Archive

The Calders travel to Rome to visit Louisa’s godmother, “Tanta” Bullard.

CF, Louisa to mother, December 1932, 11 FebruaryThe Calders return to Paris.

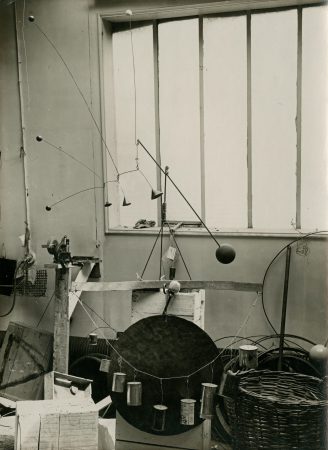

FJM, Calder to Miró, 15 MarchJean Painlevé films both Calder’s mechanized objects and the artist activating his works outside his studio at 14 rue de la Colonie. It is the earliest motion picture footage of mobiles in motion.

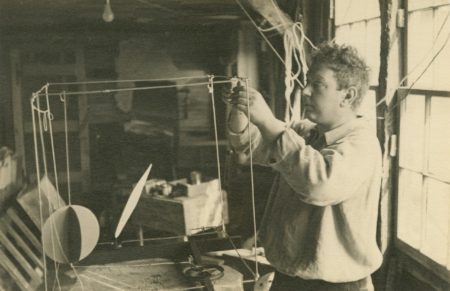

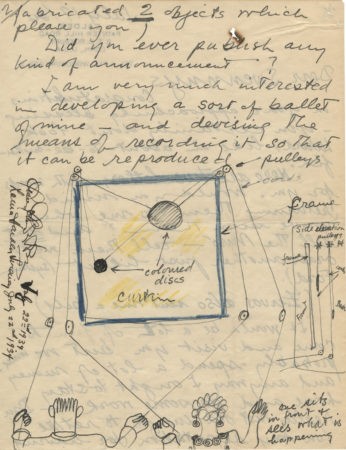

CF, project fileCalder constructs an interactive “performance” sculpture. I had a small ballet-object, built on a table with pulleys at the top of a frame. It was possible to move coloured discs across the rectangle, or fluttering pennants, or cones; to make them dance, or even

have battles between them. Some of them had large, simple, majestic movements; others were small and agitated.

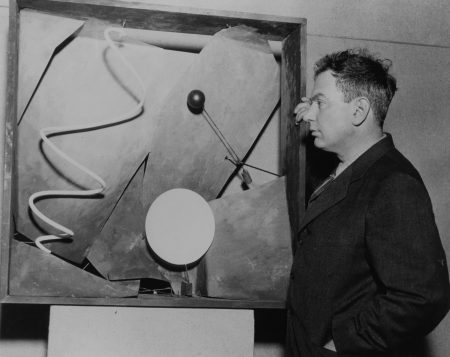

Marc Vaux photographs A Merry Can Ballet in Calder’s Paris studio at 14 rue de la Colonie.

CF, photography fileCalder meets Gala and Salvador Dalí in Paris.

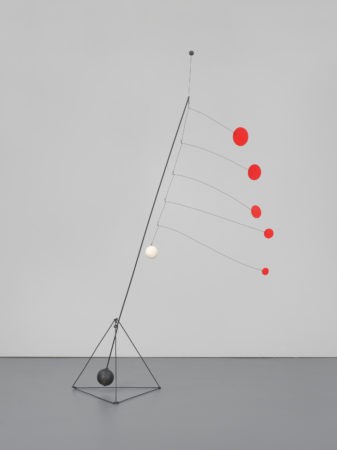

Calder 1966, 142Galerie Pierre Colle, Paris, exhibits “Présentation des oeuvres récentes de Calder,” including an untitled standing mobile and Small Sphere and Heavy Sphere. Reviewing the exhibition, Paul Recht writes, The liberty of some of the ensembles is absolutely

disconcerting: we see two balls, one little and one big, in turn fixed to wires of very different lengths that are themselves fixed to the two extremities of a balancing arm hung above the ground. The big ball is animated by a pendular and rotary movement; it leads the little one on unexpected evolutions that multiply by impact upon surrounding objects. They are extraordinary visual variations on the theme of calamity, by the means of gravity and centrifugal force.

