Over the past fifty years, we have integrated the experience of living with our grandfathers’ works in so many different professional and personal ways that it has become virtually impossible to make a distinction between the emotional and the intellectual, or what we feel and what we know. We have gained important insights into their work, regardless of bloodline, as anyone who observes works of art on a daily basis—and does so over the course of a lifetime—will have a unique perspective. If our perspective is privileged, it is also, for that very reason, particular.

Our recent investigation into the resonances between Calder and Picasso has caused us to return time and again to a key connection: the exploration of the void, or the absence of space, which both artists defined from the figure through to abstraction.[1] Examining the divergent yet resonant ways in which Calder and Picasso expressed the void-space in their work has made it possible for us to reevaluate not only the central practices of these two artists but also the overarching ambitions of twentieth-century modernity. Both artists wanted to present or represent nonspace, whether by giving definition to a subtraction of mass, as in Calder’s sculpture, or by expressing contortions of time, as in Picasso’s portraits. Calder externalized the void through curiosity and intellectual expansion, engaging unseen forces in ways that challenge dimensional limitations, or what he called “grandeur immense.” Picasso personalized the exploration, focusing on the emotional inner self. He brought himself inside each character and collapsed the interpersonal space between author and subject.

When we confront the many connections between Picasso and Calder, we find that we are engaging in nothing less than a discourse about modernity. We gain new insights into the artist’s encounter with the subject, the transformation of that subject into an artistic reality, and the audience’s engagement with that new reality. Marcel Duchamp, in a lecture he gave at the American Federation of the Arts convention in Houston in the spring of 1957, had this to say about the creative act:

To avoid a misunderstanding, we must remember that this ‘art coefficient’ is a personal expression of art ‘à l’état brut,’ that is, still in a raw state, which must be ‘refined’ as pure sugar from molasses, by the spectator; the digit of this coefficient has no bearing whatsoever on his verdict. The creative act takes another aspect when the spectator experiences the phenomenon of transmutation; through the change from inert matter into a work of art, an actual transubstantiation has taken place, and the role of the spectator is to determine the weight of the work on the esthetic scale. All in all, the creative act is not performed by the artist alone; the spectator brings the work in contact with the external world by deciphering and interpreting its inner qualifications and thus adds his contribution to the creative act. This becomes even more obvious when posterity gives its final verdict and sometimes rehabilitates forgotten artists.[2]

We believe that Picasso’s and Calder’s artistic achievements were shaped and reshaped by their explorations and exploitations of the void. We strive to understand how these two artists, each in his own very different ways, engaged with the void and all that it implies about a world where mass is unsettled by the absence of mass and where at the center of anything and everything what we discover is a vacuum.

BRP Even though my grandfather was seventeen years older than Calder, there is an extraordinary resonance between the two artists. Both of them were born at the tail end of the nineteenth century, both of their fathers were classically trained artists, and both had a deep respect for the circus arts. While it would be interesting to examine their oeuvres with these affinities in mind, that’s not what our project is about.

ASCR Exactly. And there are a number of other chronological connections, too. We know they crossed paths in July 1937 at the Spanish Pavilion at the Paris World’s Fair, where Calder’s Mercury Fountain was installed right in front of Picasso’s Guernica. Not long after, the Museum of Modern Art, New York, gave each of them a retrospective a matter of years apart: Picasso’s closed in January 1940, and Calder’s opened in September 1943. They were each featured prominently at the 2nd Bienal de Arte Moderna de São Paulo in 1953, and later that decade, they each received a commission for the UNESCO headquarters in Paris. But aligning their respective trajectories, or unraveling who was inspired by who, is not our aim. That would be a different project altogether, to be conceived of by others.

