From the outset, Alexander Calder’s imagination eclipsed that of avant-garde arbiters. Writing for Cahiers d’Art in 1933, Anatole Jakovski essentially conceded as much: “Art criticism is very often behind the times regarding creation, thus it hasn’t yet found the language that can correspond to the work of this American.”[1] Calder’s first Parisian sojourn began in the summer of 1926, just a month before his twenty-eighth birthday, and over the next seven years he forged a confounding sculptural vocabulary that continued to evolve for the rest of his life. Central to this evolution was his enduring kinship with France and its international bohemia, and at its core was his ability to assert an idiosyncratic vernacular, all the while enriching traditions and transcending boundaries. “He was an American speaking an international language, not a regional expression,” wrote James Johnson Sweeney, one of Calder’s most perceptive proponents. “Furthermore, he was an American not emulous of the accents of the boulevard. He was an American who spoke in his art with his own personal accent.”[2] From his early years in Paris to his later years in Saché in the Indre-et-Loire, Calder’s homegrown ingenuity thrived within his adopted France, giving rise to panoramic reverberations throughout his practice.

In a 1931 survey for Nord-Sud, Calder answered the prompt “Why I live in Paris” with, “Because here in Paris it is a compliment to be called crazy.”[3] Later in life, he recalled with less jocularity the difficulty of earning a living in 1920s New York. “Paris seemed the place to go, on all accounts of practically everyone who had been there, and I decided I would also like to go. My parents were favorable to this idea.”[4] Moving to Paris was something of a family tradition, and one that appealed to Calder, at that point an aspiring painter who had observed itinerant artists’ lives at close range. Calder’s grandfather, the sculptor Alexander Milne Calder, was drawn to Paris early in his career, as were Calder’s parents, the painter Nanette Lederer Calder and the sculptor Alexander Stirling Calder. Soon after Nanette and Stirling’s marriage in 1895 in Philadelphia, they settled into a studio on the Left Bank, where Calder’s older sister Margaret was born (nicknamed “Peggy from Paris”). Calder came along in 1898, after the Calders had returned to Philadelphia, and his childhood was equally peripatetic. In a 1930 letter to Peggy, Calder reflected, “It seems funny, when I stop to think about it—that I am living in the town where you were born, but which you have never really seen. It’s quite a grand town … Every phrenological feature of the terrain has something imposing, if not beautiful, and well placed and surrounded.”[5] Calder attuned himself to the cultural topography of Paris early on, enrolling in drawing classes at the Académie de la Grande Chaumière, exhibiting in salons, evincing social flexibility, and assuming the café habitué lifestyle.

It was in Calder’s first Paris studio at 22 rue Daguerre, just months after his arrival, that he began to explore the aesthetics of anticipation and action in Cirque Calder, 1926–31. While his affinity for the circus dated back to 1925, when he worked as an illustrator for the National Police Gazette, sketching the Ringling Brothers and Barnum & Bailey spectacle and marveling at the vast space of it all, what Calder produced in Paris was entirely unique. Featuring handcrafted figures and devices abstracted in wire and a variety of other quotidian materials (rubber, cork, cloth, leather, and wood, to name just a few), Cirque was a complex body of art brought to life by the artist. Over the ensuing years, Calder mounted numerous performances of his circus on both sides of the Atlantic, manipulating the figures to interact kinetically with one another; although he guided these performances, they were grounded in improvisation, giving the performers themselves what Sweeney later called “a living quality in their uncertainty.”[6] In this way, Cirque evinced the spectacle of a real-life circus and transcended the status of a replica. It also catapulted Calder into the Parisian vanguard, drawing an audience that included Jean Cocteau, Le Corbusier, Theo van Doesburg, Frederick Kiesler, Fernand Léger, and Piet Mondrian. Specialized critics such as Legrand-Chabrier reviewed Cirque with fervor: “A stroke of the brush, a stroke of the knife, of this, of that; these are the skillful marks that reconstruct the individuals that we see at the circus…. All of this is arranged and balanced according to the laws of physics in action so that it allows for the miracles of circus acrobatics.”[7] Calder, who had earned a degree in mechanical engineering from Stevens Institute of Technology in 1919, also professed an awareness of the “close alliance between physics and aesthetics,” a relationship that progressed rapidly in his art throughout his Paris years.[8]

