Soon after moving to Paris in 1926, Calder created his Cirque Calder. Made of wire and a spectrum of found materials, the Cirque was a work of performance art that gained Calder an introduction to the Parisian avant-garde. Calder continued to explore his invention of wire sculpture, whereby he “drew” with wire in three dimensions the portraits of friends, animals, circus themes, and personalities of the day. In 1928, he was given his first solo exhibition of these sculptures at the Weyhe Gallery in New York.

American painter Walter Kuhn organizes a stag dinner at the Union Square Volunteer Fire Brigade, Tip Toe Inn, New York, in honor of sculptor Constantin Brancusi’s first visit to the United States. Calder paints Firemen’s Dinner for Brancusi commemorating the event.

At his friend Betty Salemme’s house on Candlewood Lake in Sherman, Connecticut, Calder carves his first wood sculpture, Very Flat Cat, from an oak fence post.

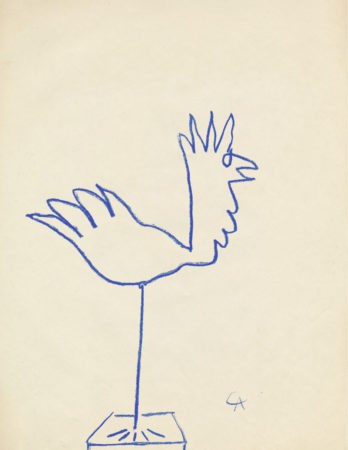

Calder moves into a tiny, one-room apartment at 249 West Fourteenth Street. There he makes his first wire sculpture, a sundial in the form of a “rooster on a vertical rod with radiating lines at the foot” to demarcate the hours.

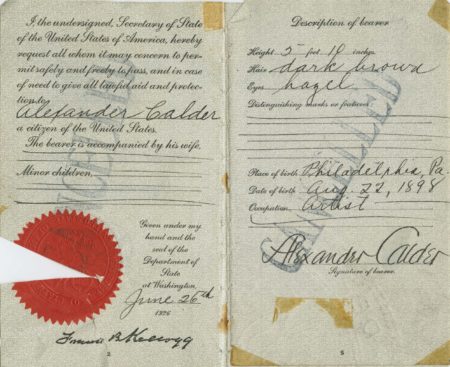

Calder receives his U.S. passport in preparation for his first voyage to Europe.

Calder enrolls in drawing classes at the Académie de la Grande Chaumière.

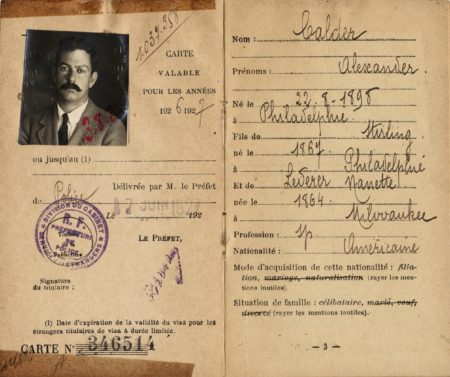

Calder’s French identity card is issued for 1926–27.

Calder establishes a studio at 22 rue Daguerre.

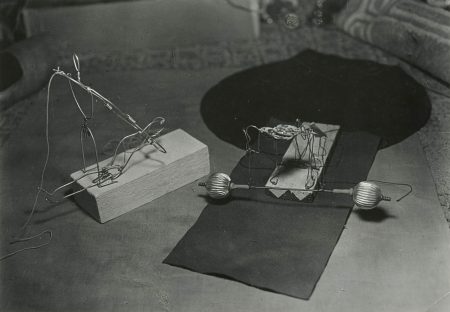

Calder begins creating Cirque Calder, a complex and unique body of art. Fashioned from wire, fabric, leather, rubber, cork, and other materials, Cirque Calder is designed to be performed for an audience by Calder. It develops into a multi-act articulated series of mechanized sculpture in miniature scale, a distillation of the natural circus. Calder is able to travel with his easily transportable circus and hold performances on both continents. Over the next five years, Calder continues to develop and expand this work of performance art to fill five large suitcases.

