Although Calder was at the table in Paris with Duchamp, Mondrian, and the others when modern art was cooked up there, it is the French village of Saché, rather than any Parisian landmark, that is his lieu de memoire. Here he found, then created, a comfortable rural environment in which to live and work. His interventions in the landscape—a scratch-built studio and, eventually, a house—went far beyond what he had done in Roxbury, Connecticut, two decades earlier. They were of a piece with his more monumental late postwar creations, yet never out of sync with the rhythms and textures of the tiny village in the Touraine they overlooked. If Le Carroi (the name of Calder’s domain) qualifies as a total work of art, it is a gentle and modest one—if a modest Gesamtkunstwerk is not an oxymoron. Yes, Calder moved earth and drew an entire building. He even made a Calder sculpture for the village square. But the effect is the opposite of what Adolf Loos lampoons in his famous anti-Gesamtkunstwerk parable “The Story of the Poor Little Rich Man,” in which an architect scolds his client for wearing specially designed bedroom slippers in the living room.[1] Chez Calder, it didn’t work that way. In any case, there was no architect, except when one was needed to sign the paperwork.

Saché, a tiny village in the Touraine that had about six hundred residents when Calder first showed up, is best known as the home of Balzac. Calder was more like a character out of Rabelais, but no matter. He made himself at home there. Today you can get there from Paris on an express train in a bit more than an hour. Back then, it was more remote—at least twice as long a trip from Paris as Roxbury was from New York. As Calder grew older, the distance suited him more and more.

Calder’s implantation in Saché was via his future son-in-law Jean Davidson, whose father had a place there. In the early fifties, Jean bought Moulin Vert, a mill on the Indre River. The Calders dropped in to visit on their way to Brittany (where they would eventually buy a small vacation house). Calder recalls in his autobiography how, while throwing himself headlong into the preparations for Jean’s grand opening festivities, he realized they had provisions for forty people but no cooking implements. He rigged up an improvised grill and rotisserie in order to grill chickens over an open fire:

So I hunted around the unloved house on the other island and found an old garden chair made completely of iron. I wove some wire across where the back had been, and we cocked it up on the fire and it served very well as a grill. Steak à la chaise came to be the spécialité maison. The chickens I throttled each with a piece of wire, the other end of which I attached to a long slender piece of firewood standing on the ledge and leaning against the chimney wall. Thus, the chickens dangled close to the fire.[2]

Calder recalls in his autobiography how enamored he was of the three-story structure with its loft-like open spaces, which Jean had acquired along with some unspecified number of adjacent houses in the village. But it was another abandoned structure that particularly caught his eye. When he first entered François Premier (so named by the locals for its Renaissance details), it was coup de foudre—Calder’s relationship to his real estate was always love at first sight. He would later recall that it had a “fantastic cellarlike room with a dirt floor and wine press set in a cavity in the hillside rock.” No doubt it reminded him of the cellars of his family’s homes, which had been assigned to him as his own workshops when he was younger. Calder’s immediate reaction to this troglodytic paradise: “I will make mobiles of cobwebs and propel them with bats.”[3]

He bartered his artwork for the property. Jean already owed him money for some pieces he had purchased, so Calder just threw a few more on the pile and they called it all square. Since Jean hadn’t even understood that the house Calder wanted had come with the mill, it was an easy deal all around. Calder would make two small studios within a few steps of the house: an atelier des maquettes and the gouacherie. Calder continued to use both on a daily basis even after the new structure up the hill was completed. And Jean would eventually marry Calder’s daughter in a simple ceremony in Saché.

In reading Calder’s autobiography—which is in fact a series of recollections recorded by Jean—I was struck by his permanent state of enchantment with found and recovered objects. Sometimes his reaction was to take these objects and turn them into art, while preferring to call them something else. Sometimes it was to make useful stuff for his personal environments, like kitchen utensils or furniture. Sometimes that useful stuff rises to the level of what we could call architecture. After all, architecture, like art, exists less in a clearly bounded, sacral domain than on a continuum with, or as an insertion into or a riff on, the fabric of life itself. An important aspect of Calder’s modernity lies in his intuitive understanding of this, and also in his resistance to the critical taxonomies by which we pigeonhole things for our own mental safety and convenience. His friend Jean Prouvé once famously said that there is no difference between a chair and a building. Calder took that line of thinking one step further: There is no difference between a chair and a grill.

