Photographs of sculpture are as old as photography itself. When a great photographer confronts a great work of three-dimensional art the results can be thrillingly alive, with sculptural form animated by all the lights and shades and mercurial energies of life as it is experienced moment by moment. Some of the very earliest daguerreotypes feature arrangements of sculptural fragments. And William Henry Fox Talbot’s The Pencil of Nature, by many reckonings the first photographically illustrated book, contains two studies of a classical Bust of Patroclus. In the text for The Pencil of Nature, Fox Talbot celebrates the variety that photographers can achieve, observing “how very great a number of different effects may be obtained from a single specimen of sculpture.” He writes of turning the sculpture “round on its pedestal,” of making different choices “of the direction in which the sun’s rays shall fall,” and he comments on the superior effects he believes can be achieved “by delineating them in cloudy weather [rather] than in sunshine.”[1]

A sculpture is designed to dramatically occupy our world. Fox Talbot was among the first in a long line of photographers who have been inspired by the sculptor’s exhilarating encounters with form and space. The documentation of the architectural and artistic achievements of the past, a central preoccupation of photographers in the first decades of the medium, fueled a gathering romance with sculptural representations of Ancient Egyptian rulers, Hellenistic gods, Romanesque Madonnas, and Gothic saints. When Edward Steichen, in 1902, photographed Auguste Rodin contemplating The Thinker, the statue came to life and the sculptor became a statue, a meeting of creator and creation in the opulently romantic chiaroscuro of Steichen’s gum bichromate print. Eugène Atget, around the same time, lingered on the decorative statuary in the gardens and parks of Paris and Versailles, regarding stone monuments as woodland spirits. Constantin Brancusi photographed his Bird in Space as if it were bursting into life. There is something of the spirit of Pygmalion about photographers who turn their attention to sculpture. They highlight potentialities; they release the dynamism latent in wood, stone, and metal.

Herbert Matter’s photographs of the art of Alexander Calder comprise one of the great and as yet too little understood and celebrated chapters in this formidable history. In the late 1930s and 1940s, Matter responded instinctively to Calder’s audacious forms and resolute emotions. For Matter, the confrontation with Calder’s work provoked precisely the animation of the inanimate that had fascinated photographers since Fox Talbot’s day. Only now the process was pushed several steps further, because Calder’s sculpture often actually moved, offering a kinetic dimension to which the photographer could respond with the quickening action of the camera eye.

We do not know exactly how Matter and Calder met, but it was certainly soon after Matter came to the United States in 1936, and it is possible that they had already crossed paths in Paris in the early 1930s. By the mid-1930s, Calder was recognized as a leader in the experiments with pure abstract form that were electrifying the transatlantic avant-garde, and Matter felt the pull of those discoveries. Although Matter, who was born in Switzerland in 1907, was nine years younger than Calder, they counted some of the same Parisians as friends and acquaintances. It could be that Fernand Léger had something to do with their getting to know each other. Léger had been a good friend of Calder’s since the early 1930s. And he would quite naturally have wanted Calder to meet Matter, whom he had first known as a student. Calder and Matter might have also met through the curator and critic James Johnson Sweeney, who was friends with all three men and travelled in the same transatlantic circles. Whatever the initial connection, Calder and his wife, Louisa, always felt at home with an international cast of characters, and Matter became one of a considerable number of European émigrés who received their warm welcome in the United States.