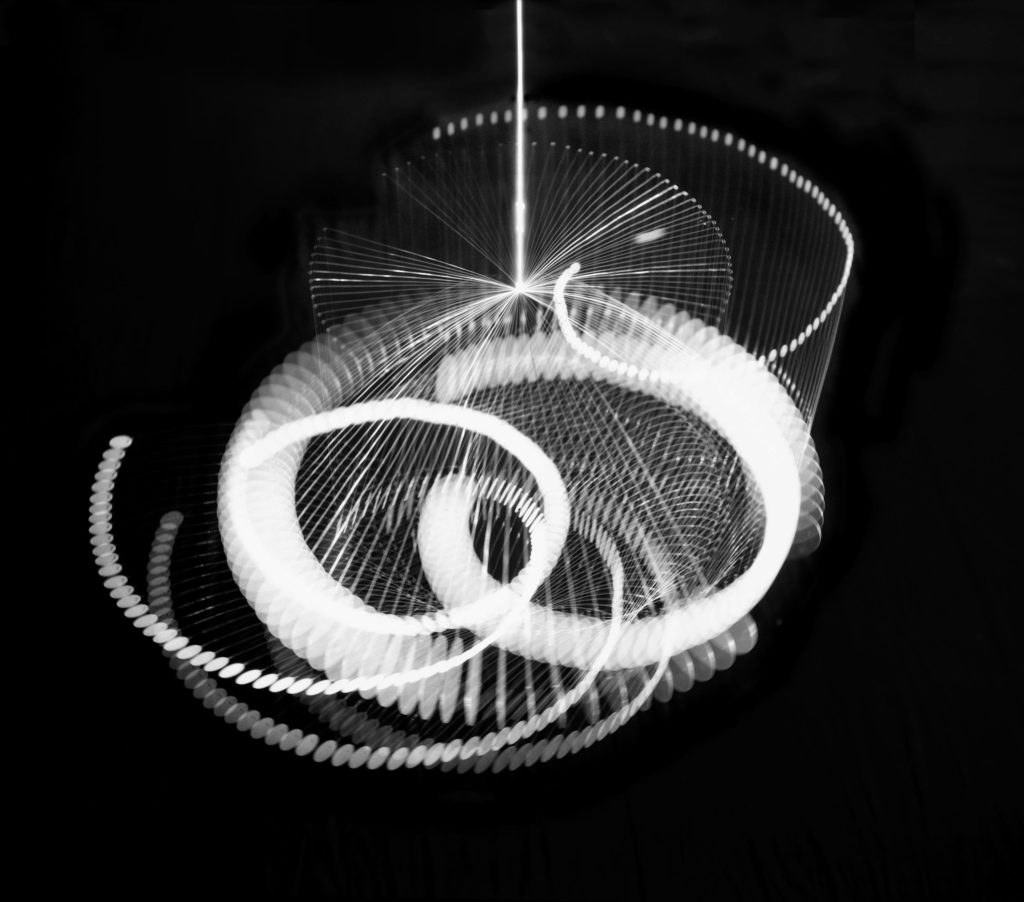

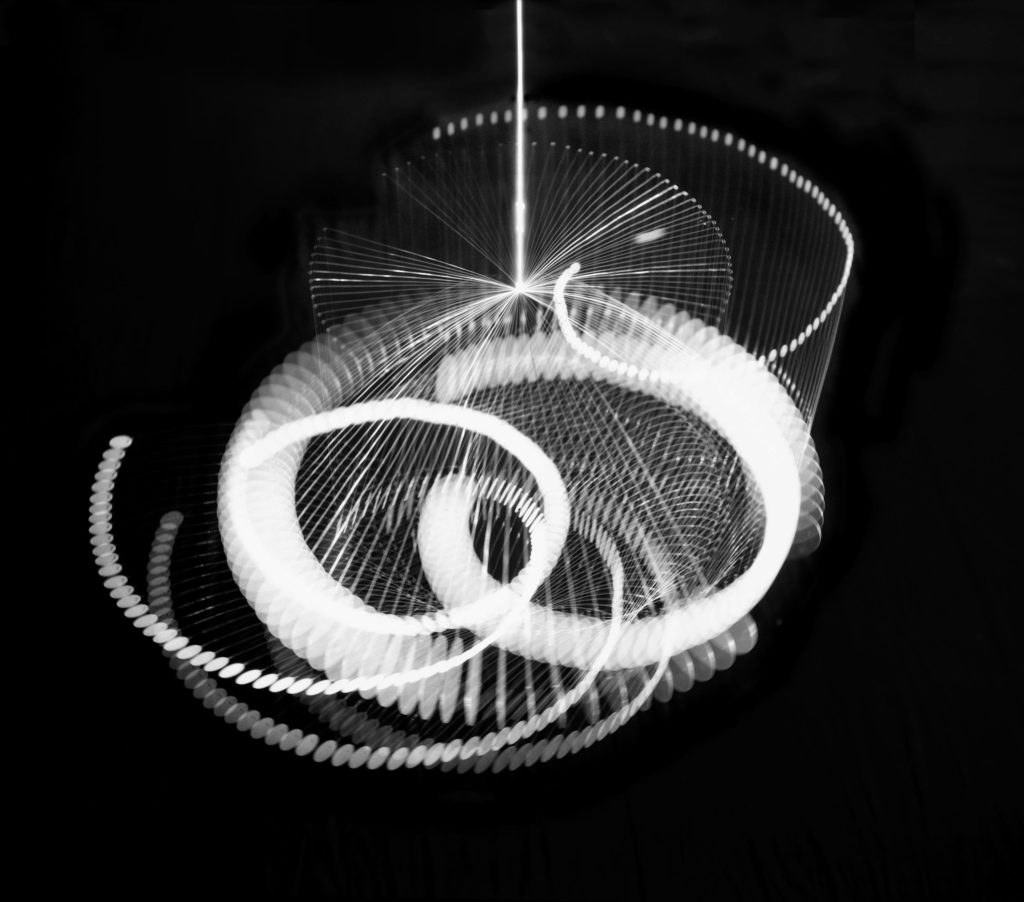

BRP What I find appealing in the iconic works of great artists is that with the first contact, which is indeed a true encounter, time stops for a few seconds: no references, no knowledge can interfere with what I am looking at. Instead of trying to observe from afar, I stop thinking. I am present to the precise moment of discovery; only then can I understand this moment of vacuum. As a mere beholder of the creative act on show, I end up filling the void with instantaneous emotion that absorbs my gaze. I observe these works of ancestral magnetism, and this creates new perceptions in me that words fail to describe. It’s at once ephemeral and enduring, akin to my grandfather’s light drawings in Gjon Mili’s photographs.

ASCR Absolutely. And the sensory experience of the movement of a mobile and the tethering to the work that occurs in this moment is something that is virtually impossible to define. Many photographers, from Marc Vaux to Herbert Matter to Gordon Parks, have attempted to organize a visual representation of this experience, with varying degrees of success. The Matter images in particular give a sense of occupying space defined by the vectors of motion of the sculpture—filling the void. Expanding the picture plane in 1913 with his Guitare et bouteille de Bass, Picasso created a new dynamic for the viewer, a new experience. Calder captured that advance and pushed it further not only with oscillation but also, more importantly, through suspension. This new choreography of motions allowed the viewer to have a unique present-moment experience. It’s an experience that connects the viewer to not just the physical object but to the ephemeral action as visceral sensory moments—never to be repeated.

BRP The maquettes for a monument to Apollinaire is a good example of how this type of masterpiece, in the interior voids left by traces of network forces, strongly permeates our perception;[3] instantly, the powerful image remains fixed in our memory. Modernity brings broader implications via an astral dimension that accelerates our reflection and eventual acceptance. Thus, put into practice, great