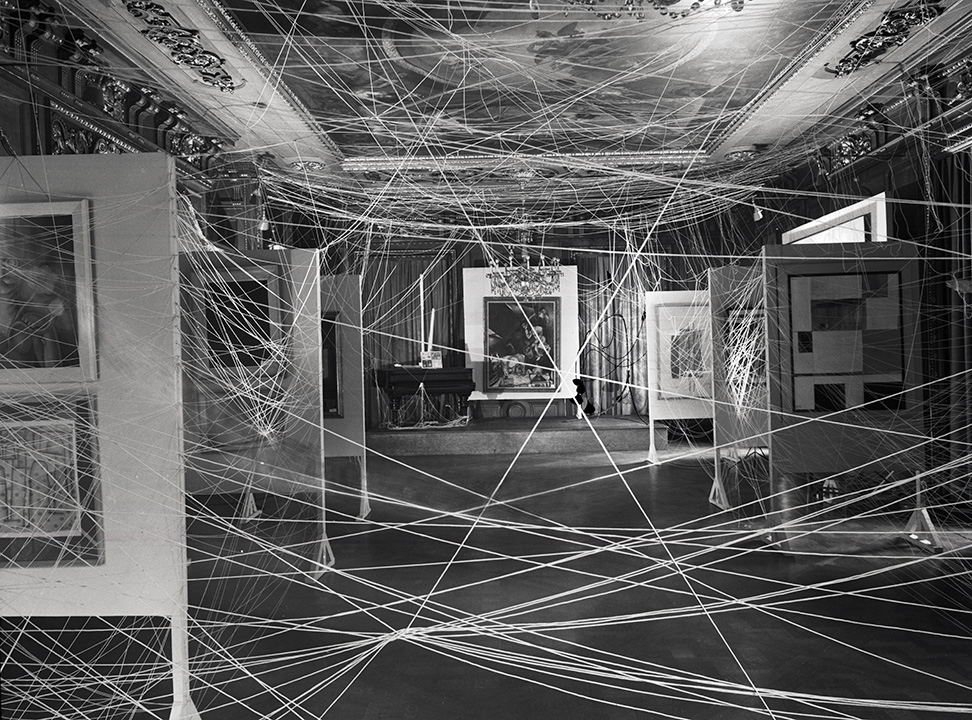

Alexander Calder has often been considered a surrealist. André Breton, the founder of the movement, embraced him and included his sculptures in important surrealist exhibitions, beginning in May 1936 with Exposition surréaliste d’objets at Galerie Charles Ratton, in Paris. Calder’s string and wire mobile at Ratton, made with seven shards of repurposed colored glass and two shell buttons, was installed within the context of African, Eskimo, Oceanic, Peruvian, and pre-Columbian objects, along with mineral and vegetal forms. A month later, Calder partook in the International Surrealist Exhibition at New Burlington Galleries, London. He also contributed to Breton and Marcel Duchamp’s 1942 First Papers of Surrealism at the Whitelaw Reid Mansion, New York, and Le Surréalisme en 1947 at Galerie Maeght, Paris. Yet despite this ongoing involvement, Calder remained unassailably individualistic. Writing to art collector and connoisseur James Thrall Soby in 1936, he hilariously implored that he not be confused with “the Surrealistes, the neo-romanticists, the concretionists, the automobilistes, or the garagistes.”[1]

Of the tenuous ties between Calder and surrealism, there emerges a shared fascination with noble and simple artifacts from world cultures. Calder was somewhat unconcerned with their historic definition––rather, he was drawn to them as aesthetic objects that he often acquired through trades of his own works. Among the pre-Columbian examples in my grandparents’ primary home in Roxbury, Connecticut, was an Aztec Chicomecóatl (c. AD 1500), or goddess of maize, and a bulbous Nayarit seated figure (c. 100 BC–AD 250). My grandfather also gave my grandmother numerous pre-Columbian gold body adornments. Under the Roxbury roof, these artifacts fused with their environment, unifying a sense of place by mysteriously stabilizing the mobiles that hovered spellbound overhead and radiated long-gathered energy. Their simplicity, humanism, and direct use of materials were all qualities that Calder employed in his own radical experiments that effused over the course of six decades.