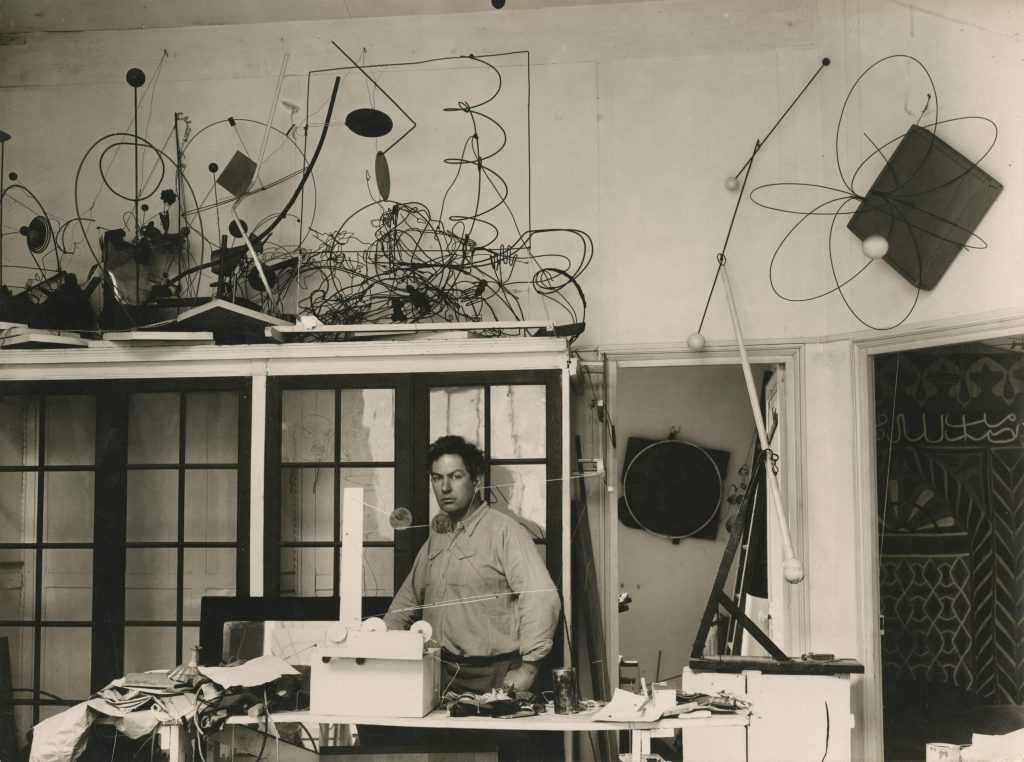

Concurrent with the development of Cirque, Calder made his first formal figures in wire, an evocative material he had used since childhood, with Josephine Baker I, 1926, and Struttin’ His Stuff, 1926. What New York critics struggled to categorize as art, Parisians heralded as inventions, giving the objects precedence within his practice and eventually bestowing upon Calder the title of Le roi du fil de fer (King of Wire). By 1929, Calder had become so wildly popular that he was asked to appear in British Pathé’s documentary film Montparnasse—Where the Muses Hold Sway, for which he invited the celebrated artists’ model Kiki de Montparnasse to sit for him. At first glance, Calder’s investigations in wire of portraits, circus themes, and animals seemed to some “merely a very amusing stunt cleverly executed,” to use the words of their creator.[9] Yet in essence, these transparent volumes born from Calder’s intuitive craftsmanship are expressions of unbounded energies multiplied exponentially in real time. Through the movement of wire lines both implied and authentic (from gestural sprightliness to vibratory suspensions, trembling sensations, and actual moving parts), they activate not only the surrounding space but also the viewer’s evanescent perceptions. Around the time of his Pathé debut, Calder began to endow his wire figures with more abstract qualities, providing only a framework drawn in wire and bringing the void to the fore.