Louisa has a miscarriage.

Calder 1966, 142; JJS, Calder to Sweeney, 20 September 1934“Arp, Calder, Miró, Pevsner, Hélion, and Seligmann” is presented at Galerie Pierre, Paris; Anatole Jakovski writes the text for the catalogue. At Galerie Pierre, Calder meets Sweeney, perhaps for the first time. Sweeney becomes an avid proponent of Calder’s work.

Calder 1966, 148; CF, exhibition file; Lipman 1976, 331Miró stays with the Calders at 14 rue de la Colonie while he prepares for the “Exposition surréaliste” at Galerie Pierre Colle.

Lanchner 1993, 330–31, 439Miró presents the Calders with a large blue painting as a going-away present. Calder gives him “a sort of mechanized volcano, made of ebony.”

Lanchner 1993, 330–31; CF, object file; Perls 1961

The Calders give up their house in Paris and return to New York on the SS Manhattan in the company of Hélion. There were so many articles in the European press about war preparations that we thought we had better head for home.

CF, Calder to Cooper, 2 July; Calder 1966, 143–44Upon arriving in the States, the Calders visit Louisa’s parents in Concord, Massachusetts. There, we bought a secondhand 1930 LaSalle touring car. It had a cloth top, removable, and could seat nine, with broad seats front and rear and jump seats as well. It was in good shape; I kept it a long

time and enjoyed it. You got plenty of air in this vehicle. And often I took my wares to open a show in New York in it. (All in all, I kept this LaSalle for over seventeen years!)

Louisa and Calder visit Calder’s parents in Richmond, Massachusetts. They search for a new house along the Housatonic River in Massachusetts, while also considering real estate in Tarrytown and New City, New York; Yaphank, Long Island;

and Westport and Sandy Hook, Connecticut.

Among the fifteen Calder sculptures on display in “Modern Painting and Sculpture” at the Berkshire Museum, Pittsfield, Massachusetts, are Dancing Torpedo Shape, Nymph, and one of the wire Josephine Bakers. Calder writes a

statement for the catalogue. Why not plastic forms in motion? Not a simple translatory or rotary motion but several motions of different types, speeds and amplitudes composing to make a resultant whole. Just as one can compose colors, or forms, so one can compose motions.

The Calders visit a real-estate agency in Danbury, Connecticut. After viewing several properties, they discover a dilapidated eighteenth-century farmhouse in Roxbury, Connecticut; both Louisa and Calder claim to have been the first to exclaim, “That’s it!”

Calder 1966, 143The Calders purchase the farmhouse in Roxbury. Calder converts the adjoining icehouse into a modest dirt-floored studio.

Calder 1966, 143; CF, mortgage records

The Calders stay with de Creeft in New Milford, Connecticut, during the Roxbury farmhouse renovation. By taking out a partition between a small room and the biggest one to the south—it had been a kitchen and had a sink which we removed—we turned these two rooms, exposed

east and south, with a door going directly outside, into a nice sunny living room. We made the kitchen in the north corner of the house; we like the sun but we wanted the living room to benefit from it most.

1934

Calder performs Cirque Calder at the Park Avenue home of Mr. & Mrs. Huntington Sheldon.

JJS, Calder to Sweeney, c. January 1934Calder makes Objects Oscillating Within a Cube (maquette) for the American composer Harrison Kerr.

CF, object file

The Calders attend the premiere of Virgil Thomson’s Four Saints in Three Acts, with a libretto by Gertrude Stein, which is performed at the Wadsworth Atheneum, Hartford, Connecticut. Afterward, they attend dinner at the home of A. Everett “Chick” Austin, Jr., director of the

Atheneum, where they meet with old friends, including Thomson and Julien Levy, and new acquaintances such as James Thrall Soby.

The First Municipal Art Exhibition, Radio City, Rockefeller Center, New York, exhibits three works by Calder, including a drawing titled Abstraction, and a standing mobile.