Calder’s invention of sculpting in wire was brought to maturity in Paris in 1926, marking his “blue period” and precipitating what was to come in twentieth-century art. From the reduced linearity of Elephant (c. 1927) and the extended reach of Helen Wills II (1928) to the near life-size mobility of Aztec Josephine Baker (1930), these works not only upend space through transparent and massless volumes, but also present the reality of movement and gesture through intentionally vibrating wire lines. Aztec Josephine Baker is the ultimate of five renderings in wire of the celebrated cabaret performer that features a dozen jointed articulations. A proto-mobile with suspension, action and fluid movement, the composition captures voids and presents her haughty attitude in space. Calder called his figurative wire works “objects” as opposed to “sculpture” to signify his decisive break from the solidity of clay, bronze, and marble, and his idiosyncratic language was not only groundbreaking but also a prelude of his future capabilities in both abstraction and scale. In 1929, a transformative year in terms of his shift towards abstraction, Calder wrote:

These new studies in wire … are still simple, more simple than before and therein lie the great possibilities which I have only recently come to feel for the wire medium. Before, the wire studies were subjective, portraits, caricatures, stylized representations of beasts and humans. But these recent things have been viewed from a more objective angle and although their present size is diminutive, I feel that there is no limitation to the scale to which they can be enlarged.[2]

