About 3 or 4 months [ago] M. Fernand Léger came to my house in Paris to see my “mobiles”—abstract sculptures which move—and said he would like to bring you to have a look at them too . . . I am

exposing a few of these “mobiles” at the Julien Levy Gallery 602 Madison Ave N.Y.C. and would be very pleased if you would come and see them.

“Calder: Mobiles / Abstract Sculptures” is held at the Julien Levy Gallery, New York. The exhibition announcement reprints Léger’s introduction to Calder’s 1931 Galerie Percier catalogue.

CF, exhibition file

Before a group of reporters visiting his exhibition at Julien Levy Gallery, Calder demonstrates the motion in Two Spheres. This has no utility and no meaning. It is simply beautiful. It has great emotional effect if you understand it. Of course if it meant anything it

would be easier to understand but it would not be worthwhile.

The Calders visit Louisa’s parents in Concord. Calder performs Cirque Calder at the James’ home.

CF, Calder 1955–56, 146; Concord Herald, 16 JuneWhile visiting Calder’s parents in Richmond, Massachusetts, Calder performs Cirque Calder in an old barn that Stirling uses as a studio. Invitees include Nitze, Drew, and Josephy.

CF, Calder to Nitze, 11 July; CF, Calder 1955–56, 146The Calders arrive in Barcelona after a fourteen-day passage on the Cabo Tortosa, Garcia and Díaz Spanish line. Following a stop in Málaga, they take a train from Barcelona to Tarragona.

Calder 1966, 138–40; FJM, Calder to Miró, 19 JulyThe Calders arrive at the Miró farm in Montroig for an eight- to ten-day visit. During their stay, Calder performs Cirque Calder for the Mirós, their farmhands, and their neighbors. Miró recalls the event: He came to Montroig and brought the circus figures; he never stopped working on

them. We organized a presentation for the local farmers who were very pleased with the spectacle of the wire performers. Later the Cirque was presented in galleries, but there in Montroig it was really a performance for the people.

The Calders and Mirós visit Cambrils and Tarragona.

Calder 1966, 139The Calders return to Barcelona and visit Gaudí’s basilica. Invited by the Amics de l’Art Nou, Calder performs Cirque Calder in the hall of the Grup d’Arquitects i Tecnics Catalans per al Progres de l’Arquitectura Contemporania (GATCPAC). Shortly thereafter, the Calders return to Paris.

Calder 1966, 140–41; Gasch 1932Calder performs Cirque Calder in his studio at 14 rue de la Colonie.

CF, Calder to Picasso, 10 NovemberCalder performs Cirque Calder in his studio at 14 rue de la Colonie.

CF, Calder to Picasso, 10 November1933

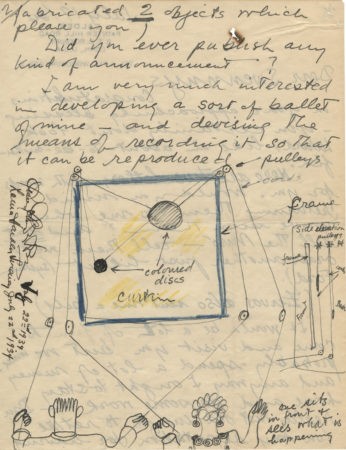

Calder publishes “Un Mobile” for the second issue of Abstraction-Création, Art Non Figuratif.

A “Mobile.”

Dimensions: 2 meters by 2 meters 50.

Frame: 8 centimeters, neutral red.

The 2 white balls turn very rapidly.

The black helix turns less rapidly and seems to always climb.

The iron plate turns still less quickly, the two black lines seeming always to climb.

The black pendulum, 40 centimeters in diameter, climbs by 45° on each side, passing in front of the frame, at the rate of 25 turns a minute

Calder’s sculptures are included in the group exhibition “Première série,” organized by the Association Artistique Abstraction-Création, Paris.

CF, exhibition fileThe Calders take a train from Paris to Madrid, where they visit the Museo del Prado.

CF, Calder to Peggy, 2 February

Works by Calder are presented at the Sociedad de Cursos y Conferencias, Residencia de Estudiantes de la Universidad de Madrid. Calder also performs Cirque Calder for the students.

AAA, circus program; CF, Louisa to mother, 11 FebruaryCalder performs Cirque Calder in Barcelona.

CF, Louisa to mother, 11 FebruaryMiró arranges for an exhibition of drawings and sculpture by Calder at the Galería Syra, Barcelona.

CF, Louisa to mother, December 1932, 11 FebruaryThe Calders travel to Rome to visit Louisa’s godmother, “Tanta” Bullard.

CF, Louisa to mother, December 1932, 11 FebruaryThe Calders return to Paris.

FJM, Calder to Miró, 15 MarchJean Painlevé films both Calder’s mechanized objects and the artist activating his works outside his studio at 14 rue de la Colonie. It is the earliest motion picture footage of mobiles in motion.

