Alexander Calder once recalled an incident that occurred between him and his wife Louisa shortly after they married. The two were living in Paris and had decided to hire a live-in cook. Louisa set out to furnish a spare bedroom for the new employee, with items including a broc and washbasin. Describing the distaste he felt towards her purchase, Calder mused, “A broc is a beautiful thing of conical shape, tall and slender—and instead she had bought a pitcher, fat and dumpy, while the basin had a flat bottom … I feel that if one accepts things which one does not approve of, it is the beginning of the end … Bad taste always boomerangs.”[1] Scandalised by the offending items, Calder destroyed them, driving a spike through each, despite Louisa’s protest that he wouldn’t “see these things anyway, because they’ll be in the cook’s room.”[2]

In the decade since I first recounted it in my essay A Broc is a Beautiful Thing: Calder’s Domestic Treasures[3] (2007), I’ve mulled this story over countless times, thinking about how Louisa once wrote to her mother before she and Calder married of the artist’s “tremendous originality, imagination and humour,” which she declared, “appeal to me very much and which make life colorful and worthwhile.”[4] How alarming it must have been for the newlywed to see her jocular husband fly into a rage over a seemingly inconsequential pair of objects. What caused such a vehement reaction in Calder?

This rare display of ferocity may seem surprising coming from an artist known for his good nature (although Calder’s surviving family confirms that privately he was often far less amiable), however, the recollection is illuminating. Calder’s aesthetic rigor and commitment to solid design underlie his demeanor. The artist demanded perfection from the tools and objects that surrounded him, and so, rather than give in to using deficient mass-manufactured goods, his frequent solution was to make superior versions with his own hands. For every mobile, every monumental public sculpture, every wire portrait for which he is renowned, there is also a humble ashtray, a pragmatic folding table, or an electric toaster that is also Calder-devised. Most of these inventions were constructed for personal use. Louisa Calder and the couple’s two daughters, Sandra and Mary, also benefited from Calder’s ingenuity: a baby rattle, a set of repurposed teacups, and a bacon fork much beloved by Louisa all attest to this. Calder’s domestic items were often beautiful, but all were primarily conceived to be functional and sturdy. His striking ingenuity in the creation of these objects had its roots in his marvelous output of early toys, which treated humor as an intellectual pursuit, and also, of course, his famous Cirque Calder, an assemblage of objects made from found and recycled articles and other proletarian materials. Filtered through the lens of these early achievements, Calder’s household objects take on a fresh significance.

The essence of Calder’s politics can be found in these humble pursuits. Calder could be demonstrably political when moved by dire or extreme situations. His contribution of Mercury Fountain to the Spanish Pavilion at the 1937 World’s Fair in Paris, which was displayed alongside Picasso’s Guernica in support of the Spanish Republic (which was at the time under siege by Franco’s Fascists), is an early testament to this, as is his participation in anti-Vietnam protests during the 1960s. So too is his signature on the New Year’s advertisement he and Louisa took out in the New York Times in 1966, on behalf of the organization SANE (The Committee for a SANE Nuclear Policy), where they contended:

A New Year, New World. Hope for: An end to hypocrisy, self-righteousness, self-interest, expediency, distortion and fear, wherever they exist. With great respect for those who rightly question brutality, and speak out strongly for a more civilized world. Our only hope is in thoughtful Men—Reason is not treason.[5]

Despite these public declarations of his political position, Calder’s work rarely displayed an overtly political perspective, unlike the work of his contemporaries such as André Breton or Hans Bellmer, for instance. However, Calder’s handmade, recycled, or modified utilitarian objects—which were part and parcel of the Calder family’s everyday life—manifest his staunch commitment to a personal politics that is, when examined, impossible to separate from a broader worldview. The domestic items are unequivocal solutions to everyday problems the artist might have encountered as he went about his daily life. Also embedded into the creation of these items is the personal significance Calder placed on ritual endeavors above commercial aims. Writing of Calder’s mobiles, Alex J. Taylor remarked that, “Like automated appliances … Calder’s ‘invention’ served as another kind of manifestation of ‘Yankee ingenuity’ … and provided the cultural correlate of high-tech novelties promised by American abundance.”[6] However, I maintain the opposite: Calder’s household objects eschew the rampant capitalism that came to define American political and cultural life in the twentieth century, and in fact highlight the pragmatic philosophy Calder espoused, less in words, but rather, in the very way he lived and worked.

The pitcher and basin are not the only instances where mass-market design raised Calder’s ire to the point of destruction. The remnants of a manufacturing stamp in the metal uncovered during recent conservation of the baby rattle (c. 1935) Calder made for his infant daughter show that it was made from a piece of Tiffany silver. Likely given to Calder and Louisa as a wedding gift, the artist saw no need for a piece of futile, decorative silver, even one with the label of an extravagant jeweler. So he broke it down and refashioned it into a plaything for his baby, alchemically suffusing the Tiffany silver with a purpose. Into his middle age and beyond, when the artist had achieved enough success that he had the means to live quite comfortably (even grandly if he had chosen), Calder maintained his rustic lifestyle, complete with useful utensils and tools he fashioned or modified himself. For Calder, his self-made items functioned in a superior way to the more readily available, store-bought alternatives.