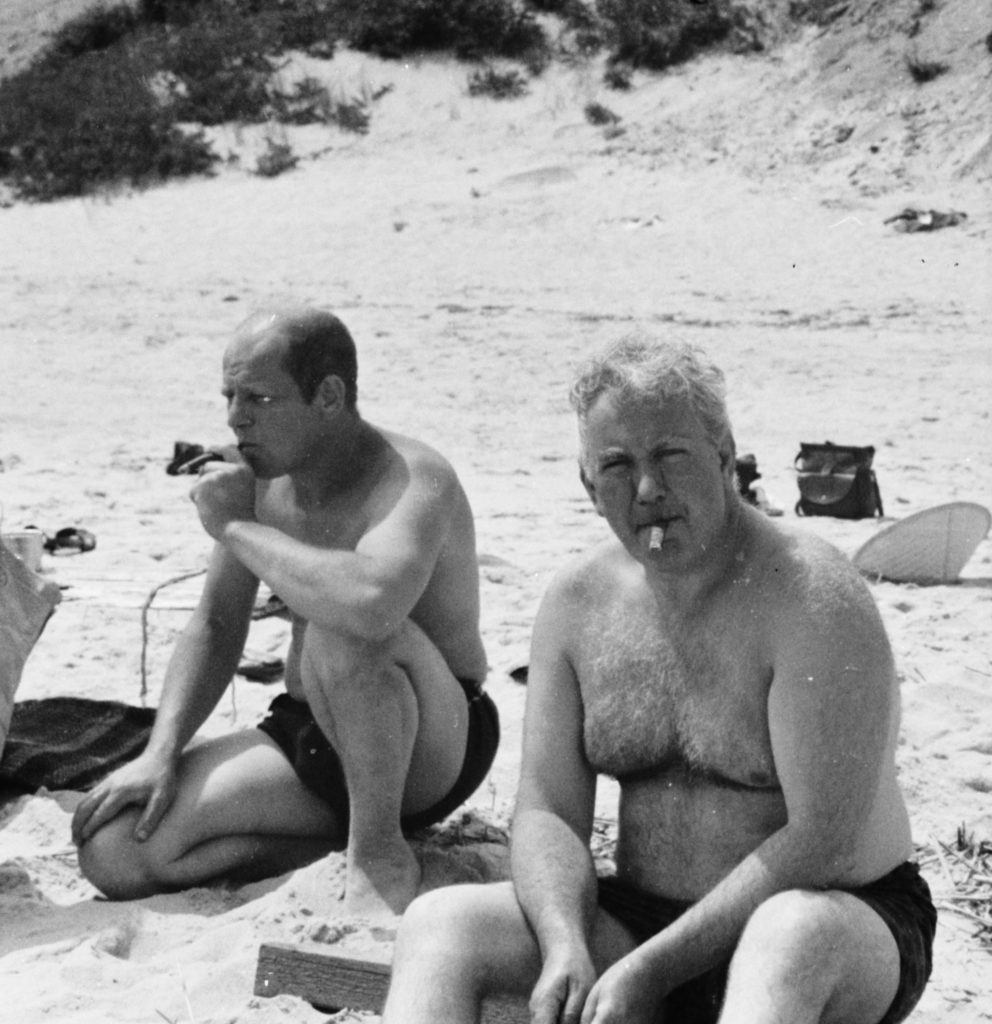

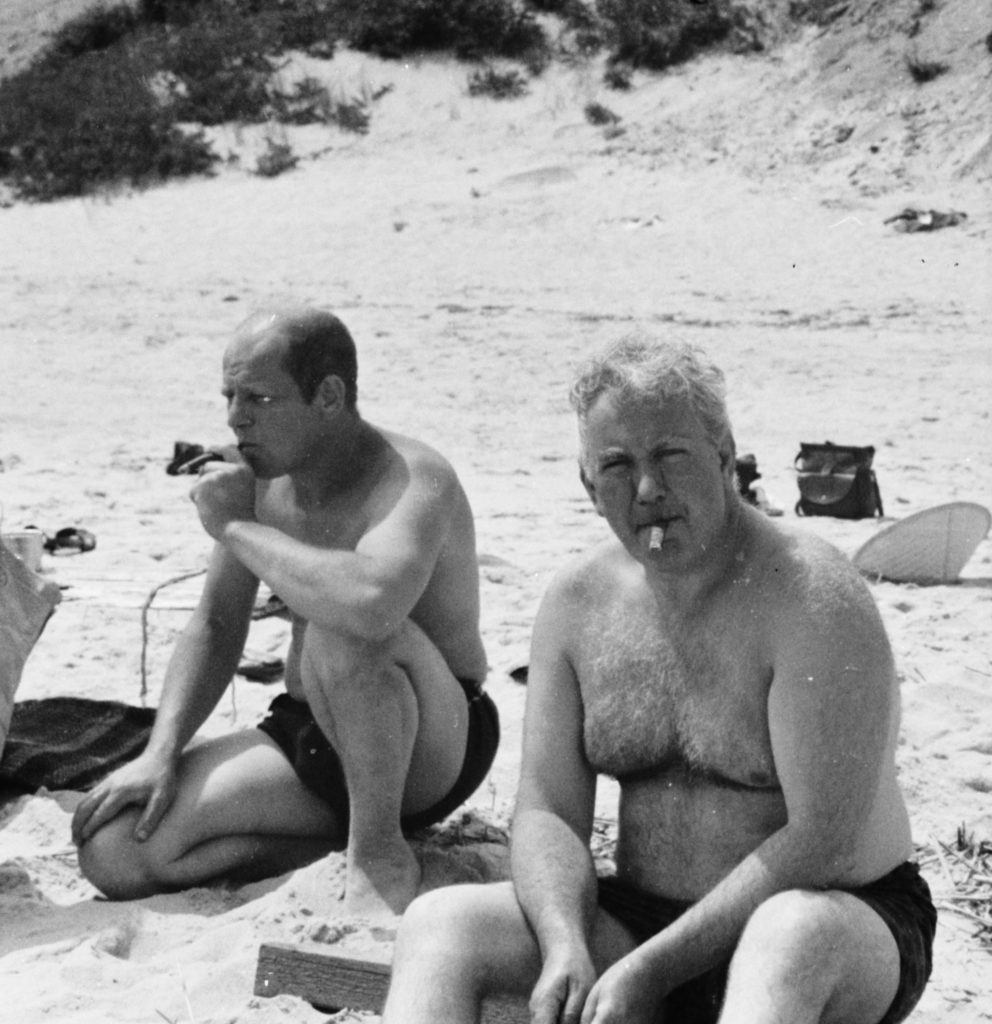

Matter had already built a major reputation for himself in Zurich designing posters, many for the Swiss tourist industry, that combined bold, modernist typography with striking photomontage elements. In New York, he was immediately embraced by the most progressive figures in graphic design. He worked with Alexey Brodovitch, the art director at Harper’s Bazaar, and also for Vogue. In 1939, when the New York World’s Fair was going up, he played a large role in the design of the Swiss Pavilion. Matter was a rather glamorous figure, tall and lean and handsome. A couple of years after he arrived in New York he met a gifted and beautiful painter by the name of Mercedes Carles, who was a student and close friend of Hans Hofmann. They were married in 1941, by which time Herbert was as much a part of New York’s downtown artistic world as of the city’s uptown magazine and advertising circles. The Matters were close to Jackson Pollock and his wife, Lee Krasner, and although Calder and Pollock were probably not much more than acquaintances, Matter’s photographs of them together on a Long Island beach document a fascinating encounter between two American revolutionaries.

That the Matters and the Calders became good friends was not surprising. The Calders, an extraordinarily stable married couple, liked to connect with other interesting married couples, and nobody can minimize the appeal of Herbert and Mercedes Matter, this youthful, elegant, gifted duo. With the arrival, in 1942, of Herbert and Mercedes’s son, Alexander, they would also all share the experience of bringing up children. Like