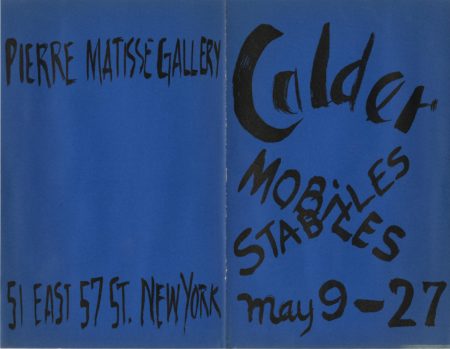

CF, exhibition file; Calder 1966, 148I thought for a moment that I was going to London last December. The Ballets Russes de Monte Carlo wired me to come to London to work on a ballet (but at my expense). They have been here for 3 months now and I am supposed to go to Monte Carlo with them when they return, but

that may fall thru, too. In the meantime I am having one of my funny expositions—at the Pierre Matisse Gallery in New York.

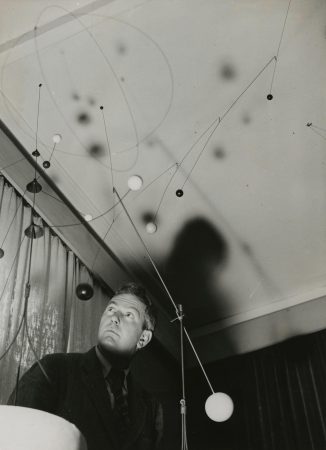

“Mobiles by Alexander Calder” is presented at the Pierre Matisse Gallery, New York. Sweeney writes the preface for the catalogue. The evolution of Calder’s work epitomizes the evolution of plastic art in the present century. Out of a tradition of naturalistic representation, it

has worked by a simplification of expressional means to a plastic concept which leans on the shapes of the natural world only as a source from which to abstract the elements of form.

In Roxbury, Calder creates Black Frame. One I like very much myself is a black wooden frame, with sheets of metal within it, warped into various planes, and having certain moving elements, which are the brilliant spots in an otherwise sombre setting.

CF, object file; CF, Calder to Gallatin, 13 September 1935

Massine had wired me to come to London (at my expense) last November, and in January decided to pay my fare to and from Monte Carlo, and I had decided to go (at about this time)—but as it was only to bolster up a ballet which had been very badly done sometime previous I

finally declined to have anything to do with it, preferring to wait till I was given carte blanche. It’s very annoying, for I am positive that I could do something excellent for them—but the other fellow’s ‘work’ would have been too hampering.

In Roxbury, Calder works prolifically on “panels” and “frames.”

Sweeney 1951, 38I am very much interested in developing a sort of ballet of mine—and devising the means of recording it so that it can be reproduced. The backgrounds can be changed—and the lighting varied. The discs can move anywhere within the limits of the frame, at any speed. Each disc

and its supporting pulleys is in a separate vertical plane parallel to the frame. The number of discs can be increased indefinitely—depending on the necessary clearances. In addition to discs there are coloured pennants (of cloth), with weights on them, which fly at high speed—and various solid objects, bits of hose, springs, etc. […] I had this in Paris the spring of 1933 and showed it to Massine— along with many other things, and it’s what I wanted to do for the Ballets Russes. Of course the real problem to magnify the movement to a full sized proscenium—but I can see various ways of obtaining it.

As to the ballet—I hear from Zervos that they have no cash—and can’t even put on the ballets which have been done for them. I hope to do something with Martha Graham—the American dancer—whom I saw dance this spring—and whom I think excellent.

CF, Calder to Nicholson, 28 JulyMartha Graham, the dancer, whose performances you may have seen last April in New York, and whom I consider very fine, was here last night—and we are going to try to do something together—my part being based on the idea of the ballet I worked by hand (with discs, bits of cloth,

etc.) when you came to the house in Paris.

Calder exhibits three mobile works in the Twenty-sixth Annual Stockbridge Exhibition held at the Berkshire Playhouse, Stockbridge, Massachusetts. 2 of them are for the garden, wind propelled—and (I think), good.

New York Times, 9 September; CF, Calder to Sweeney, 30 AugustCalder takes Louisa to stay with her parents in Concord during her pregnancy.

Calder 1966, 150; JJS, Calder to Sweeney, 20 September1935

“Mobiles by Alexander Calder” is held at the Renaissance Society at the University of Chicago; Sweeney writes the preface for the catalogue. On the 16th and 19th of January, Calder gives performances of Cirque Calder in the University of Chicago’s Wieboldt Hall for the Renaissance

Society. He also performs at the home of Walter S. Brewster, a trustee of the Art Institute of Chicago, on 20 January.

