I ran my circus once + Vogue (here) asked me to come to their studio + let them make photographs—so I did + then I ran it again in their studio. But since then I have shut up the show and am going to leave it there for a long time as it hinders my work. There is a very fine bronze foundry at the end of Villa Brune—so I am soon going to delve into cire perdue.

I have been carving, and painting a bit, and

am really getting underway.

–Alexander Calder[1]

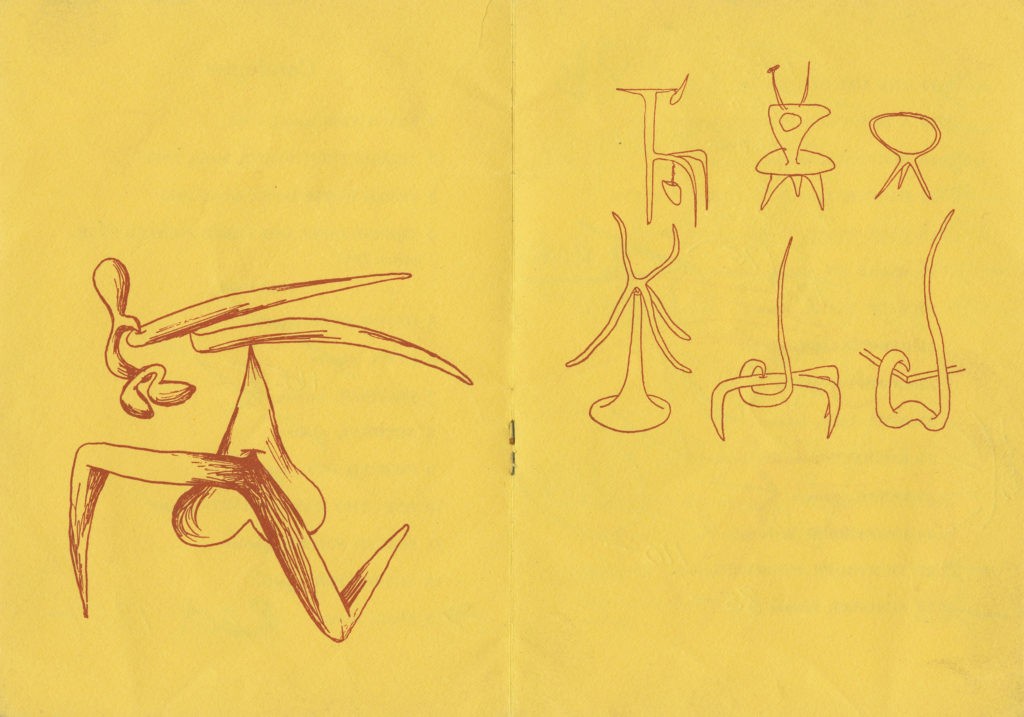

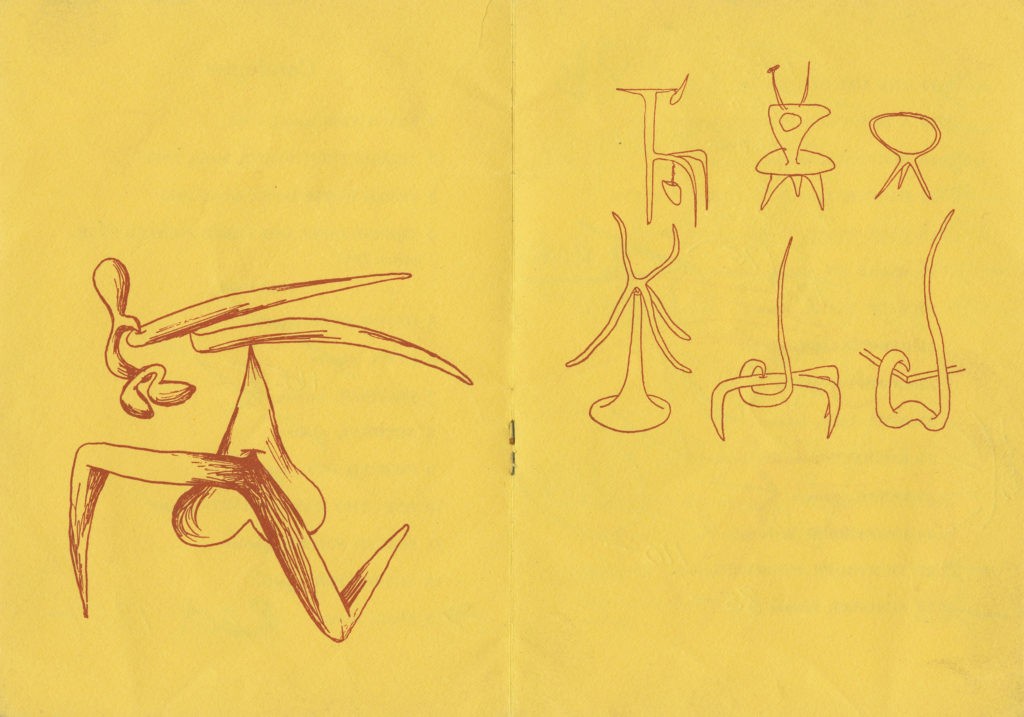

My grandfather’s creative process was intuitive and direct, and his work in bronze was no exception. For his first foray into the medium in 1930, he tried divining action out of stationary mass. A master of anatomy who knew how to make beautiful objects, Calder obviously and convincingly shied away from the beauty of the figure and made works about action or its ill aftereffects. The two most exciting of the group are Pieds en l’air and Tête par terre, both of which depict the moment of impact after a fall. In Pieds en l’air, the action is defined by the figure on her back, with two legs jutting awkwardly in the air and arms and hair being roughly thrown back onto the ground. In Tête par terre, the figure is wretchedly distorted, with his face planted flat on the ground. In addition, we find sad horses, a forlorn cow and donkey, a malnourished cat, and an abused elephant.

Instead of wax or clay, which remain pliable indefinitely, Calder chose to work directly in plaster, which has a brief workable time frame. As the son and grandson of master bronze sculptors, he was intimately familiar with conventional techniques; his decision to work in such an immediate way—to mold his materials in the half-life, somewhere between a soupy mess and solidified crystals—was deliberate. Formed, squeezed, and cajoled by my grandfather’s hands in a matter of minutes, the 1930 plasters all have visible fingerprints that add to their intimate complexion.