Calder, whose father had been one of the best-known sculptors in the United States in the 1920s, Mercedes came from a prominent artistic family; her father, Arthur B. Carles, was a pioneering American abstract painter, and her mother had modeled for some important photographs by Steichen. Calder, whose artistic impulses were grounded in an engineer’s close attention to the mechanics of nature, had little patience with unabashed aesthetes and would have found Herbert’s technical competence and ingenuity enormously appealing. Calder bonded with this photographer and graphic designer whose focus on the nuts and bolts of the creative process—whose know-how in the darkroom and ease in handling typographical challenges—never stood in the way of his pursuit of lyric beauty.

Matter’s work with Calder began late in 1936 when he went to Calder’s storefront studio on the Upper East Side to photograph both the artist and his work in preparation for Calder’s third exhibition at the Pierre Matisse Gallery the following February. Matter also photographed the work when it was installed in the gallery. In 1940, when Calder had his fifth show with Pierre Matisse, Matter again visited the studio before the exhibition and worked at the gallery as well. Three years later, he acted as an advisor on the installation of Calder’s highly successful retrospective at the Museum of Modern Art, which was organized by Sweeney. By then, crisscrossing professional associations connected all these men, so that when Matter had a show of his own photographs at the Pierre Matisse Gallery, Sweeney wrote a brief text, saluting Matter as the rare “researcher … who is both artist and technician.”[2]