The Arts Club of Chicago presents “Mobiles by Alexander Calder.”

CF, exhibition fileCalder offers Sweeney a sculpture from his first show at the Pierre Matisse Gallery, for which Sweeney had written an introduction to the catalogue. Sweeney chooses Object with Red Discs; on principle, he insists that Calder accept a small sum in return for the sculpture. The

Sweeney family enjoys the object immensely and Sweeney’s brother, John, dubs it “Calderberry-bush.”

While traveling home from Chicago, Calder stops in Rochester, New York, to see Charlotte Whitney Allen, who commissions a standing mobile for her garden, which had been designed by landscape architect Fletcher Steele.

Calder 1966, 153–54The Calders’ first daughter, Sandra, is born, on Miró’s birthday.

Calder 1966, 152

Calder constructs mobile sets for Martha Graham’s dance Panorama. On 5–6 August, Calder and Louisa visit Graham in Bennington, Vermont, to preview Panorama before its premiere at the Vermont State Armory, Bennington, on 14 August.

CF, project fileCalder presents Bonnie Bird, one of the lead dancers of Panorama, a brooch in the shape of a bird.

Bell-Kanner 1998, 80Calder and Louisa visit Charlotte Whitney Allen in Rochester, New York. While there, Calder constructs the large standing mobile she had commissioned for her garden and he gives a performance of Cirque Calder.

CF, Calder to Allen, 24 SeptemberThe Calders spend the winter in an apartment at 244 East Eighty-sixth Street and Second Avenue, New York. Calder rents a small store and converts it into a studio.

Calder 1966, 156; Calder to Thomson, April 1936

Thomas H. Fisher, husband of choreographer Ruth Page, writes to Calder: Ruth [Page] and I have the novel idea that you should construct for her a large scale ‘mobile’ to be used alone on the stage, with music and lights between her ballets. The idea would be to enlarge such a

mobile as the one I saw in the Museum of Modern Art to stage proportions using different colored objects in motion and then playing lights on the mobile from the wings and elsewhere in the theatre. The music would, perhaps, be something like Varese or something else which would be suitable to the particular mobile being displayed.

Calder again collaborates with Graham, making a group of six mobiles—”visual preludes”—for her dance Horizons.

CF, project file; "Martha Graham and Dance Group," 193624 December: The large ‘overhead’ mobile should be in its box in your basement (awaiting my pleasure). Do you think you would care to put it up anywhere during la semaine folle—only a suggestive question—because Ruth Page wishes me to do an object which she can use, here,

and in Chicago, to pinch-hit for one of her solo dances—and I thought of that one.

1936

Page writes to Calder: I have been experimenting with my brass mobile which you sent here and have decided that it is much more beautiful without me than with me. Any movements of mine just spoil it. However, we tried it just in the room here with lights and music and it is a thrilling dance all

by itself and we would have to produce it just by itself with lights and music. Blow an electric fan on it so that it moves very slightly. But it seems to me there should be a little group of 2 or 3 to make an impression—like 3 short dances.

George Platt Lynes photographs Calder.

CF, photography file“Mobiles and Objects by Alexander Calder” is held at the Pierre Matisse Gallery, New York.

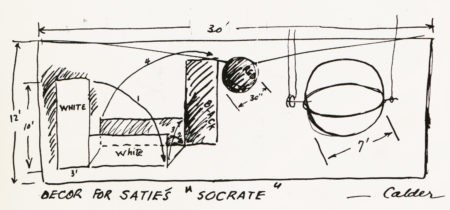

CF, exhibition fileFirst Hartford Music Festival, Wadsworth Atheneum, presents Erik Satie’s symphonic drama Socrate. Virgil Thomson and A. Everett “Chick” Austin, Jr., have commissioned Calder to create the mobile decor for the performance. As the singers stand still at either end of the

stage, Calder’s simple geometric objects in space enact a series of movements. Later that night the festival continues with Paper Ball: Le Cirque des Chiffoniers, designed by Pavel Tchelitchew and featuring thirteen processions of paper costumes created especially for the event. For Soby’s procession, Calder contributes A Nightmare Side Show, a suite of animal costumes designed to wear over evening clothes.