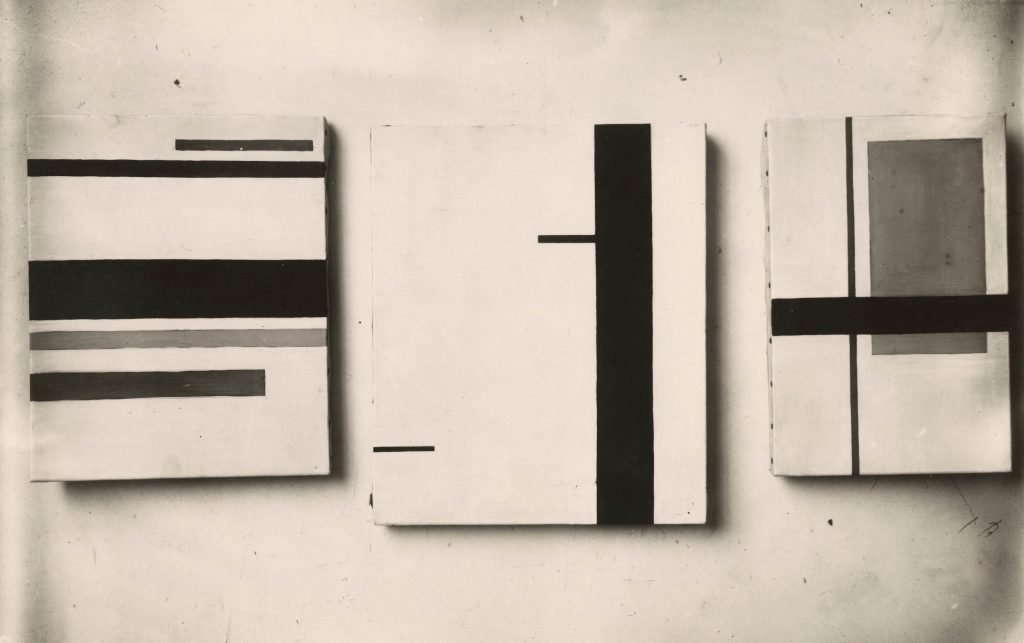

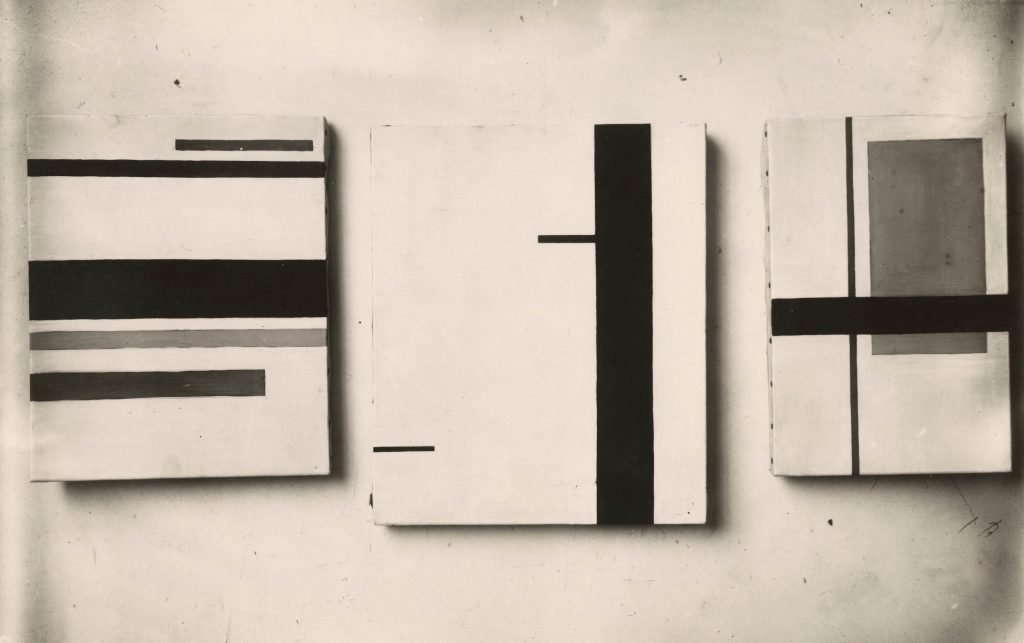

“It was a beautiful room, with light coming from both sides … I must have missed a lot, because it was all one big decor, and the things in the forground [sic] were lost against the things behind.” So began one of Calder’s many descriptions of Mondrian’s studio at 26 rue du Départ, which he visited in October 1930 at the prodding of artist William “Binks” Einstein just days after Mondrian attended a performance of Cirque at Calder’s Villa Brune studio. Calder continued, “But behind all was the wall running from one window to the other and at a certain spot Mondrian had tacked on it rectangles of the primary colors, and black, gray and white. In fact there were several whites, some shiny some matte. This caught my attention, and somehow I thought it would be nice if these rectangles oscillated.”[10] To this suggestion, the father of Neo-Plasticism austerely replied, “No, it is not necessary, my painting is already very fast.”[11] Calder avowed that he was “shocked” into abstraction by this studio, where he was impressed not only by the potential motion of the rectangular cardboard stunts positioned on the wall for compositional experimentation, but also by the seemingly transparent depth of the space, suffused with radiant energy. It was not Mondrian’s modern paintings that affected Calder—an unfortunate misconception that has been perpetuated over time—but rather the actuation of the space itself. Moreover, while the experience spurred Calder’s transition into abstraction, it was a nuanced shift at best, merely an awakening to a language for which he was already honing a singular dialect. Over the two weeks following the visit, Calder made nineteen abstract oil paintings, two-dimensional experiments that quickly developed into three- and four-dimensional ones.