Calder’s predilection for original thought manifested itself from childhood, and his mechanical inclination was evident from a young age. As a small boy, his parents left him and his older sister Peggy with family friends in Philadelphia for an extended period while they traveled across the country by train to the American Southwest, seeking treatment for his father’s ailing health. Calder remembered later, “I took my parents’ departure and our new surroundings as a natural course of events. Mother wrote to us about being able to see the locomotive when the train ran around a curve. There was a mechanical element in this picture which interested me, I suppose.”[7] What is most remarkable is that even in the face of this potentially traumatizing event, Calder’s intellectual curiosity prevailed. Indeed, he often made good use of his inventive nature to create toys and games for himself and Peggy. When he was eight years old, Calder and his family moved to Pasadena, California. Given the basement of their house to use as his workshop, Calder discovered his facility with tools and materials. He later remembered that his parents were supportive of his early endeavors, noting that, “Mother and father were all for my efforts to build things myself—they approved of the homemade.”[8] Besides crafting jewelry for his sister’s dolls from bits of wire he found in the streets, he constructed other ingenious toys and contraptions. A neighbor who fought a losing battle with slugs in the garden received a homemade slug-killer, for example. “I made him a two-pronged fork out of wire with a trigger ejector with which he could demolish the slugs at his ease.”[9] Even more sophisticated was a small puzzle game given by Calder to his father as a birthday gift around 1911:

A small wooden rectangle was divided into six pens by fourpenny nails. A tiger, a lion, and three bears, all suitably painted, were fastened into slots so that they could be moved from pen to pen. The challenge was to clean the pens without having two animals in the same pen at once (thus avoiding bloodshed).[10]

Calder constructed all of the game’s parts—hammering the nails into the block and carving the little sliding animals. Made entirely from items he was able to find around the house or on the street, the advanced level of planning and strategy behind the innovative game is impressive by any standards. At the time of its creation, Calder was not yet twelve years old.

Graduating from Stevens Institute of Technology in Hoboken, New Jersey, in 1919, Calder nurtured these early interests, undertaking a degree in mechanical engineering. For several years afterward, he assumed a nomadic existence, bouncing from job to job. He had no problem finding engineering work, but little of it proved stimulating to him. Then, in 1922, while working at a logging camp in Washington State as a timekeeper, Calder spontaneously asked his mother, who was living in New York, to send him a set of oil paints. She obliged, and he began to paint the surrounding landscapes. Something resonated and shortly thereafter, he quit his engineering job and returned to New York to become an artist.

