In 1963, Calder completed construction of a large studio overlooking the Indre Valley. With the assistance of a full-scale, industrial ironworks, he began to fabricate his monumental works in France and devoted much of his later working years to public commissions. Some of his most important projects include: Trois disques I for the 1967 exposition in Montreal; El Sol Rojo for the 1968 Mexico City Olympic Games; and La Grande vitesse for Grand Rapids, Michigan, in 1969, the first public art work funded by the National Endowment for the Arts. Major retrospectives of Calder’s work were held at the Guggenheim Museum in New York (1964); Museum of Fine Arts, Houston (1964); Musée National d’Art Moderne, Paris (1965); the Fondation Maeght in Saint-Paul-de-Vence, France (1969); and the Whitney Museum of American Art, New York (1976). Calder died in New York in 1976 at the age of seventy-eight.

Hans Richter directs and films Alexander Calder: From the Circus to the Moon.

After eighteen months, the new studio at Le Carroi is completed.

The Calders spend two weeks in Morocco; they visit Marrakech, Fès, Ouarzazate, and Casablanca.

It may be that when the astronauts and cosmonauts, with their crude instruments, get far enough out into space to discover nonspace, shove off for another solar system only to meet themselves coming back, they will find that Calder, with his peculiar cosmic, or Universal, or Einsteinian view, call it what you will, working quietly and alone in Saché and in Roxbury, will already have anticipated them, and stated their experiences. Read more

Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York, exhibits “Alexander Calder: A Retrospective Exhibition.” Thomas M. Messer curates the exhibition, which travels to St. Louis, Toronto, Milwaukee, and Des Moines.

Before leaving for France, Calder meets with I. M. Pei to discuss a large stabile for the Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

Musée National d’Art Moderne, Paris, exhibits “Calder,” a retrospective. Jean Cassou writes the catalogue preface.

Calder designs sets for Eppur Si Muove, a ballet choreographed by Joseph Lazzini and performed at the Marseilles Opera.

Architect Harry Seidler and wife Penelope visit the Calders in Roxbury. Two years later, Calder completes the commission of Crossed Blades for the Australia Square Tower.

Calder dedicates Le Guichet, a monumental stabile installed in Lincoln Center Plaza, New York.

Calder, a member of Artists for SANE (Committee for a Sane Nuclear Policy), participates in a march to protest against the Vietnam War in Washington, D.C.

Calder completes the monumental standing mobile Chef d’orchestre for Earle Brown’s Calder Piece. The mobile functions as both a “conductor,” determining the sequence and speed of the music, and as one of the instruments whereupon the elements are struck or “played.”

On behalf of SANE, the Calders publish a full-page ad in the New York Times: A New Year, New World. Hope for: An end to hypocrisy, self-righteousness, self interest, expediency, distortion and fear, wherever they exist. With great respect for those who rightly question brutality, and

speak out strongly for a more civilized world. Our only hope is in thoughtful Men—Reason is not treason.

In a hopeful gesture, Calder donates Object in Five Planes, a monumental stabile, to the United States Mission at the United Nations, New York, and dubs it Peace. The dedication ceremony takes place in May, when Calder returns from Europe.

Pantheon Books publishes Calder: An Autobiography with Pictures. Calder had been dictating the text to his son-in-law, Jean Davidson, over the previous year and a half.

Calder attends the dedication of the monumental stabile La Grande voile in McDermott Court at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

Calder and Louisa fly from Paris to Monaco to see his monumental standing mobile Quatre lances, recently installed above a pool on the esplanade of the Centennial Hall. They attend the dedication on the morning of 20 December with Princess Grace and Prince Rainier, returning to Paris that afternoon.

Calder makes a gift of the large standing mobile Frisco to the Museo de la Habana, Cuba. The Cuban Government issues a postage stamp of it.

Calder Piece, written by Earle Brown and featuring Calder’s Chef d’orchestre, is performed by Diego Masson and the Percussion Quartet of Paris at the Théâtre de l’Atelier. After the premiere, Calder remarks, I thought you were going to hit it harder.

Mathias Goeritz, an architect, writes to Calder in Saché, inviting him to create a stabile for the 1968 summer Olympic Games in Mexico City; Calder agrees.