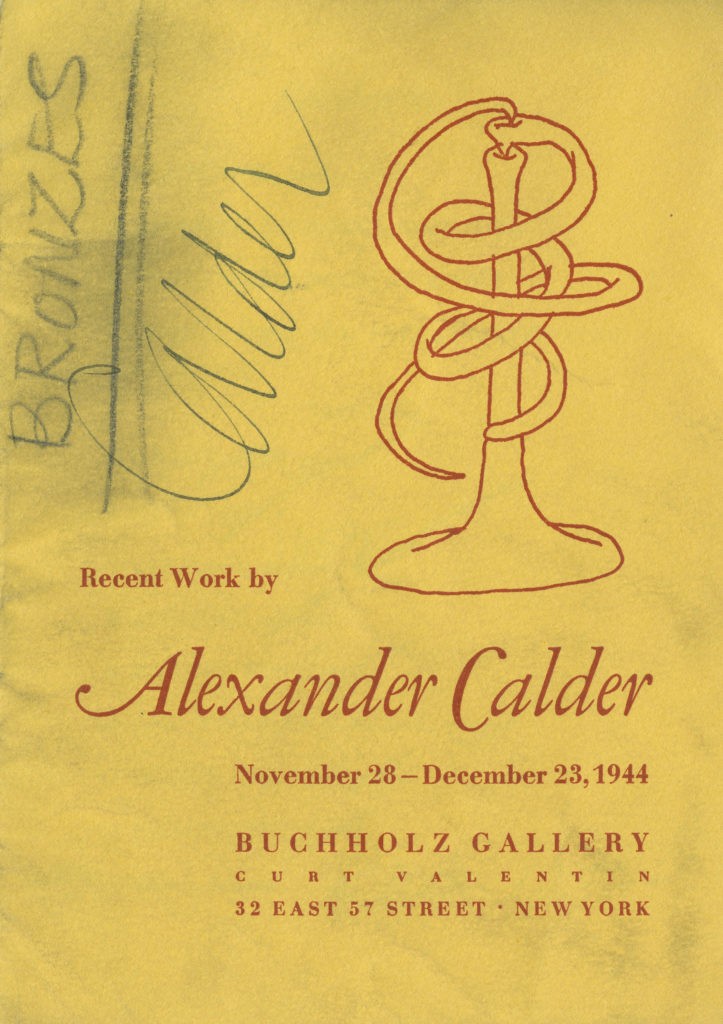

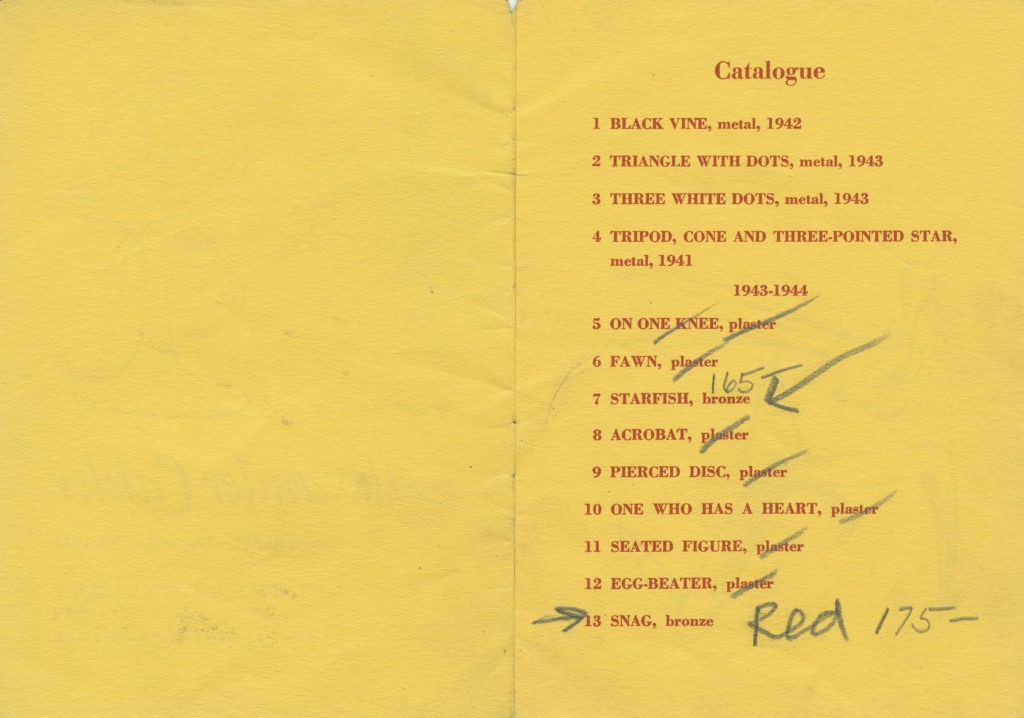

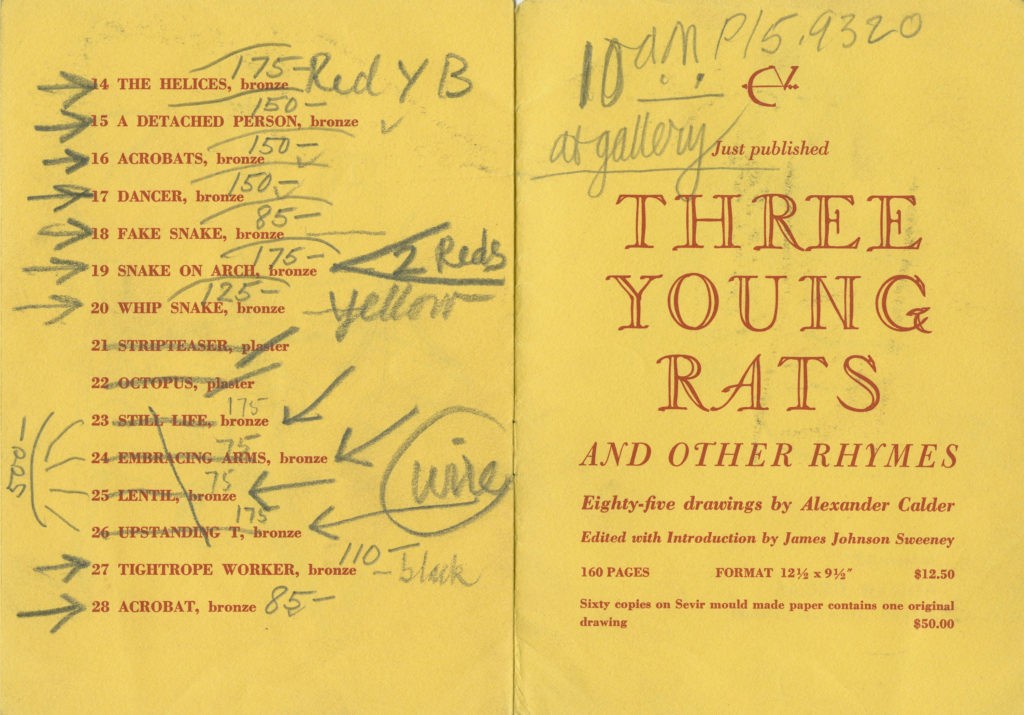

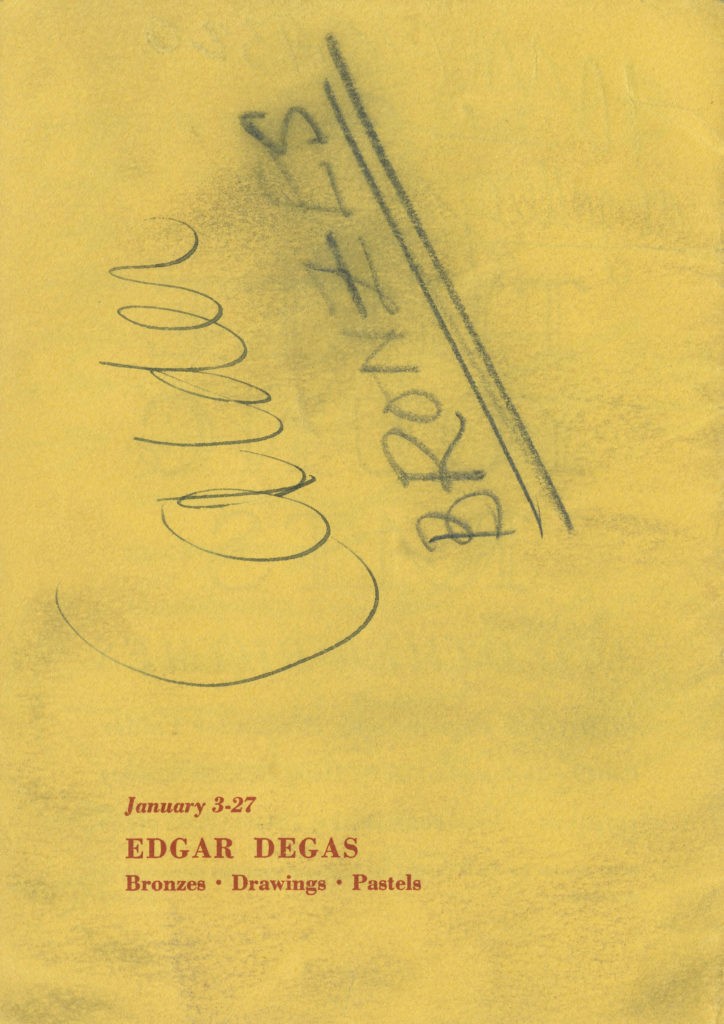

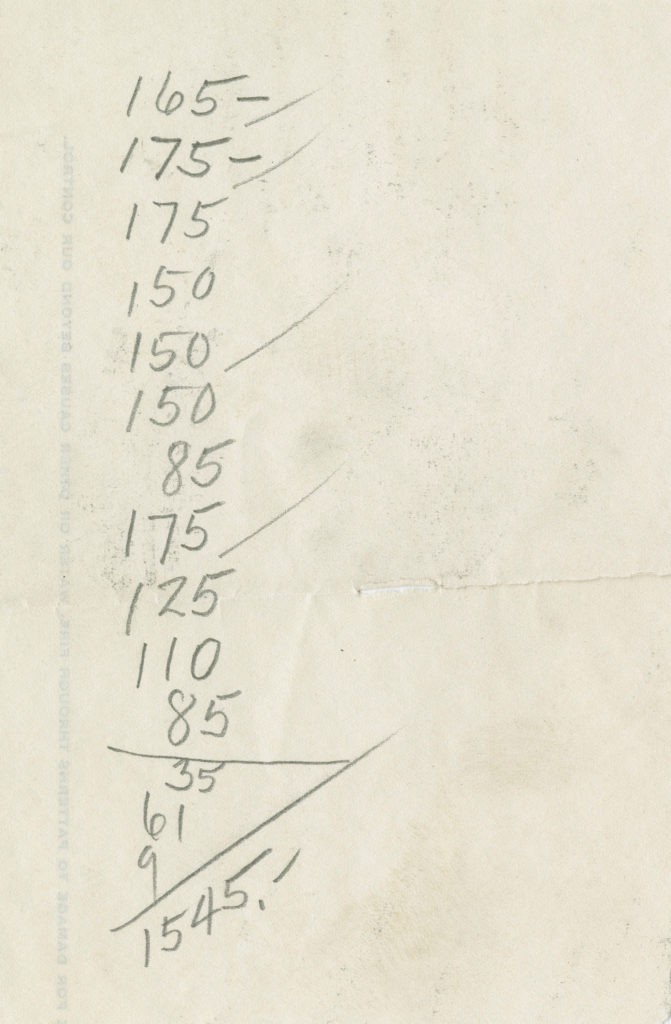

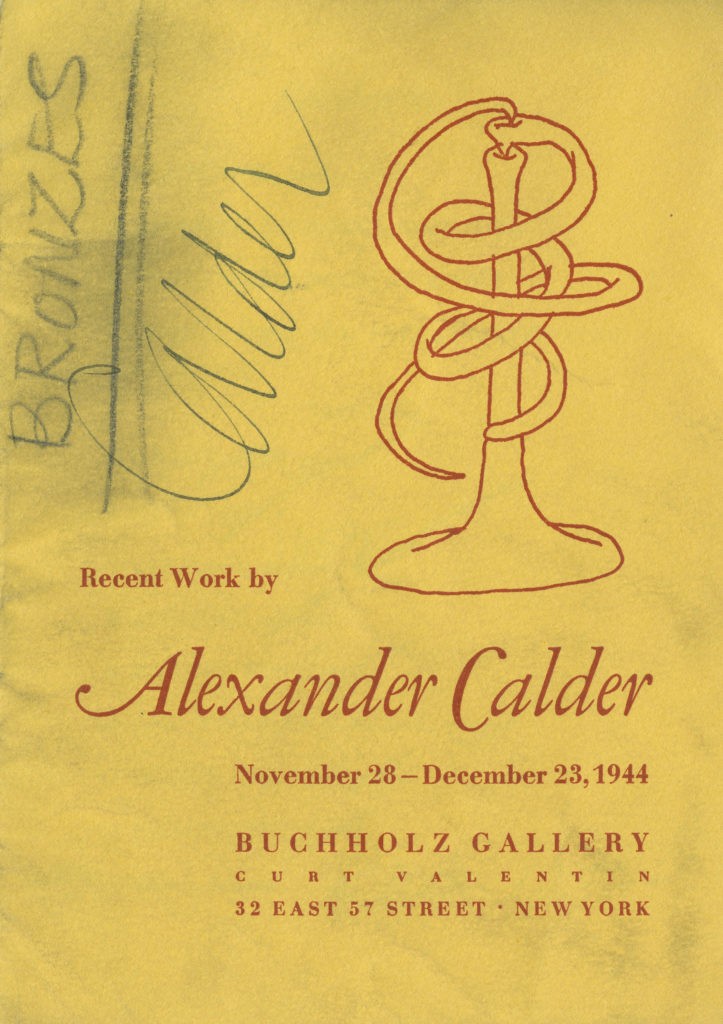

