Featured Text

A Water Ballet

Theatre Arts Monthly, vol. 23, no. 8 (August 1939).

Theatre Arts Monthly, vol. 23, no. 8 (August 1939).

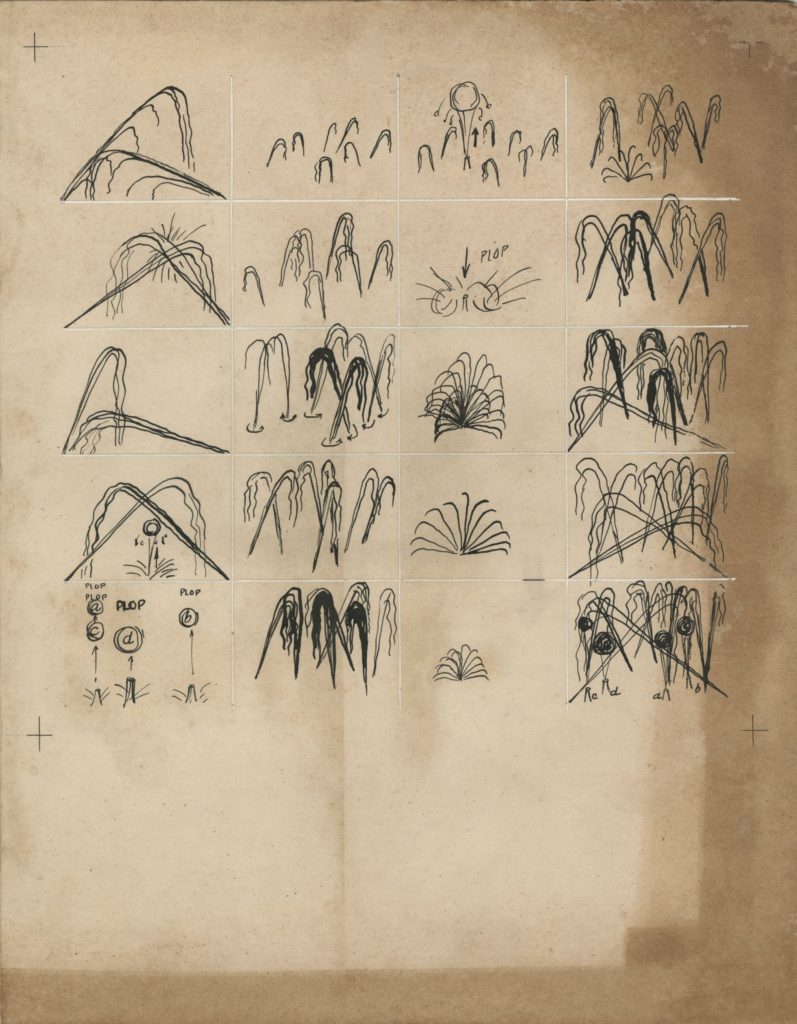

The facade of the Consolidated Edison Building at the World’s Fair is a concave quadrant, in front of which is a basin about 200 feet long and, at its greatest width, 50 feet wide. The rim of the basin bellies out at the left and recedes at the right until there is only a narrow strip of water, over which a bridge gives entry to the building. Along the facade of the building there are jets of water 5 feet apart which shoot directly upward, straight and slender, almost to the full height of the 40-foot building. This fountain facade is a part of the design by the architects of the building, Harrison and Fouilhoux. The centre of the water basin itself serves as the stage for a water ballet whose acting elements are jets of water from 14 nozzles which are designed to spurt, oscillate or rotate in fixed manners and at times as carefully predetermined as the movements of living dancers. The ballet is schemed to last 5 minutes, each time following the same fixed pattern, with 15 minutes or more between performances.

It occupies a space about 100 feet wide and 30 feet deep. At each end there is a nozzle which swings in a vertical plane between two positions, one almost vertical, the other more or less horizontal, pointing inward toward the centre. These two jets are used for the opening movement of the ballet.

For the second movement there are 4 nozzles, each of which projects into the air a sort of bomb, a large detached mass of water which gives off a considerable report when it falls back onto the surface of the lagoon.

Following a cannonade of these ‘bombs,’ 7 slender jets appear, shooting upward almost vertically and rotating slowly, generating long, slender inverted cones. They grow gradually in height until they are almost as high as the building and rotate gently all the while, some in one direction, some in the opposite. After a half minute of full height, they diminish slowly, and their fall is punctuated by a single ‘bomb.’

After this pattern the last nozzle comes into play, beginning gradually, lifting to its full height and then diminishing. It is a fan-shaped spray, originally designed to rotate, but since its installation it has been found more effective if left stationary in a plane parallel to the building, permitting it a larger size and more continuous visibility.

When the fan disappears, the 7 jets reappear, rise up to full height and stay at that point while the 2 end jets begin to play. The finale is reached with the end jets playing and cannonade.

Sweeney, James Johnson. “Alexander Calder: Movement as a Plastic Element.” Plus, no. 2 (February 1939).

MagazineMasson, André. “L’Atelier d’Alexander Calder.” Handwritten poem, 1942. Calder Foundation, New York.

Unpublished Document or ManuscriptCalder, Alexander. “À Propos of Measuring a Mobile.” Manuscript, 1943. Agnes Rindge Claflin papers concerning Alexander Calder, 1936-circa 1970s. Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution.

Unpublished Document or ManuscriptAddison Gallery of American Art, Andover, Massachusetts. 17 Mobiles by Alexander Calder. Exhibition catalogue. 1943.

Alexander Calder, Statement

Solo Exhibition CatalogueIn 1937, Calder completed Devil Fish, his first stabile enlarged from a model. He received two important commissions: Mercury Fountain (1937) and Lobster Trap and Fish Tail (1939). His first retrospective was held in 1938 at the George Walter Vincent Smith Gallery in Springfield, Massachusetts, followed by another in 1943 at the Museum of Modern Art in New York.