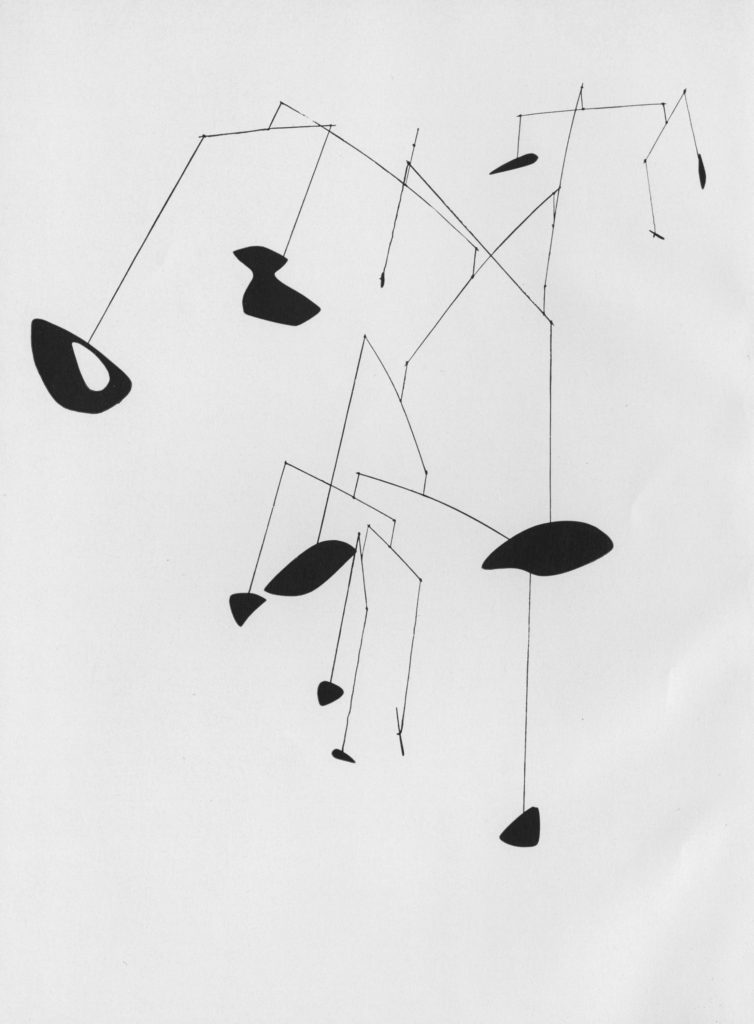

With his invention of the mobile in 1931, so-named by Duchamp (“mobile” ingeniously refers to both “motion” and “motive” in French), Calder further developed the actuality of the fourth dimension realized as present-time experience. Among the earliest nonobjective sculptures that exemplify the mobile’s evolution are those with simple connections suggesting non-final compositions, including Small Feathers (1931) and Object with Red Ball (1931). Formally, Object with Red Ball appears to be a perceptual meditation on the purity of the sphere, comprising a solid red sphere made of wood, an implied black sphere made of two intersecting sheet metal discs, and a hoop as a two-dimensional representation of a large three-dimensional sphere made of steel rod. As the white structure melds with the wall beyond, the three spheres are left in an otherworldly realm. Yet what is most remarkable is something that often goes unnoticed: intervention by the viewer is intrinsic to this work, which was a radical idea in 1931, and still today. The red and black spheres that hang along the upper horizontal rod are unfixed and repositionable, and the vertical white post, which is held upright by a thick internal pin, can be rotated anywhere in 360 degrees. “What was Calder’s original composition?” is a question that I am often asked. My grandfather’s point was to leave this open to the viewer, intentionally prescribing no preference for the definitive form. “When I have used spheres and discs,” wrote Calder, “I have intended that they should represent more than what they just are … A ball of wood or a disc of metal is rather a dull object without this sense of something emanating from it.”[3] Calder’s use of discs, spheres, and orbs, many of which appear throughout this exhibition, were not representations of the sun, moon, earth, or any such aspect of the observable universe. Rather, as empyrean forms that indicate spatial delineations of energies, they were not intended as a definition for the universe, but rather the universal—an exploration of the unifying force postulated by physicists today as string theory.

At the time of the first mobile’s appearance, Calder bestrode the line between calling himself a painter and a sculptor. Although his initial venture into abstraction was with oil paintings—a medium that he returned to periodically throughout his career—he quickly gained recognition as an artist in wire and sheet metal. As part of a statement for a group exhibition in 1933, he called into question the validity of two-dimensionality on canvas:

The sense of motion in painting and sculpture has long been considered as one of the primary elements of the composition. The Futurists prescribed for its rendition. Marcel Duchamp’s “Nude descending the stairs” is the result of the desire for motion. Here he has also eliminated representative form. This avoids the connotation of ideas which would interfere with the success of the main issue—the sense of movement … Therefore, why not plastic forms in motion?[4]

When Calder created Untitled (c. 1932), one of the earliest of his free-hanging mobiles, he likely conceived of it as a three-dimensional materialization of his two-dimensional abstractions. With a twelve-foot span of white lumbering spheres in wood and a contrapuntal red orb, this dramatic mobile engages a large area of surrounding space. As Calder continued to work with hanging constructions, primarily in sheet metal, he incorporated themes that resurfaced throughout his career, such as the expression of separate yet symbiotic motions, the reflexive relationship between negative and positive space, and the possibility of scale.

In the mid-1930s, Calder worked prolifically on panels and frames that explored the concept of two-dimensional paintings, yet in actual motion. In works such as Snake and the Cross (1936), White Panel (1936), and Red Panel (1936), elements oscillate in front of a defined area of a colored plywood panel or within a wooden frame. Viewed head-on, these spirited sculptures appear to be paintings whose compositions flash form and color, blurring the lines between fixedness and circumstance and activating a complex choreography of nonobjective forms. In White Panel, the biomorphic components occasionally collide at unpredictable moments, instigating curiously upsetting vanguard music, which can shock the viewer into present time.

French philosopher Jean-Paul Sartre once wrote of Calder’s practice, “If it is true that the sculptor is supposed to infuse static matter with movement, then it would be a mistake to associate Calder’s art with the sculptor’s … It is not his aim to entomb it forever in bronze or gold, those glorious, stupid materials doomed by their nature to immobility.”[5] Beyond his pioneering use of industrial materials, my grandfather had a deep respect for humble ones. With works like Tree (1941), composed of an eight-foot-tall fixed base from which floats a delicate mobile, Calder breathed new life into bits of cast-off objects that in turn express themselves independently, as seen in the glass and mirror fragments that refract and reflect radiance. “Not extractions, but abstractions,” Calder once wrote. “Abstractions that are like nothing in life except in their manner of reacting.”[6] Neither imitations nor abstractions of the natural world, Calder’s mobiles maintain a parallel reality.

The use of honest materials extended into Calder’s jewelry making, as well. He began creating jewelry as early as 1906 for his sister’s dolls using copper wires that had been discarded in the streets of Pasadena, California. This homegrown sensibility continued throughout his multifaceted career. Each of my grandfather’s pieces, from necklaces and brooches to hair combs, is a unique design made of brass or silver wire, ceramic fragments, even bones and broken automobile taillights. The necklace Caged Crockery (c. 1945) offers a sharp insight into his sensibilities, often stirred by the caprices of nature. It is made from a nineteenth-century Chinese porcelain plate depicting a carp that likely came from Calder’s parents, both of whom were fascinated with the Orient. The plate was broken during a meal at home, and Calder preserved the fragments by respecting the forms caused by the accident. He caged these five amulets in silver wire, leaving the fish image lost in abstraction. Calder also funneled forms and symbols from ancient sources, including spirals and figas, and in doing so he connected the wearer to primeval forces. His intuitive process can be seen through hammer marks on the flattened wire, a rarefied display of his confident technique. In the present exhibition, my grandfather’s jewelry welcomes visitors into the first gallery in the manner that conveys the intimacy of the pre-Columbian jewelry he gave to my grandmother.