Over the years, Matter photographed Calder and his family in Roxbury, Connecticut, lingering on details in both the studio and the house. They worked together on a couple of films: the 1944 Alexander Calder: Sculpture and Constructions, made on the occasion of the Museum of Modern Art retrospective, as well as Works of Calder (1950), which premiered at the Museum of Modern Art in 1951. In 1957, there was talk about Harry Abrams publishing a book of Matter’s Calder photographs, with Calder assiduously promoting the project. Even at the beginning of the 1960s, nearly a quarter of a century after they first met, Calder was reaching out to Matter: there were discussions about a film of the Cirque Calder (1926–31); Calder asked Matter to photograph a show at the Perls Galleries, urging him to leave out the plants that were part of the gallery decor; and Calder was in touch with UNESCO, hoping to persuade the organization to publish photographs Matter had made in the 1940s in Brazil, a country where Calder and Louisa had enjoyed themselves enormously and felt warm ties.[3]

In the late 1930s, when the Swiss émigré was initially photographing the American’s work, Calder’s genius was still youthful and a little roughhewn, a greatness fueled by zigzagging imaginative forays and a wild experimentalism, a let’s-try-it spirit. By the time Matter was back in the studio in 1940, Calder had found his way to the seamless classical authority that characterizes landmark works such as Eucalyptus (1940) and Black Beast (1940). But no matter how magnificently homogeneous Calder’s visual rhetoric would sometimes become in the 1940s and 1950s, he never abandoned his radically heterogeneous approach. Calder always enjoyed mixing things up. If he was going to be a sort of purist, he was going to be a complicated and idiosyncratic purist, with his bold and sensuous forms forever grounded in the comic instincts that had first flourished in the Cirque Calder and the wire figures and portraits of the late 1920s. Calder regarded his plunging, careening forms with a lovingly human eye. He emphasized the sleek or awkward movements in a mobile in much the way he had earlier emphasized the quality of movement in a wire sculpture of an athlete or a dancer. He gave even abstract forms a caricatural edge.