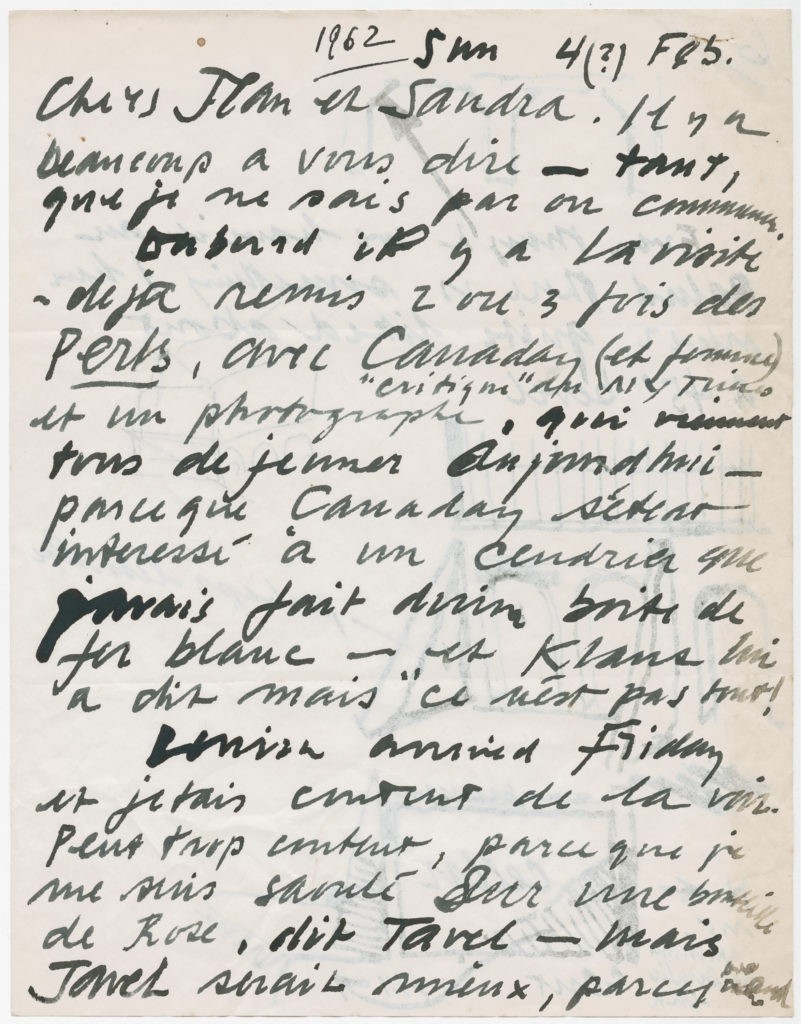

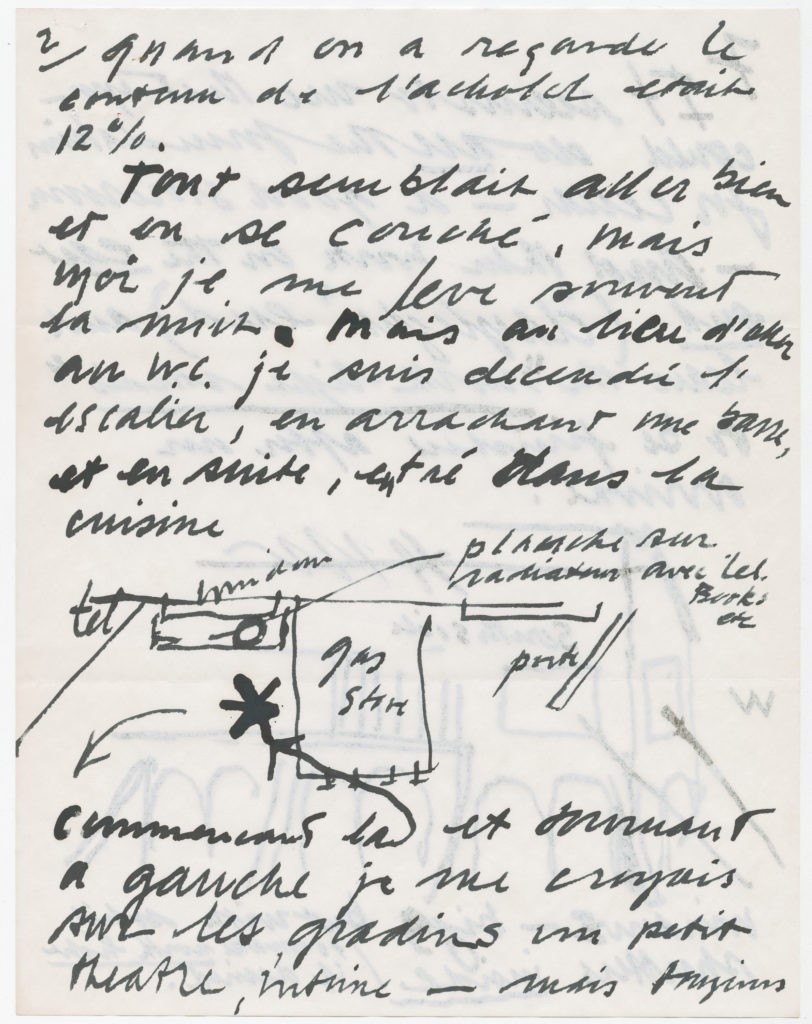

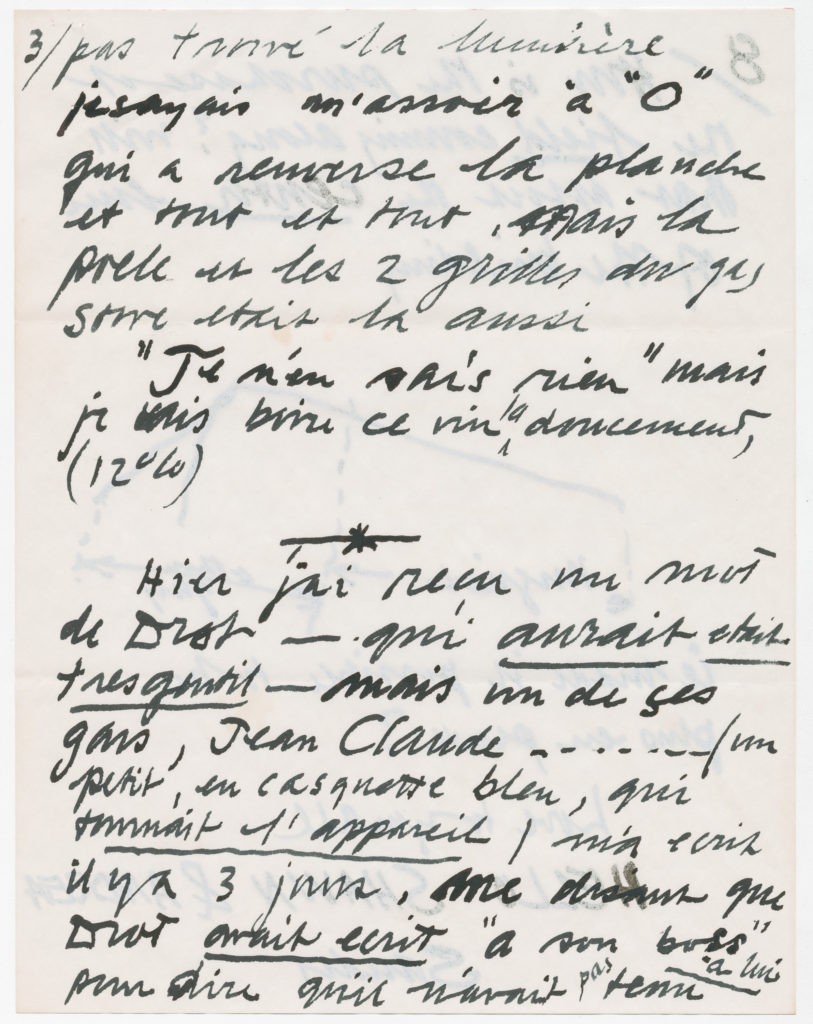

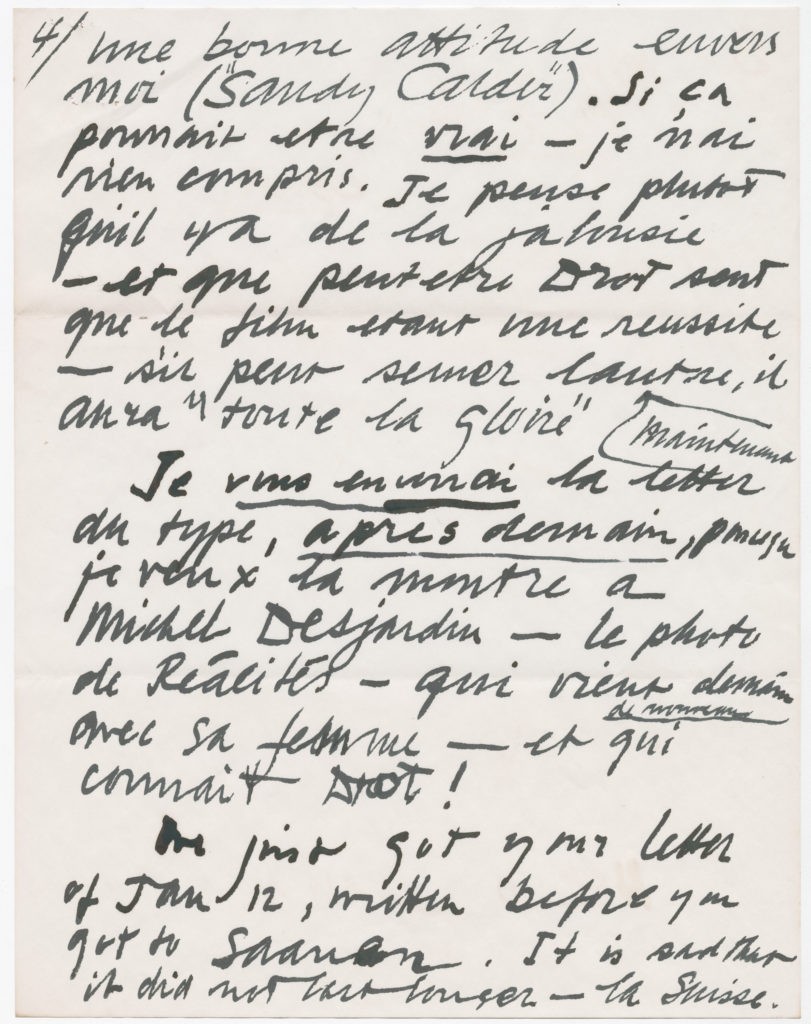

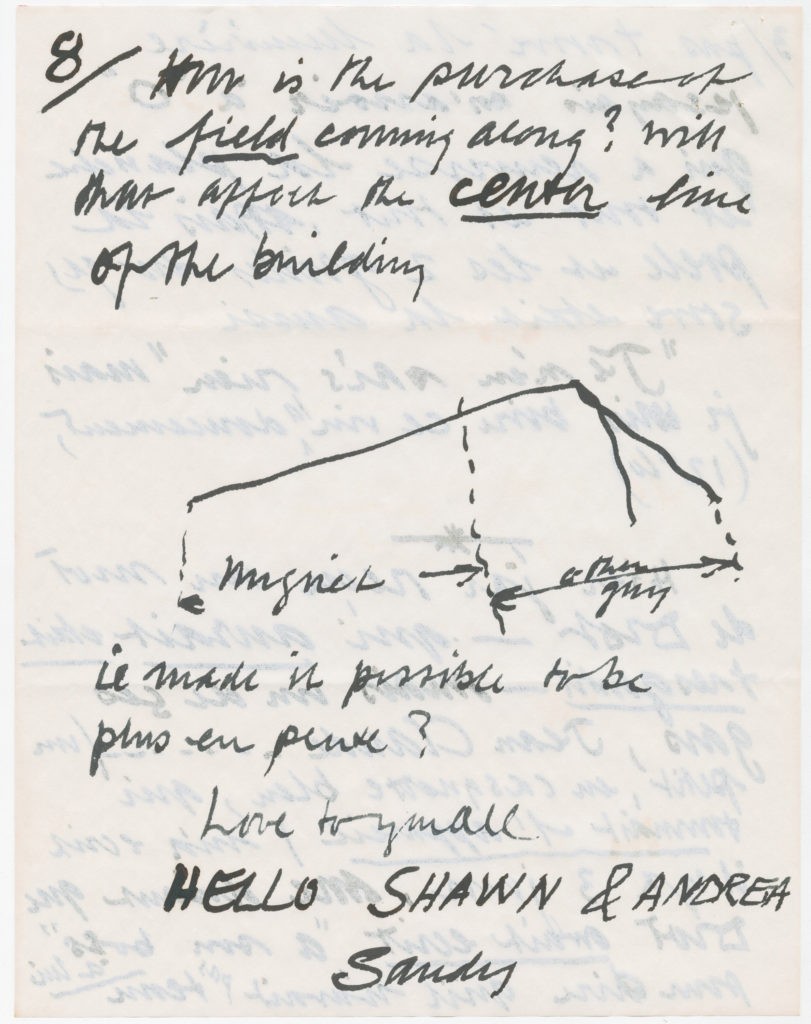

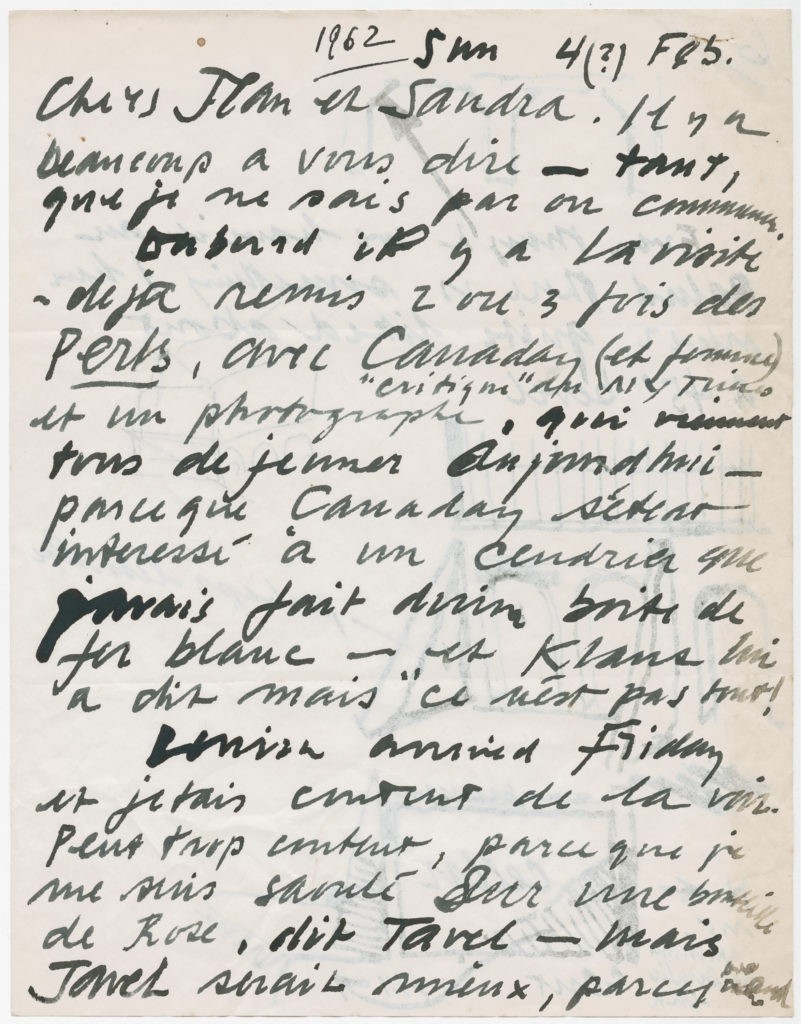

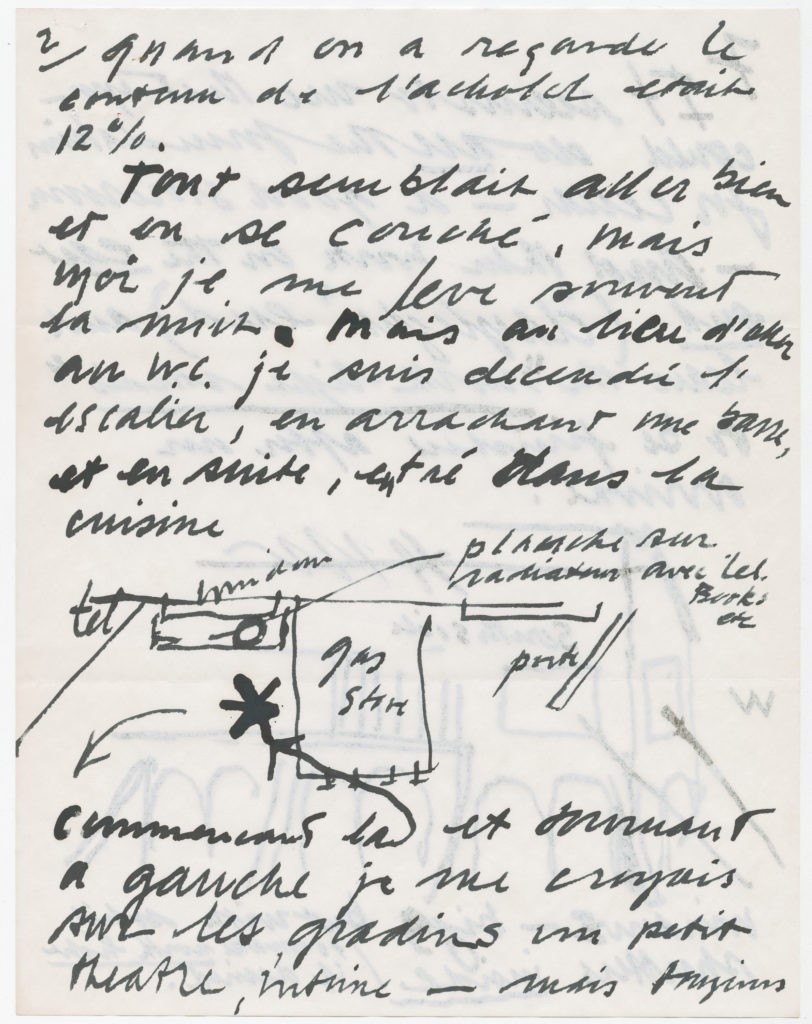

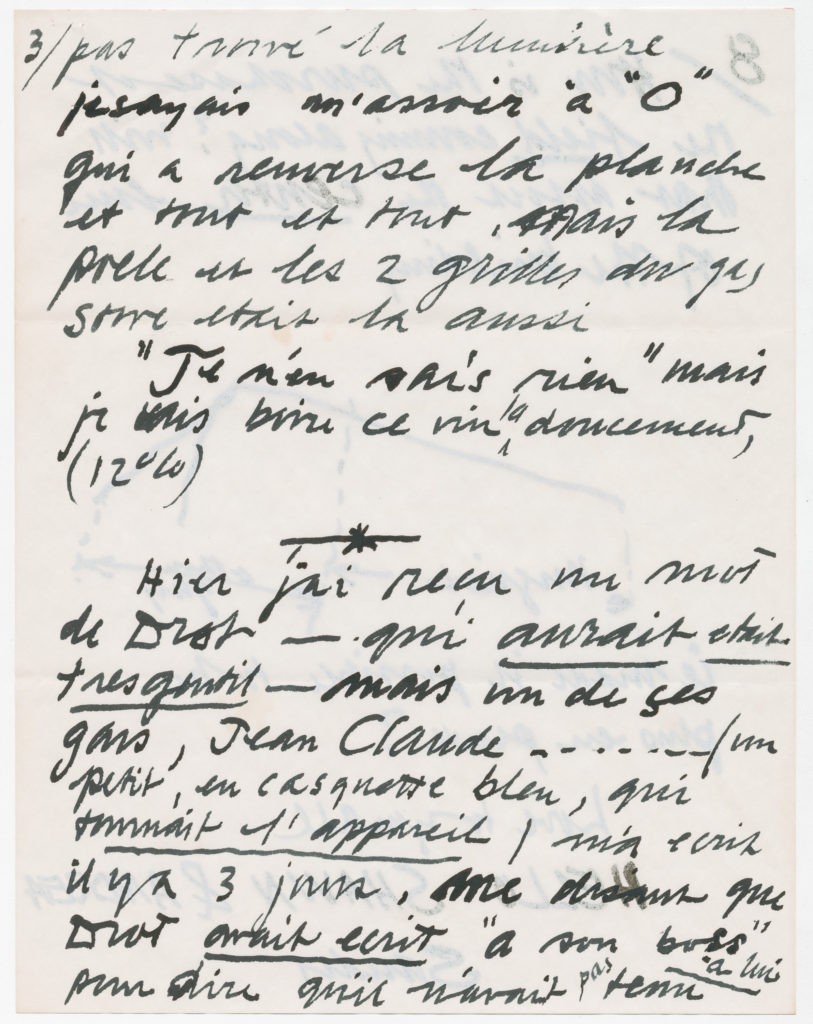