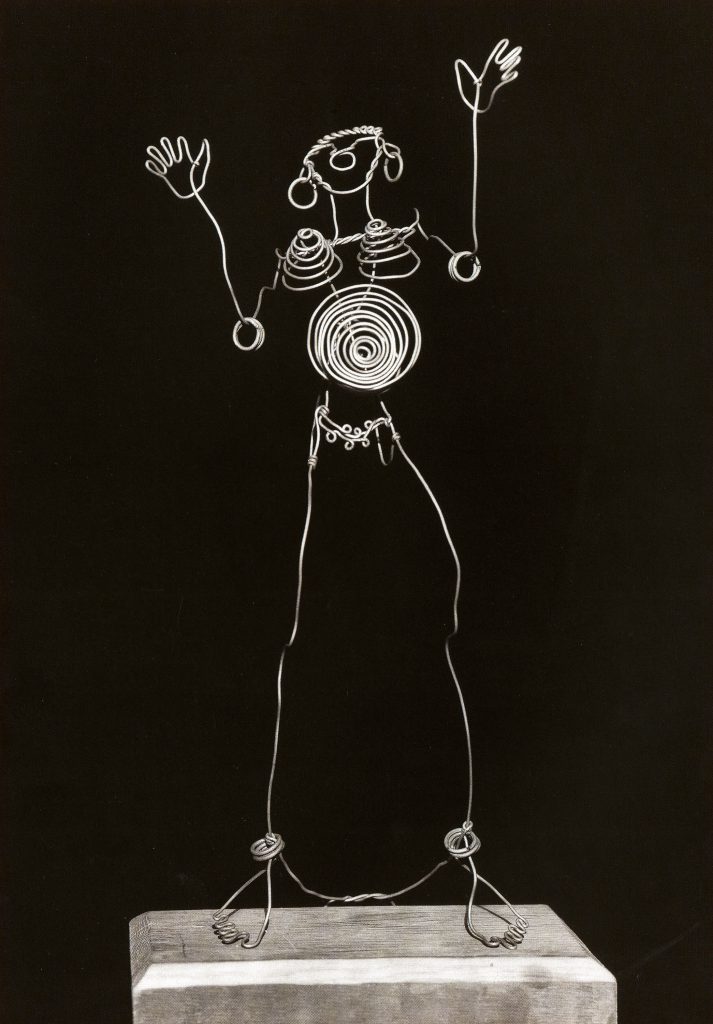

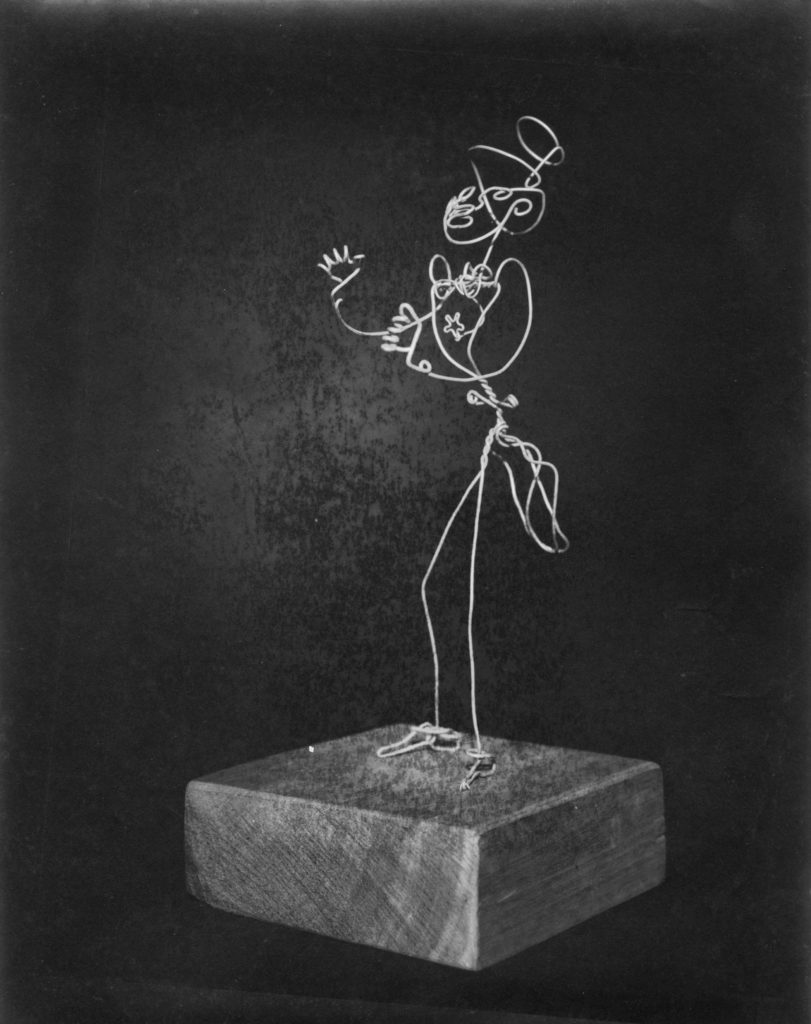

Calder makes his first formal wire sculptures, Josephine Baker I and Struttin’ His Stuff.

Réal brings Guy Selz and the circus critic, Legrand-Chabrier, to see Calder perform Cirque Calder. Legrand-Chabrier admires Calder’s work and writes several articles on the Cirque.