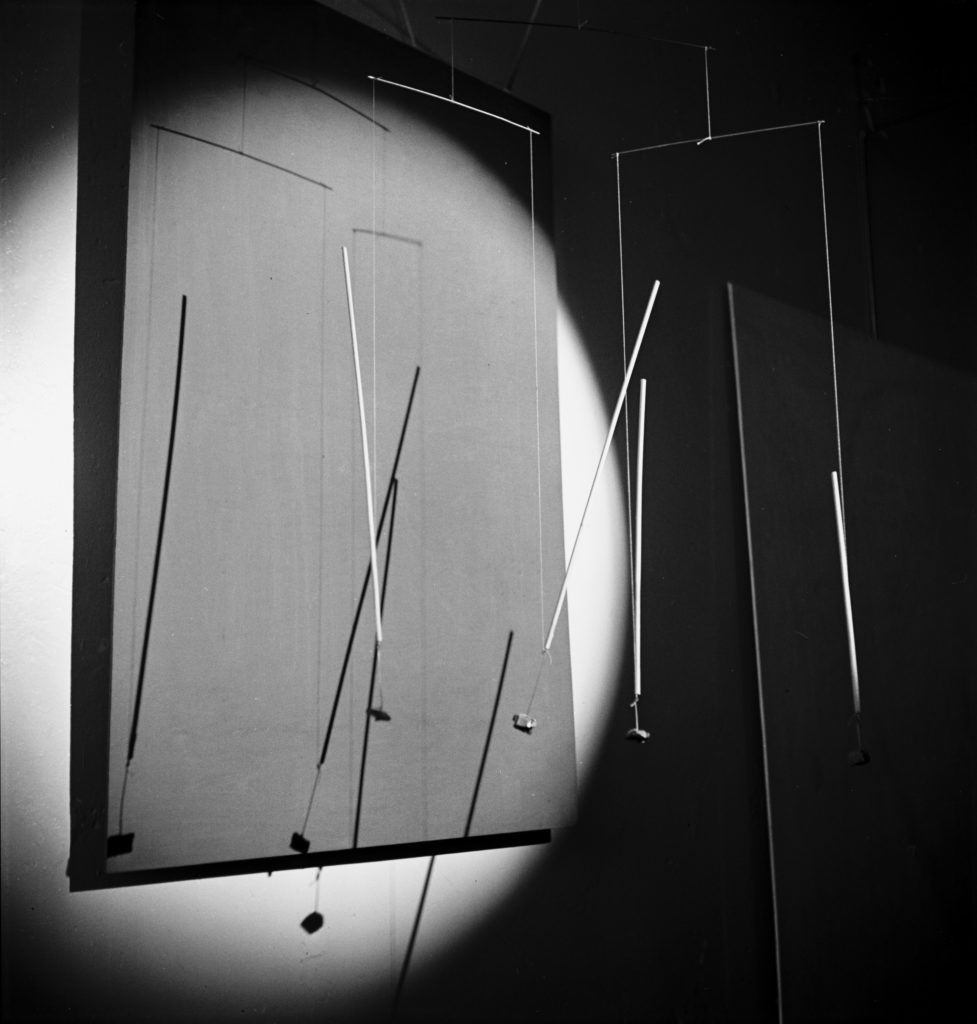

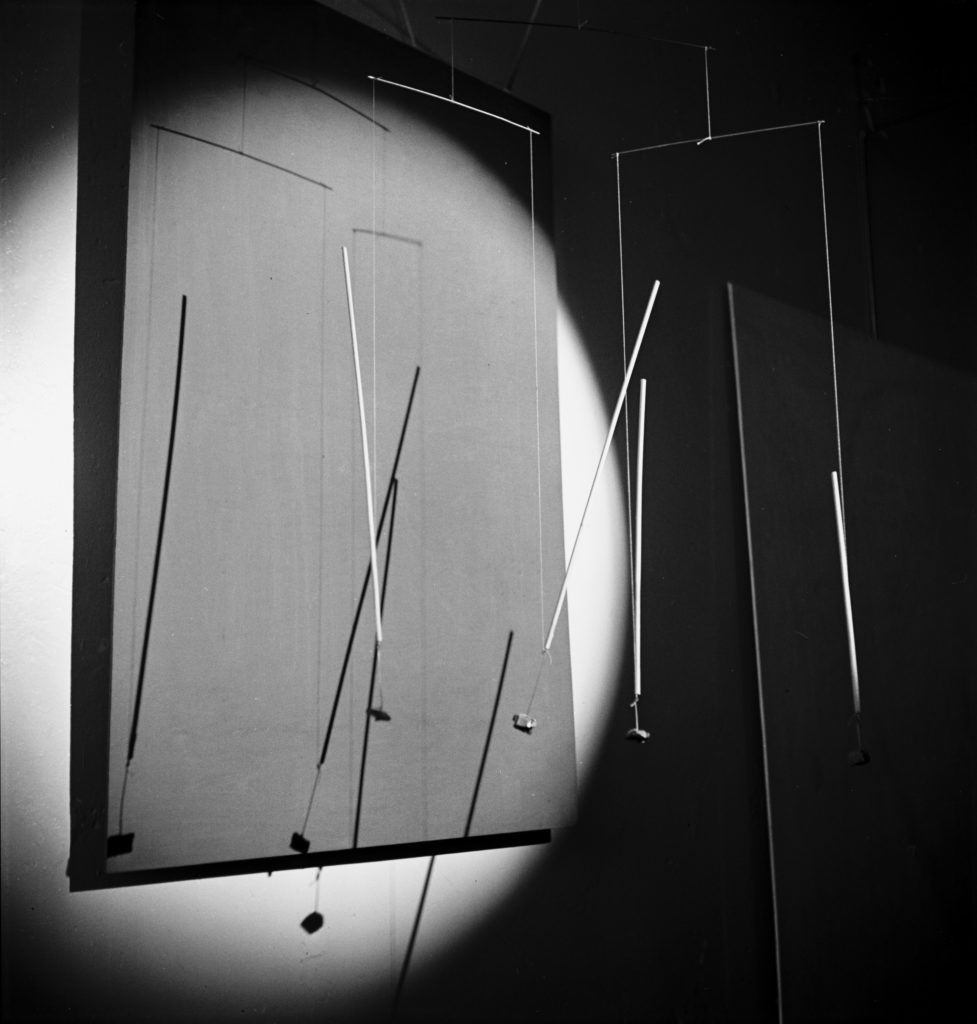

Matter always responded immediately to what Calder was doing. Sweeney would later observe, when Matter exhibited his own photographs at the Pierre Matisse Gallery, that “for him there are no technical taboos.”[4] And it was surely this rejection of all taboos, whether technical or artistic, that joined Matter with Calder in what might be described less as a collaboration than as a meeting of minds. They were certainly in sync in the first series of photographs that Matter made of Calder’s work in the storefront studio on the Upper East Side, a relatively narrow and deep space, painted white. Among Calder’s new works were arrangements of forms suspended before flat planes painted in red or white or yellow to create what were in essence mobile paintings, with the three-dimensional shapes casting shadows on the flat backdrops that defined the space. Matter had brought some photographer’s lights to Calder’s studio. And he picked up on the curved and angled shapes of wall-hung works such as Swizzle Sticks (1936) and White Panel (1936) as well as of freestanding works such as the imposing (and not yet quite finished) Devil Fish (1937). Matter created a dance of shadows along the walls that splendidly doubled or paralleled the shadow play in Calder’s work. Matter was attuned to all the quirks and particularities of the studio space. He allowed his camera to linger on old-fashioned woodwork and on buckets, cartons, bottles, and boxes. Matter’s photographs move between the formal and the informal, the planned and the accidental. There is an extraordinary feeling for the work of art as it comes into being, the fantastical freedom of forms emerging from the cramped old space.