During the years around World War II, when sheet metal and especially aluminum was in short supply, Calder created exquisite albeit eccentric constructions of carved wooden forms connected at emotional distances by wires. This series was christened “constellations” by curator James Johnson Sweeney and Duchamp. “They had a suggestion of some kind of cosmic nuclear gases—which I won’t try to explain,” Calder recalled. “I was interested in the extremely delicate, open composition.”[7] For his constellations, Calder carved directly in a multitude of wood varieties, a practice he began in the mid-1920s with his figurative works, and one that flourished in the 1930s and 1940s as he created nonobjective forms for sculptures at once agile and refined, yet still primitive. With their disparate shapes and uniting wires, works such as Wall Constellation with Row of Objects (1943) seem poised for action, yet weightlessly. Expanding beyond the frame and panel works of the 1930s, which are hung and viewed precisely in the manner of a painting, the constellations are often mounted at surprising moments on the wall, with a height dictated by the angles of their protrusions.

At the core of Calder’s entire enterprise was an engagement with perceptual conditions. “A mobile in motion leaves an invisible wake behind it, or rather, each element leaves an individual wake behind its individual self,” wrote my grandfather in 1943. “Sometimes these wakes are contracted within each other, and sometimes they are deployed.”[8] On view is Boomerangs (1941), a mobile that comprises large loops of wire creating chains from which hang polychromatic elements. This chain link technique was first used in Lobster Trap and Fish Tail (1939), commissioned for the principal stairwell of the Museum of Modern Art, New York (MoMA). From certain vantage points the chains recede from view, rendering forms that seem to float in space and, in the case of Boomerangs, occasionally strike one another with intended sonorous consequences. “To me,” Calder wrote, “the most important thing in composition is disparity.”[9] Continuing an intuition born in the 1930s with works like White Panel and others, Calder used the immaterial phenomenon of sound in Boomerangs, as he did color, form, and size, as a means to enhance disparity within a composition.