CF, project fileCalder constructs an interactive “performance” sculpture. I had a small ballet-object, built on a table with pulleys at the top of a frame. It was possible to move coloured discs across the rectangle, or fluttering pennants, or cones; to make them dance, or even

have battles between them. Some of them had large, simple, majestic movements; others were small and agitated.

Marc Vaux photographs A Merry Can Ballet in Calder’s Paris studio at 14 rue de la Colonie.

CF, photography fileCalder meets Gala and Salvador Dalí in Paris.

Calder 1966, 142Galerie Pierre Colle, Paris, exhibits “Présentation des oeuvres récentes de Calder,” including an untitled standing mobile and Small Sphere and Heavy Sphere. Reviewing the exhibition, Paul Recht writes, The liberty of some of the ensembles is absolutely

disconcerting: we see two balls, one little and one big, in turn fixed to wires of very different lengths that are themselves fixed to the two extremities of a balancing arm hung above the ground. The big ball is animated by a pendular and rotary movement; it leads the little one on unexpected evolutions that multiply by impact upon surrounding objects. They are extraordinary visual variations on the theme of calamity, by the means of gravity and centrifugal force.

Louisa has a miscarriage.

Calder 1966, 142; JJS, Calder to Sweeney, 20 September 1934“Arp, Calder, Miró, Pevsner, Hélion, and Seligmann” is presented at Galerie Pierre, Paris; Anatole Jakovski writes the text for the catalogue. At Galerie Pierre, Calder meets Sweeney, perhaps for the first time. Sweeney becomes an avid proponent of Calder’s work.

Calder 1966, 148; CF, exhibition file; Lipman 1976, 331Miró stays with the Calders at 14 rue de la Colonie while he prepares for the “Exposition surréaliste” at Galerie Pierre Colle.

Lanchner 1993, 330–31, 439Miró presents the Calders with a large blue painting as a going-away present. Calder gives him “a sort of mechanized volcano, made of ebony.”

Lanchner 1993, 330–31; CF, object file; Perls 1961

The Calders give up their house in Paris and return to New York on the SS Manhattan in the company of Hélion. There were so many articles in the European press about war preparations that we thought we had better head for home.

CF, Calder to Cooper, 2 July; Calder 1966, 143–44Upon arriving in the States, the Calders visit Louisa’s parents in Concord, Massachusetts. There, we bought a secondhand 1930 LaSalle touring car. It had a cloth top, removable, and could seat nine, with broad seats front and rear and jump seats as well. It was in good shape; I kept it a long

time and enjoyed it. You got plenty of air in this vehicle. And often I took my wares to open a show in New York in it. (All in all, I kept this LaSalle for over seventeen years!)

Louisa and Calder visit Calder’s parents in Richmond, Massachusetts. They search for a new house along the Housatonic River in Massachusetts, while also considering real estate in Tarrytown and New City, New York; Yaphank, Long Island;

and Westport and Sandy Hook, Connecticut.

Among the fifteen Calder sculptures on display in “Modern Painting and Sculpture” at the Berkshire Museum, Pittsfield, Massachusetts, are Dancing Torpedo Shape, Nymph, and one of the wire Josephine Bakers. Calder writes a

statement for the catalogue. Why not plastic forms in motion? Not a simple translatory or rotary motion but several motions of different types, speeds and amplitudes composing to make a resultant whole. Just as one can compose colors, or forms, so one can compose motions.

The Calders visit a real-estate agency in Danbury, Connecticut. After viewing several properties, they discover a dilapidated eighteenth-century farmhouse in Roxbury, Connecticut; both Louisa and Calder claim to have been the first to exclaim, “That’s it!”

Calder 1966, 143The Calders purchase the farmhouse in Roxbury. Calder converts the adjoining icehouse into a modest dirt-floored studio.

Calder 1966, 143; CF, mortgage records

The Calders stay with de Creeft in New Milford, Connecticut, during the Roxbury farmhouse renovation. By taking out a partition between a small room and the biggest one to the south—it had been a kitchen and had a sink which we removed—we turned these two rooms, exposed

east and south, with a door going directly outside, into a nice sunny living room. We made the kitchen in the north corner of the house; we like the sun but we wanted the living room to benefit from it most.

1934

Calder performs Cirque Calder at the Park Avenue home of Mr. & Mrs. Huntington Sheldon.

JJS, Calder to Sweeney, c. January 1934Calder makes Objects Oscillating Within a Cube (maquette) for the American composer Harrison Kerr.

CF, object file

The Calders attend the premiere of Virgil Thomson’s Four Saints in Three Acts, with a libretto by Gertrude Stein, which is performed at the Wadsworth Atheneum, Hartford, Connecticut. Afterward, they attend dinner at the home of A. Everett “Chick” Austin, Jr., director of the

Atheneum, where they meet with old friends, including Thomson and Julien Levy, and new acquaintances such as James Thrall Soby.

The First Municipal Art Exhibition, Radio City, Rockefeller Center, New York, exhibits three works by Calder, including a drawing titled Abstraction, and a standing mobile.