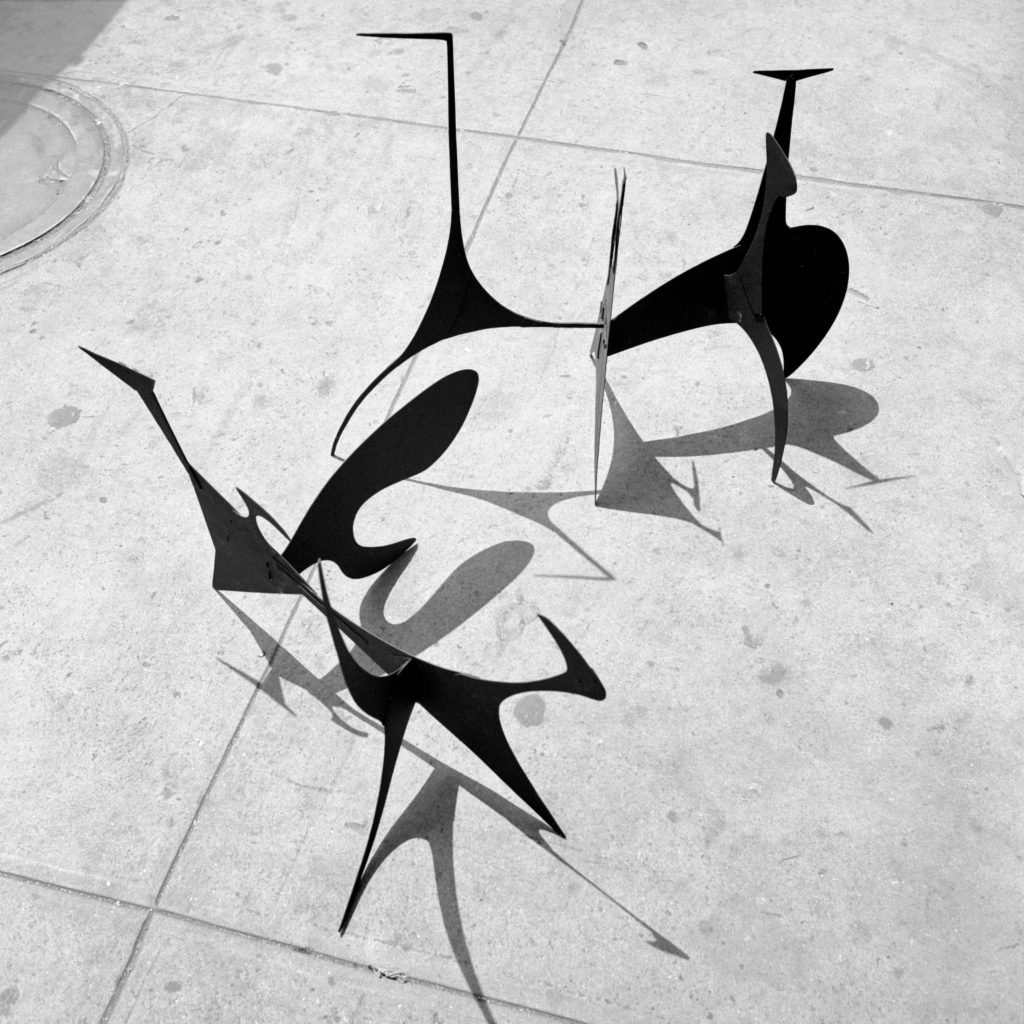

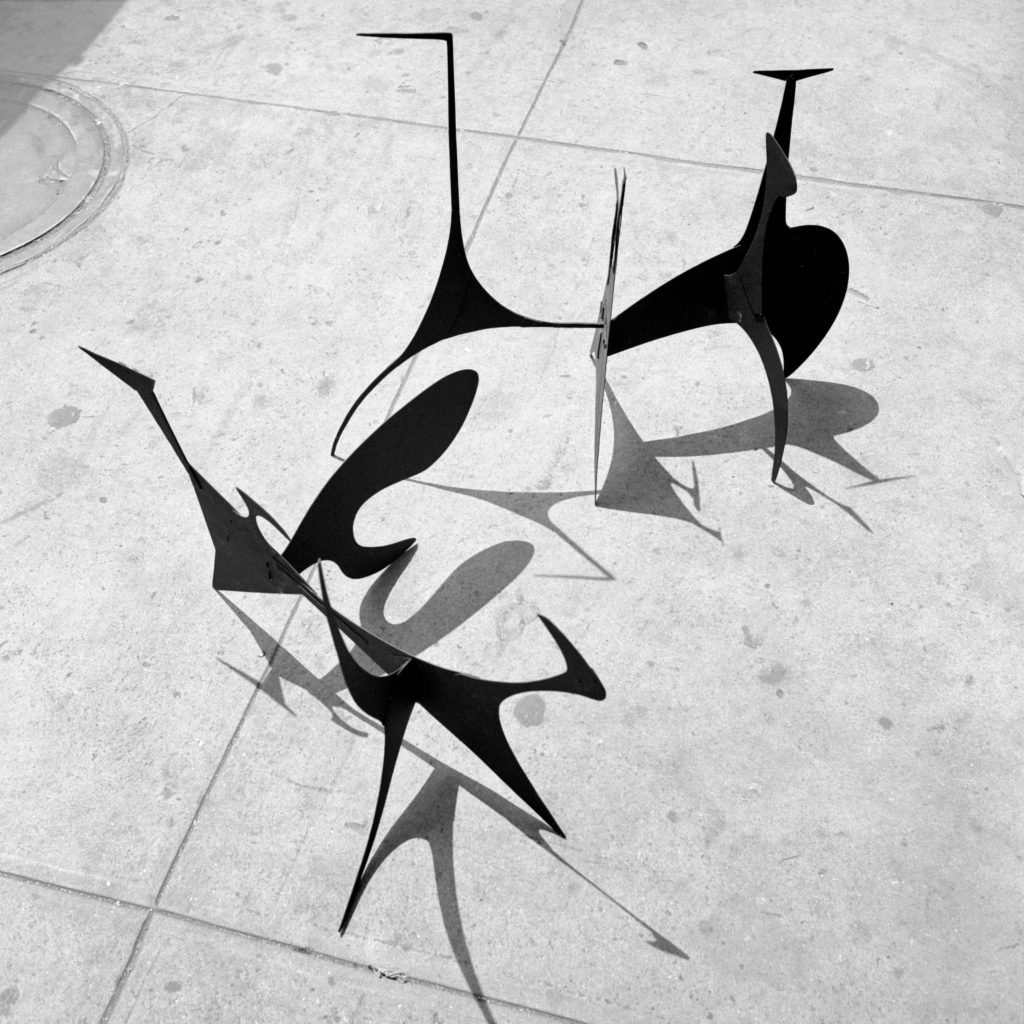

Calder and Matter were experimentalists with a taste for both the ideal and the ordinary, and the strength of Matter’s photographs rests in his willingness to allow Calder’s sculpture its multiplying metaphors. Matter refused to approach each photographic challenge in the same way. He resisted any temptation to overemphasize the element of austere astronomy in Calder’s work, with planets, suns, moons, and their interrelated force fields given a purist otherworldliness. What Matter understood instinctively was that whatever quality of Platonic idealism Calder’s forms sometimes suggested, his art was equally a matter of heartfelt improvisation, of immediate responsiveness. So even as Matter suggested the lofty formal power of Calder’s works, he emphasized how wonderfully they operated as experiences in a workaday world. At the Pierre Matisse Gallery, Matter photographed a wire sculpture of gymnasts set on a window ledge, so that their calligraphic contours were juxtaposed