Alexander Calder created works of art throughout his childhood. While living in Pasadena in 1906 amidst the flourishing Arts and Crafts Movement, Calder was given his first tools and a workshop where he made toys and jewelry for his sister’s dolls. For Christmas in 1909, Calder presented his parents with two of his earliest sculptures, a dog and a duck made out of bent brass sheet. In his twenties, Calder moved to New York and studied at the Art Students League where he produced paintings congruous with the Ashcan aesthetic. He worked concurrently at the National Police Gazette, illustrating sporting events and the Ringling Bros. and Barnum & Bailey Circus, and he made hundreds of brush drawings of animals at the Bronx and Central Park zoos, later published in Animal Sketching. Calder commonly used sheet metal and wire for sculptures and other projects during this period.

Calder is born in Philadelphia to Nanette Lederer Calder, a painter, and Alexander Stirling Calder, a sculptor.

I always thought I was born—at least my mother always told me so—on August 22, 1898. But my grandfather Milne’s birthday was on August 23, so there might have been a little confusion. In 1942, when I wrote the Philadelphia City Hall for a birth certificate, I sent them a dollar and they told me I was born on the twenty second of July, 1898. So I sent them another dollar and told them, “Look again.” They corroborated the first statement.

Calder poses for his father’s sculpture, Man Cub, in Philadelphia. Calder sculpts his own clay elephant.

Calder poses for his father’s sculpture, Man Cub, in Philadelphia. Calder sculpts his own clay elephant.

Stirling Calder contracts tuberculosis. Calder’s parents move to a ranch in Oracle, Arizona, leaving Calder and his sister Peggy in the care of Dr. Charles P. Shoemaker, a dentist, and his wife, Nan.

Nanette picks up Calder and Peggy and they rejoin their father in Oracle. Calder befriends Riley, an elderly man recuperating at the ranch who shows him “how to make a wigwam out of burlap bags pinned together with nails.”

The Calders move to Pasadena, California.

At that time, on Euclid Avenue in Pasadena, I got my first tools and was given the cellar with its window as a workshop. Mother and father were all for my efforts to build things myself—they approved of the homemade . . . My workshop became some sort of a center of attraction; everybody came in.

Peggy once gave me a very nice pair of pliers at Christmas. I made her a little Christmas tree, completely decorated, out of a fallen branch. So she wept because my gift was homemade.

The Calders move to Croton-on-Hudson, New York. Calder has a cellar for his workshop and attends Croton Public School.

For Christmas, Calder presents his parents with a dog and a duck that he trimmed from a brass sheet and bent into formation. The duck is kinetic, rocking back and forth when tapped.

For his father’s birthday, Calder makes Animal Zoo Puzzle, a game consisting of five painted animals—a tiger, a lion, and three bears—and a wooden board with nails divided into six pens. The challenge is to move the animals from their pens without having two animals in the same pen at once.

Stirling is appointed as the acting chief of the department of sculpture of the Panama-Pacific International Exposition in San Francisco. He writes the introduction to The Sculpture and Mural Decorations of the Exposition, published in 1915.

The Calders move to San Francisco. Calder has a workshop in the cellar and attends Lowell High School.

Calder begins his studies at Stevens Institute of Technology, Hoboken, New Jersey, where he takes courses that include chemistry, mechanical drawing, shop practice, and surveying, among others.

Calder graduates from Stevens with a degree in mechanical engineering.

Serving on the H.F. Alexander as a fireman in the boiler room, Calder sails from New York to San Francisco via the Panama Canal.

It was early one morning on a calm sea, off Guatemala, when over my couch—a coil of rope—I saw the beginning of a fiery red sunrise on one side and the moon looking like a silver coin on the other. Of the whole trip this impressed me most of all; it left me with a lasting sensation of the solar system.

Arriving in San Francisco, Calder takes a lumber schooner to Willapa Harbor, Washington, where he catches the bus for Aberdeen and meets his sister Peggy and her husband, Kenneth Hayes. Calder finds a job as a timekeeper for a logging camp in Independence, Washington.

I was supposed to make out paychecks for people. I also had to scale the logs as they were loaded on the flatcars.

Inspired by the logging camp landscape, Calder writes home and asks his mother for paints and brushes.

With the help of Stirling’s introduction, Calder seeks employment with an engineer in Canada.

I went to Vancouver and called on him, and we had quite a talk about what career I should follow. He advised me to do what I really wanted to do—he himself often wished he had been an architect. So, I decided to become a painter.