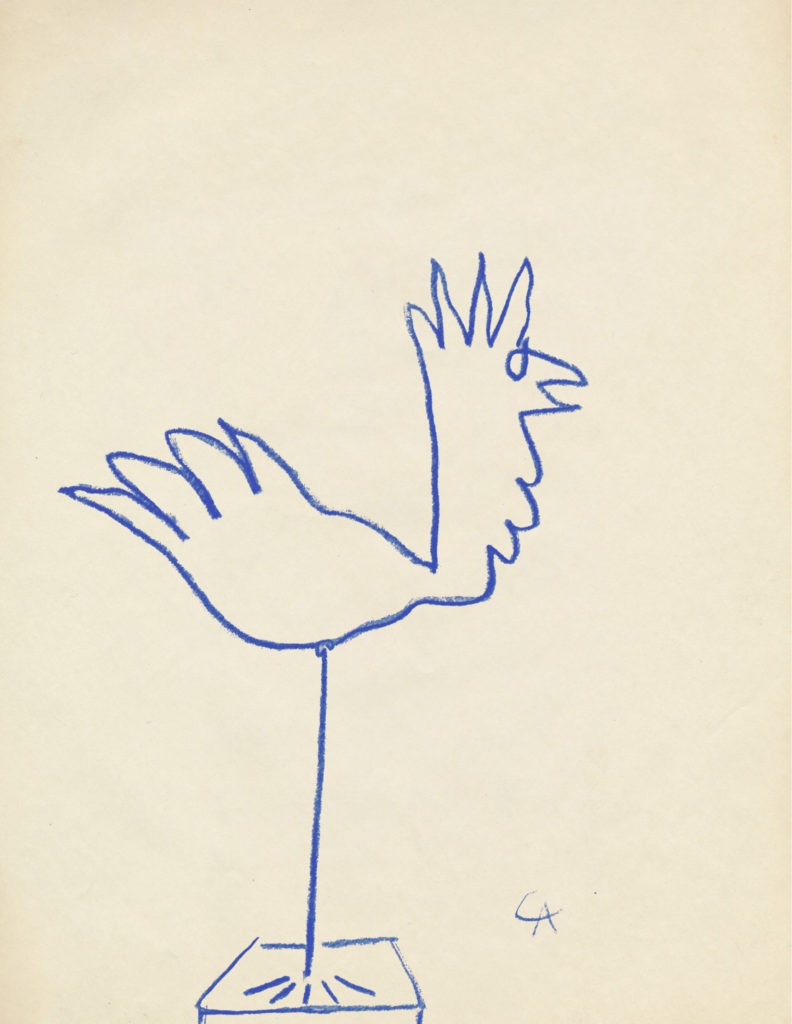

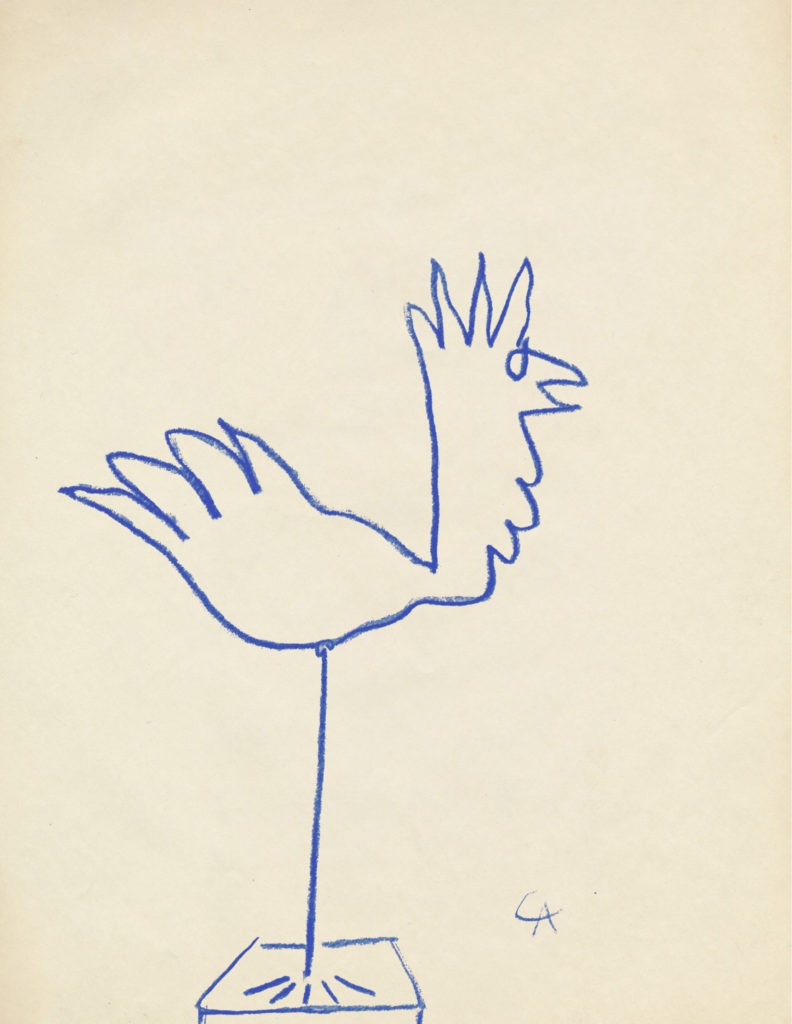

When Calder arrived, he enrolled in drawing and painting classes at the Art Students League, at first thinking that he might become a painter. Living in a cheap cold-water flat on a student’s budget, he took to hand-making whatever necessities he lacked. Calder had no watch or clock in the tiny but sunny apartment he rented on Fourteenth Street, so he made himself a working sundial out of wire. In the form of a rooster, this astonishing object and pragmatic device (sadly no longer extant) is Calder’s earliest known wire sculpture.

Calder soon found a job as a freelance illustrator for the National Police Gazette, and for the next several years sketched dozens of line drawings for the magazine. In 1925, the Gazette sent Calder to cover the Ringling Bros. and Barnum & Bailey Circus. In the early twentieth century, the circus still enjoyed huge popularity as adult entertainment. At the time, it was not merely an amusement for children, but an intellectual diversion that spurred public dialogue and commentary. “I spent two full weeks there practically every day and night,”[11] Calder noted, over which time he became intimately familiarised with the spectacle. He studied every detail meticulously, paying particular attention to “how the rigging was actuated” and “the spatial relationships within the tent.”[12] This experience served him when he departed for Paris the following year—having been recommended to the city by “everyone who had been there”[13]—for it was there that the Cirque Calder was born. In the mid-1920s, Paris was the undisputed capital of the art world, and Calder—still thinking of himself primarily as a painter—believed his work would advance there. He arrived in the summer and began work on his celebrated Cirque. He was familiar with the types of movement performed by the various troupers and animals and began to create diminutive, moving figures whose actions were based on what he had seen at Ringling Brothers. The miniature players were fabricated from cloth, wood, found objects, and most importantly, wire, a material both structurally sturdy and pliable.