Calder’s monumental stabile in unpainted stainless steel, commissioned by the International Nickel Company, is presented at the 1967 International and Universal Exposition (Expo ’67) in Canada, where the theme is “Man and His World.” I called it Three Discs, but

when I got over to Canada, they wanted to call it Man.

New York City holds an outdoor group exhibition, “Sculpture in Environment.” Given the choice of any site in the city, Calder places two stabiles, Little Fountain and Triangle with Ears, in Harlem.

Calder is awarded the Officer of the Légion d’Honneur of France, possibly on the opening date of the exhibition. The presentation is made by Henri Hoppenot, former ambassador to Washington.

Calder’s Work in Progress is performed by the Teatro dell’Opera, Rome. For thirty years I have been thinking about a production that would be entirely mine, form and music working together. I long ago discussed this with Massine, but he insisted on having dancers. I later made

stage sets, but this is not exactly what I wanted to do … for Satie’s Socrate, Pichette’s Nucléa, John Butler’s The Glory Folk in Spoleto, for Joe Lazzini in Marseille. The idea of a production that was totally mine had already come to me in spirit in 1926 when I finished the Cirque, and when I tried to frame it in a stage opening, amusing myself by thinking it an actual theatre.

The Calders return to Mexico City, where they view El Sol Rojo in place at Aztec Stadium.

Calder builds a new house adjacent to the Le Carroi studio in Saché.

Osborn, Robert. “Calder’s International Monuments.” Art in America, vol. 57, no. 2 (March–April 1969).

I try something new each time. With the model at three meters you can wobble it and see where it gives, where the vibrations occur, and then put your reinforcement there. If a plate seems flimsy, I put a rib on it, and if the relation between the two plates is not rigid, I put a gusset between them—that’s the triangular piece—and butt it to both surfaces. How to construct them changes with each piece; you invent the bracing as you go, depending on the form of each object. Read more

Janey Waney, commissioned by the N.K. Winston Corporation, is installed at the Smith Haven Mall in the Long Island village of Lake Grove. The force behind the site-specific project is the developer’s wife, Jane Holzer—or “Baby Jane,” a star of Andy Warhol’s films––for whom the sculpture was named.

Fondation Maeght, Saint-Paul-de-Vence, France, exhibits “Calder,” a retrospective. Calder installs Morning Cobweb, a monumental walk-through stabile, as the entrance to the exhibition.

Calder attends the dedication ceremony for his commissioned monumental stabile Gwenfritz, which is installed outside the Museum of History and Technology, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C.

The Calders move into the new house at Saché.

Louisa Calder, Le Carroi house, Saché, 1976

Photograph by Pedro Guerrero © Pedro GuerreroLouisa Calder, Le Carroi house, Saché, 1976

Calder is commissioned by Klaus Perls, Robert Graham, and Morton Rosenfeld to design a sidewalk strip on Madison Avenue between Seventy-eighth and Seventy-ninth Streets.

Calder designs sets and costumes for the ballet Amériques, choreographed by Norbert Schmuki, scored by Edgard Varèse, and performed by the Ballet-Théâtre Contemporain in Amiens, France.

The American Academy of Arts and Letters and the National Institute of Arts and Letters awards Calder the Gold Medal for Sculpture. Calder’s work is shown in the Academy’s group exhibition from 27 May–20 June.

The Calders sponsor an ad in the New York Times calling for Richard Nixon’s impeachment: Upon the Impeachment of Richard Nixon,

for high crimes and misdemeanors, the Constitution of the United States, provides that he, among others shall be removed from office . . . for conviction of, treason, bribery, or other high crimes and misdemeanors.

The Board of Trustees of the National Gallery of Art commissions Calder to make a monumental sculpture for its new building. The mobile, designed specifically for the central court of the National Gallery’s East Building, is completed and installed after Calder’s death in

1976.

Calder attends the dedication ceremony for the monumental stabile Stegosaurus at the Alfred E. Burr Memorial Mall in Hartford. Following the event, he receives an honorary Doctor of Fine Arts from the University of Hartford.

Flying Colors makes its inaugural flight from Dallas Love Field to Los Angeles, Chicago, and New York City—where the Calders disembark—before continuing to Washington D.C., Miami, and Latin America.

Friends on board with the Calders include Ruth and Leonard Horwich, Jean Lipman, Dorothy Miller, Nancy Mulnix, Elodie and Robert Osborn, Andi Schlitz, and Leslie and Rufus Stillman; family members include the Calders’ daughter Mary, who is joined by husband Howard and sons Holton and Alexander, and Calder’s sister, Peggy.