Oh, these are stylized silhouettes, but astonishing in their miniature resemblance, obtained by means of luck, iron wire, spools, corks, elastics . . . A stroke of the brush, a stroke of the knife, of this, of that; these are the skillful marks that reconstruct the individuals that we see at the circus.

Here is a dog who seems like a prehistoric cave drawing with a body of iron wire. He will jump through a paper hoop. Yes, but he may miss his mark or not. This is not a mechanical toy . . .

All of this is arranged and balanced according to the laws of physics in action so that it allows for the miracles of circus acrobatics.

The New York Herald, Paris, publishes an article about Calder and his decision to make toys:

I began by futuristic painting in a small studio in the Greenwich Village section of New York. It was a lot different to engineering but I took to my newfound art immediately. But it seemed that during all of this time I could never forget my training at Stevens, for I started experimenting with toys in a mechanical way. I could not experiment with mechanism as it was too expensive and too bulky so I built miniature instruments. From that the toy idea suggested itself to me so I figured I might as well turn my efforts to something that would bring remuneration. From then on I have constructed several thousand workable toys.

Calder travels to Oshkosh, Wisconsin, to contract with Gould Manufacturing Company. He designs prototypes for a series of plywood animal Action Toys.

Weyhe Gallery, New York, exhibits “Wire Sculpture by Alexander Calder.” Calder creates a hanging sign, Wire Sculpture by Alexander Calder, for the gallery window. Pioneer Woman is sold to Marie Sterner, an art dealer.

Calder exhibits four sculptures, including Romulus and Remus and Spring, in the Twelfth Annual Exhibition of the Society of Independent Artists at the Waldorf-Astoria, New York.

Calder spends the summer working on wood and wire sculptures at the Peekskill, New York, farm of J. L. Murphy, the uncle of fraternity brother Bill Drew.

I worked outside on an upturned water trough and carved the wooden horse bought later by the Museum of Modern Art, a cow, a giraffe, a camel, two elephants, another cat, several circus figures, a man with a hollow chest, and an ebony lady bending over dangerously, whom I daringly called Liquorice.

Calder arrives at Le Havre after a voyage from New York on the De Grasse. He returns to Paris, where he rents a small building behind 7 rue Cels to use as his studio. When I returned to Paris in Nov. 28 I was a “wire sculptor” as I put it, also “le roi du fil de fer.”

Calder exhibits Romulus and Remus and Spring at the Salon de la Société des Artistes Indépendants, Paris. The public reaction is a mixture of confusion and delight. One critic remarks,

At first, I believed that electricians had forgotten their electrical wire in this room, but as I passed, a wire became agitated and I noticed that it represented the head of a she-wolf. Another tangle of electrical wire represented, by all evidence, a giant young woman. Another critic advises, All the same, look at them. Who knows if the sculpture of Mr. Calder is not that of the future? In any case, it doesn’t spawn melancholy.

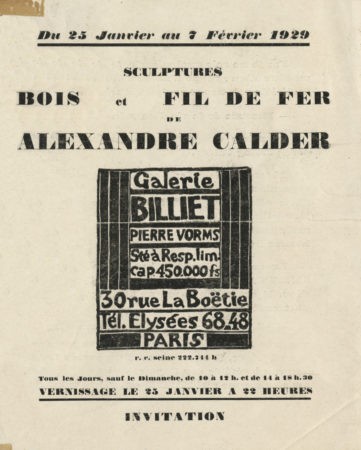

Galerie Billiet-Pierre Vorms, Paris, exhibits “Sculptures bois et fil de fer de Alexandre Calder.” Pascin writes the preface for the exhibition catalogue.

Jules Pascin, Statement

Galerie Billiet-Pierre Vorms, Paris. Sculptures bois et fil de fer de Alexandre Calder. Exhibition catalogue. 1929.

By some miracle, I became a member of a group of Aces of American Art, a Society of very successful painters and sculptors!!! Read more

—The fortunes of the life of an itinerant painter! Read more

The same luck led me to meet the father Stirling Calder. Read more

Away from New York at the time of our exhibition, I cannot testify to the success of our effort; but in any case, I can attest that Mr. Stirling Calder, who is one of our best American sculptors, is also the handsomest man in our Group. Read more

Returning to Paris, I met his son SANDY CALDER, who at first sight left me quite disillusioned. He is less handsome than his Dad! Honestly!!! Read more

But in the presence of his works, I know that he will soon make his mark; and that despite his appearance, he will exhibit with spectacular success alongside his Dad and other great artists like me, PASCIN, who’s talking to you….! Read more

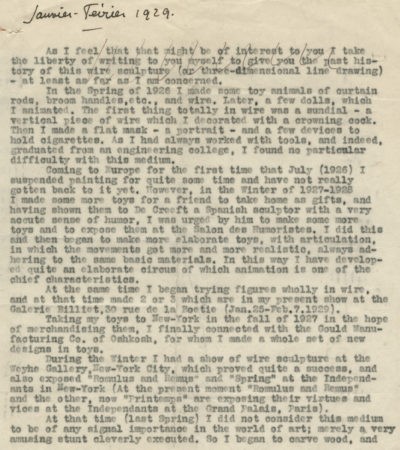

Calder, Alexander. Statement on Wire Sculpture. Manuscript, 1929. Calder Foundation, New York. Typed and annotated by Jean Davidson.