Cirque Calder is a feat of imagination. Composed of hundreds of pieces, it includes every circus performer in small scale: trapeze artists with articulated limbs, a ring-master who brings a megaphone up to his mouth to shout to the crowd, a dog that flips, a horse that gallops—these characters all existed in Cirque Calder just as they did in the live circus. Calder soon became the toast of the Parisian avant-garde, presenting elaborate, two-hour performances in which each of the figures played a role. Soon, his friends were bringing their friends to see this groundbreaking piece of performance art. Enthusiasts marveled at the production’s mechanical intricacy and also at the way these mechanics still yielded to chance, just like life. Cirque Calder was not a mere replica of a circus—it was an actual circus, existing on its own terms. Legrand-Chabrier, the influential Parisian cultural critic, observed:

Here is a model assembly of a circus tent, a surprising and complicated flying trapeze apparatus with three trapezes that permits, by the play of a wire manoeuvred by a finger, and not obligatorily, to make two trapezists of cork bodies joined to wire arms and legs execute the same tricks as our flying trapezists of flesh and blood. All this combined and balanced according to the laws of physics in action such that it allows the miracles of circus acrobatics.[14]

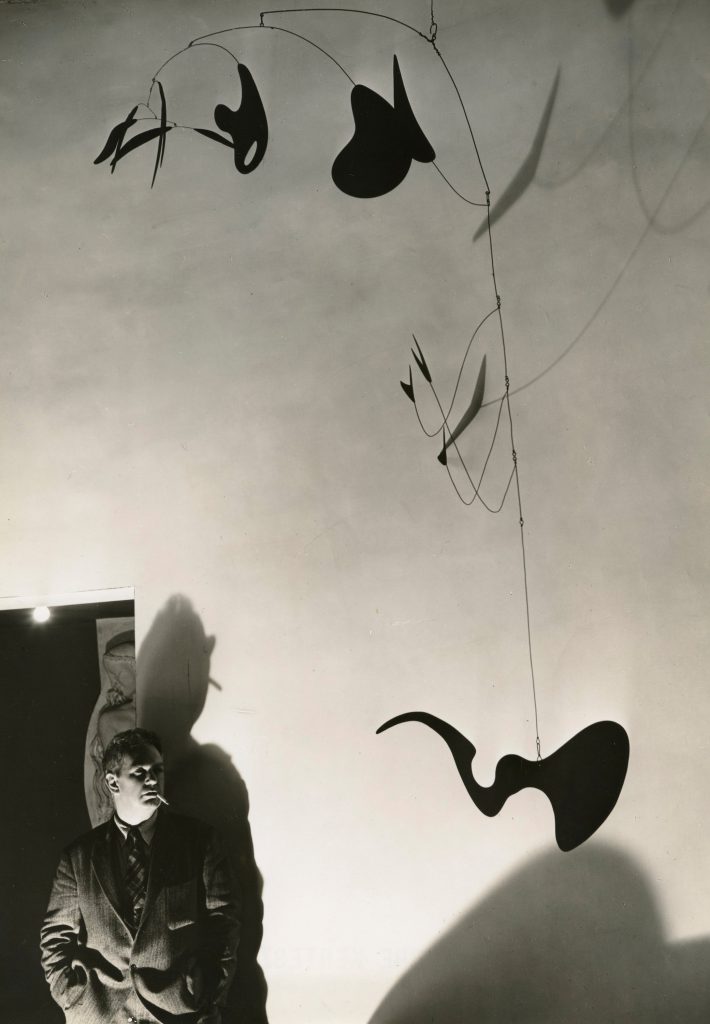

Installation photograph, Calder: From the Stony River to the Sky, Hauser & Wirth, Somerset, England, 2018

Photograph by Ken AdlardInstallation photograph, Calder: From the Stony River to the Sky, Hauser & Wirth, Somerset, England, 2018

Photograph by Ken Adlard

Calder met Louisa aboard a ship, on one of the several transcontinental voyages of his early career. They married in early 1931 in Concord, Massachusetts, and spent most of the next two years living in Paris. Upon their return to the United States in 1933 and, after borrowing a little money from a friend and drawing on a life insurance policy, the Calders put a down payment on their first home, a dilapidated farmhouse in Roxbury, Connecticut. “Limitation was the source of invention,”[15] Calder’s son-in-law Jean Davidson once wrote of the artist, which may partially explain the impetus for the countless early housewares and furniture Calder developed for their use. As is often the case after the purchase of a first house, finances were tight and “the place needed everything—plumbing, heating, electricity, the works,” Calder’s biographer, Jed Perl has noted.[16] With these specialized undertakings requiring professional oversight (and therefore a certain amount of money), Calder, with his can-do spirit, often simply made himself the things he and Louisa needed in the early years of home-ownership. The beauty of these objects was never compromised by functionality, and their functionality was never inhibited at the expense of form.