Graham premieres Horizons at the Guild Theatre in New York City. The program note reads: The “Mobiles,” designed by Alexander Calder, are a new conscious use of space. They are employed in Horizons as visual preludes to the dances in this suite. The dances do not interpret the “Mobiles,” nor

do the “Mobiles” interpret the dances. They are employed to enlarge the sense of horizon.

“Cubism and Abstract Art” is presented by Alfred H. Barr, Jr., at the Museum of Modern Art, New York. Calder is represented by three works: Objet Volant, a large mobile commissioned to hang on the flagpole outside the museum, announcing the show; A Universe; and a mobile.

CF, exhibition file

Calder performs Cirque Calder in New York at the Pierre Matisse Gallery.

AAA, Calder to Bunce, 26 MarchErik Satie’s Socrate with Calder’s mobile decor is performed at the Colorado Springs Fine Arts Center.

CF, project file

Galerie Charles Ratton, Paris, presents “Exposition surréaliste d’objets.” Calder contributes a mobile.

CF, exhibition file

Roland Penrose’s “International Surrealist Exhibition” at his New Burlington Galleries, London, includes two sculptures by Calder, among them Requin et Baleine. André Breton writes the preface to the catalogue.

CF, exhibition fileThe Calders vacation at Eastham on Cape Cod.

AAA, Calder to Bunce, 13 JulyJulien Levy’s Surrealism, the first English text on the subject, is published in New York. Levy writes: It is impossible accurately to estimate the relative importance of the younger surrealists, until aided by the perspective of time. Outstanding among the newcomers seem to

be Gisèle Prassinos, Richard Oelze, Hans Bellmer, Leonor Fini, Alexander Calder, and Joseph Cornell . . . Calder is sometimes surrealist and sometimes abstractionist. It is to be hoped that he may soon choose in which direction he will throw the weight of his talents.

Calder is commissioned by architect Paul Nelson to design a trophy for CBS’s Annual Amateur Radio Award. The work is William S. Paley Trophy for Amateur Radio.

CF, project file; Calder 1966, 155Calder’s Praying Mantis and Object with Yellow Background are included in the exhibition “Fantastic Art, Dada, Surrealism,” organized by the Museum of Modern Art, New York.

CF, exhibition fileCalder performs Cirque Calder in his apartment at 244 East Eighty-sixth Street and Second Avenue, New York.

AAA, Calder to Bunce, 9 December1937

Calder designs scenery and costumes for OO to AH, a playlet in two scenes written by Charles Tracy but never performed.

CF, project file; Tracy 1937Calder’s first large-scale bolted stabiles, Devil Fish and Big Bird, are on view in “Calder: Stabiles & Mobiles” at the Pierre Matisse Gallery, New York.

CF, exhibition file

The Calders obtain visas in New York in preparation for their voyage to Europe.

CF, passportThe Calders depart on the SS Lafayette for Le Havre, France. Their daughter Sandra, aged two, and her caretaker Dorothy Sibley join them.

Calder 1966, 156; CF, travel fileThe Calders arrive in Le Havre, France.

CF, passport; Calder 1966, 156Nelson and his wife, Francine, invite the Calders to stay with them in Varengeville, on the Normandy coast. Léger, Pierre Matisse, and Matisse’s wife, Teeny, also visit.

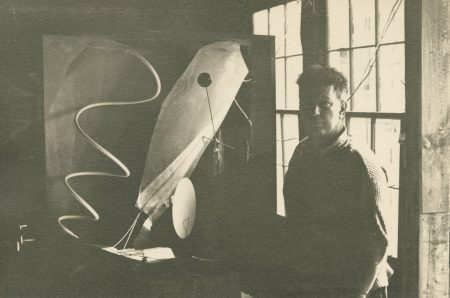

Calder 1966, 156–57The Calders return to Paris, where they move to 80 boulevard Arago, a house designed by Nelson and owned by Calder’s friend Alden Brooks. Visitors include Finnish architect Alvar Aalto and his wife, Aino. Calder uses the garage, outfitted with an automotive turntable, as a studio.

Calder 1966, 157–58Calder and Miró visit the Spanish pavilion under construction at the 1937 World’s Fair site in Paris. Calder meets the pavilion’s architects, Josep Lluís Sert and Luis Lacasa. Sert eventually commissions Calder to make Mercury Fountain for the Spanish pavilion. Mined in Almadén in

Spain, the mercury symbolizes Republican resistance to fascism.