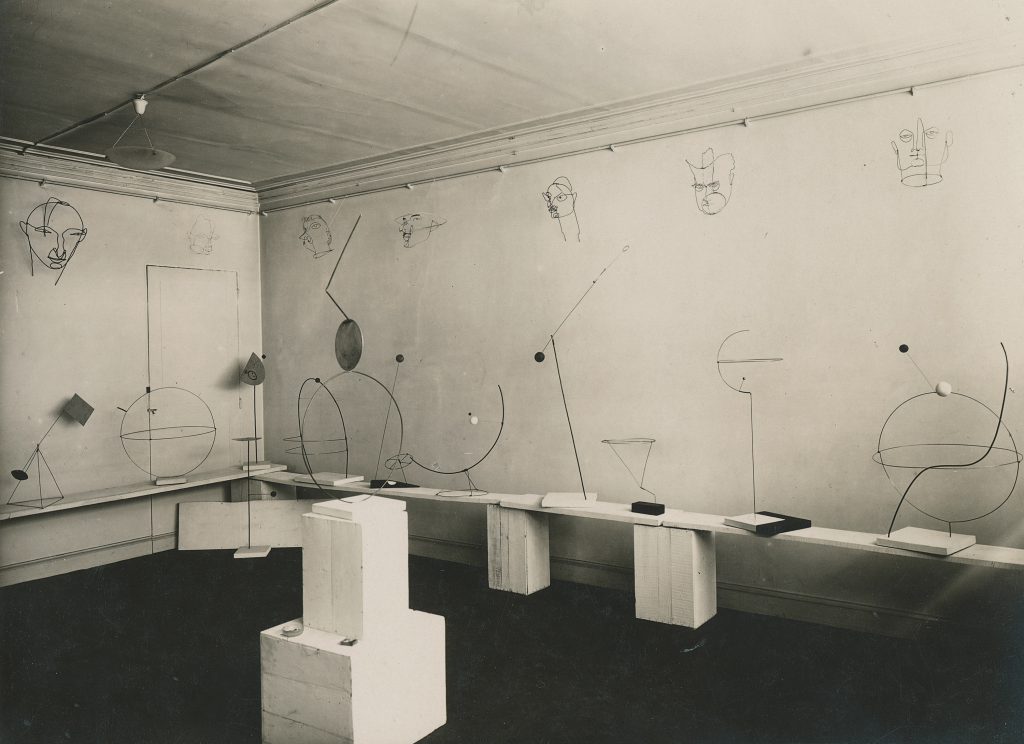

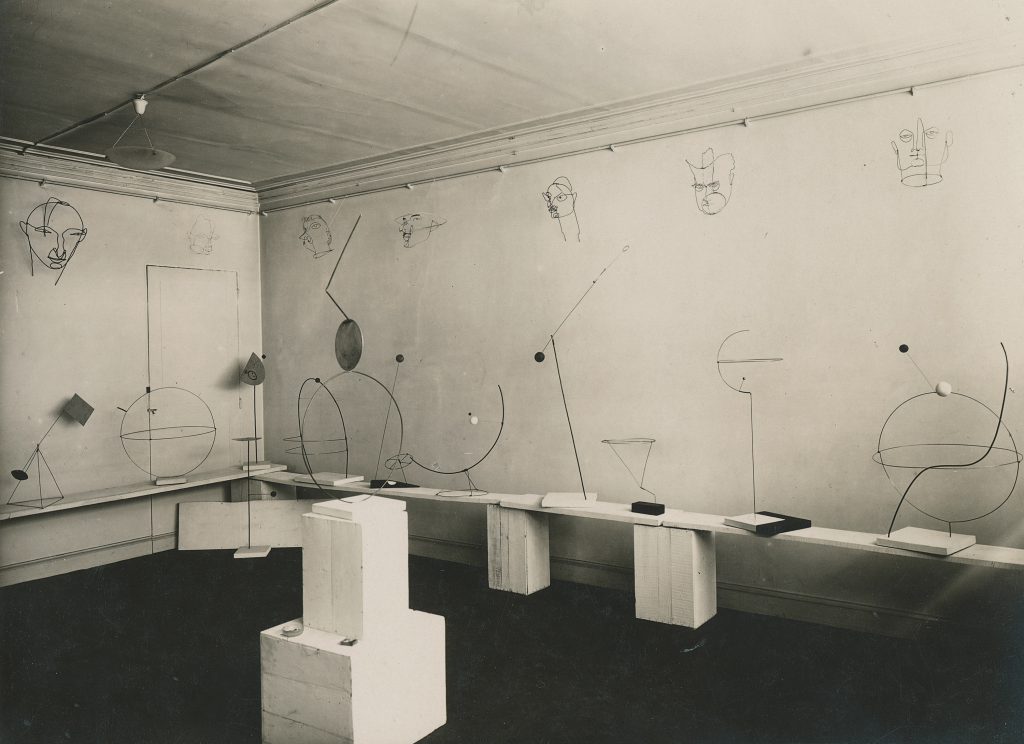

As Sweeney discerned in the 1940s, “Vernacular is the spice of poetry.”[12] Hardly anywhere is this notion more befitting than in Calder’s first nonobjective objects in wire, repurposed wood, and unpainted bits of tin and brass, elements capable of vibrantly catching and holding the surrounding light, which he made following his fabled moment at Mondrian’s studio. With their arrangements of arcs and their variations on representations of spheres, these compositions evoke imponderable interrelationships of energies. As the artist wrote in retrospect, “For though the lightness of a pierced or serrated solid or surface is extremely interesting the still greater lack of weight of deployed nuclei is much more so. I say nuclei, for to me whatever sphere, or other form, I use in these constructions does not necessarily mean a body of that size, shape or color, but may mean a more minute system of bodies, an atmospheric condition, or even a void.”[13] At their first showing, in the spring of 1931 at Galerie Percier, Paris, in “Alexandre Calder: Volumes–Vecteurs–Densités/Dessins–Portraits,” these works were lined along the wall on humble planks placed on upright champagne boxes. Installed high above them were wire portraits of personalities such as Léger, de Montparnasse, Amédée Ozenfant, and Edgard Varèse; by this point, Calder had dismissed these otherwise celebrated objects, even apologizing for their inclusion at Percier.[14] The exhibition had been arranged through Calder’s friends in Abstraction-Création, a group that he would join that summer whose members included Jean Arp, Robert Delaunay, Jean Hélion, Mondrian, and Antoine Pevsner. Léger wrote the introduction to the catalogue, highlighting the common vitality between two extremes: this American artist and the leading lights of the Parisian avant-garde.

Eric Satie illustrated by Calder. Why not?

“It’s serious without seeming to be.”

Neoplastician from the start, he believed in the absolute of two colored rectangles …

His need for fantasy broke the connection; he started to “play” with his materials: wood, plaster, iron wire, especially iron wire … time both picturesque and spirited …

A reaction; the wire stretches, becomes rigid, geometrical—pure plastic—it is the present era—an anti-Romantic impulse dominated by the problem of equilibrium.

Looking at these new works—transparent, objective, exact—I think of Satie, Mondrian, Marcel Duchamp, Brancusi, Arp—those unchallenged masters of unexpressed and silent beauty. Calder is of the same line.

He is 100 percent American.

Satie and Duchamp are 100 percent French.

And yet, we meet?[15]