There is one thing, in particular, which connects them with history. One of the canons of the futuristic painters, as propounded by Modigliani, was that objects behind other objects should not be lost to view, but should be shown through the others by making the latter transparent. The wire sculpture accomplishes this in a most decided manner. Read more

Weyhe Gallery, New York, exhibits “Wood Carvings by Alexander Calder.” Calder writes to his parents about their thoughts on the exhibition. I’m glad you think the show looked well, for I was afraid they would clutter it up and detract from things.

Sacha Stone, a German photographer, sees Calder perform Cirque Calder at the rue Cels studio. He suggests that Calder perform and exhibit in Berlin.

Galerie Neumann-Nierendorf, Berlin, presents “Alexander Calder: Skulpturen aus Holz und aus Draht.” Chantal Quenneville Hallis a French paintrix was there and I made a wire fly dangling from a beam attached to a collar. That was about my first jewelry.

André Kertész photographs Calder at his rue Cels studio.

Calder embarks for New York on the De Grasse, bringing Cirque Calder with him. During the voyage, he meets Edward Holton James and his daughter Louisa.

So once on board the De Grasse, I started walking the deck. I overtook an elderly man and a young lady. I could only see them from the back, so I reversed my steps the better to see them face on. Upon coming abreast of them the next time around, I said, “Good evening!” And the man said to his daughter, “There is one of them already!” He was Edward Holton James, my future father-in-law. She was Louisa. Her father had just taken her to Europe to mix with the young intellectual elite. All she met were concierges, doormen, cab drivers—and finally me.

Calder performs Cirque Calder at Hawes’s couture house, 8 West Fifty-sixth Street, New York.

Calder stays with his friend, book designer Robert Josephy, at Beekman Place and Fiftieth Street.

Josephy was very enthusiastic over my circus. This encouraged me and while at his house, I worked on it very hard. He helped me. We made the chariot race and the lion tamer, and it got to be quite a full blown circus, growing from two suitcases into five.

Calder creates his first formal mechanized sculpture, Goldfish Bowl, and presents it to his mother as a Christmas gift. For his father, he makes a brass wire fish. In a letter to Peggy, Nanette writes,

He made me a fish tank of brass wire, with two fish that wiggle as you turn a crank made also of wire. Waves are indicated along the top. For your Dad a large fish that is now hanging from the electric light. Peggy, it is remarkable. One wire beginning at his tail, running along the backbone to the head where the eyes and mouth are faultlessly placed. Then the wire loops around the back bone as it travels back to form the other half of the tail. This is hard to describe, but it is really wonderful as is the fish bowl in which the fishes bend as tho [sic] swimming.

Calder sails for Spain on the Spanish freighter Motomar. The ship docks briefly in Málaga and Calder explores the town. Two days later, Calder debarks in Barcelona.

I went to the Hotel Regina, in a little room up somewhere high. It was then I decided that I liked white walls and red tile flooring . . . I tried to find Miró, but I guess he was away in the country. I went to a bullfight, and then on to Paris by train.

Calder rents a studio at 7 Villa Brune.

Calder makes thirteen plaster sculptures and casts eight of them in bronze at the Fonderie Valsuani, Paris. There is a very fine bronze foundry at the end of Villa Brune—so I am going to delve into cire perdue.

While in Calvi, Calder collects fragments of ancient pottery and fashions the pieces into a necklace.

I meant to write you a birthday letter two days [ago] but I made you a necklace instead—having brought along pliers + wires, and found bits of things along the parapets of the citadel, to put into it . . . I have been making a lot more wire jewelry—and I think I’ll really do something with it, eventually.

Kiesler introduces Calder to composer Edgard Varèse and Calder makes a wire portrait of him.

Following a visit in October of 1930 to Mondrian’s studio, where he was impressed by the environment and actuation of space, Calder made his first wholly abstract compositions and developed the kinetic sculpture now known as the mobile. Coined for these works by Marcel Duchamp in 1931, the word “mobile” refers to both “motion” and “motive” in French. He also created stationary abstract works that Jean Arp dubbed “stabiles.”