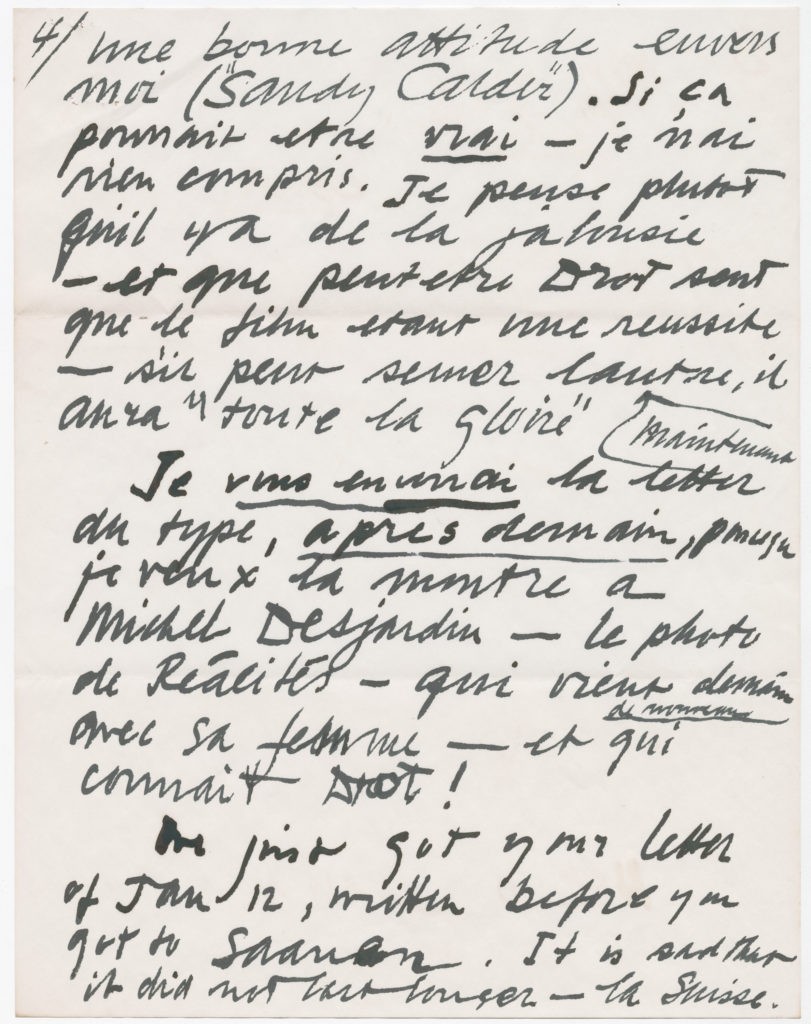

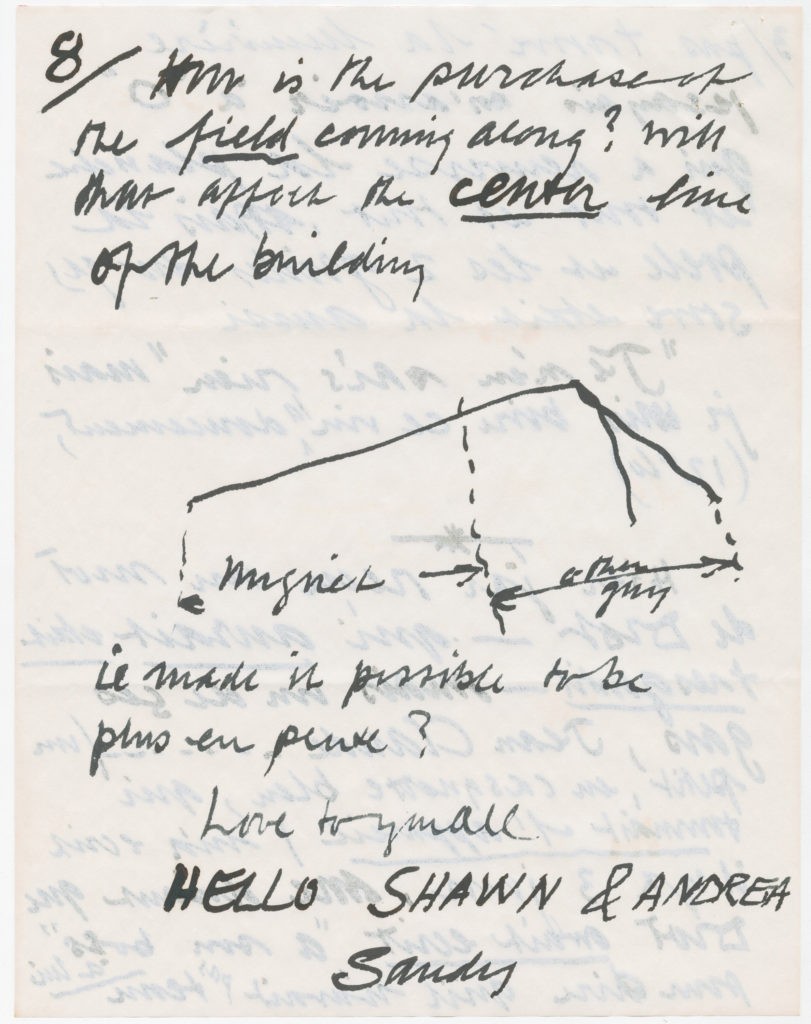

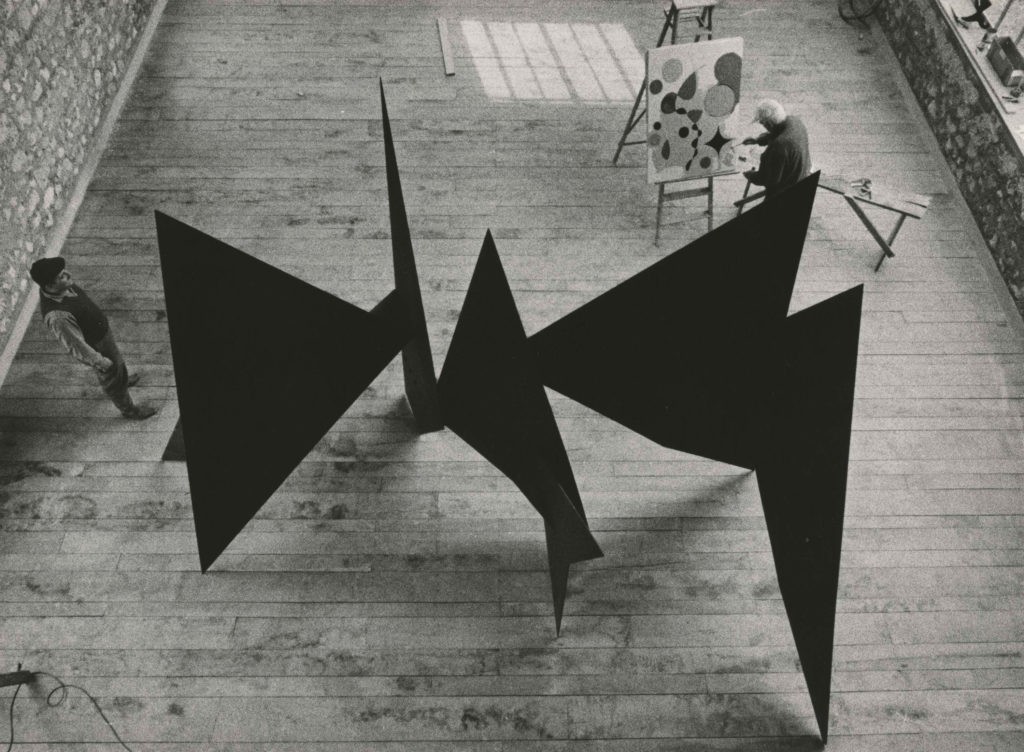

The big Saché studio had its origins in an emotion not normally associated with Calder: envy. He had visited the painter Pierre Tal-Coat’s studio in Normandy—an old priory with a newer “very large and high” barn: “The size of the studio gnawed at me the moment I saw it, and I became very jealous.”[4] He wrote Jean in Saché to get going on a big new studio ASAP. It would occupy a hillside Calder had encountered while accompanying Jean on a rabbit hunt. The site was prepared: The hill was hollowed out and the excavated fill bulldozed into a promontory. The project required the agglomeration of fourteen separate parcels of land. One in particular preoccupied Calder, as its inclusion would improve the feasible slope of the promontory: “Is possible to be plus en pente,” he asked Jean in his typical correspondent’s franglais.[5]

