The popular acceptance of Alexander Calder’s work can be partially attributed to its accessibility. This accessibility has, perhaps, given rise to an overly simplified understanding of his art, which in turn has minimized his intellectual achievement. One aspect of this simplification is explored here in an examination of the way in which Calder titled his works.

For Calder, titles were simply a way to easily differentiate one piece from the next: “A title is just like the license plate on the back of a car. You use it to say which one you’re talking about.”[1] Many of the titles assigned during the nineteen-forties even resembled the system used on license plates. The title 1R-4N-XW describes, in Calder’s particular short-hand mix of algebraic notation with English and French color names, a mobile with one red, four black (noir) and an open number of white elements. This system ended when the quantity of sculptures increased and it became difficult to recall a specific work based upon these codes.

Calder then shifted to titles of relation derived from some aspect of the artwork, a pertinent location, a person’s name or some other association. These titles were extemporaneous; a candid example of Calder’s impromptu manner can be seen in the film Calder, un portrait[2] wherein Calder is titling pieces while they are being registered at the Galerie Maeght in 1968. However, these relational titles can be a handicap to aesthetic observation, interpretation and appreciation if they are used as a guide for comprehending the work. Unlike some artists who imbue their art with insightful titles, Calder was not concerned with explanations. He did not intend his titles to be used as keys for interpretation; rather he wanted people to commune directly with an object, to appreciate it or not.

