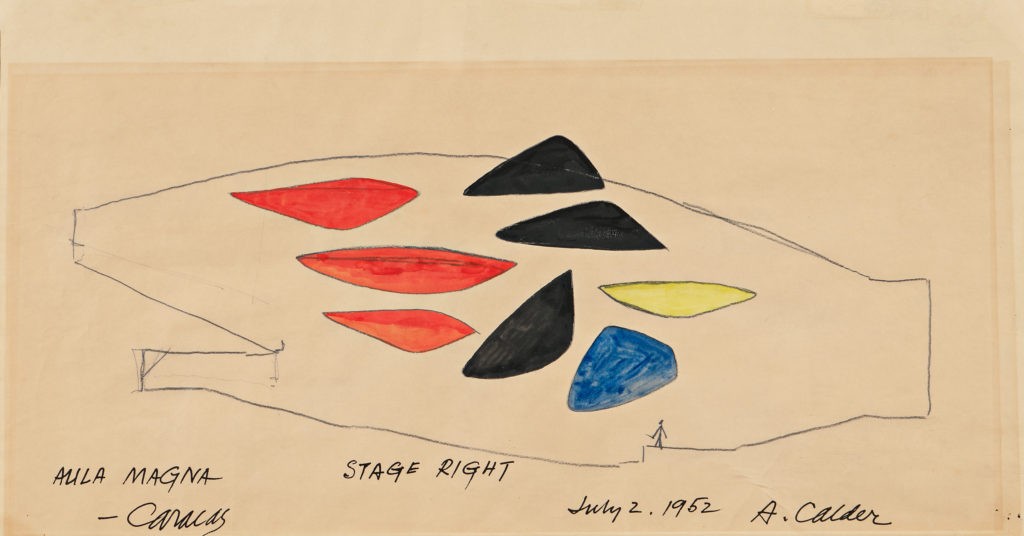

Eager to exhibit again in Europe after the end of World War II, Calder had a major show in 1946 at Galerie Louis Carré in Paris for which Jean-Paul Sartre wrote a seminal essay. Calder traveled to Brazil in 1948 where he held two highly successful exhibitions in Rio de Janeiro and São Paulo. International Mobile, made in 1949 for the Philadelphia Museum of Art’s Third International Exhibition of Sculpture, was Calder’s largest mobile to date. He designed sets and costumes for a number of theatrical performances and accepted a grand commission to design a huge acoustic ceiling for the Aula Magna auditorium at Universidad Central de Venezuela. In 1952, Calder represented the United States at the Venice Biennale, winning the grand prize for sculpture.

When Sartre visits Calder again at his studio in New York, the artist gives him Peacock, a mobile whose elements are cut from flattened 1940 Connecticut license plates.

Calder takes his first transatlantic flight from New York to Paris to prepare for the exhibition at Galerie Louis Carré, Paris.

Calder’s jewelry is included in the large group exhibition “Modern Jewelry Design” at the Museum of Modern Art, New York. Over the next two years, the show travels to museums in fifteen different cities throughout the United States.

“4 Modern Sculptors: Brancusi, Calder, Lipchitz, Moore” is presented at the Cincinnati Modern Art Society.

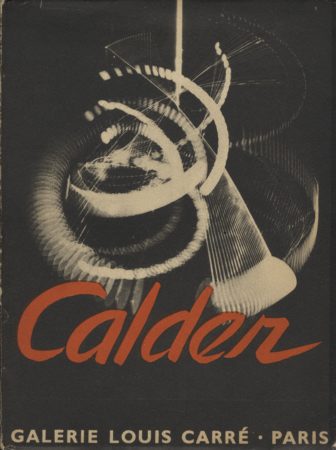

“Alexander Calder: Mobiles, Stabiles, Constellations” is on view at Galerie Louis Carré, Paris. Henri Matisse attends the exhibition. Along with photographs by Matter, the catalogue includes two essays—Sartre’s “Les Mobiles de Calder” and Sweeney’s “Alexander

Calder.”

Jean-Paul Sartre, Les Mobiles de Calder

Galerie Louis Carré, Paris. Alexander Calder: Mobiles, Stabiles, Constellations. Exhibition catalogue. 1946.