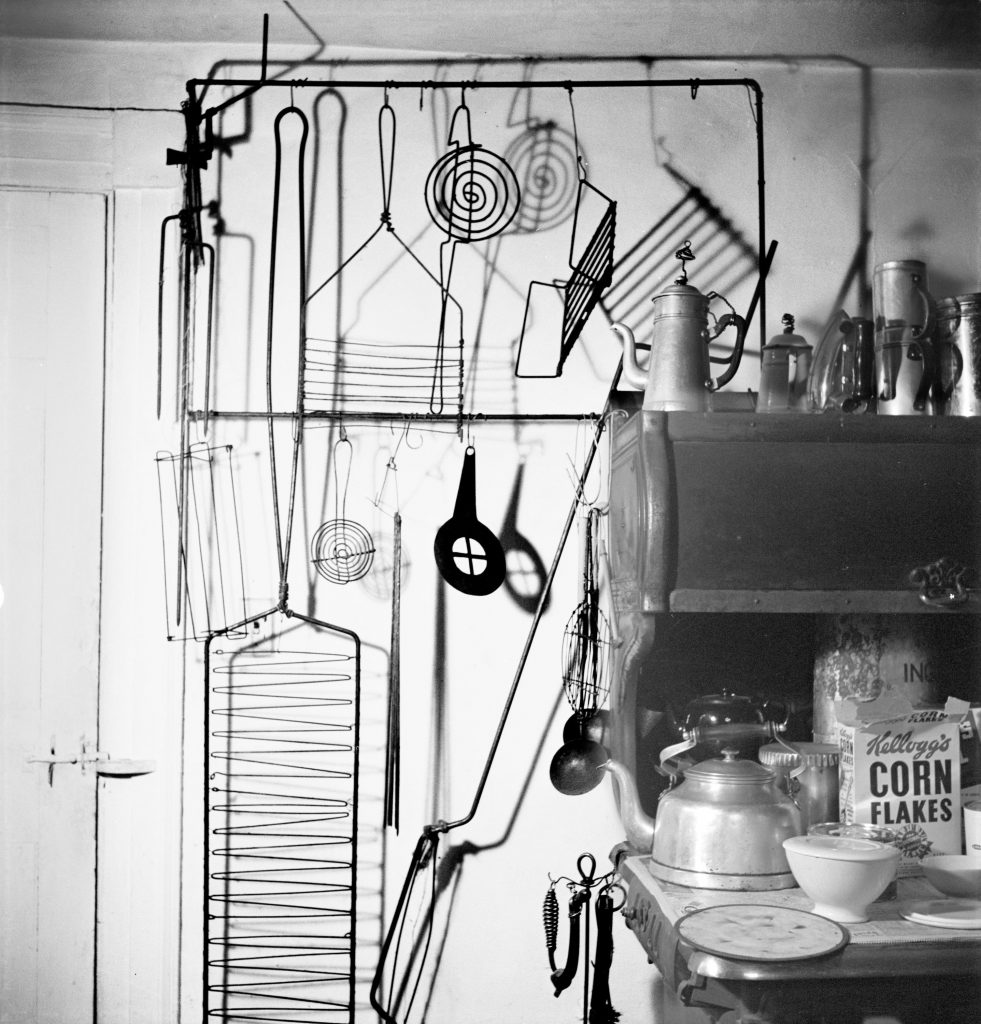

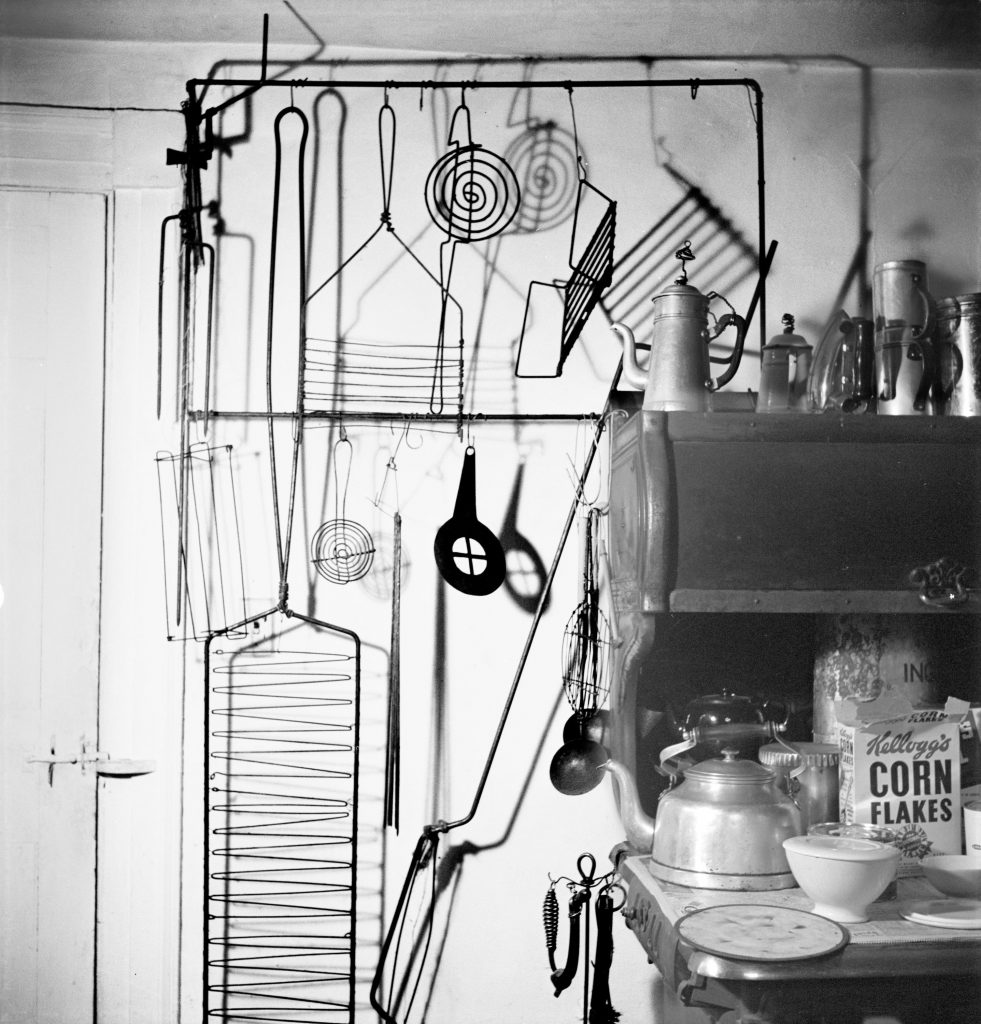

Photographs of the Calder kitchen in the Roxbury house attest to the artist’s prodigious output. One image of the kitchen shows “a room that looks … almost more like a fantasy of a country kitchen than an actual place to prepare and consume meals.”[17] A large wall rack displayed a wide range of hand-made cooking devices, including grills to hold and cook food, an example of which is included in the exhibition, fashioned in a variety of sizes. Another rack was devoted to utensils: serving spoons and forks, not unlike the oversize aluminum measuring spoons and fanciful Figa fork (c. 1948) shown here. Even the cabinets in the Roxbury kitchen are Calder-made, some of the earliest and most substantial of his kitchen creations.

Our furniture and effects had come from Paris in six or seven large cases made out of some North European white wood. Out of one of these, I made a corner cupboard for the new kitchen, in which to hang pots and pans. Later on, after the fire, I made another cupboard … and for that one I used a large case which came with some of my jewelry back from the Museum of Modern Art … I also housed in the legs of the sink and put a hook of my own manufacture on the door, in the middle.[18]

Calder was also inclined towards making improvements on his creations. This was a common process for the artist: to make an object, study its design, and then revise it, with amendments made in the next attempt. It was in this ritualistic way that Calder eventually invented his first mobile—its movements driven entirely by the breeze—after initially experimenting with the creation of motor-driven kinetic sculpture. The earliest known free-hanging mobile, Small Sphere and Heavy Sphere (1932/33) is largely comprised of repurposed objects. The mobile consists of two spheres, each suspended on its own line from a horizontal rod hanging from the ceiling, and encircled by a variety of found objects, such as a discarded tin can, empty glass bottles, and a small, wooden crate. When the larger sphere, made of iron, is swung, it causes the smaller, lighter-weight sphere to oscillate freely, creating an unpredictable cacophony of noises. Eventually, mobiles—usually made from sheet metal and wire—would become Calder’s most celebrated invention.

