Featured Text

Comment réaliser l’art ?

Abstraction-Création, Art Non Figuratif, no. 1 (1932). Translation courtesy Calder Foundation, New York.

Abstraction-Création, Art Non Figuratif, no. 1 (1932). Translation courtesy Calder Foundation, New York.

Comment réaliser l’art ?

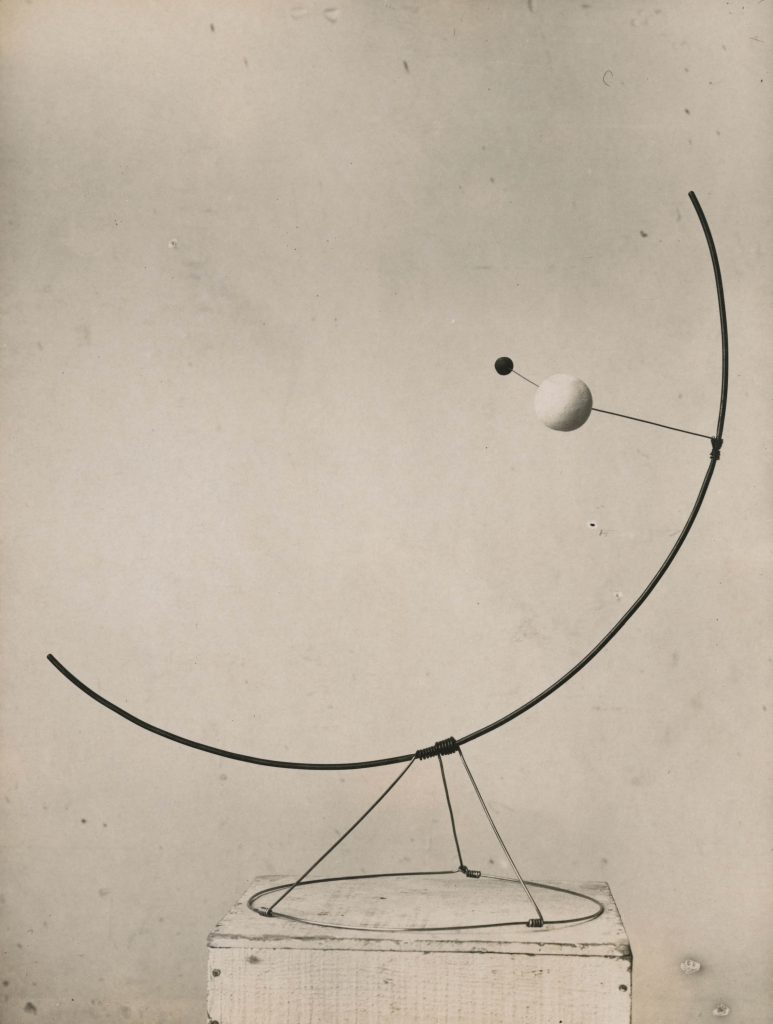

Des masses, des directions, des espaces limités dans le grand espace, l’univers.

Des masses différentes, légères, lourdes, moyennes,—indiquées par des variations de grandeur ou de couleur—des directions—vecteurs représentant vitesses, vélocités, accélérations, forces, etc …—ces directions faisant entre elles des angles significatifs, et des sens, définissant ensemble une grande résultante ou plusieurs.

Des espaces, des volumes, suggérés par les moindres moyens opposés à leur masse, ou même les contenant, juxtaposés, percés par des vecteurs, traversés par des vitesses.

Rien de tout ça fixe.

Chaque élément pouvant bouger, remuer, osciller, aller et venir dans ses relations avec les autres éléments de son univers.

Que ce soit, non seulement un instant “momentané,” mais une loi physique de variation entre les événements de la vie.

Pas d’extrations,

Des abstractions

Des abstractions qui ne ressemblent à rien de la vie, sauf par leur manière de réagir.

How can art be realized?

Out of volumes, motion, spaces bounded by the great space, the universe.

Out of different masses, light, heavy, middling—indicated by variations of size or color—directional lines—vectors which represent speeds, velocities, accelerations, forces, etc … —these directions making between them meaningful angles, and senses, together defining one big conclusion or many.

Spaces, volumes, suggested by the smallest means in contrast to their mass, or even including them, juxtaposed, pierced by vectors, crossed by speeds.

Nothing at all of this is fixed.

Each element able to move, to stir, to oscillate, to come and go in its relationships with the other elements in its universe.

It must not be just a “fleeting” moment, but a physical bond between the varying events in life.

Not extractions,

But abstractions

Abstractions that are like nothing in life except in their manner of reacting.

“Objects to Art Being Static, So He Keeps It in Motion.” New York World-Telegram, 11 June 1932.

NewspaperCalder, Alexander. “Que ça bouge—À propos des sculptures mobiles.” Manuscript, 8 March 1932. Calder Foundation, New York.

Unpublished Document or ManuscriptBerkshire Museum, Pittsfield, Massachusetts. Modern Painting and Sculpture: Alexander Calder, George L.K. Morris, Calvert Coggeshall, Alma de Gersdorff Morgan. Exhibition catalogue. 1933.

Alexander Calder, Statement

Group Exhibition CatalogueCalder, Alexander. “Un ‘Mobile.’” Abstraction-Création, Art Non Figuratif, no. 2 (1933).

MagazineFollowing a visit in October of 1930 to Mondrian’s studio, where he was impressed by the environment and actuation of space, Calder made his first wholly abstract compositions and developed the kinetic sculpture now known as the mobile. Coined for these works by Marcel Duchamp in 1931, the word “mobile” refers to both “motion” and “motive” in French. He also created stationary abstract works that Jean Arp dubbed “stabiles.”