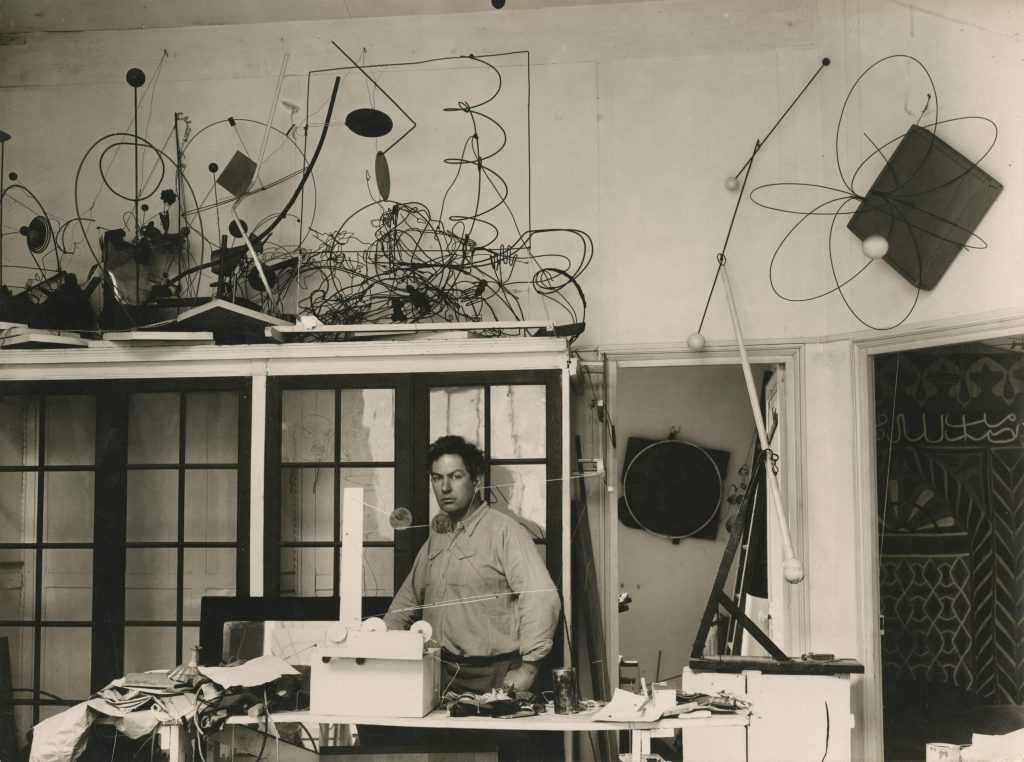

“To me,” Calder wrote, “the most important thing in composition is disparity.”[16] In his Paris studio at 14 rue de la Colonie, just months after his Percier exhibition brought him fame, Calder set sculpture in motion using motors and cranks to diversify the spatial relationships of compositional elements. Mesmerized by the innovations during a visit to Calder’s studio that autumn, Duchamp suggested the appellation “mobile,” a pun in French that means both “that which moves” and “motive.” In his mobiles, which would come to move by the vagaries of air, Calder engaged not only disparities of movement, color, size, shape, and sound but also thresholds between positive and negative space, and material and immaterial phenomena; the resulting works are experiential compositions that transcend both the apparent and the subliminal dialects of nature. Describing one of his earliest motorized works, severely abstract in its constitution, Calder said, “This has no utility and no meaning. It is simply beautiful. It has a great emotional effect if you understand it. Of course if it meant anything it would be easier to understand, but it would not be worth while.”[17] With these abstractions, Calder challenged viewers to leave aside their preconceptions and engage in an unmediated experience, to commune directly with an object in the shared space of the present. By 1933, Calder premiered Small Sphere and Heavy Sphere, 1932/33, to Paris audiences at Galerie Pierre Colle. The first mobile suspended from the ceiling, it involved a lumbering iron sphere and a small wooden sphere that would strike at unpredictable moments the various impedimenta of discarded glass bottles, a wooden box, a tin can, and a gong arranged on the floor by the viewer, who also activated the ensemble by setting the spheres in motion. Considered at once a chance composition, a sound sculpture, and an act of ingenious recycling, Small Sphere and Heavy Sphere was revolutionary, prompting Cahiers d’Art to proclaim: “In France, Calder is the promoter of art in motion. His exhibition at Galerie Colle several weeks ago convinced the most incredulous of the possibility of kinetic sculpture.”[18]

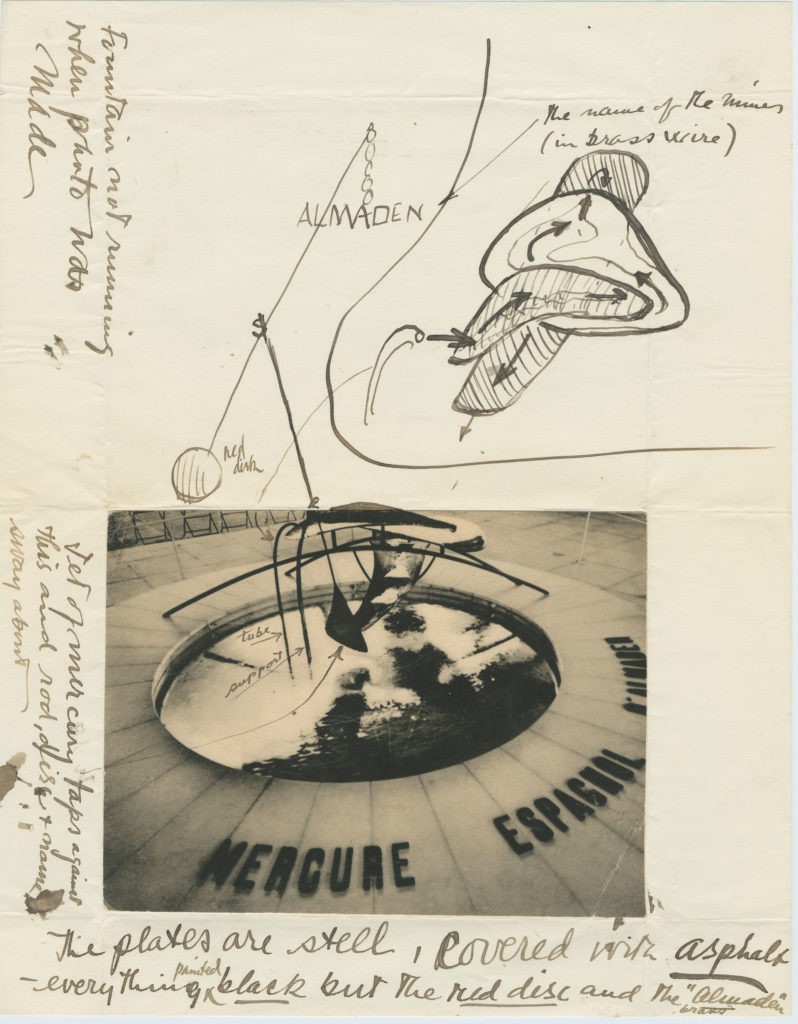

In the summer of 1933, Calder and his wife, Louisa, moved back to the States, in part due to political upheavals in Europe and also with the desire to start a family. The move was a reluctant one, not only for Calder but also for Louisa, who had spent part of her childhood in France and whose great-uncle Henry James had been such a trenchant interpreter of the American experience in Europe. Yet Calder’s presence endured in Paris through a number of means, among them the art publishers Christian and Yvonne Zervos. Beginning in the 1930s, their journal Cahiers d’Art featured some of the earliest photographic depictions of Calder’s objects in motion by Marc Vaux, as well as images by Swiss photographer and graphic designer Herbert Matter. Appearing in its 1937 issue dedicated to the Paris International Exposition were photographs by Hugo Herdeg of Calder’s Mercury Fountain, 1937, installed alongside Picasso’s Guernica in the Spanish pavilion, with its mercury mined from Almadén to symbolize Republican resistance to Franco’s fascism.[19] “In the old days you were Wire King, now you are Father Mercury,” Léger told Calder at the unveiling of this politically charged work.[20] The commission had come about through Joan Miró’s introduction of Calder to the pavilion’s architects, Luis Lacasa and Josep Lluís Sert, during Calder’s 1937 sojourn in France, which was prompted by discussions of a possible exhibition at Galerie des Cahiers d’Art. Although the latter show was postponed due to the Zervoses’ preoccupation with other projects, Calder was included in “Origines et développement de l’art international indépendant” for the Musée du Jeu de Paume, spearheaded in part by Christian and Yvonne. Following on the heels of Alfred H. Barr, Jr.’s 1936 “Cubism and Abstract Art” at the Museum of Modern Art in New York, which classified Calder with forward-thinking artists such as Hélion, Alberto Giacometti, Henry Moore, and Ben Nicholson, the seminal exhibition opened in July 1937; after a rather complicated curatorial process, Calder’s sculpture found a place in the garden.[21] Throughout their stay in France, which would mark the last time they visited Europe until the war’s end, the Calders rented houses in Paris at 80 boulevard Arago and in Varengeville-sur-Mer, near two friends of theirs, the architect Paul Nelson and his wife Francine, outfitting the garages in both places to serve as Calder’s studios.

