Featured Text

Letter Home

Esquire, vol. 61, no. 3 (March 1964). Originally published as “L’ombre de l’avenir” in Galerie Maeght, Paris. Alexander Calder: Stabiles. Exhibition Catalogue. 1963. Derrière le Miroir, no. 141 (November 1963).

Esquire, vol. 61, no. 3 (March 1964). Originally published as “L’ombre de l’avenir” in Galerie Maeght, Paris. Alexander Calder: Stabiles. Exhibition Catalogue. 1963. Derrière le Miroir, no. 141 (November 1963).

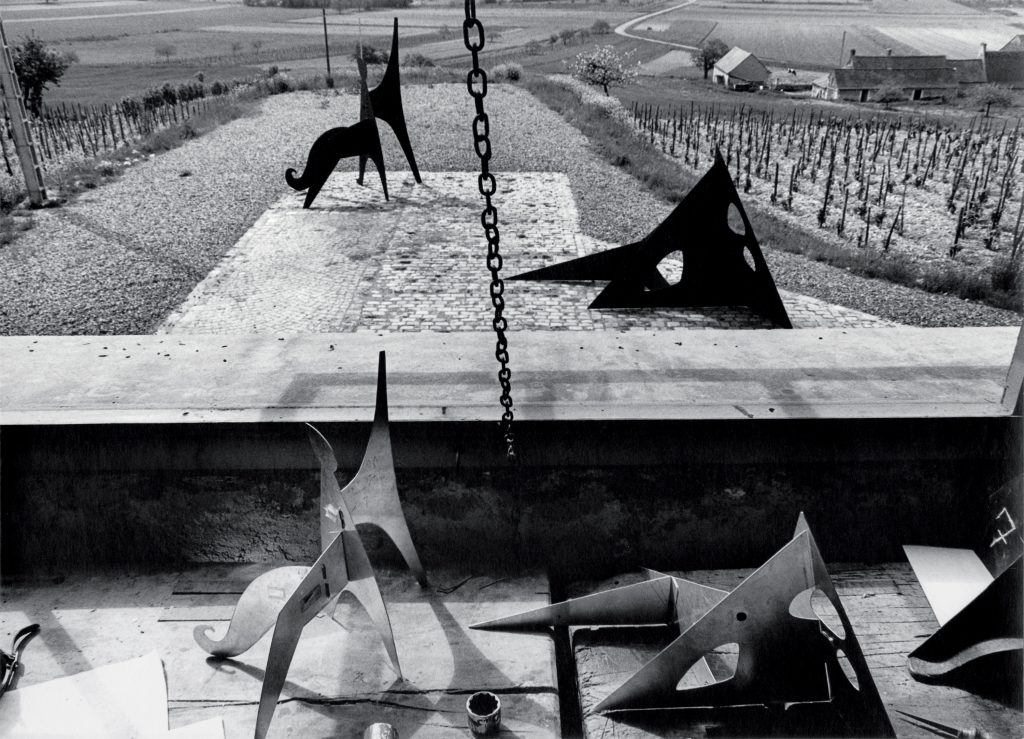

The huge barnlike structure hung on the lip of a high, gentle rise that looked down on the Valley of the Indre. In the moonlight it could have been part of a hill. We had had a fine dinner, with lots of red wine, in that strange, marvelous house of which two walls are the cliff it was built against, and now we were driving up here to look at this place, the “new studio,” because that was where the stuff was. This was the only place around that was big enough to hold them, and it was beautiful. Like everything that Calder touches, it seemed to have come alive with a life of its own, seemed to be both itself and something more, something that was not Calder, or anything else definable. The road wound up and around it in the moonlight. Four stories high overall, with a long, steep roof two stories high in itself, it consisted of two floors: a low-ceilinged cellarlike ground floor with a row of low arched doors opening onto a patio that hung over the valley like the top of a ski jump; and above that one huge long room, unceiled and three floors high, and reached by a plank bridge from the hillside behind. Almost half of the north side of the immense roof was glass for the north light; on the other side, half the wall that faced south across the Indre Valley was also of glass. But the impressiveness of the studio hardly counted compared to the impressiveness we found inside. In that lumbering way of his, Calder bent over slowly with the key and unlocked and threw open the big steel door, designed to let trucks enter. Then we stepped inside where the stuff was.