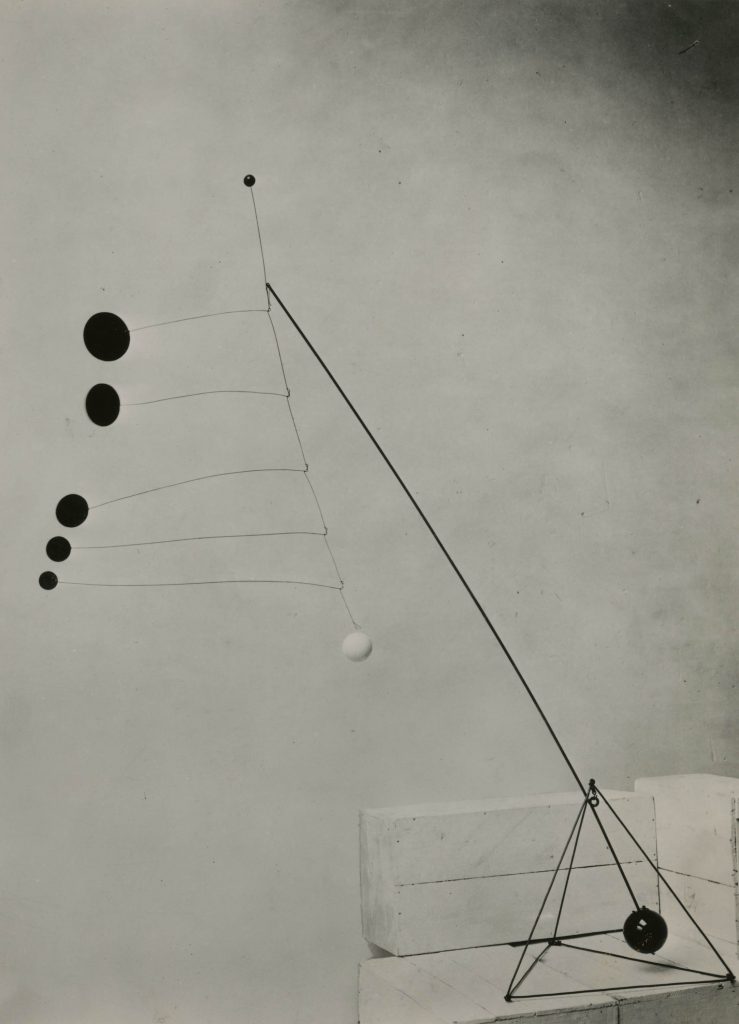

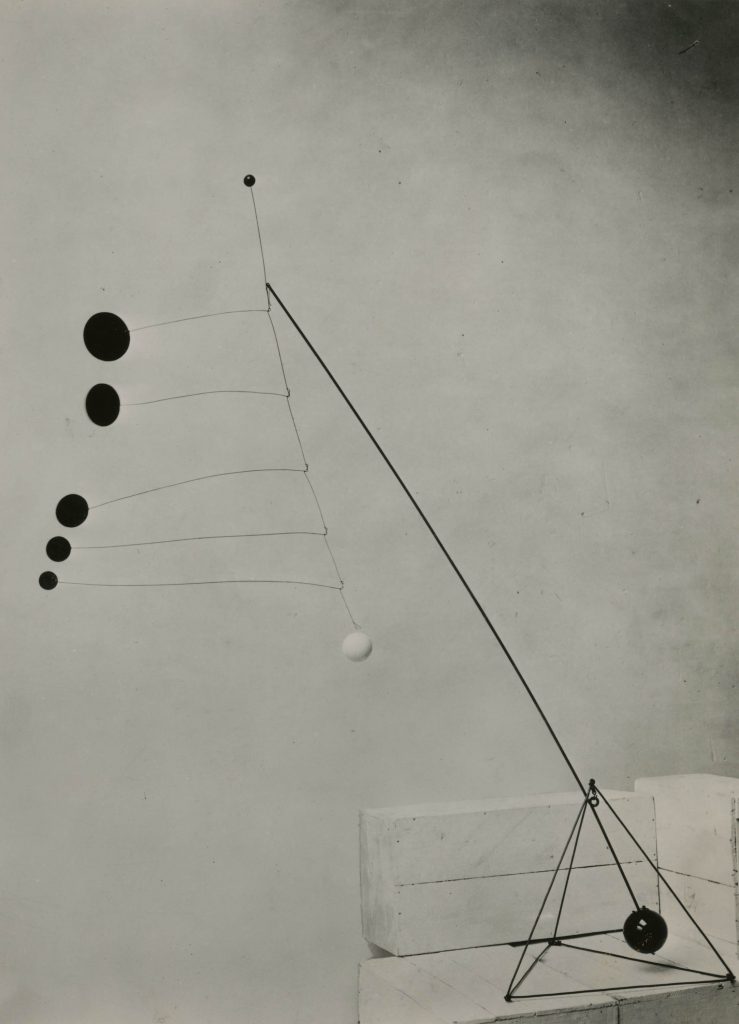

Even the terms now used to describe his pieces are alterations from Calder’s general word “object” which he used so “a guy can’t come along and say, no, those aren’t sculptures. It washes my hands of having to defend them!”[3] These alterations can be traced to the fall of 1931 when Marcel Duchamp was brought to Calder’s Paris studio,[4] by Duchamp’s companion Mary Reynolds. Duchamp was impressed with one of Calder’s first motorized sculptures. At Calder’s prompting Duchamp ventured the word “mobile” for this kind of sculpture, which in French refers to motion but can also mean the underlying motive. Calder was very pleased by this suggestion. Duchamp arranged with Marie Cuttoli that these works would be shown at her Galerie Vignon in February, 1932, and he suggested a design for the announcement card and the show title Calder: ses mobiles. Upon seeing the exhibition, Jean (Hans) Arp contributed the word “stabiles” to Calder’s first abstract sculptures shown the previous year at Galerie Percier.[5] During World War II Calder’s materials were limited, having been reserved for the war effort.[6] He returned to wood carving, making abstract elements for the new wood-and-steel-wire constructions that would be shown in 1943 for his last exhibition with Pierre Matisse. Duchamp together with the curator James Johnson Sweeney, who was organizing the Calder retrospective at The Museum of Modern Art that same year, devised the word “constellations” for these objects.