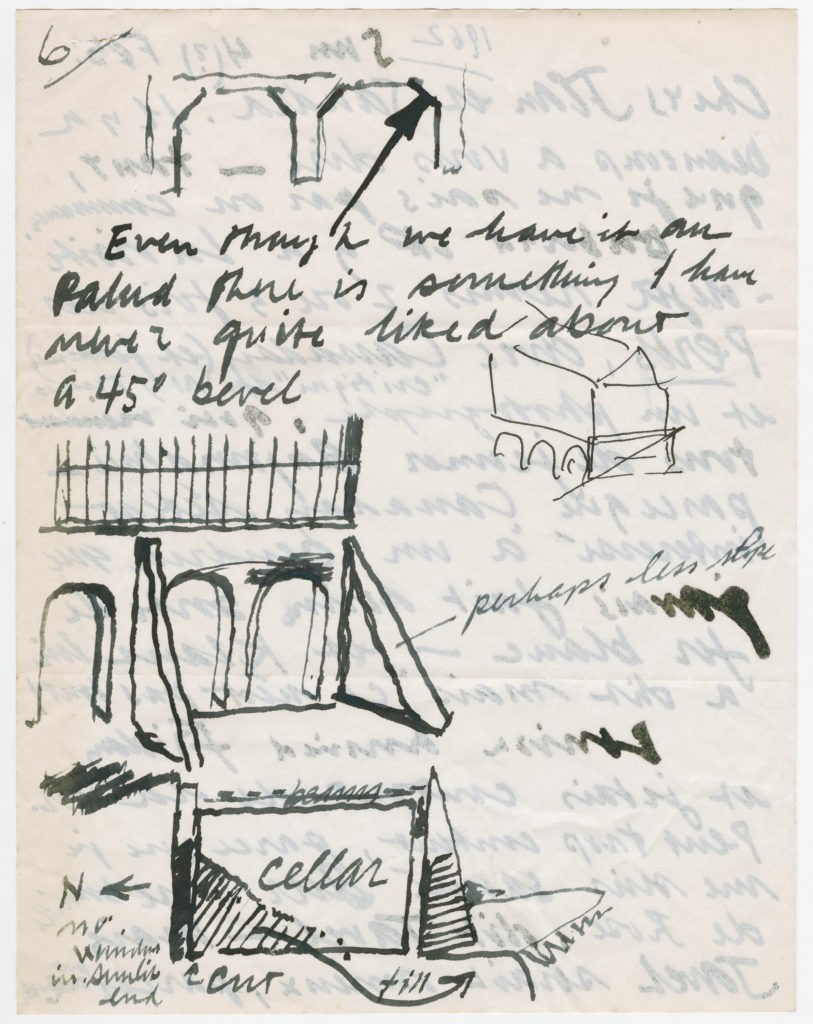

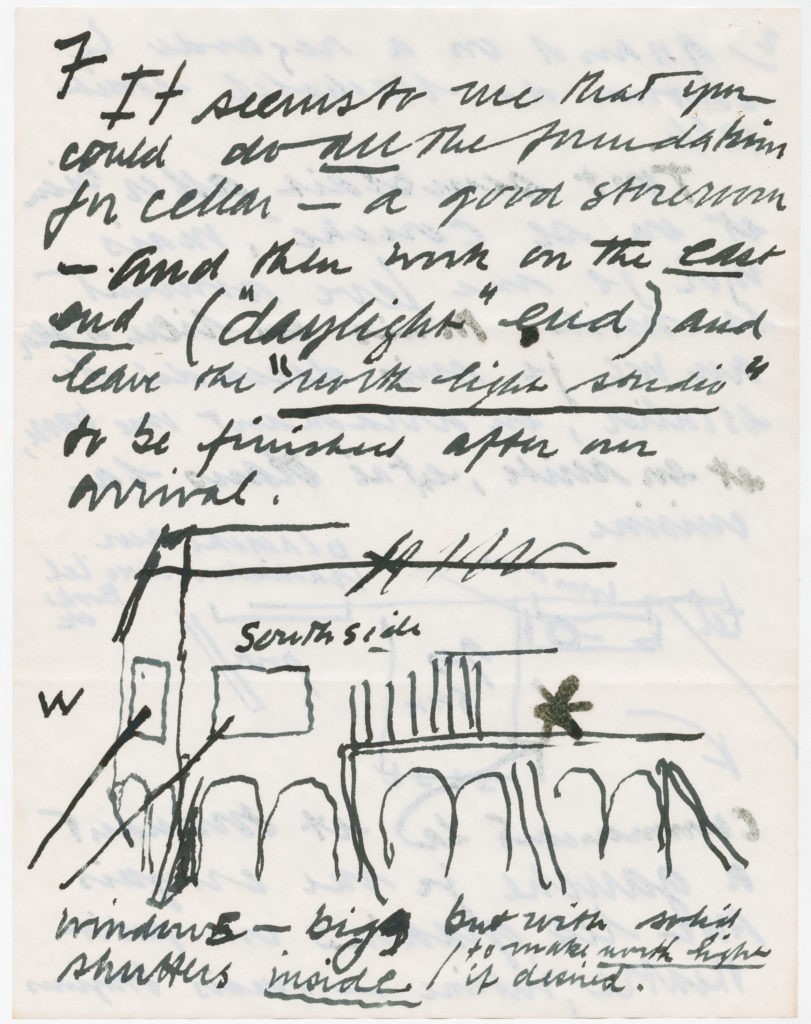

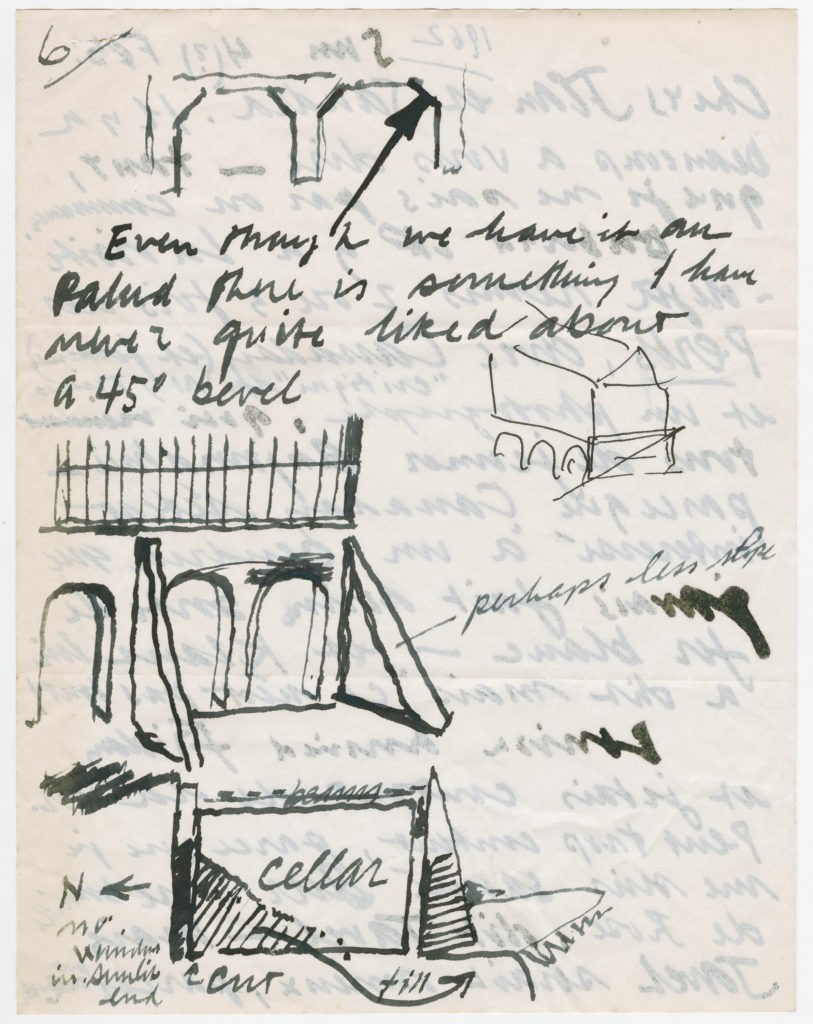

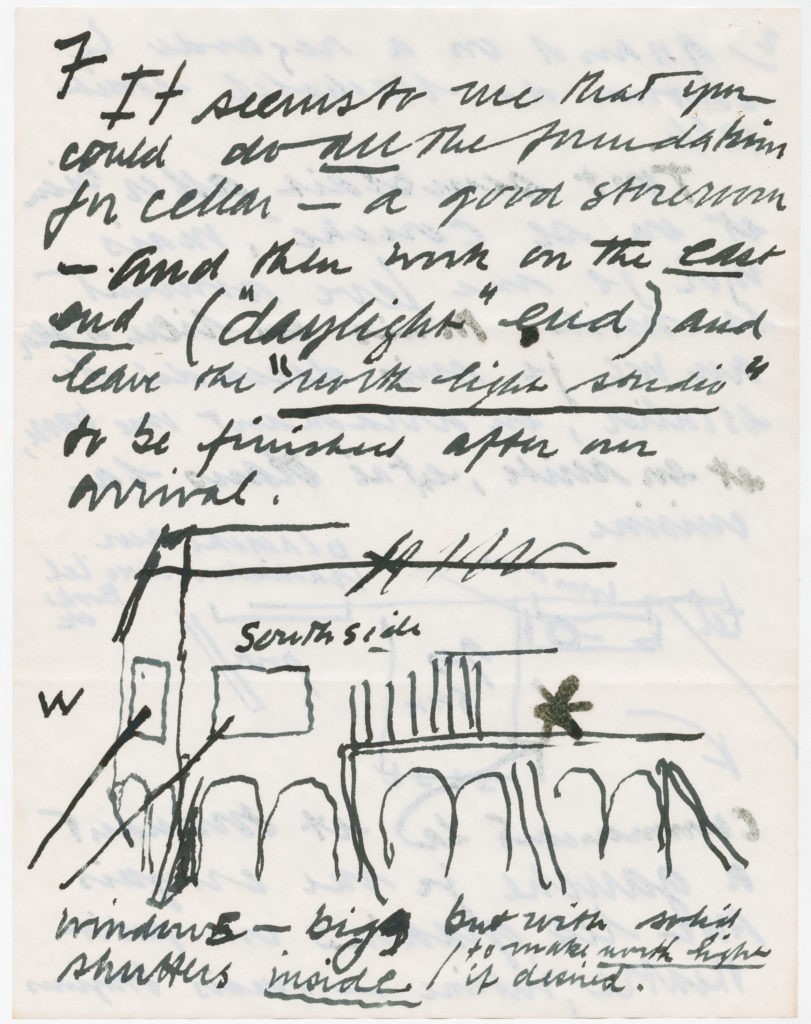

Lovely illustrated letters from Calder to Jean survive in the archives of the Calder Foundation. These, in Calder’s words, describe “what it would be nice to achieve.”[6] The intimacy of the two obviated the need for anything resembling construction drawings. Even so, the lo-fi manner in which Calder mused and Jean executed is hard to imagine happening today, in the highly regulated Europe of the twenty-first century, even in the village of Balzac. At one point Calder’s daughter Sandra, by then married to Jean, wrote to get clarification on the number of arches on the ground floor and submitted two different drawings with instructions for “Pop” to circle one. Another one from Calder: “I will think more about the dimensions while you are flitting about.” Presumably this means Jean’s haggling with the fourteen local landowners in a peasant opera, which must have resembled a scene from Marcel Pagnol’s Manon des Sources. Something in the way of “a bigger drawing” was eventually submitted to the local authorities, but by then the construction was well under way. Better to apologize than ask permission, as the saying goes.

The building took eighteen months to complete, and its finished form deviates in only minor ways from Calder’s expressed wishes. At some point the separation between the north-lit painting area and the studio, which Calder had originally envisioned as some kind of wall with large doors but “not a cloison,” was dropped. I imagine he decided that the demarcation of the two spaces by what he called the “up” of the windows (meaning the extra height of the glass in the painting area) was enough. Overall, Calder’s preoccupations as architect of what he referred to as “my new shop” were straightforward and consistent with what interested him in his previous artmaking spaces: site, light, and ventilation. He created a well-tempered environment, anchored in the local vernacular but tweaked à la Calder. As his work became more monumental, his space requirements increased. Indeed, his most imposing works were fabricated off-site, in a foundry in Tours. Saché was engineered as a space not so much for making art as for considering it. It was never itself a monument, even if aspects of it seem monumental in scale. Like Calder’s art, it is the size it wants to be.

If Calder had been an architect, he might have been part of what Bruno Reichlin has called “poetic functionalism.” This would put him with his friends Jean Prouvé, Oscar Nitzchke, and Paul Nelson. (They are sometimes referred to as the School of Paris as a way of distinguishing them from Le Corbusier, who presided over the other principal line of thinking in twentieth-century French architecture.) Like theirs, Calder’s buildings have no a priori “style” as Corbusier’s aestheticized machines for living do. Rather, they invent programmatic solutions to architecture which, if they are the most effective, are also instrinsically attractive. Like Prouvé, who hated to be told his work was beau (beautiful) and much preferred to pronounce it bien (good), Calder dealt imaginatively with the tasks and materials at hand. With his grilled steak à la chaise in mind, perhaps we should consider him a “ludic functionalist” with a flair for recycling. The cobblestones of the studio promontory overlooking the Indre valley were obtained by Calder from the city authorities of Tours who, he had heard, recently decided to blacktop its streets. He laid them out in a pattern that appears to have been there forever, predating the building itself. The only giveaway is the signature “AC” in the stonework.