In the gloom and moonlight I had the impression the future was finally falling in on me, as I have often dreamed it will someday. Behind me I heard my wife gasp. Soaring, looming black shapes and streaks circled and dived on me from above and on all sides. Off to my left, a squat fat silent chief of a commanding officer sat patiently waiting his chance at me. How did the Old Man know all he knew? Out of his own freedom, artistic sensibility and imagination, he was showing me the real beauty of a future where such traits, and also things like himself, will no longer be tolerated to exist. How objective can one become? Behind us Calder had stepped unobtrusively away to let us look undisturbed. Now he ambled forward in that strangely graceful way, and muttered that he had a flashlight if we wanted it. I simply shook my head no, not wanting to speak, and stepped back into the doorway for a moment to clear my mind, and then began to really look.

Big as the big stone-barn building was, the new stabiles—the stuff—more than filled it up. So two of them had been mounted out on the ski-jump patio, and we descended to look at these in the moonlight. Calder, in his droll, dry way, told a funny story about one of them: Some rich town in Texas, for a memorial to a rich citizen who had willed the town the land for it, had commissioned Calder to do a piece for them, preferably a horse. When they saw the finished piece they complained that it didn’t look like a horse. “Well, it probably isn’t a horse,” Calder had said in answer. “I guess I didn’t feel like making a horse when I made it.” Result: no sale, and Calder still has the stabile. “I’m kind of glad though,” he told us, rubbing it affectionately, “because I like this one a lot.” He thought a moment. “I would like to do a horse sometime, though,” he added. “Do a lot with a horse.” We had a cigarette on the lip of the ski jump, looking out across the valley where scattered houses still had their lights on. Then we went back upstairs to look some more. We would return in the morning to look at them again by daylight. —And we would spend the rest of the whole next day looking at a lot of other things.

There is so much to look at around Calder’s place at Saché. He and his son-in-law, Jean Davidson, between them have some seven buildings and two caves; and there is hardly a corner, a table, a bench, a bookshelf that is not inhabited by some object droll or profound made by Calder’s restless, ever-questing hands and ever-probing fingers. The famous mobiles, with their gay, seemingly simple and yet curiously sorrowful colors, hang everywhere indoors; and the larger ones can be seen scattered across the grounds gently waving their various arms at you in the air. Of the seven buildings, four are at present current workshops for Calder; so this excludes only the two dwelling houses and Davidson’s old mill. In one he has his painting tables set up and is at work on numbers of whole series of gouaches in that peculiarly Einsteinian-Universe feeling that he gives them. In another he has some weird, fantastic moving bronzes he has been doing. The biggest shop, with its battered old workbench and jumble of tools with the sweat-stained homemade cardboard work visor lying on them, is his mobile workshop. Such a profusion of beauty and hard, sweaty work can become almost too much to encompass, and after a while your sight is so dazzled and concentrated that you cease even to look any more, and it is as though your eyes literally and actually reach out of you to feel of things, as if your eyes were hands.