Sculpture suggests movement, painting suggests depth or light. Calder suggests nothing. He captures true, living movements and crafts them into something. His mobiles signify nothing, refer to nothing other than themselves. They simply are: they are absolutes. Read more

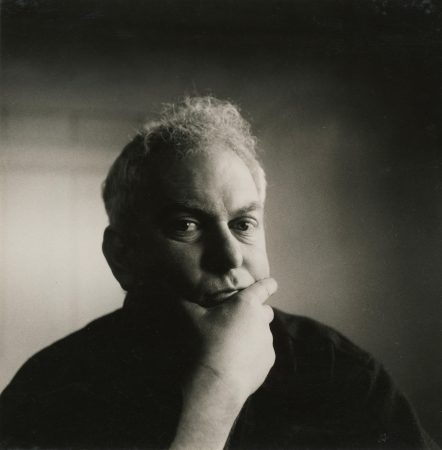

Irving Penn photographs Calder in Roxbury.

Miró celebrates his and Sandra’s birthday with the Calders at their apartment on East Seventy-second Street, New York. He gives Sandra a drawing and she gives the Mirós an ink and collage butterfly. Calder presents Miró with a mobile personage made of animal bones.

Kunsthalle Bern, Switzerland, presents “Calder, Léger, Bodmer, Leuppi.”

Calder trades the mobile Polygones noirs for Miró’s Femmes et oiseaux dans la nuit, a painting related to Miró’s mural for the Terrace Plaza Hotel.

Calder exhibits Explosive Object in the “Exposition de peintures et sculptures contemporaines,” Palais des Papes, Avignon.

Carl Van Vechten photographs Calder.

Calder rebuilds the “Big Room” in his Roxbury house. We are rebuilding the room which burned four years ago (where we sat last time you were here). Over the next year, Calder raises the roof about five feet and installs steel sash windows in the southeast wall.

“Alexander Calder” is on view at Buchholz Gallery/Curt Valentin, New York.

Calder’s daughter Mary has a painful molar extracted on Christmas Day. Calder takes the tooth and memorializes it in a silver wire, caged pendant, which he gives to her for Christmas.

Hans Richter’s film, Dreams That Money Can Buy, is finally released after being in production since 1945. Two sequences are made with Calder’s collaboration: “Ballet,” the fifth dream, and “Circus,” the sixth dream. The film wins the International Award for Best Original Contribution to the

Progress of Cinematography at the Venice Film Festival.

Calder and Louisa arrive in Rio de Janeiro.

The Ministerio da Educaçao e Saude presents “Alexander Calder.” The catalogue includes “Les Mobiles de Calder” by Sartre, “Alexander Calder” by Mindlin, and statements by Breton, Nancy Cunard, and Sweeney.

Upon returning home from Brazil, Calder crafts a large brooch for Henrique Mindlin’s wife, Helena. The brooch is in the form of a figa—a hand with the thumb curled under the forefinger—a symbol of luck in Brazil. Thank you, thank you, thank you ever so much for the most beautiful figa I have ever

seen. You managed to make many females terribly envious of me, and this makes me oh! so happy! Calder eventually makes at least twenty pieces of jewelry in the figa motif, nearly all as gifts for family and friends.

Calder constructs his most ambitious mobile to date, International Mobile, for the Third International Exhibition of Sculpture, Philadelphia Museum of Art in collaboration with the Fairmount Park Art Association.

Happy As Larry, a play written by Donagh MacDonagh and directed by Burgess Meredith with sets by Calder, opens in New York at the Coronet Theatre.

The Calder family sails from New York on the Ile de France and arrives in Le Havre.

Galerie Maeght, Paris, exhibits “Calder: Mobiles & Stabiles.” Calder, encouraged by Christian Zervos (publisher of Cahiers d’Art) to exhibit at Galerie Maeght, also illustrates the catalogue and the exhibition poster. The Nationalmuseum, Stockholm, purchases a mobile

and the Musée National d’Art Moderne, Paris, purchases Le 31 Janvier.