The following examples illustrate Calder’s simplicity of method and show how the significance of a title can be unrelated to the work itself:

Calder had a great affection for word play, especially bi-lingual puns and double entendres. When a secretary at Galerie Maeght, who was making a list for Calder of newly registered gouaches from 1974, typed Sans Francisco instead of San Francisco he was amused by the error and told her to leave it that way. Even when his first daughter was born in 1935 he “wanted to call her Rana, which in Scandinavian means ‘goddess’ and in Spanish ‘frog.’”[7]

In 1959 Calder’s friend Peter Bellew, director of the Section des arts plastiques, UNESCO, wanted to give a mobile with fifty elements to his wife Ellen for her fiftieth birthday. Bellew went to visit Calder at his home in Saché and found a marvelous piece in the studio that had only thirty-seven elements; Calder promptly titled the piece 37=50.

Calder located an ironworks, Etablissements Biémont, near his home in France that could fabricate huge steel sculptures under his direction. One of the pieces produced with Biémont in 1963 was Tamanoir (Anteater), of which Calder said, “The title of this … was just some vague association. After I had finished it and walked around it, it began to look like an anteater. On this business of titles, sometimes it’s the whole thing that suggests a title to me, sometimes it’s just a detail.”[8] Another piece made at Biémont during that same year was later purchased as a gift for Lincoln Center for the Performing Arts in New York by patrons Howard and Jean Lipman. This sculpture was unnamed until it was chosen for its new home in 1965. In this instance, the association with the location defined the title for Calder; he called it Le Guichet (The Ticket Window). In an effort to subvert an obvious interpretation he said: “I don’t like that name. I only called it that to identify it.”[9]

Commissioned to make a sculpture for the Lycée Jean Bart in Grenoble in 1967, Calder constructed a black stabile 26 feet high thickly encrusted with sharp triangles. In another example of location association, Calder gave it the humorous title Monsieur Loyal (Ringmaster), due to its central position between three areas occupied by the school building, a track field and a playground.

Throughout his career Calder switched or modified titles of his works. These fluctuations indicate Calder’s indifference in expressing something about a work through its title. His original title usually identified a work by its physical characteristics; the later title was often sentimentally descriptive, therefore more approachable.

Calder first met Sweeney in June 1933, when Sweeney came to see the exhibition Arp, Calder, Miró, Pevsner, Hélion, and Seligmann in Paris at the Galerie Pierre. The following year, Calder was to have his first exhibition with the Pierre Matisse Gallery in New York. Sweeney agreed to write an introduction for the catalogue and Calder offered him a sculpture from the show as a gift. Sweeney chose[10] the earliest piece exhibited, Object with Red Discs, a standing mobile made in Paris in 1932 that had been in the show at Galerie Pierre. The Sweeney family enjoyed the object immensely and Sweeney’s brother, John, dubbed it Calderberry Bush. This grafted title, which superseded Object with Red Discs in all subsequent references, was accepted by Calder. With this new title it becomes impossible to differentiate the non-objective red discs from berries, fixing the audience to a set viewpoint.

Following a suggestion from his friend, the architect Wallace K. Harrison, to construct sculptures in cast concrete, Calder decided to try modeling in plaster again, a technique he had not used since 1930. These plaster sculptures and casts in bronze, made during the summer of 1944, were shown that November in his first exhibition with Curt Valentin, at the Buchholz Gallery in New York. One of these works titled Still Life, consists of a three-legged platform with an abstract pierced triangular form above. In 1968 Perls Galleries engaged the Roman Bronze Works to cast, in editions of six, many of these sculptures from 1944 in preparation for a 1969 exhibition. Presumably because its original title had been forgotten, Still Life was retitled Chicken. Such a narrowly defined title cloaks the piece and directs the audience to interpret this abstract work as a hydrocephalic bird, the pierced triangular top element becoming the beak and eye. While its original title offers various richer interpretations, the new title trivializes the work.