CF, exhibition file; Calder 1966, 148I thought for a moment that I was going to London last December. The Ballets Russes de Monte Carlo wired me to come to London to work on a ballet (but at my expense). They have been here for 3 months now and I am supposed to go to Monte Carlo with them when they return, but

that may fall thru, too. In the meantime I am having one of my funny expositions—at the Pierre Matisse Gallery in New York.

“Mobiles by Alexander Calder” is presented at the Pierre Matisse Gallery, New York. Sweeney writes the preface for the catalogue. The evolution of Calder’s work epitomizes the evolution of plastic art in the present century. Out of a tradition of naturalistic representation, it

has worked by a simplification of expressional means to a plastic concept which leans on the shapes of the natural world only as a source from which to abstract the elements of form.

In Roxbury, Calder creates Black Frame. One I like very much myself is a black wooden frame, with sheets of metal within it, warped into various planes, and having certain moving elements, which are the brilliant spots in an otherwise sombre setting.

CF, object file; CF, Calder to Gallatin, 13 September 1935

Massine had wired me to come to London (at my expense) last November, and in January decided to pay my fare to and from Monte Carlo, and I had decided to go (at about this time)—but as it was only to bolster up a ballet which had been very badly done sometime previous I

finally declined to have anything to do with it, preferring to wait till I was given carte blanche. It’s very annoying, for I am positive that I could do something excellent for them—but the other fellow’s ‘work’ would have been too hampering.

In Roxbury, Calder works prolifically on “panels” and “frames.”

Sweeney 1951, 38I am very much interested in developing a sort of ballet of mine—and devising the means of recording it so that it can be reproduced. The backgrounds can be changed—and the lighting varied. The discs can move anywhere within the limits of the frame, at any speed. Each disc

and its supporting pulleys is in a separate vertical plane parallel to the frame. The number of discs can be increased indefinitely—depending on the necessary clearances. In addition to discs there are coloured pennants (of cloth), with weights on them, which fly at high speed—and various solid objects, bits of hose, springs, etc. […] I had this in Paris the spring of 1933 and showed it to Massine— along with many other things, and it’s what I wanted to do for the Ballets Russes. Of course the real problem to magnify the movement to a full sized proscenium—but I can see various ways of obtaining it.

As to the ballet—I hear from Zervos that they have no cash—and can’t even put on the ballets which have been done for them. I hope to do something with Martha Graham—the American dancer—whom I saw dance this spring—and whom I think excellent.

CF, Calder to Nicholson, 28 JulyMartha Graham, the dancer, whose performances you may have seen last April in New York, and whom I consider very fine, was here last night—and we are going to try to do something together—my part being based on the idea of the ballet I worked by hand (with discs, bits of cloth,

etc.) when you came to the house in Paris.

Calder exhibits three mobile works in the Twenty-sixth Annual Stockbridge Exhibition held at the Berkshire Playhouse, Stockbridge, Massachusetts. 2 of them are for the garden, wind propelled—and (I think), good.

New York Times, 9 September; CF, Calder to Sweeney, 30 AugustCalder takes Louisa to stay with her parents in Concord during her pregnancy.

Calder 1966, 150; JJS, Calder to Sweeney, 20 September1935

“Mobiles by Alexander Calder” is held at the Renaissance Society at the University of Chicago; Sweeney writes the preface for the catalogue. On the 16th and 19th of January, Calder gives performances of Cirque Calder in the University of Chicago’s Wieboldt Hall for the Renaissance

Society. He also performs at the home of Walter S. Brewster, a trustee of the Art Institute of Chicago, on 20 January.

The Arts Club of Chicago presents “Mobiles by Alexander Calder.”

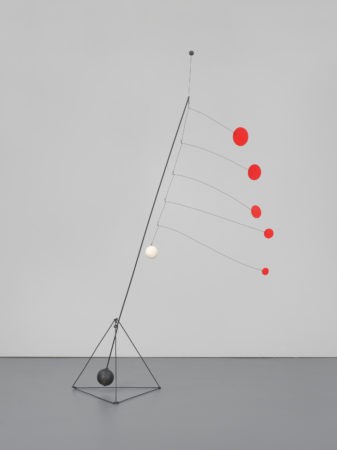

CF, exhibition fileCalder offers Sweeney a sculpture from his first show at the Pierre Matisse Gallery, for which Sweeney had written an introduction to the catalogue. Sweeney chooses Object with Red Discs; on principle, he insists that Calder accept a small sum in return for the sculpture. The

Sweeney family enjoys the object immensely and Sweeney’s brother, John, dubs it “Calderberry-bush.”

While traveling home from Chicago, Calder stops in Rochester, New York, to see Charlotte Whitney Allen, who commissions a standing mobile for her garden, which had been designed by landscape architect Fletcher Steele.

Calder 1966, 153–54

The Calders’ first daughter, Sandra, is born, on Miró’s birthday.

Calder 1966, 152

Calder constructs mobile sets for Martha Graham’s dance Panorama. On 5–6 August, Calder and Louisa visit Graham in Bennington, Vermont, to preview Panorama before its premiere at the Vermont State Armory, Bennington, on 14 August.

CF, project file