artists transcribe the mental discourse that fulfills their need to fill the void, or define it; the artists expose their experimentations in subtle areas of research and invite us to partake in the results of their discoveries. Notably, the words of Apollinaire’s The Poet Assassinated resonate with Picasso’s design: L’Oiseau du Bénin declared, “I must model a profound statue out of nothing, like poetry and glory.” “Bravo! Bravo!” cried Tristouse clapping her hands, “A statue out of nothing, empty, that’s lovely.”[4] And when critics attacked my grandfather over the modern nature of his maquette, he responded: “Either I do the job that way or you get someone else.”[5]

ASCR From the outset, critics were also confounded by the radical nature of Calder’s work. His figurative wire sculptures, which he began to develop in the mid-1920s, created void-spaces through transparent and massless volumes, all the while presenting the reality of movement and gesture through intentionally vibrating wire lines. “They are still simple, more simple than before,” Calder wrote of these works in 1929, “and therein lie the great possibilities.”[6] Sometimes he’d use one line of wire, and sometimes he’d use two different gauges of wire to suggest dynamic synergy, moving in and out of the void. The porosity of his wire portraits in particular, underscored by projected shadows on the wall, extend beyond shape and line to engage real-time experience in multiple dimensions. In the 1920s as in the present day, these objects epitomize “the unexpressed but intended and the unintentionally expressed,” to again quote Duchamp.[7]

BRP Fascinating, proving our observation of art is evidenced by our natural visual acuity. I see the works of Calder and Picasso as deeply anchored in art history because they reflect their time. Works of art reinterpret what has already been created by our contemporaries. This is why we endow artists with a shamanic force: they certainly have it, and from it they draw their premonitory acuity. A typographer once told me, “You do not read the blacks on a page: you read the whites,” and it is through this reality that some of our emotions influence our modern behavior.