Calder begins classes at the Art Students League of New York, studying life and pictorial composition with John Sloan and portrait painting with George Luks.

Calder begins his first job as an artist, illustrating sporting events and city scenes for the National Police Gazette.

A total eclipse of the sun is visible from the northern part of Manhattan. Along with thousands of New Yorkers, Calder travels uptown, stopping at the steps of Columbia University to watch. He makes The Eclipse, an oil painting of the scene.

Calder makes hundreds of brush drawings of animals at the Bronx Zoo and the Central Park Zoo.

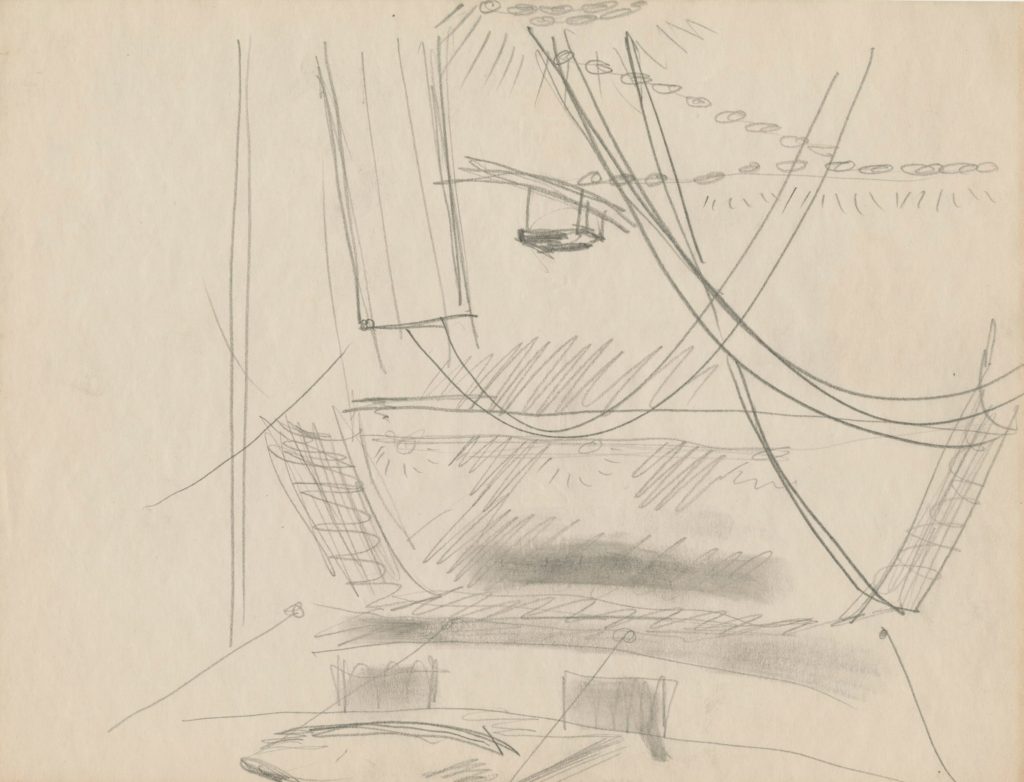

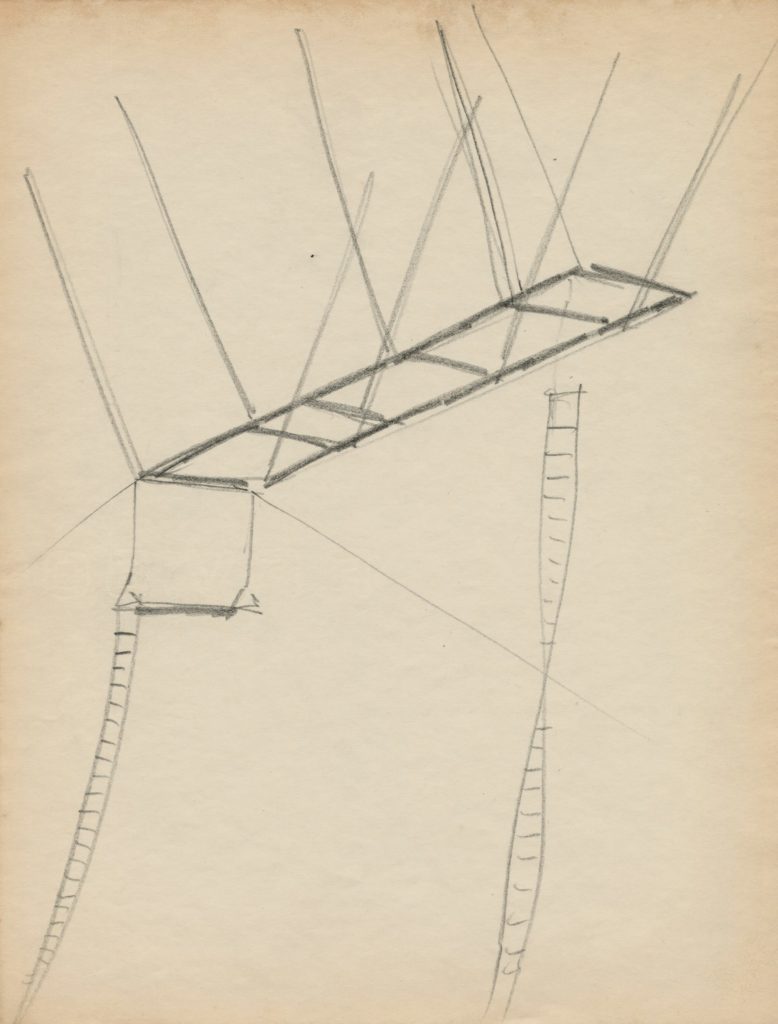

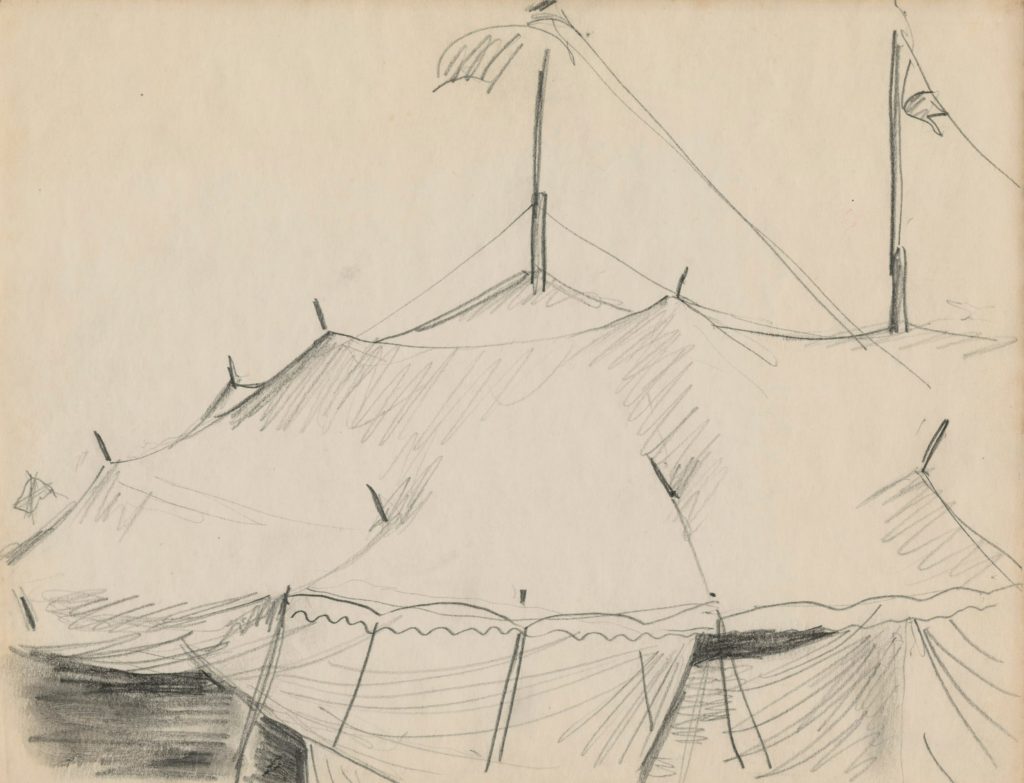

Calder travels to Florida. First he visits Miami, then Sarasota, where he sketches at the winter grounds of the Ringling Bros. and Barnum & Bailey Circus. I was very fond of the spatial relations. I love the space of the circus. I made some drawings of nothing but the tent. The whole

thing of the—the vast space—I’ve always loved it.

Soon after moving to Paris in 1926, Calder created his Cirque Calder. Made of wire and a spectrum of found materials, the Cirque was a work of performance art that gained Calder an introduction to the Parisian avant-garde. He continued to explore his invention of wire sculpture, whereby he “drew” with wire in three dimensions the portraits of friends, animals, circus themes, and personalities of the day.