Honolulu Academy of Arts, Hawaii, presents “Fantastic Art: Miró and Calder.”

CF, exhibition fileCalder performs Cirque Calder at 80 boulevard Arago, Paris.

Bruguière Collection, Paris, circus invitationThe Calders rent a house in Varengeville at 50 le Clos du Timbre, where Calder uses the garage as his studio. Jean Hélion, who had been to London a few years before, had put me in contact with John and Myfanwy Piper and Ben Nicholson and Barbara Hepworth, and we lost no

time in inviting the Pipers and the Nicholsons, separately, of course. Other visitors to the house include Georges Braque, Pierre Loeb, Miró, the Nelsons, and cultural theorist Herbert Read.

The Spanish pavilion, featuring Picasso’s Guernica, Miró’s Le Faucheur, and Calder’s Mercury Fountain, opens at the Paris World’s Fair.

CF, exhibition file

The Calders arrive in Folkstone, England, later renting an apartment at Belsize Park, London. Calder establishes a studio in Camden Town and gives Cirque Calder performances.

CF, passport; Calder 1966, 164–65While in London, Calder makes his first gold necklace for Louisa.

CF, Calder to Warner, 16 December 1946The Mayor Gallery, London, exhibits “Calder: Mobiles and Stabiles.”

CF, exhibition file

A review of the exhibition at the Mayor Gallery notes, Calder’s jewelry is as pretty as his mobiles—some of it too is “mobile”—and often more seriously lovely. If the lady of fashion has the wit to see it, she may find that pieces of human ingenuity make rather more distinguished ornaments

than Cartier’s portable currency.

In reference to the Mayor Gallery exhibition, Calder writes, The show is going quite well . . . Sold 3 objects so far, + a lot of jewelry. Buyers of his jewelry include prominent characters of London society, including Lady Clark, wife of London’s National Gallery director, Kenneth Clark.

CF, Calder to Sweeney, 14 December; CF, exhibition file, unsigned newspaper clipping from Sketch, 8 DecemberAn unsigned review of the Mayor Gallery in Vogue declares, Calder . . . occasionally makes jewellery of great charm and originality. He bends and twists gold and silver metal into fantastic and gorgeous patterns, very much in the modern manner. Women of taste should ask to see some at the

Gallery.

1938

The Calders return to New York. They rent a different apartment in the building at 244 East Eighty-sixth Street and Second Avenue where they had previously lived.

Calder 1966, 167Calder begins construction of a large studio on the old dairy barn foundations in Roxbury. Soon after, he converts his icehouse studio into a living space that comes to be known as the “Big Room.”

Calder 1966, 169–70

Calder’s first retrospective, “Calder Mobiles,” is presented by the George Walter Vincent Smith Gallery, Springfield, Massachusetts. Sweeney writes a foreword to the catalogue. Aalto, Léger, architectural historian Siegfried Giedion, and art patron Katherine S. Dreier attend the

opening. Sixty-one pieces of jewelry are included in the exhibition.

Artek Gallery, Helsinki, presents “Alexander Calder: Jewelry.”

CF, exhibition file1939

Calder is commissioned by the Museum of Modern Art, New York, to make Lobster Trap and Fish Tail, a mobile he installs in the principal stairwell of the museum’s new building on West Fifty-third Street.

Lipman 1976, 332; Marter 1991, 197

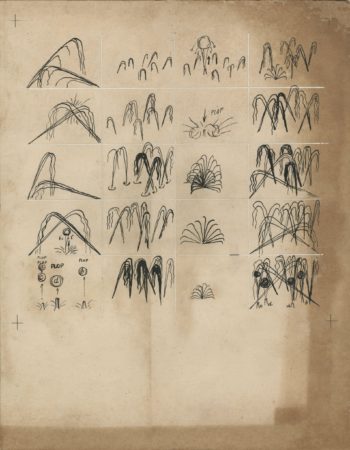

Calder is invited to make sculptures for an African habitat designed by Oscar Nitzschke for the Bronx Zoo. Calder conceives of treelike sculptures to be made in steel so they can withstand the abuse of the wild animals. Although the habitat is never realized, Calder creates five

models for the project: Sphere Pierced by Cylinders, Hollow Egg, Four Leaves and Three Petals, Leaves and Tripod, and The Hairpins.