Even during Calder’s absence from Europe surrounding the war years, his affinity with France flourished from afar. In September 1933, the Calders bought an eighteenth-century farmhouse in Roxbury, Connecticut, in a county already inhabited by erstwhile American expats returned from Paris, including the writers Robert Coates, Malcolm Cowley, and Matthew Josephson, who in turn welcomed Calder with open arms. Later, through Paul Nelson, Calder became involved with the Washington, DC, chapter of France Forever (the Fighting French Committee in the United States, a group that cooperated with the French Committee of National Liberation), exhibiting for the organization in a 1942 group show and a 1944 solo one, for which he gave two performances of Cirque. Calder also wrote pleas on behalf of European friends seeking asylum in the States, and he encouraged André Masson and Yves Tanguy to relocate to Connecticut. Along with Marc Chagall, Arshile Gorky, David Hare, and Hans Richter, these artists resided near Calder’s Roxbury home in Litchfield County, and Calder often hosted Surrealist exiles, among them André Breton. Calder was especially pivotal in assuaging Masson’s displacement. Attesting to the profundity of their friendship is Masson’s 1942 poem “L’atelier d’Alexander Calder,” which was later published in Cahiers d’Art.[22]

In June 1946, eager to return to Paris, Calder took his first transatlantic flight to prepare for his debut postwar exhibition at Galerie Louis Carré. The project had been gestating since the summer of 1945 through the collaborative efforts of Duchamp, who conceived of the show, and Jean-Paul Sartre, who wrote an essay for the catalogue. “Alexander Calder: Mobiles, Stabiles, Constellations” procured immediate and lasting renown. What have gone largely unrecognized, however, are Christian Zervos’s concurrent endeavors on behalf of the artist for his postwar entrée. Following the advice of his friend Henri Seyrig, Calder initially consulted with Zervos about an exhibition as early as May 1945.[23] In a follow-up letter to Seyrig, Zervos proposed a show at Galerie Mai or Galerie Drouin, further intimating his enthusiasm for the artist: “I hasten to tell you of all of my admiration for Calder and for his work…. He would bring us a bit of youth and joy, that which we’re lacking most here, because the years of occupation were years of slow death for this country. There’s no longer a spirit of youth or a spirit of enterprise amongst the people or the others. We’re doing everything that we can to wake ourselves up, but it’s very difficult.”[24]

Although plans for a Zervos-organized exhibition were trumped for a time by Carré’s demands for exclusivity, Christian and Yvonne’s eager commitment to Calder continued undiminished in myriad ways.[25] Circulation of Cahiers d’Art was suspended from 1941 to 1943, but in its substantial 1945–46 issue alone, two articles were published on Calder; one was Gabrielle Buffet’s “Sandy Calder, forgeron lunaire,” which ran supplemented with numerous photographs, including images of Calder’s 1943 retrospective at the Museum of Modern Art in New York; the other was Georges Mounin’s “L’objet de Calder.”[26] Printed alongside Mounin’s text was an image of a hanging mobile, one of many gifts from Calder to the Zervoses over the course of their long-standing friendship. When asked to lend the mobile to a show in 1949, Christian Zervos declined; one of the reasons was, as he intimated to Calder, “When I work, and I work all the time, I keep a company all the more pleasant because it brings me nothing but pleasure, which is not the case with men.”[27] Correspondence between the Zervoses and Calder was by turns sentimental, professional, and humorous, written around both workaday and life-changing events.

Particularly noteworthy in the Zervos-Calder relationship is the artist’s inclusion in the 1947 “Exposition de peintures et sculptures contemporaines” at the Palais des Papes, Avignon, organized by Yvonne Zervos, Jacques Charpier, and René Girard. Majestically poised on a stone altar in the Gothic palace was Calder’s Explosive Object, 1944, a potentially galvanizing standing mobile. At its feet were works by Giacometti and Arp, and on the surrounding walls hung paintings by Chagall, Henri Matisse, and Pablo Picasso, with works by Paul Klee in the sacristy.[28] As Calder described, Explosive Object “has Surrealist potential. There are 9 plates and 8 sticks, a little fork and the foot. Everything is assembled according to its width. Once assembled, there is no longer a risk of it falling apart, but if you place your forefinger under the smallest one, ‘as if tickling it,’ and we raise it suddenly by raising the plate from the wire that holds it, then everything falls apart.”[29] Calder had originally proposed to lend Explosive Object to Breton and Duchamp’s “Exposition Internationale du Surréalisme,” held concurrently at Galerie Maeght. In its place he sent an exotic mobile with bits of glass, pottery, wood, and sheet metal, which was displayed alongside Gorky’s The Liver Is the Cock’s Comb, 1944, and Calder also contributed a lithograph to Duchamp and Enrico Donati’s “Le Surréalisme en 1947.”[30]

Less than five years after they began, Christian Zervos’s efforts for a Calder exhibition paid off with exciting reverberations. In the summer of 1949, Aimé Maeght wrote to Zervos, “Following our conversation, I’d like to confirm that I would be very willing to do an exhibition of recent works of Alexander Calder. Indeed, I consider him to be probably the most original sculptor in America at present and simply a great artist.”[31] In June of the following year, Galerie Maeght mounted Calder’s first solo show there, “Calder: Mobiles & Stabiles,” comprising over fifty works and instigating what would become an ongoing association between Calder and Maeght. As a result of the exhibition, the Musée National d’Art Moderne in Paris purchased Le 31 Janvier, 1950, becoming the first French institution to add a Calder to its collection, and in the following decade the museum mounted a landmark presentation of nearly 250 works in the wake of the artist’s 1964–65 retrospective at the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum in New York. “Finally the first of July, 1965, arrived and I was consecrated one hundred days—somewhat like Napoleon—by the Musée d’Art Moderne in Paris. I was quite touched to see an American flag by the tricolore over the avenue du Président Wilson,” remarked Calder, who went on to donate twenty-nine works to the institution, ranging from wire figures to large-scale sculptures.[32]