In constructing Saché, Calder worked primarily within local architectural norms, and his signature moves do not stick out. The ossature of the roof is lighter and freer than the traditional construction usually seen in the region, but the form and volume of the roof are local. Calder provided for the building’s structural needs with lumber rather than hewn beams, but he effectively replicated the latter by twinning planks and then reinforcing them, using his intuitive engineer’s knowledge—plus the experience he had gained putting ribs and gussets on his monumental sculptures. The ground floor has simple Romanesque arches. Perhaps they represent Calder’s traveler’s idea of old France, a personal preference rather than a reference. Louis Kahn would have approved. They also evoke the nineteenth-century American industrial buildings that young Calder, like Kahn, would have seen in Philadephia, as much as they do the prevailing architectural style of the turn of the first millenium.

Saché is a long way from Roxbury. The evolution of Calder’s art over a quarter century can be understood in the respective architectures and constructive histories of the two studios. Roxbury was acquired, in the grand American tradition, with 100 percent leverage. The down payment was provided by an old friend from college. On top of that, Calder gleefully borrowed against his whole life insurance policy and took care of the balance by taking out a mortgage. It was the first place Calder owned. In addition to building on the preexisting foundation of the ruined barn, he conserved its stone silo. The barn’s understated and lovely functionality recalls Robert Motherwell’s studio in Amagansett—designed by another poetic functionalist, Pierre Chareau—which consisted of a World War II surplus Quonset hut and a greenhouse. For Calder, the materials at hand were a barn ruin, cinder blocks, and prefabricated greenhouse windows. Here he first rigged up his famous system of screw eyes in the rafters (“My sky is studded with … screw eyes”[7]) so he could hoist and suspend mobiles using a purpose-built pole with a hooking apparatus rigged on its end.

Roxbury was built at the tail end of the Depression and the eve of war. Whatever magpie habits Calder had already developed as an artist were reinforced by the material penury that prevailed. He recalls cutting up his aluminum boat (itself a homemade object for puttering around the pond) around 1942 to use the scrap metal in artworks (and around the house). Later in life, when his cash flow improved, he bought a contiguous parcel of land in Roxbury rather than upgrading or expanding the existing studio. He needed a change of venue in order to revise his work space.

Calder logged much more seat time in Roxbury than in any other studio in his lifetime. It shows. Today the studio looks as if its occupant of nearly four decades went out for a pack of cigarettes sometime in the 1970s and never came back. Unopened paint tubes whose manufacture was discontinued fifty years ago sit in their original mailers from Paris. The only overt evidence of subsequent human intervention is a table with orphaned bits and pieces of Calder works that the Calder Foundation has been trying to identify over the years—forensics at a crime scene. Kenneth Frampton once described Chareau’s elaborate interiors as technosurrealist. With a nod to Frampton, I would call Calder a gizmo-surrealist. For example, the wooden worktable with the old radiator hanging off it to stabilize its surface is coming at the question “What is art?” from a different direction than Rauschenberg. While Rauschenberg’s Combines had objects culled from junk piles that appeared to be falling into the room from the art on the wall, Calder used those same sorts of objects to make functional furniture while taking the same spatial liberties.

The bulk of the Roxbury studio space today consists of careful piles and accretions of various materials and found objects: glass, wire, ebony, aluminum. At first one is enchanted by its seeming nonchalance, but its clarity of purpose reveals itself soon enough: Every last bit of this stuff was on its way to becoming a Calder! It reminds me more of a rural tinkerer’s shop—someplace you take your Bugatti carburetor to be rejetted—than an artist’s studio. As the value of Calder’s art continues to skyrocket, and the conversations about art are overwhelmed by talk of money, it is useful to spend even a few minutes in this modest little “shop.” Few ateliers of departed artists are in such a state of preservation, and among those none evince such powerful connections between place, existence, and art.