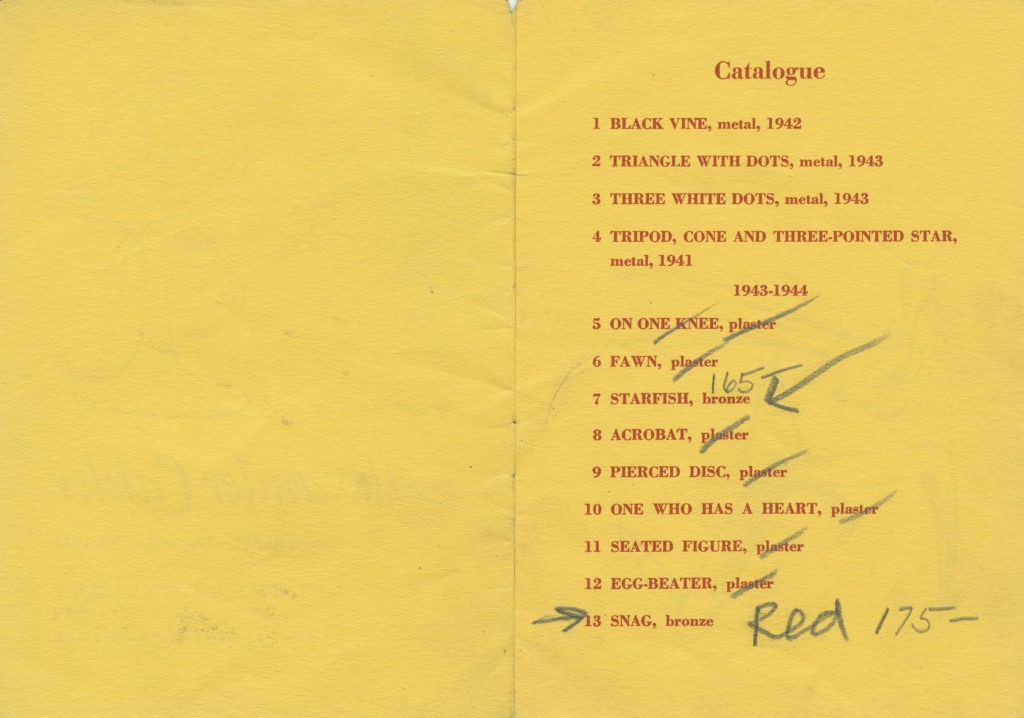

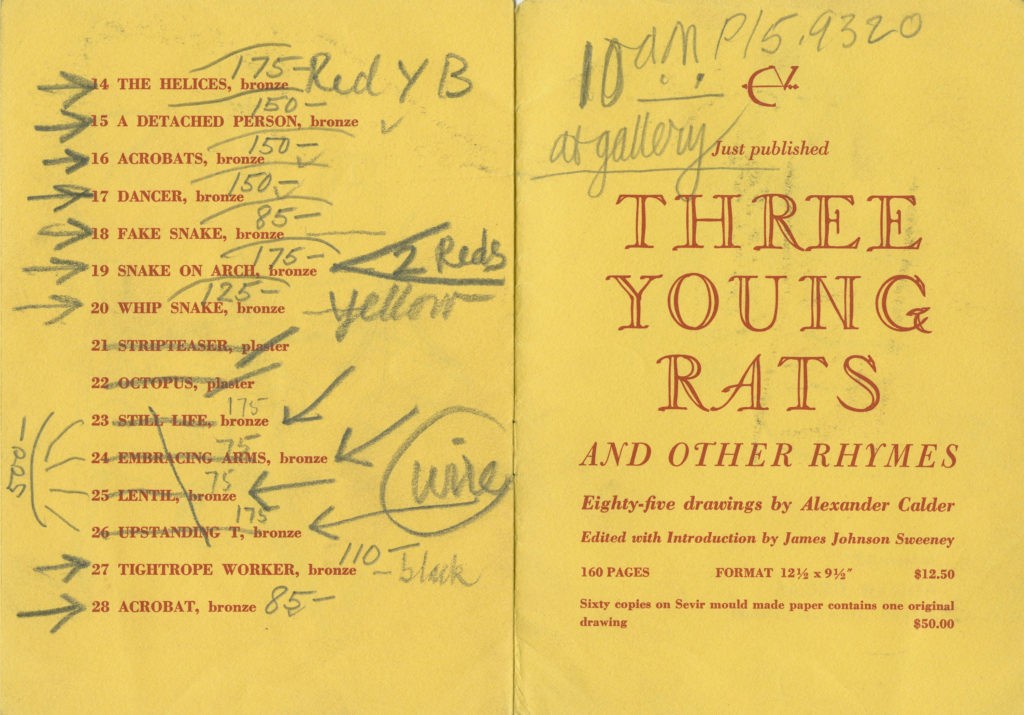

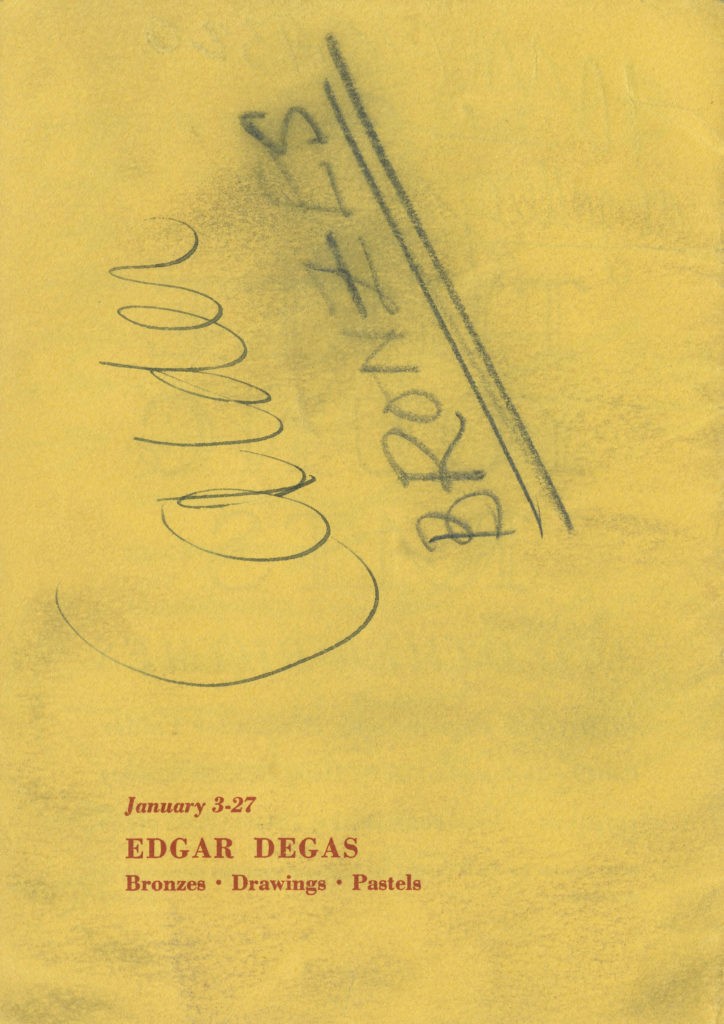

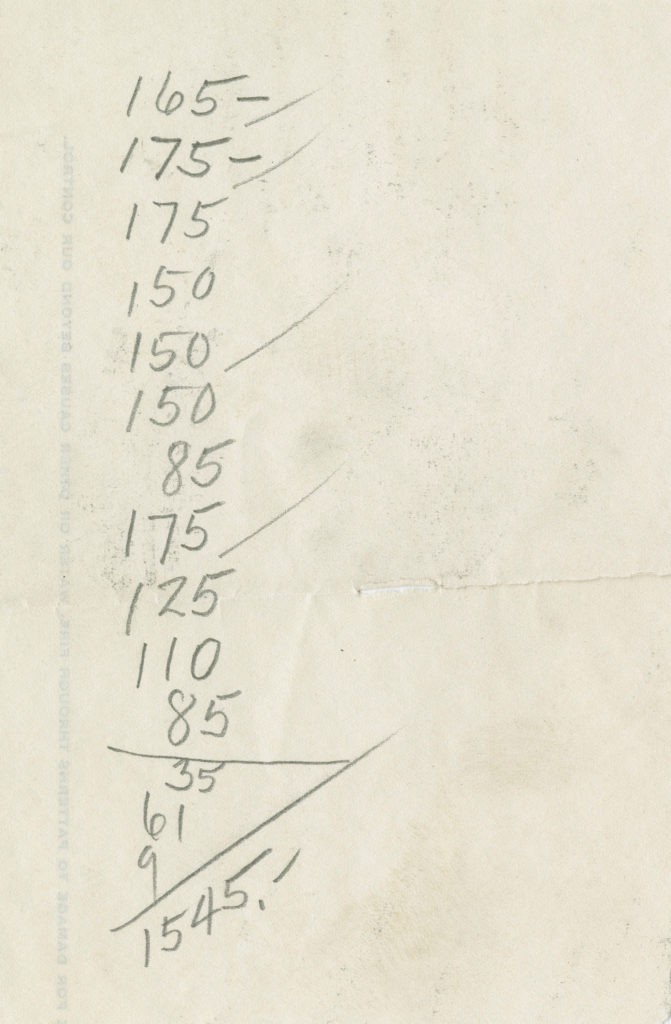

In the spring of 1944, the architect Wallace K. Harrison suggested that Calder sculpt large outdoor works in concrete for an International Style architectural project. As Calder recalled in his autobiography, “Wally Harrison had suggested I make some large outdoor objects which could be done in cement. He apparently forgot about his suggestion immediately, but I did not and I started to work in plaster. I finally made things which were mobile objects and had them cast in bronze—acrobats, animals, snakes, dancers, a starfish, and tightrope performers.”[2] In November of that year, Buchholz Gallery/Curt Valentin in New York devoted its first Calder exhibition to these modeled forms in plaster and bronze. The artist’s illustrations of the sculptures—along with handwritten prices and notes—can be seen in the annotated catalogue from the Calder Foundation’s archives.