During the winter of 1936–37, in his storefront studio in New York, Calder made a superb non-objective work from flat sheets of aluminum cut and shaped without preconception and assembled with copper rivets. He painted it flat black, effectively neutralizing the surface and allowing the form to dominate. It is an experiment in form, an engineered study of geometric possibilities. He simply titled this piece Stabile and exhibited it at the Pierre Matisse Gallery in February, 1937. Later (after 1955), while being inventoried at the Perls Galleries, this object was erroneously dated 1952 and renamed The Seal—a banal title for this impressive abstract work.

In 1957 the Port Authority of New York engaged Calder to make a sculpture to complement the vast arc of the new international arrivals building designed by Gordon Bunshaft of Skidmore, Owings & Merrill, under construction, at Idlewild International Airport in New York.[11] Titled .125, the thickness of the aluminum elements expressed in the decimal equivalent of an inch, this was Calder’s largest commission to date. After installing the mobile in the terminal Calder referred to it as Flight, a prosaic sobriquet derived from its location.

For the 1967 exposition (Expo ’67) in Canada, Calder was commissioned by the International Nickel Company to make a sculpture in unpainted stainless steel.[12] The theme of the exposition was “Man and his World.” He sent a maquette for a stable to Montreal: “In the beginning I called it Three Discs, but when I got over to Canada, they wanted to call it Man.”[13] Calder agreed to their request but later expressed concern about the sculpture being interpreted by way of its title. He insisted that the stabile did not represent anything specific.

Calder made a maquette of five aluminum sheets intersecting at divergent angles and spiking upwards and outwards at the Connecticut studio in 1964. He called this sculpture Object in Five Planes. It became represented by two monumental versions with divergent titles. The first enlarged example, eleven feet high, was completed the following year. In a hopeful gesture he donated this full-size stabile to the United States Mission to the United Nations in New York, and changes the title to Peace. The second enlarged version was commissioned by the Morris and Gwendolyn Cafritz Foundation as a gift for the National Museum of American Art, Smithsonian Institution, in Washington, D.C. Calder made this stabile thirty-five feet high, more than three times the size of Peace. He titled this new work Gwenfritz, an eponymous portmanteau; as “fritz” is an American slang term for coitus Calder was also displaying his characteristic naughtiness. At the dedication ceremony in 1968 Calder’s dealer Klaus Perls said he couldn’t use that double entendre, as it would offend the patron, so Calder announced that the title was Cafdolin, a switch utilizing the remaining parts of his patron’s name. This new title was a surprise to Gwendolyn Cafritz who insisted on the original title; it was switched back again to Gwenfritz.

It is evident to fully commune with Calder’s work the titles should not be taken as having much significance. In particular, the representational titles are apt to predetermine the viewer’s approach by unwittingly classifying the work, thus narrowing the viewer’s imaginative response and aesthetic experience. A more appropriate approach might be to examine a work before seeking out a name; to use the titles as insight to the artist himself, as a way to discover his predilections and sensibilities; then by this method the artwork is freed from the fixed relation imposed by its utilitarian or whimsically irrelevant title.

Hauser & Wirth, Los Angeles. Calder: Nonspace. Exhibition catalogue. 2019.

Andrew Berardini, The Cosmic Mathematics of Alexander Calder

Solo Exhibition CatalogueAlmine Rech Gallery, New York. Calder and Picasso. Exhibition catalogue. 2016.

Robert Slifkin, The Mobile Line

Susan Braeuer Dam, Liberating Lines

Jordana Mendelson, Picasso, Miró, and Calder at the 1937 Spanish Pavilion in Paris

Group Exhibition Catalogue“Calder in France.” Cahiers d’Art, no. 1 (2015). Edited by Alexander S. C. Rower.

Susan Braeuer Dam, Calder in France

Robert Melvin Rubin, An Architecture of Making: Saché and Roxbury

Agnès Varda in conversation with Joan Simon

Magazine, MonographMuseo Jumex, Mexico City. Calder: Discipline of the Dance. Exhibition catalogue. 2015.

Alexander S. C. Rower, Calder: Discipline of the Dance

Solo Exhibition Catalogue