ASCR Miles Davis often said, “It’s not the notes you play, it’s the notes you don’t play.” My grandfather made a whole body of sculptures in 1943, the so-called Constellations, that capture voids and give a suggestion of the intersection of alternate planar dimensions. These began through a realization that there was a fantastic space on a wall, unnoticed, that could be occupied by perched forms seeming to be ready to spring into action. Like the invisible whites on a page, the wall space he engaged was the area above paintings.

BRP Let me also point out that what poets and artists said and thought in the first half of the twentieth century has partly been forgotten, as if by necessity; fortunately, not all artists have, and thanks to them we are still able to perceive our history differently. To quote an example from Françoise Gilot: “One day while Picasso was painting my breasts in one of those portraits, he said to me, ‘If one occupies oneself with what is full: that is, the object as positive form, the space around it is reduced to almost nothing. If one occupies oneself primarily with the space that surrounds the object, the object is reduced to almost nothing. What interests us most—what is outside or what is inside a form? When you look at Cézanne’s apples, you see that he hasn’t really painted apples, as such. What he did was to paint terribly well the weight of space on their circular form. The form itself is only a hollow area with sufficient pressure applied to it by the space surrounding it to make the apple seem to appear, even though in reality it doesn’t exist. It’s the rhythmic thrust of space on the form that counts.’”[8]

ASCR One of the great questions is this fascination with the idea of drawing in three dimensions, or how Calder and Picasso achieved a “rhythmic thrust” within space. In 1929, a few critics described Calder’s sculptures as being “drawings in space,” and three years later, González wrote in his notebook about Picasso drawing in space. Calder’s and Picasso’s preoccupations with the nonpresent, the lacking, the void, became not only the subject of the actual matter but also the anti-matter in the creation of works of art. For Calder, it was not just the metal and the paint but the space that they cut through; that is the existence of the work of art, in the act of performance and engagement. As for Picasso, in terms of the maquette for a monument to Apollinaire, it began with a series of line and dot drawings—or points in light, with connecting lines of tension defining a void—that originated in celestial maps. But of course, let’s not forget the common molecular model of spheres held in proximity by wires; but in the assemblage of atoms we call molecules, there are no interconnected wires, only invisible vibrational resonances that create the bond.

BRP My grandfather’s line drawings, like much of his work, are at once intimate and very much alive. Speaking with Anatole Jakovsky in 1946, he remarked, “Look at these drawings: it is absolutely not because I wanted to stylize them that they became what they are. The superficial quite simply disappeared by its own means. I did not seek anything ‘deliberately.’ For this, there is obviously no other key than the one of poetry. If lines and forms rhyme and liven up, it is like a poem. For this purpose, no need for a lot of words. Sometimes there is more poetry in two or three lines than in a long poem.”[9] One of the most remarkable things about him is that he could do a line drawing in the morning and then, later in the day, make a neoclassical rendering of the same subject. Here again we have porosity, between the figure and abstraction, past and present, shape and space—and nonspace.

ASCR Calder confronted the void in his figurative wire sculptures, or drawings in space. And when he turned completely to abstraction in 1930, he fully embraced the void. His first exhibition of abstract wire sculptures in 1931 at Galerie Percier demonstrated his complete intellectual fascination with the absence of matter and the resonating energy that vibrates out of the inherent masslessness. Interestingly, this was the moment when the two artists first met: Picasso came to Percier in the afternoon before the vernissage to meet Calder and have time to explore his radical new works.

BRP Many artists have told me that when they look at another artist’s work, they know what elements to introduce into their own work in a very honest way. I’m sure that Picasso knew what Calder was doing—and vice versa—and that was enough for him. To quote Gilot, “Picasso had always wanted to make a sculpture that didn’t touch the ground.”[10]

ASCR What is the difference between the void and the abyss? The void is nothingness—alternate dimensions beyond the third—the commonality of all things or emotional transparency. The abyss is lost-longing, desperation, or emotional opacity. Nietzsche wrote, “Man is a rope stretched between the animal and the Superman—a rope over an abyss. A dangerous crossing, a dangerous wayfaring, a dangerous looking-back, a dangerous trembling and halting. What is great in man is that he is a bridge and not a goal: what is lovable in man is that he is an over-going and a down-going.”[11]

BRP Within the abyss, you don’t return!