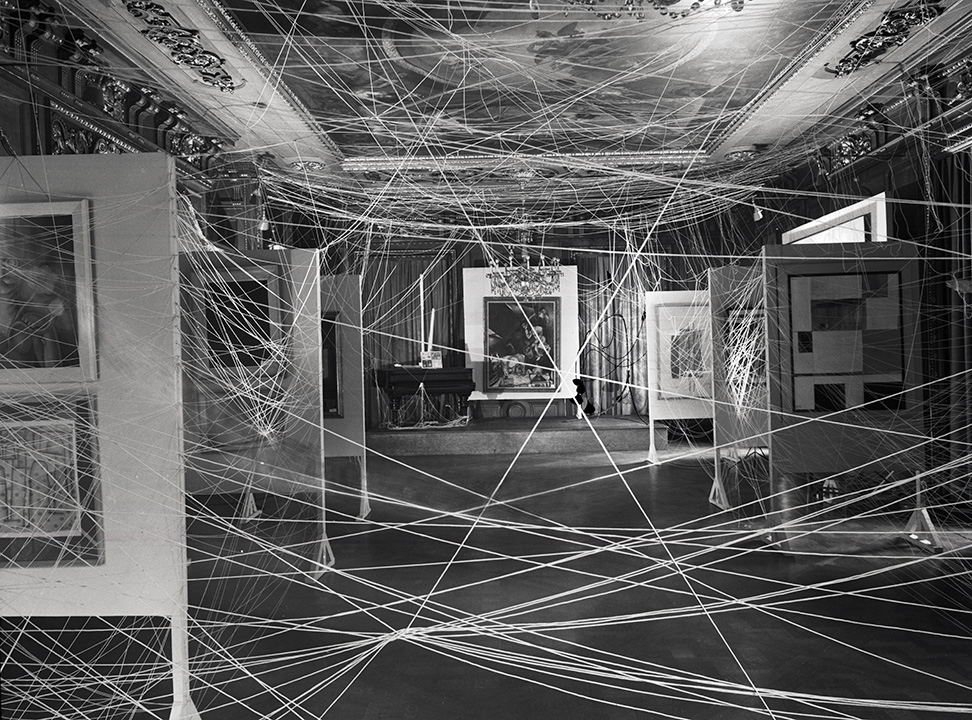

Calder went on to explore thresholds of presence and absence on multiple levels. In ‘53 Black Dots (1953), he pierced three of the twelve elements of the mobile, redefining its ever-shifting encampment of space and recalling his statement from the decade prior, “For though the lightness of a pierced or serrated solid or surface is extremely interesting the still greater lack of weight of deployed nuclei is much more so.”[10] Its black sheet metal elements are constantly appearing and disappearing as they spin on their threads, and the smallest element seems to spring from one of the pierced voids as it navigates an orbit around the main composition, occasionally interacting with other forms. Named for the year in which it was created, ‘53 Black Dots was completed before the Calder family embarked for a yearlong sojourn in Aix-en-Provence, and it was included in the monographic Calder presentation curated by MoMA for the 1953 São Paulo Biennial. This extraordinary mobile was conceived as a larger version of Black Dots (1941, Art Institute of Chicago) which premiered in Calder’s seminal 1943 MoMA retrospective and also served as the frontispiece for the accompanying catalogue in a striking Herbert Matter photograph, exemplifying Calder as the new modernity.

Some two decades after contemplating the notion of size in his 1929 statement on wire sculpture, Calder began to execute projects on a monumental scale for international commissions, a practice that gained momentum in the late 1950s. In realizing these works, Calder devised a process of “sketching” an initial concept directly in sheet metal by making maquettes from which he could proportionately enlarge his sculptures. Thirteen maquettes of varying size and refinement are on view in this exhibition, the earliest of which is the sublime Untitled (maquette, 1939), made just three years after Calder first employed the maquette-making technique. Among the later works is El Sol Rojo (maquette), made in October 1967 at Calder’s studio in Saché, France, which is a humble beginning for the titan that now stands at over eighty feet tall. El Sol Rojo remains his tallest stabile, whose peaks and punctuality have stood in Mexico City providing vibrant contrast to the Aztec Stadium for the past half-century.

In 1949, Duchamp summed up the Calder revolution when he wrote:

Among the “innovations” in art after the First World War, Calder’s approach to sculpture was so removed from the accepted formulas that he had to invent a new name for his forms in motion. He called them mobiles. In their treatment of gravity, disturbed by gentle movements, they give the feeling that “they carry pleasures peculiar to themselves, which are quite unlike the pleasures of scratching,” to quote Plato in his Philebus. A light breeze, an electric motor, or both in the form of an electric fan, start in motion weights, counter-weights, levers which design in mid-air their unpredictable arabesques and introduce an element of lasting surprise. The symphony is complete when color and sound join in and call on all our senses to follow the unwritten score. Pure joie de vivre. The art of Calder is the sublimation of a tree in the wind.[11]

Museo Jumex, Mexico City. Calder: Discipline of the Dance. 21 March–28 June 2015.

Solo ExhibitionHauser & Wirth, Los Angeles. Calder: Nonspace. Exhibition catalogue. 2019.

Andrew Berardini, The Cosmic Mathematics of Alexander Calder

Solo Exhibition Catalogue“Calder in France.” Cahiers d’Art, no. 1 (2015). Edited by Alexander S. C. Rower.

Susan Braeuer Dam, Calder in France

Robert Melvin Rubin, An Architecture of Making: Saché and Roxbury

Agnès Varda in conversation with Joan Simon

Magazine, MonographAlmine Rech Gallery, New York. Calder and Picasso. Exhibition catalogue. 2016.

Robert Slifkin, The Mobile Line

Susan Braeuer Dam, Liberating Lines

Jordana Mendelson, Picasso, Miró, and Calder at the 1937 Spanish Pavilion in Paris

Group Exhibition Catalogue“Calder in France.” Cahiers d’Art, no. 1 (2015). Edited by Alexander S. C. Rower.

Susan Braeuer Dam, Calder in France

Robert Melvin Rubin, An Architecture of Making: Saché and Roxbury

Agnès Varda in conversation with Joan Simon

Magazine, Monograph