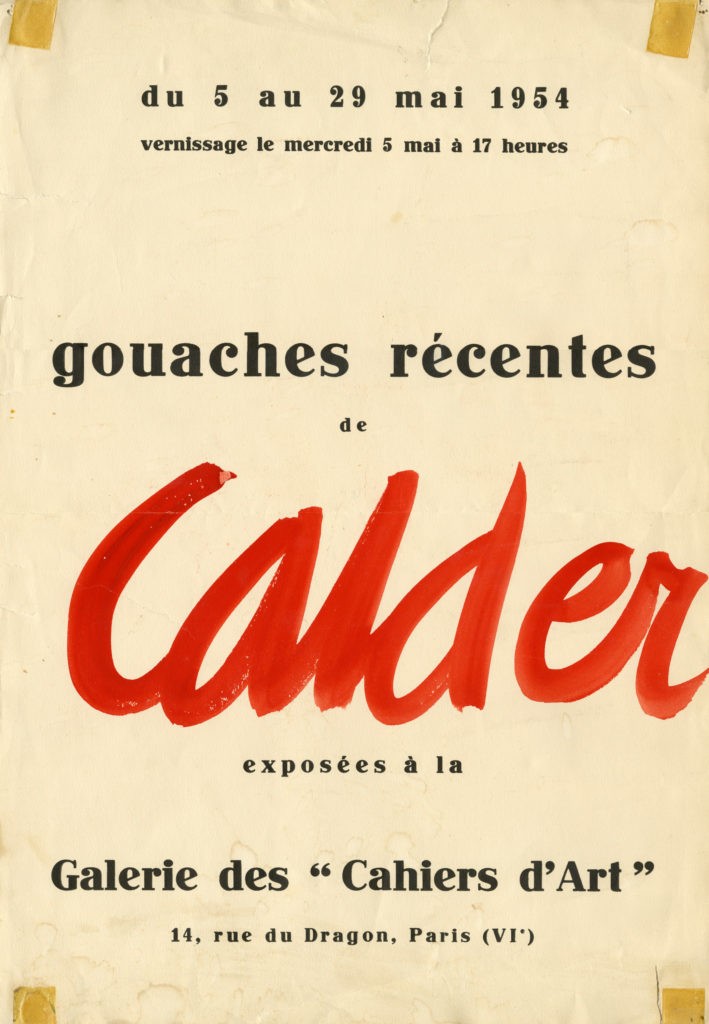

Since his first trip in 1926, Calder had considered France a second home, and in 1953 he recommitted to living and working there, beginning with a yearlong sojourn in Aix-en-Provence. Just as in Paris, his surroundings, this time bucolic, stimulated novel approaches. In July 1953 the Calders arrived in the hamlet of Les Granettes and rented a house, Mas des Roches, that had little running water and no electricity. In his new studio here, set up in the house’s carriage shed, Calder began working on gouaches. “I put in a little table and did gouaches there—many of them. When there was too much water, I would tilt the table and let it flow onto the ground. I would moisten the paper with a flow of water and wait till it dried a bit but not too much; then I would draw on it with a brush full of China ink—this would develop clouds and trees and fungi and things of that nature.” With their washes of color, these works brim with translucent, dynamic atmospheres that in a way reflect the artist’s own enthusiasm for the process. Calder concluded, “In addition to the watery variety, I did some large human heads with crosshatched stripes.”[33] Calder continued to work on his gouaches in Malvalat, his second home in Aix (this one with functioning amenities), where he established a studio on the third floor. In the spring of 1954, he premiered over a dozen of his recent gouaches at Galerie des Cahiers d’Art.