ASCR While both the void and the abyss are dynamically represented in Picasso, only the void is represented in Calder—and it is within the flexible framework of the void that both artists meet. Picasso’s Le Taureau, a series of eleven lithographs created in December 1945 and January 1946, are not really about a reduction of mass but seem to be about the expansion of gesture. The progression from the solidity of the volumetric figure to simplified lines of passionate gesture is about refining the image, scraping away, accessing the truth of the subject. Likewise, the mobile projects into places that it doesn’t occupy. There is a triangulation that occurs between the viewer and the mobile in its innumerable variations—these ephemeral dynamic realities result in a very personal experience in the present moment. The mobile is alive with gestures, with every performance unique. These gestures served as a prelude to mid-century Abstract Expressionism, and the open activity of the mobile compositions had an effect on the music of John Cage and others.[12] In Scarlet Digitals, for example, Calder created three movements that present the shifting presence of absence, a song of silence. “A full void, an enriching emptiness, a resonating or eloquent silence,” to quote Susan Sontag.[13]

BRP Picasso’s exploration of the void was a creative urgency that arose from his awareness of life’s end. That also relates to the question of space and time, and a kind of panic or anxiety about the passing of time in his work. He once confessed to Christian Zervos, “Each time I begin a painting, I have the feeling of leaping into the void. I never know whether I’ll land on my feet.”[14] He had to work to survive, to push away death.

ASCR For my grandfather, it was about unseen forces. Things we feel, like gravity or wind, are active forces that we think we know, but we don’t yet know how to scientifically define something like intuition or precognition. Calder explored that parallel as something no less real, driven by sensations of awareness that science has not yet caught up to; for instance, he wanted to know how atoms are held in resonance in a molecule. Some of us have expanded our perceptions—a third eye—and Calder explored that reality, too. Author James Jones once likened the sculptured voids in Calder’s stabiles, seen here in works like Morning Cobweb (intermediate maquette, 1967), to portals: “I had the nervous feeling that if I walked in under one of the larger ones, I might not be there; that if I pushed my hand between elements or through a hole of the smaller ones, the hand would disappear.”[15]

BRP We look at things always from our ego. Day to day, our perception of an object or event changes, and Calder dances with that. There’s always a kind of magic in his work, especially the panels: each time I look at them I see something new. It’s like looking at a tree in the countryside, with the changing of the leaves, the sunset. At that moment, you stop thinking about the self.

ASCR Hopefully. Nature is a different thing, though. The elements in the mobiles are not leaves; these are not abstractions of nature. Mobiles extend beyond nature, addressing the immense grandeur of everythingness. Calder made an edition for the Jakovsky portfolio in 1935, as did Picasso. But unlike all the other prints, Calder’s image is not a handsome work of art. It is a proposal—a diagram for a quantum performance. “For though the lightness of a pierced or serrated solid or surface is extremely interesting the still greater lack of weight of deployed nuclei is much more so,” wrote my grandfather. “I say nuclei, for to me whatever sphere, or other form, I use in these constructions does not necessarily mean a body of that size, shape or color, but may mean a more minute system of bodies, an atmospheric condition, or even a void. I.E. the idea that one can compose any things of which he can conceive.”[16] Calder’s works propose to generate the transformation from one type of energy into another.

BRP With Bull’s Head, one can instantly identify the modern desire to appropriate everyday objects and “transform” them into ready-mades.[17] Picasso created Bull’s Head as a tribute to González, and it belongs to the type of conceptual creation that forces the beholder to introspect the emotions triggered by the creative act;

the opposition in antagonistic forces is what allows us to transform the way in which we see things. In Picasso’s words, “One day I took the seat and handlebars, put them together, and made a bull’s head. Very good. But what I should have done immediately afterward was to throw the bull’s head away. Onto the street, into the gutter, throw it somewhere, but throw it away. Then a worker would have come by, picked it up, and found that he could perhaps make a bicycle seat and handlebars out of this bull’s head. And he does it … That would have been wonderful. It is the gift of transformation.”[18] Picasso brought this transformative spirit into his paintings, as well: “I want an equilibrium you can grab for and catch hold of, not one that sits there, ready-made, waiting for you,” he once told Gilot.[19]