During the rest of the evening as we sat talking and drinking red wine, it was the mobile workshop which kept drawing me and I would wander outside to switch on the light and look at it again. If the Vatican ordered all the cathedrals in the world to send all their precious stones and jewel-encrusted treasures to one grand exhibition, that exhibition would look like Calder’s mobile workshop. Maybe twenty recently finished ones hung in a jumbled confusion of color and line from the high ceiling. Others of different types stood or lay on various tables or benches. All of the clear, yet not so simple colors he likes to use, all of the various suggestive shapes combined to give me, under the bare electric bulb, the most jewel-like experience I’ve ever had. I remember one in particular: three black discs from which suspended four long red feathers on long drooping stems like wheat stalks when the heads are full, and below which (after two vaguely isosceles shapes to point the distinction) hung three yellow feathers continuing the motif, but on short stems so that they jutted upward toward their brothers, and the whole finished off at the bottom with that spectacular, striking red sun disc (which is so simple and yet so profoundly moving, and which has become Calder’s trademark and sort of cosmic symbol) seeming by some incredible alchemy to float entirely free of all the rest, entirely alone and suspended gravityless in air. None of the mobiles are ever really still, even in still air, I think. But when I would open the door, letting in a little breeze, they would begin to dance and bob and swing in that slow, sedate undersea motion his mobiles have and which I have never seen anywhere else except when a hundred fifty feet down among the gorgonia and sea-fan beds of the Caribbean.

Next morning, again, I kept being drawn back to the mobile workshop until it was time to go back up the hill to the big stuff: the stabiles. Calder had shown us photos of the huge Spoleto stabile, fifty-eight feet high and almost sixteen yards across, and I could estimate its immensity from automobiles sitting beside it, and found it fitting that the only place in Italy where they could build it was in the shipyards of Genoa! I have always thought of battleships when I see Calder stabiles. But all the information about the Spoleto stabile, incredible as it is, could not equal for me the laying of my hands on these smaller ones in Saché, their thick metal plates bolted and welded like modern ships of the line, which rested in the “new studio” up the hill.

But the marvelously powerful way in which they are put together is only a small part of their value and their meaning, as the exquisite dexterity of the mobiles and the unbelievable perfection of their balance are only a small part of their worth as sculpture. The thing that makes Calder unique as a sculptor is his sense of a cosmic mathematic. He is willing to believe equally in a nonspace as well as in space. Because of this, his stabiles (and his mobiles as well) are able to fill a given space without occupying it. This has been true for some time. But now it seems to me he has with these new stabiles pushed the concept even further. He has taken a given space and, by molding beautiful elements of steel around it, caused it to become nonspace. This was particularly evident in all the photos I saw of the Spoleto stabile. And when I studied closely these smaller ones in Saché, the same quality was there in them. I had the nervous feeling that if I walked in under one of the larger ones, I might not be there; that if I pushed my hand between elements or through a hole of the smaller ones, the hand would disappear. I wouldn’t drive a car under the Spoleto stabile for anything, because I could never be sure I would always come out on the other side! Where will Calder go from here?

It may be that when the astronauts and cosmonauts, with their crude instruments, get far enough out into space to discover nonspace, shove off for another solar system only to meet themselves coming back, they will find that Calder, with his peculiar cosmic, or Universal, or Einsteinian view, call it what you will, working quietly and alone in Saché and in Roxbury, will already have anticipated them, and stated their experiences.

Osborn, Robert. “Calder’s International Monuments.” Art in America, vol. 57, no. 2 (March–April 1969).

MagazineWhitney Museum of American Art, New York. Alexander Calder: July 22, 1898–November 11, 1976, Memorial Service. Memorial program. 1976.

Unpublished Document or ManuscriptLouisiana Museum of Modern Art, Humlebaek, Denmark. Alexander Calder: Retrospective. Exhibition catalogue. 1995. Louisiana Revy, vol. 36, no. 1 (Summer 1995).

Alexander S. C. Rower, License Plates

Magazine, Solo Exhibition CatalogueNational Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C. Alexander Calder: 1898–1976. Exhibition catalogue. 1998.

Arnauld Pierre, Staging Movement

Solo Exhibition CatalogueIn 1963, Calder completed construction of a large studio overlooking the Indre Valley. With the assistance of a full-scale, industrial ironworks, he began to fabricate his monumental works in France and devoted much of his later working years to public commissions. Calder died in New York in 1976 at the age of seventy-eight.