Calder accepts the Commandeur de la Légion d’Honneur of France; Michel Debré, the former French premier, presents the award.

Calder donates the monumental sculpture Totem-Saché, installed in the main square of the town of Saché.

Perls Galleries, New York, exhibits “Alexander Calder: Crags and Critters of 1974.”

The festival “Alexander Calder Day” in Chicago includes a circus parade with the Schlitz forty-horse hitch and the dedications of the motorized Universe at the Sears Tower and the monumental stabile Flamingo at the Federal Center Plaza. Calder is given a key to the city by Mayor Richard M. Daley.

The Calders visit Israel to discuss a monumental sculpture project with the Mayor of Jerusalem, Teddy Kollek. Jerusalem Stabile I is completed in 1976 and Louisa attends the dedication ceremony in 1977.

Prompted by Calder’s project with Braniff International Airways to paint a DC-8 jet, French auctioneer and racecar driver Hervé Poulain commissions Calder to design the first-ever BMW Art Car.

Flying Colors is exhibited at the Thirty-first Paris Air Show at Le Bourget. On 29 and 30 May, Calder hand paints the two starboard engine cowlings with Le Poisson and L’Aigle, respectively.

Calder attends the Le Mans 24-Hour race, where his BMW Art Car is driven by Poulain, Jean Guichet, and Sam Posey. Due to a mechanical failure relating to the driveshaft, the car does not complete the race.

Calder celebrates his birthday with a large party at Le Carroi. Every reveler is given a small gouache.

The Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, with Jean Lipman as curator, exhibits “Calder’s Universe,” a major retrospective. The exhibition travels to fifteen cities throughout the United States and Japan.

President Gerald Ford offers the Medal of Freedom to Calder. Calder replies, I was pleased to receive your invitation last week, but felt I could not accept in a case where my acceptance would imply my accord with the harsh treatment meted out to conscientious objectors and

deserters. As from the start I was against the war and now am working with “amnesty” I didn’t feel I could come to Washington. When there will be more justice for these men I will feel differingly [sic]. Ford posthumously awards Calder the Medal of Freedom. Louisa Calder declines to attend the ceremony: Freedom should lead to amnesty after all these years and it doesn’t seem as though it were going to happen. Freedom means freedom for all.

Calder returns with Louisa to New York from Washington, D.C., where he has finalized the details for Mountains and Clouds, a monumental stabile and mobile for the Hart Senate Building, Washington, D.C.

Calder dies in New York City at the home of his daughter Mary.

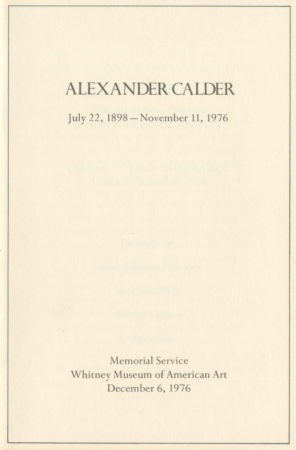

The Whitney Museum of American Art holds a memorial service. Officiating is director Tom Armstrong, with remarks by Sweeney, Saul Steinberg, cartoonist Robert Osborn, and Arthur Miller, and with a solo violin performance by Alexander Schneider.

Whitney Museum of American Art, New York. Alexander Calder: July 22, 1898–November 11, 1976, Memorial Service. Memorial program. 1976.

Sandy would not want moralizing about his life. But there is no way to avoid mentioning one aspect of his character. He was not a judgmental man—not at all. I do not know of a couple who had friends of such a wide variety of opinion and conviction. He, like Louisa, was nevertheless committed and it expressed itself sometimes in their public statements on the Vietnam War and other issues. But important as these were, they symbolized the real commitment that I have always thought was to simple decency. There was something noble in them and in their house. Is it not a great thing for us all, his gifts to us in a way that his personal qualities of directness, cheerfulness, his wit, and his joy in being alive should also have been so infused in his art? Like some playful Pantagruel he has dropped his monuments into the center of a hundred cities and his mobiles float above our heads like flocks of birds, things to catch light, to flutter with the wind, to arrest the rain and they are all Sandy saying in a thousand ways, “Yes and Yes and Yes.” Read more