The distinction between found and created spaces is a useful one here. Roxbury is primarily a found space, within which Calder created his own spaces of habitation and production. The house was already there, and until 1938 part of it served as his studio. When he built the studio, he used what was there (the foundation and silo) or readymade (cinder blocks and windows). The program was likewise simple: an easy walk to the house, light for making, a fireplace for warmth.

Saché, on the other hand, is created. The landscape is changed. Earth is moved. A promontory is made from part of a hill. Trees are planted. The stonemasonry is a big step up from cinder blocks, and the roof structure is seriously custom. Whereas Roxbury nestles comfortably in an existing landscape, the Saché studio dominates the area. After the studio there was completed, Calder would build a house from scratch. He strikes me as someone who liked to be able to pop home for lunch or even just a cup of tea. There are no bathrooms or kitchens in his studios.

By the time Calder built Saché, his financial situation had improved considerably. He was almost cavalier about the budget in correspondence with Jean, telling him to get some money from his Paris dealer, or else he could send a check from a Credit Suisse account. Not that he was being extravagant. Neither the studio nor the house are by any means bourgeois. But I imagine it was complicated enough patching together the needed parcels without asking for owner financing or working out a mortgage with some bank in Tours. At this stage in his life, Calder could pay cash on the barrelhead and get on with more important things.

By this time, Calder was focused primarily on monumental works executed by a foundry in Tours. There is a “north light” space for painting, but it was not often used. So the studio became a place to display and contemplate the works as they emerged from the foundry. The conception of the building and the site reflects this. One can spend hours in the studio itself studying the works from various angles and directions as the light evolves throughout the day. Works could also be sited on the cobblestone promontory below the studio and looked at from above, with the valley as backdrop, or walked around as if in an urban context, with the studio itself behind. Another site, behind and above the studio, in a clearing before the woods, provided a natural backdrop for large works. I imagine that from the panoptic vantage point of the studio Calder could study the reactions visitors had to exterior works as they approached.

Saché is today called Atelier Calder and has hosted artists-in-residence for the past twenty-five years. During my visit, the studio was occupied by maquettes made by Monika Sosnowska, with whom I briefly crossed paths at the house. Like the artists who have preceded her, she has the privilege of living in Calder’s personal space, among his gizmos, and of making art in his studio. François Premier and the other family residences, including the original Moulin Vert with which Jean started the whole stampede, have long since passed into other hands. This adaptive reuse of the Saché studio is sufficient, however, to allow the spirit of Calder to keep watch on its habitat.

With all his architect friends, why did Calder never avail himself of their services? When he built Roxbury, he used an old Stevens Institute classmate of no particular renown to draw the plans—a ministerial task required by the local authorities. When he built his mother’s house, Oscar Nitzchke signed the plans but had no involvement. Josep Lluís Sert, with whom Calder collaborated on one of the high points of his career—the Mercury Fountain at the Spanish pavilion at the 1937 Paris International Exposition—wanted to do the house at Saché. It’s easy to imagine that Sert wasn’t the only one to volunteer his services, but clearly Calder was having fun on his own. The results are pure Calder architecture. At first glance, the Saché structure looks like a slightly suburbanized Norman farmhouse with a bolted-on greenhouse perpendicular to one end. On closer inspection, however, it becomes clear that the joining of the two is as faceted and idiosyncratic as a Calder sculpture. The western end of the house is rectilinear, but the eastern greenhouse end is oriented along a diagonal. Externally, the corner turns almost abruptly; all the craft is up close and inside. How one turns a corner is one of the basic, and one of the most challenging, tasks an architect faces. Calder got it. In addition, he left his stamp on the two roofs—one of shingles, one of aluminum—and the main house’s roof, which is angled at its bottom so as to create a long, very Calderesque triangle of shingles. Into the greenhouse’s interior juts the hewn structural beam of the house, a grace note of handmade architecture that also connects the house to Roxbury, since the prefabricated glass and metal panels of the greenhouse are similar to ones Calder used in Connecticut. Here we are in the realm of bricolage rather than Le Corbusier’s “Poem of the Right Angle.” Inside, the long, narrow space to the rear of the first floor is neither a room nor a hallway. Today, nearly empty, it is programmatically puzzling. But period photos of it chockablock with Calders pinpoint its use. Calder liked to live with what he made—and this was not limited to the gizmos for daily life, like the light fixtures and kitchen utensils. He was a man who also liked to keep his art close to home.

One architect friend of his described the Saché house, with evident frustration, as a pastiche—an insult in art-critic-speak, but in this case hard to argue with as a literal description. To this I say: But, ah, what a pastiche. In my view, Calder was merely trying to demonstrate that there is no such thing as “architecture” per se. He wasn’t trying to sculpt a space of habitation that made some sort of statement. Instead, he took a look around and tried to add a little to what was already there, playing with it, rearranging some bits, identifying its essence in the process through small gestures. If one looks at the slowly fossilizing footprint of Calder in Saché, one could go so far as to say that this man mustered a plausible response to one of the toughest enduring questions of modernism: How can modernism coexist with the world that preceded it? Too much modernism dictates to the Old World, imposes itself inappropriately on the preexisting landscape (or, worse yet, scrapes it clean), and sucks up all the oxygen when it moves in. (This is the subject of many exhibits at the 2014 Venice Architecture Biennale, in particular the French pavilion, “Absorbing Modernity 1914–2014: Promise or Menace?”) Much modernism ignores, or even disrespects, its hosts. Not so Calder’s Saché project. The sculpture he offered the commune sits comfortably on the town square in its envelope of traditional buildings. Trees and vegetation have grown up around Le Carroi, integrating it further over time into the landscape of the Touraine, as Calder intended. His Romanesque studio looks more timeless with time. With the Atelier Calder program of artists-in-residence, real life remains present.

Calder is present in Saché on many other levels. He donated artwork to the local town fair to raise money to build the school, and he helped underwrite the construction of the local bus station. At a recent exhibition in Tours, “Alexandre Calder en Touraine,” dozens of objects and works which Calder sold for charity or gave as gifts to his many local friends came together as loans to the show, mapping in great detail his quotidian interactions with his fellow villagers over decades. If architecture is about organizing the spaces of habitation, production, and public life in ways that make the world a better place (we can argue about the metrics of that later), then Calder made great architecture. But he would never see it that way. He would be too busy cooking steak à la chaise.

Hauser & Wirth, Los Angeles. Calder: Nonspace. Exhibition catalogue. 2019.

Andrew Berardini, The Cosmic Mathematics of Alexander Calder

Solo Exhibition Catalogue“Calder in France.” Cahiers d’Art, no. 1 (2015). Edited by Alexander S. C. Rower.

Susan Braeuer Dam, Calder in France

Robert Melvin Rubin, An Architecture of Making: Saché and Roxbury

Agnès Varda in conversation with Joan Simon

Magazine, MonographAlmine Rech Gallery, New York. Calder and Picasso. Exhibition catalogue. 2016.

Robert Slifkin, The Mobile Line

Susan Braeuer Dam, Liberating Lines

Jordana Mendelson, Picasso, Miró, and Calder at the 1937 Spanish Pavilion in Paris

Group Exhibition CatalogueMuseo Jumex, Mexico City. Calder: Discipline of the Dance. Exhibition catalogue. 2015.

Alexander S. C. Rower, Calder: Discipline of the Dance

Solo Exhibition Catalogue