ASCR That reminds me of the time my grandfather deposited a stone horse that he had carved into a hole in the sidewalk outside of his Paris studio. The hole would always fill with water, so my grandfather thought he should fill it in. Then Mary Reynolds and Duchamp discovered the stone horse and dug it up! “They thought they had discovered a Roman ruin,” my grandfather recalled.[20]

BRP The dialogue between Calder and Picasso must remain free, in the same manner that these two artists acknowledged a sense of completion in the unfinished—much in the spirit of what Duchamp would call une approximation démontable. Picasso could very well have been directly referencing Calder when he wrote in 1937: “A picture is not thought out and settled beforehand; while it is being done it changes as one’s thoughts change. And when it is finished it still goes on changing, according to the state of mind of whoever is looking at it. A picture lives a life like a living creature, undergoing the changes imposed on us by our life from day to day. That is natural enough, as the picture only lives through the man who is looking at it.”[21]

ASCR Zervos, too, could have been writing about Calder when he said of Picasso, “His work thus lacks the mechanical quality that comes from the exercise of will, premeditation, and slow and circumspect execution.”[22] Calder didn’t calculate. Often critics have directed our attention to his sculptures as being planned or calculated or engineered, but his process was an open one. He seemed to be in a trance when at work; certainly it was not his brain at work, but his hands seemed without intentional command. His forms devised of intersecting planes were nonetheless solid to Calder—he felt the solidity. These could, from certain angles, also be completely transparent. A transparent solidity. In his words, “When I use two circles of wire intersecting at right angles, this to me is a sphere—and when I use two or more sheets of metal cut into shapes and mounted at angles to each other, I feel that there is a solid form, perhaps concave, perhaps convex, filling in the dihedral angles between them. I do not have a definite idea of what this would be like, I merely sense it and occupy myself with the shapes one actually sees.”[23] In terms of his process, he would make a series of resonating shapes that had a relative harmonic. Then, he would lay them out flat on a table and organize them like collage elements, moving pieces farther apart and then closer to charge the dynamic resonances. He actively felt the resonant frequency. He would intuitively add element after element and then stitch them together with wire to create the central balance.

BRP Calder and Picasso were both outsiders who challenged the practice for all artists. They were both a kind of anarchist. They urged forms and shapes out of the void to show the beauty of the outsider, without regard to what’s sellable, what’s the popular mode. They didn’t pander at all.

ASCR They were both self-assassins who reinvented through the destruction of prior successes!

BRP Yes. They reinvented their processes every day. Eventually, both of them came to reject the systems of the past, even though this created confusion among those who had accepted their prior revolutionary acts.

A deep exploration of the genius of Picasso and Calder reveals synergies between their work so profound as to have shaped and reshaped modernity from their day to ours. What we see when we look at the achievements of these two transcendent artists are intuitions and apprehensions so powerful as to have transformed the very nature of art. Beginning anew each morning, Picasso and Calder went into their studios and pursued a path so personal as to seem shamanistic. For Picasso, it was almost an automatic drive to stave off death, the knowledge that each day was one day less. For Calder, each day was an opportunity to pull eternal energy through an oculus to coalesce in the present, crystallizing dimensional inspirations in our consciousness. Picasso and Calder both had that absolute drive. Picasso’s drive came from his chest; Calder’s came from the sky.

Musée Picasso, Paris. Calder-Picasso. 19 February–25 August 2019.

Group ExhibitionAddison Gallery of American Art, Andover, Massachusetts. 17 Mobiles by Alexander Calder. Exhibition catalogue. 1943.

Alexander Calder, Statement

Solo Exhibition CatalogueAlmine Rech Gallery, New York. Calder and Picasso. Exhibition catalogue. 2016.

Robert Slifkin, The Mobile Line

Susan Braeuer Dam, Liberating Lines

Jordana Mendelson, Picasso, Miró, and Calder at the 1937 Spanish Pavilion in Paris

Group Exhibition CataloguePace Gallery, New York, and Acquavella Galleries Inc., New York. Calder/Miró: Constellations. Exhibition catalogue. New York: Rizzoli, 2017. Boxed set includes three volumes: Calder: Constellations, Miró: Constellations, and Calder/Miró: Chronology and Correspondence.

Alexander S. C. Rower, Deployed Nuclei

Group Exhibition CatalogueDenver Botanic Gardens. Calder: Monumental. Exhibition catalogue. 2017.

Alexander S. C. Rower, Approximations of Perfection

Solo Exhibition Catalogue