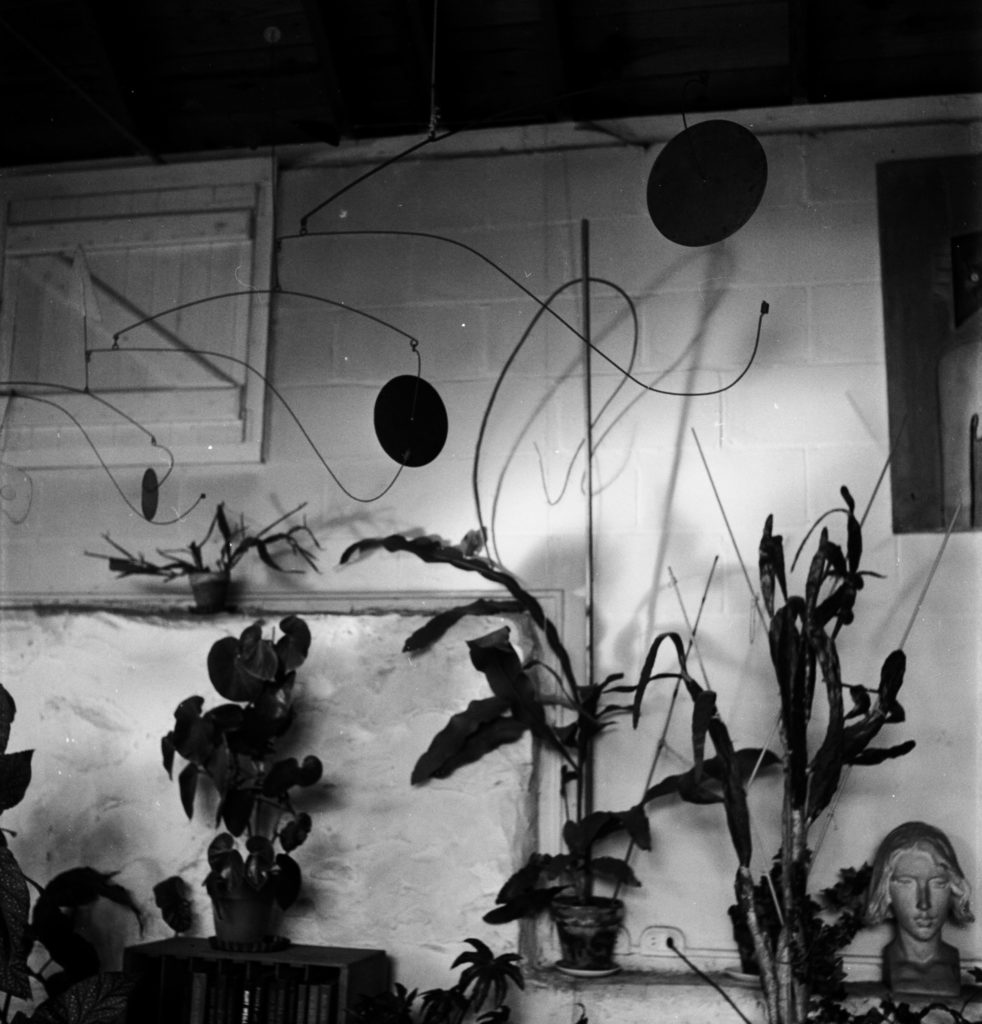

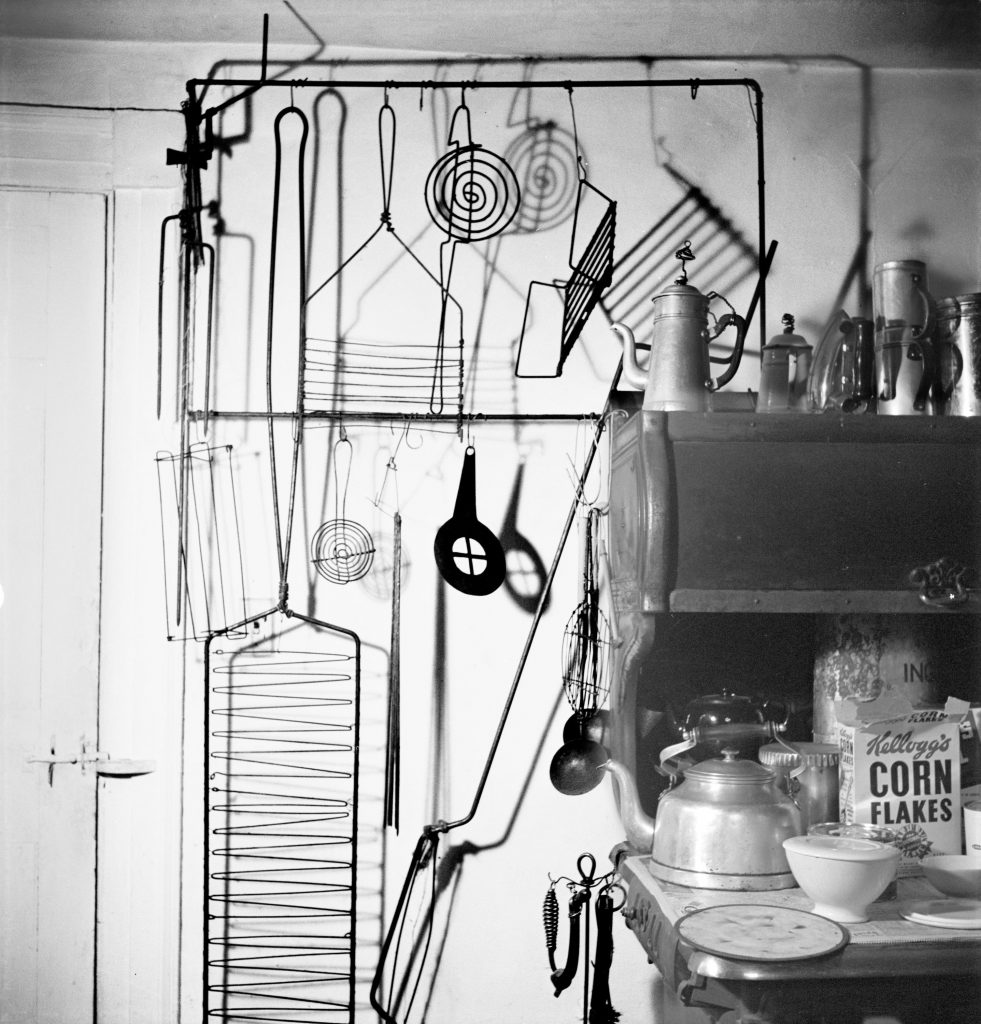

Matter photographs Calder’s Roxbury studio and home.

Calder is selected by the New York Times Book Review as one of the ten best children’s book illustrators of the last fifty years.

Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, exhibits “Calder,” a retrospective. Sweeney installs the exhibition while Calder recovers from an automobile accident.

After two years of production, Works of Calder previews at the Museum of Modern Art. The film was directed by Matter and produced and narrated by Burgess Meredith, with music by John Cage.

5 February: Calder participates in a symposium, “What Abstract Art Means to Me,” at the Museum of Modern Art in conjunction with their exhibition “Abstract Painting and Sculpture in America.”

Calder, Alexander. “What Abstract Art Means to Me: Statements by Six American Artists.” The Museum of Modern Art Bulletin, vol. 18, no. 3 (Spring 1951).