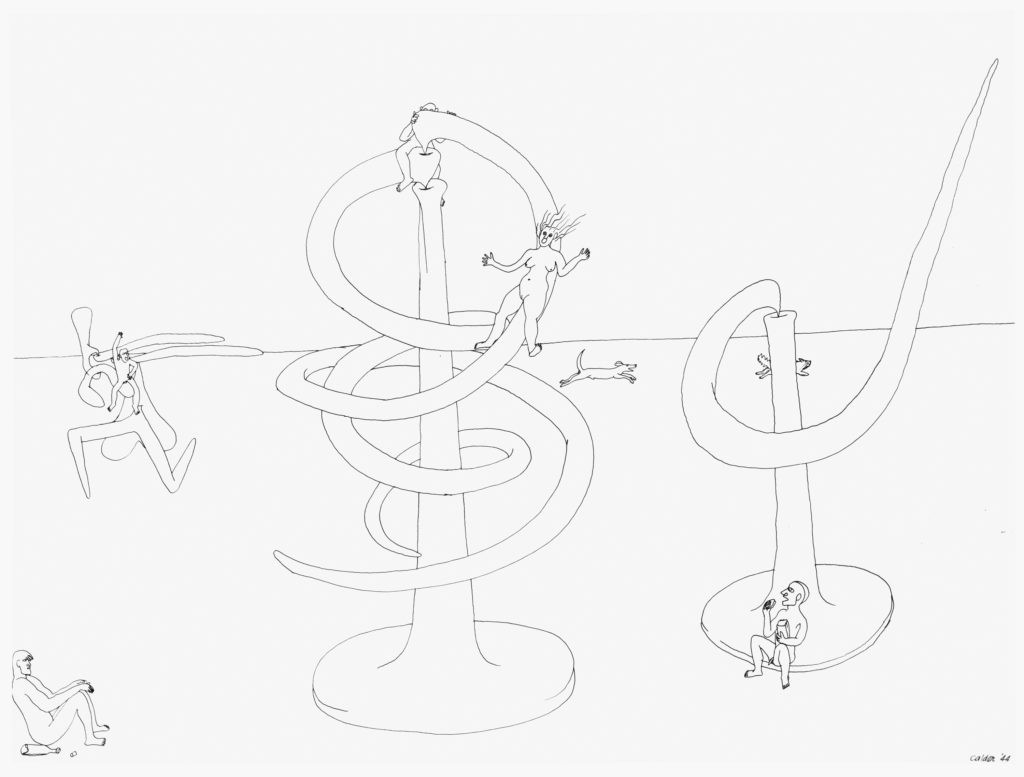

It is critical to remember that these handsome bronzes of 1944 were not intended for a domestic setting, nor were they conceived on a human scale. Instead, they were envisioned as giant monuments to exist some 30 or 40 feet tall. Try to imagine how imposing On One Knee would have been in modern concrete with its six separate and balanced sections as huge lumbering forms, gesticulating high above. Considering its size and the fact that it was contemporaneously cast in aluminum, On One Knee was likely the work that Calder chose for Harrison’s approval. A sense of the scale Calder envisioned for the works can be divined from drawings in which humans and animals frolic on his bronzes.

In 1943, Calder ruminated, “A knowledge of, and sympathy with, the qualities of the materials used are essential to proper treatment … Bronze, cast, serves well for slender, attenuated shapes. It is strong even when very slender.”[3] A year later, Calder stretched the medium to its limits. In Egg-Beater, Calder devised a way to make bronze permeable with undercut forms of string, wire, and coatings of plaster that technicians then had to somehow figure out how to cast. In kinetic works such as The Helices, the tremendous extension of the lines without additional structure allows two helixes to balance on point such that they can rotate in syncopation or opposition. A recently discovered photograph from 1944 attests to the sheer range of experimentation in plaster that took place during this time. Atop the piano in his jam-packed Roxbury studio rests a forest of plasters, a tangled mass of elongated extremities.[4]

While Calder’s experimentation in bronze began with convenience—the Fonderie Valsuani, located at 74 rue des Plantes, was only 120 meters from his studio at 7 Villa Brune in Paris—it ended with an irrepressible exploration of stretching, pulling, and layering the medium. Recalling his 1944 bronzes, Calder remarked, “This was rather an expensive venture and did not sell very well, so I abandoned it for my previous technique. It was also disagreeable to have to check the manipulations of some other person working on the objects at the foundry. However, I play with the idea, from time to time, of going back to this medium.”[5]

Hauser & Wirth, Los Angeles. Calder: Nonspace. Exhibition catalogue. 2019.

Andrew Berardini, The Cosmic Mathematics of Alexander Calder

Solo Exhibition CatalogueAlmine Rech Gallery, New York. Calder and Picasso. Exhibition catalogue. 2016.

Robert Slifkin, The Mobile Line

Susan Braeuer Dam, Liberating Lines

Jordana Mendelson, Picasso, Miró, and Calder at the 1937 Spanish Pavilion in Paris

Group Exhibition Catalogue“Calder in France.” Cahiers d’Art, no. 1 (2015). Edited by Alexander S. C. Rower.

Susan Braeuer Dam, Calder in France

Robert Melvin Rubin, An Architecture of Making: Saché and Roxbury

Agnès Varda in conversation with Joan Simon

Magazine, MonographMuseo Jumex, Mexico City. Calder: Discipline of the Dance. Exhibition catalogue. 2015.

Alexander S. C. Rower, Calder: Discipline of the Dance

Solo Exhibition Catalogue