Small Sphere and Heavy Sphere, in its utilization of reused items, relates not only to later mobiles like Tines (1943)—whose elements are composed of found detritus—but also to Calder’s more unassuming domestic objects. For instance, Calder devised a superb dinner bell from a Mexican wine goblet that had lost its stem and assorted pieces of glass. With the colorful shards swinging from wire looped around the waist of the glass, the bell might at first seem too fragile to summon anyone to a supper table; but it is surprisingly assured and luminous in tone, its dangling elements evoking Calder’s mobile sculptures. Likewise, even in their lean years, the kitchen toaster—an inexpensive, commercially abundant object—was an item the Calders probably could have afforded for their home. But Calder believed his visualization of a toaster was stronger than that of a mass-produced one, which led him to develop toasters of his own conception. One design includes an ingenious “warming plate” upon which toasted slices of bread could rest, melting the butter via the heat generated by the machine below. He eventually made five different toasters, each having a similar basic framework but minor variations in design and function. This system of working was not dissimilar from that of his late career, when he employed this process of re-working, even during the creation of his massive public sculptures. As Alexander S. C. Rower noted:

Sometimes a 1:10 scale model would be made and then a 1:5 model would be constructed. Wind tunnel testing was employed to confirm the stability of the form … Calder himself approved the plans for any changes, and he continually refined his sculptures using aesthetic solutions to the structural problems … At each step, Calder designed and redesigned his original composition, altering shapes, materials, and balances as it suited him.[19]

Whether a monumental stabile soaring above a public plaza or a domestic item intended for personal use, the artist’s procedural rigor remained constant.

Deeply embedded in these processes is Calder’s solemn accedence to ritual, not in the strictly religious sense but rather in the way certain habitual activities, performed with reverence, become divine. As ritual studies scholar, Catherine Bell has written, “Activities that are merely routinized are not the best examples of the ritual-like nature of invariance unless they are also concerned with precision and control.”[20] In Alexander Calder: From the Stony River to the Sky, the installation of Calder’s household objects in specialized groupings and domestic tableaux allude to the significance of drinking coffee, smoking a cigarette, and playing chess as acts of ritual rather than as simple, routine undertakings. Each of these activities is one in which Calder not only partook but made an intrinsic part of his life. By performing them ceremoniously, Calder imbued a personal life force into the handmade objects he used to accomplish these rituals, elevating them from plebeian household items into hallowed totems.

“The morning coffee. I’m not sure why I drink it. Maybe it’s the ritual / of the cup, the spoon, the hot water, the milk, and the little heap of / brown grit, the way they come together to form a nail I can hang the day on,” wrote poet Ron Padgett.[21] And so it was with Calder. Early in Calder and Louisa’s marriage, when the couple were still living in Paris, Calder devised a contraption that allowed him to have his morning coffee in bed. As artist and friend of the Calders Stanley William Hayter describes:

The kitchen was on the soupente level up a short stairway from the studio in which was his bed. An elaborate machine with two wires issued from the kitchen on which a species of cradle carried the coffee pot. By dint of hauling on one string the gas could be lit under the percolator; another string turned it off and then the coffee could be carried on the wires down to the side of the bed without Sandy having to get up. I think it was his wife Louisa … who told me that should the apparatus fail to function Sandy would get up, repair it, return to bed and continue the whole routine.[22]

Even this early in his domestic life, the observance of morning coffee was so primary that Calder preferred to spend his leisurely morning hours before beginning the bustle of the day improving the device that allowed him his ritual as he envisioned it, rather than simply pouring the coffee and returning to bed. Later on, the Calder’s house in Roxbury, not being a loft, made replicating this device impossible, but the same obsessive care still went into making and improving the coffee items that were in service to the family during their decades living in the home. The coffee-making apparatus itself was actually a store-bought item, a Moka pot based on the classic Italian design. The Calders’ pot seems to have been badly fashioned so that the coffee grinds tended to slip out of the pot when the coffee was being poured. Likewise, the knob that held the lid closed grew hot along with the rest of the metal pot, which made holding the lid closed near impossible. Rather than buying a better pot, Calder improved upon the design of the existing one. Two elegant twists of wire became the solution to coffee-pouring troubles: one affixed to the handle pushed down on the lid when pressed, keeping the grind bucket held fast within the container, while the other looped upwards from the hot knob to prevent singed fingertips. As any serious coffee aficionado knows, the receptacle into which the drink is poured matters—and so, Calder reimagined an inexpensive set of mass-produced teacups. The original cups had no handles and were therefore difficult to hold when hot. Calder appended zarfs, that, with their graceful spirals of brass wire (akin to those found in Calder’s jewelry), elevated the stubby little cups into sacred drinking vessels. The serving trays, coffee spoons, creamer, and sugar scoop round out the tableaux, all pieces modified from their original, mass-produced sources (or else up-cycled from materials Calder had ready at hand). Of particular note is the copper serving tray, derived from a series of etchings on copper plates Calder made when he illustrated the 1948 book, Selected Fables, by Jean de La Fontaine. The etching on this particular plate did not make the cut for the final version of the book, so Calder bent it into a tray, sparing the handsome copper from the trash.