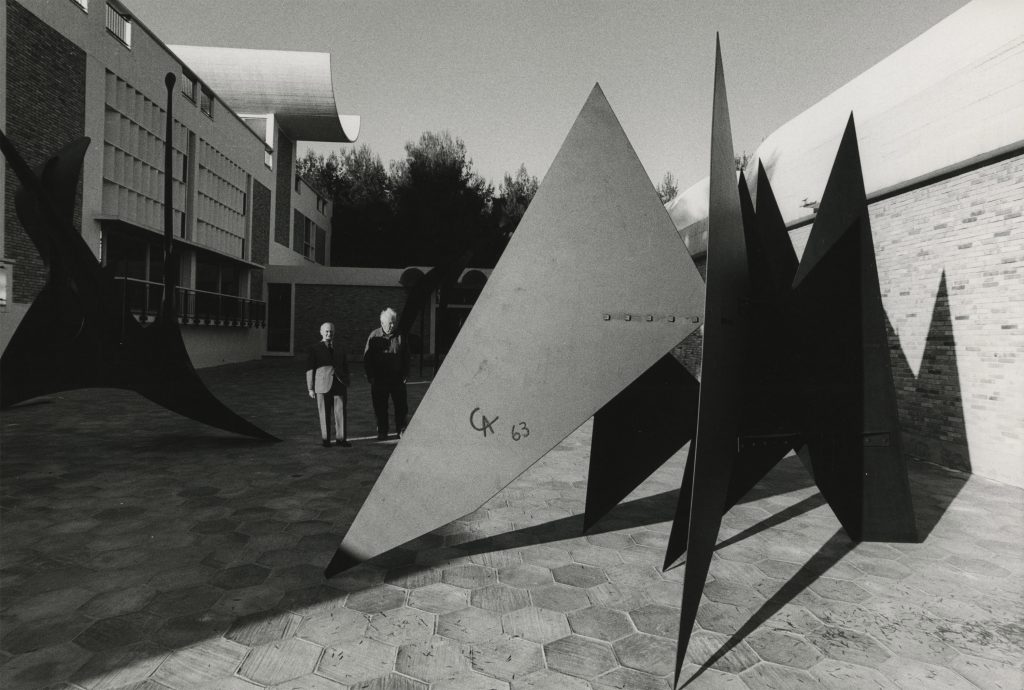

From the 1950s onward, Calder developed works of an ever-growing scale, many of them in France. At a blacksmith shop near Les Granettes in 1953, he created an important group of large-scale outdoor standing mobiles without commission, titled Yellow Disc, Les Granettes, L’Empennage, and Myxomatose. Executing with sheer aplomb in direct scale as opposed to enlarging from maquettes, Calder used chalk to draw shapes onto steel plates that he then cut and welded into configuration by torch. Later that autumn, the Calders visited their friend and future son-in-law Jean Davidson in Saché at his renovated mill house, Moulin Vert.[34] On his property they discovered an abandoned domicile, François Premier, which they acquired in exchange for three mobiles; Davidson’s renovations of François Premier were completed the following July, and a second building across the way became the artist’s “gouacherie.” In Saché, Calder worked with a blacksmith from nearby Azay-le-Rideau to make even more venturous sculptures than those made previously in Aix, among them Le Flamand, 1954, and an untitled piece from the same year, and in November he brought together many of his recent works from Aix, Saché, and Roxbury in an exhibition at Galerie Maeght, Paris.

In the spring of 1957, UNESCO’s Committee for Architecture and Works of Art invited Calder to create a sculpture for its Paris headquarters, which was being designed by Calder’s friend the architect Marcel Breuer, with Pier Luigi Nervi and Bernard Zehrfuss. Calder’s first public commission in France, Spirale, 1958, coincided with the development of two equally formidable projects, .125, 1957, for Idlewild Airport in New York (now John F. Kennedy International Airport) and The Whirling Ear, 1958, for the United States pavilion at the Brussels World’s Fair. Nearing thirty feet high, Spirale marked a major shift to monumentality, and it was installed for the building’s inauguration in August 1958. At the time of the commission, Calder did not yet have a foundry in France, so he fabricated the mobile top at Waterbury Ironworks in Connecticut, and he employed French industrial designer Jean Prouvé to make the base in France in order to spare transportation costs. In 1962, Calder began working with Establissements Biémont, a full-scale industrial ironworks in Tours, to assist him with the execution of his monumental sculptures, which were met with increasing international demand. In resonance with his early abstract works, these colossal titans engage a continuity of experience between aesthetics and nature as they slice through space without filling it up, sculpting the air that surrounds them, conjuring dynamism from absence. In the words of playwright Arthur Miller, who was Calder’s Roxbury neighbor, “Still, it is from the spaces, the silences in his works that life springs out at us.”[35]

Throughout the last decades of his life, notwithstanding his worldwide travels for commissions, exhibitions, and awards, Calder’s appreciation for the unpretentious ways of living in rural France increased, as did his presence there. In the summer of 1957, Calder and Louisa acquired a defunct customs house, Le Palud, located at the mouth of the Tréguier River in La Roche Jaune, Brittany, while visiting their friends Renée (Ritou) Nitzschke and André Bac. Calder designed and built a studio that he attached to the house, but with a separate entrance, and several times a year the high tide would engulf the surrounding lowland, making an island of the site. By 1963, Calder had completed the construction of a much larger hillside studio in Saché, and by 1970, a new house, Le Carroi, both of which he designed himself.

As a result of his abiding contributions to France, Calder was named Officier de la Légion d’Honneur in 1968; Commandeur de la Légion d’Honneur (1974); and Citoyen d’Honneur de la Commune in Saché (1974) (after which he donated his Totem-Saché, 1974, to the village); and he was awarded the Grand Prix National des Arts et des Lettres (1974).

At the age of seventy, Calder presented a retrospective at the Fondation Maeght in Saint-Paul-de-Vence, France, less than four years after his historic event at the Musée National d’Art Moderne in Paris. A grand display of over three hundred works spanning the artist’s career, the exhibition attracted crowds of visitors, among them Christian and Yvonne Zervos. As Christian wrote to Calder in April 1969, “Yvonne and I went to see your show at Fondation Maeght. We were enormously interested by the number and the great variety of the objects exhibited. This reminded me with much emotion of your beginnings in France…. I had many intense moments at the Fondation.”[36] Zervos’s letter, written a year and a half before his death, underscores the decades-long amity not only between the two luminaries but also between Calder’s native America and his adopted France. In Calder’s life, as in his art, they were contemporaneous features of his experience, of his voluminous mind’s eye.

Hauser & Wirth, Somerset, England. Calder: From the Stony River to the Sky. Exhibition catalogue. 2018.

Susan Braeuer Dam, For the Open Air

Jessica Holmes, More than Beautiful: Politics and Ritual in Calder’s Domestic Items

Solo Exhibition CatalogueAlmine Rech Gallery, New York. Calder and Picasso. Exhibition catalogue. 2016.

Robert Slifkin, The Mobile Line

Susan Braeuer Dam, Liberating Lines

Jordana Mendelson, Picasso, Miró, and Calder at the 1937 Spanish Pavilion in Paris

Group Exhibition Catalogue“Calder in France.” Cahiers d’Art, no. 1 (2015). Edited by Alexander S. C. Rower.

Susan Braeuer Dam, Calder in France

Robert Melvin Rubin, An Architecture of Making: Saché and Roxbury

Agnès Varda in conversation with Joan Simon

Magazine, MonographMusée Picasso, Paris. Calder-Picasso. Exhibition catalogue. 2019.

Bernard Ruiz-Picasso and Alexander S. C. Rower, Confronting the Void

Chus Martinez, No Feeling Is Final

Group Exhibition Catalogue