During a yearlong stay in Aix-en-Provence, Calder executed the first group of large-scale outdoor works and concurrently concentrated on painting gouaches. In 1954–55, he visited the Middle East, India, and South America, with trips to Paris in between, resulting in an astonishing output and range of work. Toward the late 1950s, Calder turned his attention to commissions both at home and abroad, producing such recognizable works as .125 (1957), a mobile hung in John F. Kennedy Airport in New York, and Spirale (1958), a major commission for U.N.E.S.C.O. in Paris. In Italy, Calder created Teodelapio, a stabile over 58 feet tall, for the 1962 Spoleto Festival.

The Calders arrive in the hamlet of Les Granettes in Aix-en-Provence. Their house, Mas des Roches, has little water and no electricity. Calder uses the carriage shed as his studio, where he works on gouaches. At a blacksmith shop nearby, he makes a series of large standing

mobiles conceived for the outdoors.

Calder performs Cirque Calder at Galerie Maeght Paris.

Back in Aix-en-Provence, the Calders find another house nearby, Malvalat, which has running water and electricity. Calder sets up a studio on the third floor and continues to concentrate on gouaches.

Calder visits Jean and sees his renovated mill house in Saché. Calder agrees to a trade of three mobiles for François Premier, a dilapidated seventeenth-century stone house built adjoining a cliff on Jean’s property.

Calder plans a trip to Beirut to visit his friend Henri Seyrig and to make a mobile commissioned by Middle East Airlines.

Museu de Arte Moderna, São Paulo, Brazil, presents the II Bienal. United States representation consists of three exhibitions prepared by the Museum of Modern Art, New York: two group shows and a solo show devoted to works by Calder.

The Calders arrive in Beirut after a stop in Limassol, Cyprus. They reside with the Seyrigs for a month, visiting Syria and Jordan by car.

Calder is given a room to serve as a studio in the Middle East Airlines ticket office, which is under construction.

The renovation of François Premier is completed.

Calder’s dealer, Curt Valentin, dies in Italy.

Belgiojoso, Peressutti & Rogers of Milan build a labyrinth for the X Triennale di Milano at the Uffici Palazzo dell’arte al Parco. Calder’s Le Cagoulard is installed in the center, and Saul Steinberg’s drawings are on the walls.

Galerie Maeght, Paris, exhibits “Aix. Saché. Roxbury. 1953–54.” The catalogue texts are “Poème offert à Alexander Calder et à Louisa” by Henri Pichette and “Calder” by Frank Elgar.

A visa is issued for the Calders’ trip to India. Calder and Louisa have been invited by Gira Sarabhai, an architect and designer, to a tour of India in exchange for works of art.

The Calders arrive in Bombay. They journey by train to Gira Sarabhai’s home in Ahmedabad, where Calder makes eleven sculptures and some gold jewelry.

Calder arrives in Caracas. He sets up a studio at the metal shop of the Universidad Central de Venezuela and sees Acoustic Ceiling installed in Aula Magna for the first time. Louisa plans to join Calder in Caracas, but a tornado hits Connecticut and causes extensive flooding; she

cancels her trip.

Villanueva arranges “Exposición Calder” at Museo de Bellas Artes, Caracas.

Sandra Calder and Jean Davidson are married in Saché. As a wedding present, Miró gives Sandra a drawing.

The Calders and Davidsons leave Paris and arrive in Germany, where Calder has been commissioned to make a stabile for the American Consulate in Frankfurt. The Calders stay at the Frankfurter Hof. Calder works with the bridge builders Fries et Cie to construct the monumental

stabile Hextopus.

Calder completes his fountain commission Water Ballet for the General Motors Technical Center, Warren, Michigan. There is a dedication on 15 May.

“About my method of work: first it’s the state of mind. Elation. I only feel elation if I’ve got ahold of something good. I used to begin with fairly complete drawings, but now I start by cutting out a lot of shapes. Next, I file them and smooth them off. Some I keep because they’re pleasing or dynamic. Some are bits I just happen to find. Then I arrange them, like papier collé, on a table, and ‘paint’ them—that is, arrange them, with wires between the pieces if it’s to be a mobile, for the overall pattern. Finally I cut some more on them with my shears, calculating for balance this time.” Read more

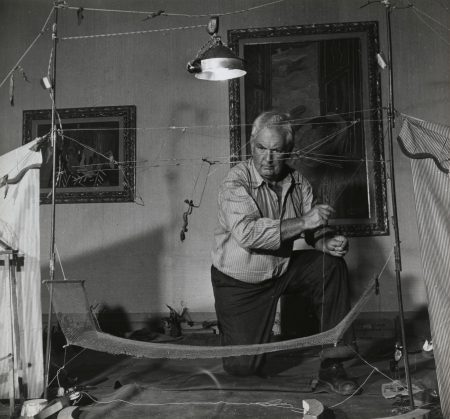

Arnold Newman photographs Calder in his Roxbury home and studio.