The idea of detached bodies floating in space, of different sizes and densities, perhaps of different colors and temperatures, and surrounded and interlarded with wisps of gaseous condition, and some at rest, while others move in peculiar manners, seems to me the ideal source of form. Read more

Curt Valentin Gallery, New York, exhibits “Alexander Calder: Gongs and Towers.” The catalogue texts are “Alexander Calder’s Mobiles” by Sweeney and “Calder” by Léger, with drawings by Calder of the objects exhibited.

Calder designs the sets and costumes for Nucléa, written by Henri Pichette. The costumes include two large silver necklaces and a silver bracelet.

The Calders visit Masson and his family in Aix-en-Provence. They ask Masson to find them a house to rent for the following year. From Aix-en-Provence they travel to Varengeville.

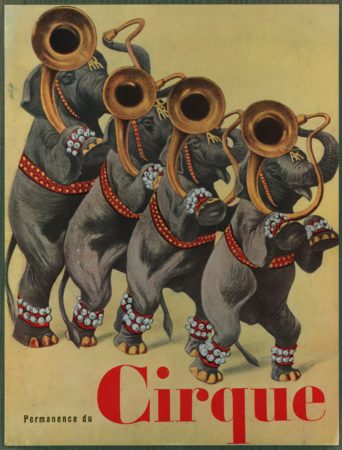

Calder, Alexander. “Voici une petite histoire de mon cirque.” In Permanence du Cirque. Exhibition Catalogue. Paris: Revue Neuf, 1952.