The selection of ashtrays on display here suggests the importance of smoking for Calder as a sacrosanct ritual. Just a few generations ago smoking was an accepted social rite, and Calder himself was frequently photographed with a cigarette dangling from his lips. Implicit in the design of these ashtrays is Calder’s desire to live with quality-made, original objects. Though crafted of simple materials—mainly emptied coffee or olive oil cans that likely would have been otherwise discarded—every ashtray is unique. One example, the animal ashtray (c. 1943), is a Beech Nut brand coffee can repurposed into a fantastical beast with a head, tail, and eight legs, every appendage providing a discrete tray upon which to rest a cigarette, so that one ashtray could easily accommodate a party of ten. Again, rather than simply buying a number of cheap ashtrays to place around the house, Calder chose to create his own. Taking this inclination one step further, he not only made each one a singular object, he often improved their functionality. The American art critic John Canaday, once a visitor to Calder’s home, put it thus:

He has … solved the ashtray problem, a major annoyance in contemporary life, with a did-it-himself contraption that (a) holds the cigarette securely when it is laid down—no rolling, no dropping, no falling; (b) accommodates vast quantities of ashes in such a way that they can’t blow out over the table and won’t spill even if the thing falls on the floor; (c) is decorative; (d) has sentimental associative values; (e) costs only a few cents, or nothing; and (f) is therefore, disposable—although no one who has ever managed to get away with one has been known to treat it with anything but reverence.[23]

Canaday’s ecclesiastical language speaks to both the mid-century importance placed on cigarette smoking as a ritual activity and also the totemic qualities with which Calder’s ashtrays were imbued. Calder’s chess set (c. 1944), the centerpiece of another domestic scene installed in the present exhibition, is robust with reworked materials, its pieces constructed from a sawed-off baluster and the feet of an old sofa. One of only three sets Calder was known to have made, this one was likely created for and exhibited in the landmark 1944 exhibition, The Imagery of Chess, organized by Marcel Duchamp and held at the Julien Levy Gallery in New York. The roster of artists who participated in the exhibition reads like a Who’s Who of modern artists (Isamu Noguchi, Marcel Duchamp, Max Ernst and Arshile Gorky to name only a few), but Calder’s chess set was the most “American in spirit—large, bright and bold, but rough-hewn from whatever resources were at hand.”[24] With its long historical association with battle, the game of chess enjoyed renewed popularity in the 1940s, as the world plunged deeper into the Second World War. The game resonated powerfully with many prominent artists of the day, including Calder, who was known to occasionally enjoy a round. One can easily imagine him tucked into a nook in Roxbury with a companion, seated on wooden, Calder-made chairs, hovering over a low-slung, Calder-made aluminum table, strategizing his next move by the light of a Calder-made spot lamp. Although Calder may not have been the most devoted chess player, his friendships with artists who were—like those mentioned above, as well as others like Yves Tanguy and Kay Sage, who were his neighbors in Connecticut—attuned him to the gravity and ceremony the game could impart amongst its disciples.

Louisa Calder once declared that a two-pronged object—one in the arsenal of kitchen items produced by her husband—was in fact, “the best bacon fork in the world.”[25] Despite their early row over the inferior pitcher and washbasin, the two were united in their distaste for shoddy goods, and Calder’s spurning of the mass-produced in favor of the handmade whenever possible. Toaster, ashtray, coffee cup: Calder produced a lifetime’s worth of practical items that are mundane in name only. What Louisa and the couple’s children received in return was a lifetime living in a house of magic, where a bacon fork was never simply a bacon fork. Their respect for everyday ritual grew from a mutual and deeply ingrained belief that the mass-market object, though easily acquired, was not a better solution than a common item alchemically transformed by an artist’s hands. A piece of fine silver becomes a baby’s plaything; a shattered wine glass becomes a dinner bell; a sheet of metal becomes a printing device and then a coffee tray. Bad taste always boomerangs, Calder said. There are politics in that.

Hauser & Wirth, Somerset, England. Calder: From the Stony River to the Sky. 26 May 2018–9 September 2018.

Solo ExhibitionHauser & Wirth, Somerset, England. Calder: From the Stony River to the Sky. Exhibition catalogue. 2018.

Susan Braeuer Dam, For the Open Air

Jessica Holmes, More than Beautiful: Politics and Ritual in Calder’s Domestic Items

Solo Exhibition Catalogue“Calder in France.” Cahiers d’Art, no. 1 (2015). Edited by Alexander S. C. Rower.

Susan Braeuer Dam, Calder in France

Robert Melvin Rubin, An Architecture of Making: Saché and Roxbury

Agnès Varda in conversation with Joan Simon

Magazine, MonographMusée Picasso, Paris. Calder-Picasso. Exhibition catalogue. 2019.

Bernard Ruiz-Picasso and Alexander S. C. Rower, Confronting the Void

Chus Martinez, No Feeling Is Final

Group Exhibition Catalogue“Calder in France.” Cahiers d’Art, no. 1 (2015). Edited by Alexander S. C. Rower.

Susan Braeuer Dam, Calder in France

Robert Melvin Rubin, An Architecture of Making: Saché and Roxbury

Agnès Varda in conversation with Joan Simon

Magazine, Monograph