Calder creates six maquettes to complement architect Percival Goodman’s design for the Smithsonian Gallery of Art Architectural Competition, sponsored by the Smithsonian Gallery of Art Commission. Goodman is awarded second place to Eliel Saarinen, and the

project goes unrealized.

The exhibition “III Salão de Maio,” São Paulo, Brazil, includes gouaches and a mobile by Calder.

CF, exhibition fileCalder is commissioned by Wallace K. Harrison and André Fouilhoux, architects of Consolidated Edison’s pavilion at the 1939 New York World’s Fair, to design a “water ballet” for the building’s fountain. Although water jets are installed around the pavilion, this ballet is never

executed.

Calder submits a Plexiglas stabile to a competition sponsored by Röhm and Haas at the Museum of Modern Art, New York. The work is exhibited at the Hall of Industrial Science during the New York World’s Fair.

CF, exhibition file; Calder 1966, 175; "Abstract Sculpture in Plexiglas," 1939“Calder Mobiles–Stabiles” is on view at the Pierre Matisse Gallery, New York.

CF, exhibition file

The Calders’ second daughter, Mary, is born.

Calder 1966, 174

Sert and his wife, Moncha, pay an extended visit to the Calders in Roxbury.

Calder 1966, 1741940

Marian Willard shows an array of Calder’s jewelry to Valentina, a renowned haute couture dressmaker in New York. Valentina objects to the prices of the items and Willard takes them next to Harper’s Bazaar where they are photographed.

CF, Willard to Calder, 9 OctoberA private exhibition of Calder’s sculptures takes place inside and outside the home of Wallace Harrison and his wife, Ellen, in Huntington, Long Island.

MoMA, invitation; CF, Myra Martin to Ellen Harrison, 24 OctoberCarmel Snow, the legendary editor of Harper’s Bazaar, writes to Willard: The photographs of Sandy Calder’s jewelry turned out beautifully . . . we will publish these either in December or January.

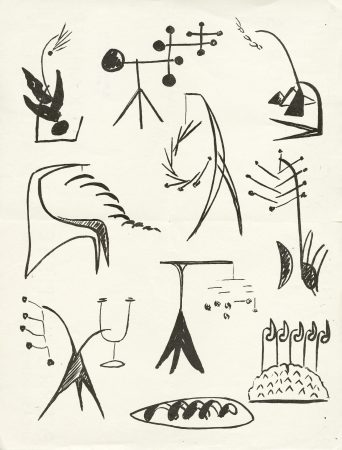

CF, Snow to Willard, 16 October“Calder Jewelry” is presented at Willard Gallery, New York. In her press release for the show, Willard writes, These works of art are savage and deliberate and self-confidently sophisticated . . . This is a master modern artist’s contribution to the history of fashion. For a world already in

chains it is superb stuff.

1941

Harrison commissions Calder to make a mobile for the Hotel Avila Ballroom, Caracas, Venezuela.

CF, project file

“Alexander Calder: Mobiles / Jewelry” and “Fernand Léger: Gouaches / Drawings” are presented at the Arts and Crafts Club of New Orleans. Twenty-five works of jewelry are exhibited.

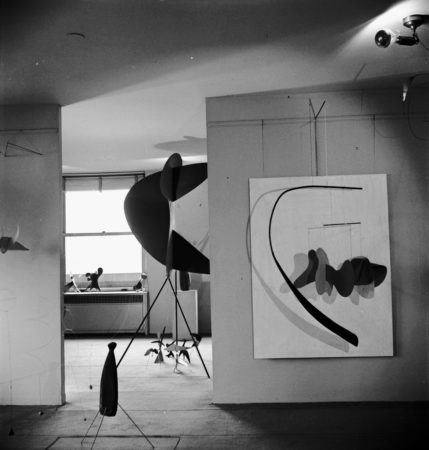

CF, exhibition fileHerbert Matter photographs Calder’s Roxbury studio.

CF, photography file

“Alexander Calder: Recent Works” is held at the Pierre Matisse Gallery, New York.

CF, exhibition file

Calder performs Cirque Calder in Roxbury.

CF, object file