I would change the brightly colored rugs for almost every act to complement the costumes of the artistes, who often wore magnificent jewelry from Woolworth’s. In all there are about twenty acts with an intermission, peanuts, and exotic gramophone music played by my wife, who is an excellent conductor, and with the sounds of a tambourine, cymbals and a cardboard pipe for making the lion roar and if you like the big circus, then maybe you’ll like mine. Read more

Calder represents the United States in the XXVI Biennale di Venezia. Sweeney installs the exhibition and writes a short text for the exhibition catalogue. Calder wins the Grand Prize for sculpture.

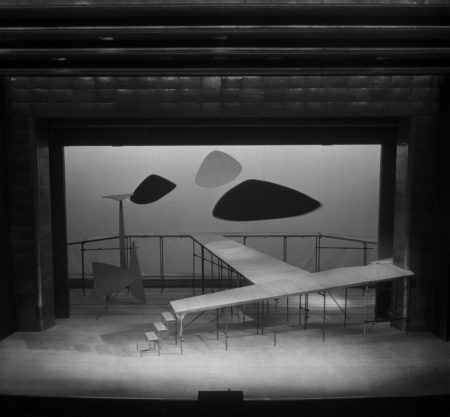

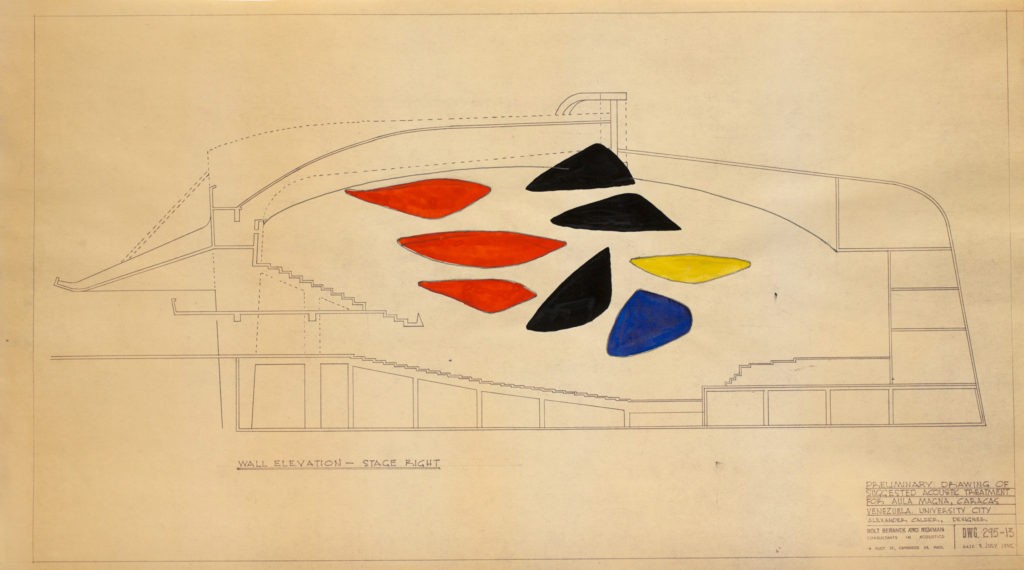

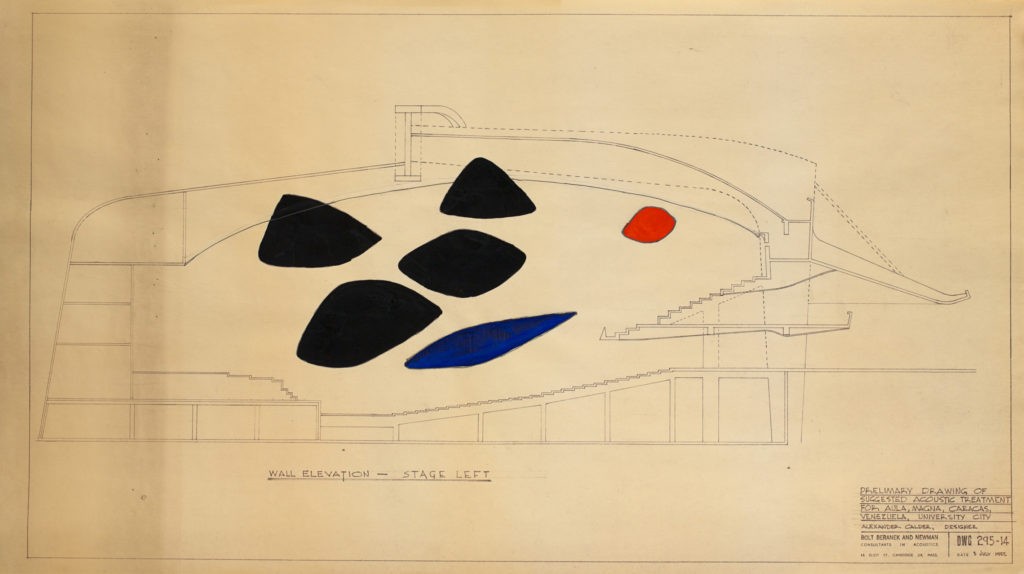

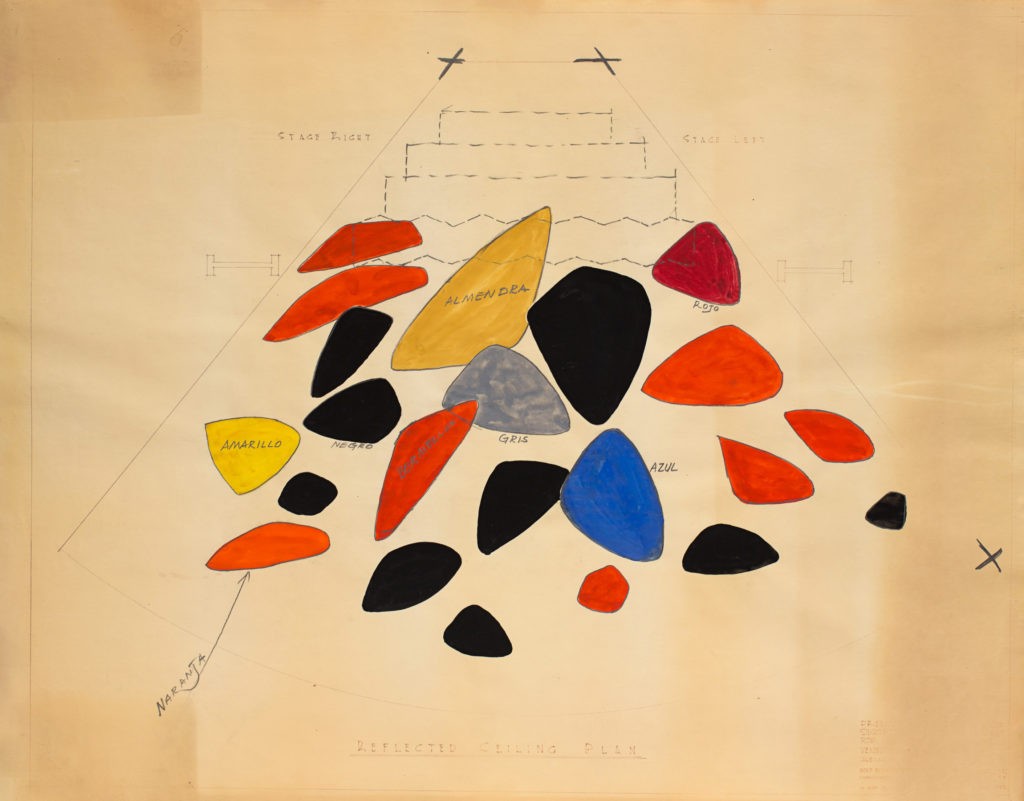

Calder accepts the commission from Carlos Raúl Villanueva, whom he met through Sert in 1951, to design an acoustic ceiling for Aula Magna, the auditorium of the Universidad Central de Venezuela. He collaborates with the engineering firm Bolt, Beranek, and Newman,

Cambridge, Massachusetts.

Calder arrives in Bonn on 10 September with an invitation from the German State Department to tour West Germany. After two days he travels to Munich, where he meets Bruno Werner, a journalist who reviewed his first Berlin exhibition in 1929. He continues on to Mannheim and

Darmstadt.

During a yearlong stay in Aix-en-Provence, Calder executed the first group of large-scale outdoor works and concurrently concentrated on painting gouaches. In 1954–55, he visited the Middle East, India, and South America, with trips to Paris in between, resulting in an astonishing output and range of work. Toward the late 1950s, Calder turned his attention to commissions both at home and abroad.