The Committee of Art Advisors at UNESCO approves Calder’s maquette for a standing mobile. Titled Spirale, the mobile top is made by Calder at Segré’s Iron Works in Connecticut and the stabile bottom is made with the collaboration of Jean Prouvé in France.

Alexander Calder, Statement

World House Galleries, New York. 4 Masters Exhibition: Rodin, Brancusi, Gauguin, Calder. Exhibition catalogue. 1957.

At Waterbury Iron Works in Connecticut, Calder finishes the mobile commissioned by the Port Authority of New York. He initially titles it .125, the gauge of the aluminum elements, although the work is later dubbed Flight. The mobile is placed in a storeroom near the International Arrivals

Building of Idlewild Airport (now John F. Kennedy International Airport), where it is to be installed upon completion of the terminal.

While visiting Ritou Nitzschke and André Bac in La Roche Jaune, Brittany, the Calders buy an old customs house, Le Palud, located at the mouth of the Tréguier River. A few times a year, at high tide, the house site becomes an island.

Uffici Palazzo dell’Arte al Parco, Milan, exhibits the XI Triennale di Milano. Calder makes the stabile Funghi Neri, enlarged from a maquette for the exhibition.

Calder and Louisa see .125 installed in the International Arrivals Terminal of John F. Kennedy Airport for the first time.

Calder completes the motorized, monumental sculpture The Whirling Ear, a commission made for the pool in front of the United States Pavilion at the Brussels Universal and International Exhibition. The sculpture was made by Calder at Gowans-Knight in Watertown,

Connecticut.

Carnegie Institute, Pittsburgh, presents the 1958 Pittsburgh Bicentennial International Exhibition of Contemporary Painting and Sculpture. Calder wins first prize in the sculpture category for Pittsburgh, a monumental mobile, which is purchased by G. David Thompson

and donated to Allegheny County. It is installed at the Greater Pittsburgh International Airport.

Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam, exhibits “Alexander Calder, Stabilen, Mobilen.” The catalogue texts are “Stabiles” by Georges Salles and “Calder und die mobiles” by Willem Sandberg. The exhibition travels to Hamburg, Krefeld, Mannheim, Wuppertal, and Zurich.

The Calders depart Paris and arrive in Rio de Janeiro, where they spend a month at the Gloria Hotel. During their stay, they visit Brazil’s new capital, Brasília.

The Calders return to Brazil for the Carnaval.

Calder’s mother, Nanette Lederer Calder, dies.

On their way to Le Havre, Calder and Louisa pay a visit to painter Pierre Tal-Coat in Normandy. Calder is envious of the size of his studio and is inspired to build a much larger studio of his own:

But the size of the studio gnawed at me the moment I saw it, and I became very jealous. So, after our arrival in Roxbury, I immediately wrote Jean at the Moulin Vert, in Saché, asking to have a big studio built as soon as possible.

Kuh, Katharine. “Alexander Calder.” In The Artist’s Voice: Talks with Seventeen Artists. New York and Evanston, Illinois: Harper & Row, 1962.

Question: How do your mobiles differ from your stabiles in intention? Read more

Calder: Well, the mobile has actual movement in itself, while the stabile is back at the old painting idea of implied movement. You have to walk around a stabile or through it—a mobile dances in front of you. You can walk through my stabile in the Basel museum. It’s a bunch of triangles leaning against each other with several large arches flying from the mass of triangles. Read more

In a letter to Giovanni Carandente, Calder agrees to a proposal to make a sculpture for the Spoleto Festival in Italy. He decides to make “a stabile, which will stand on the ground, + arch the roadway.” His work results in Teodelapio, a monumental stabile, which is completed in

August 1962.

Tate Gallery, London, exhibits “Alexander Calder: Sculpture–Mobiles,” a retrospective. The catalogue’s introduction is written by Sweeney.

In 1963, Calder completed construction of a large studio overlooking the Indre Valley. With the assistance of a full-scale, industrial ironworks, he began to fabricate his monumental works in France and devoted much of his later working years to public commissions. Calder died in New York in 1976 at the age of seventy-eight.