with a view of midtown buildings, the urban world that had first nourished Calder’s art. In a series of photographs done before the 1940 show at Pierre Matisse, eight stabiles and standing mobiles were taken out of the storefront studio onto the sidewalk, where they were photographed one by one and in a single instance as a duet of two stabiles. There is a sneaky wit about these photographs, a sense that the sculptures, having been born in the studio, are now taking their first steps out in the world. In those years when the crowds on the sidewalks of New York fascinated adventuresome photographers, Matter invented a new kind of street photography, with the street now the setting for the abstract work of art.

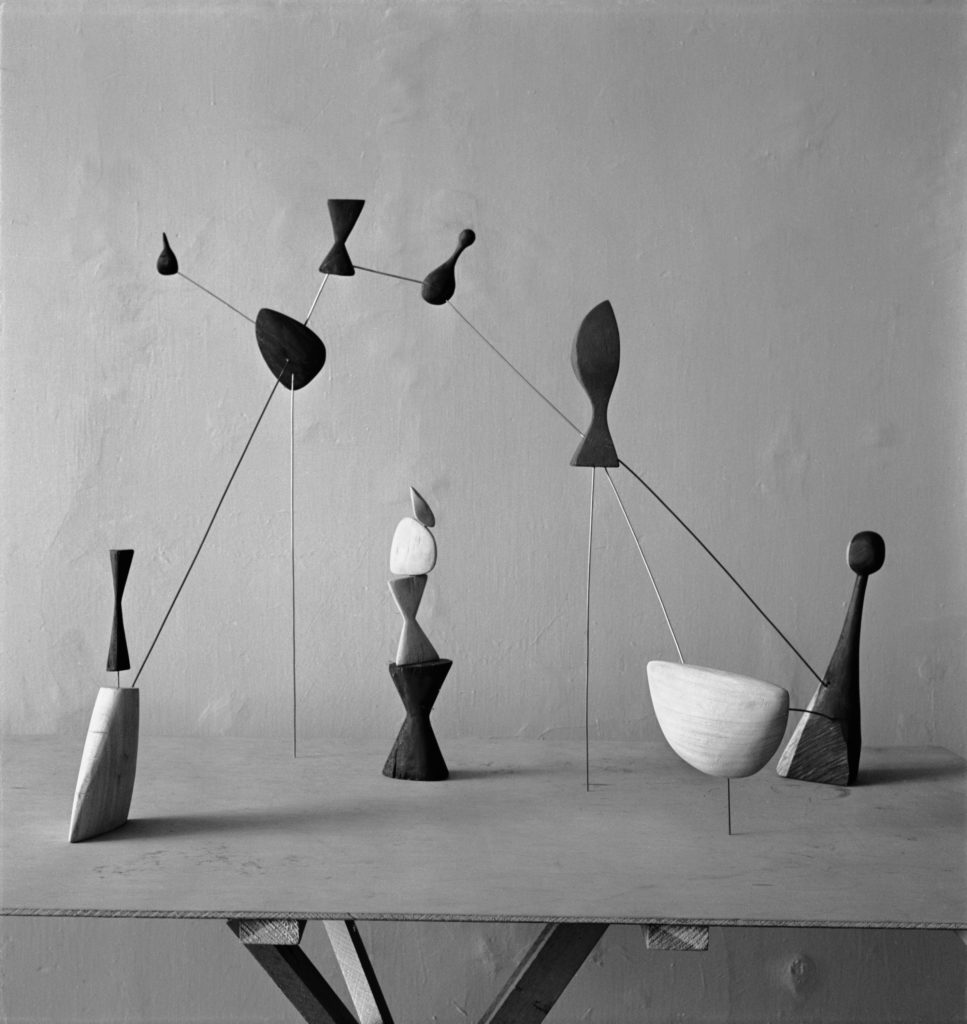

Calder’s art brought out the loosest, most easygoing instincts in Matter, who at other times could be a little over calculating as a technician, using high-speed or stroboscopic methods to achieve self-consciously stylish effects. There is something forced about certain passages in the second film Matter made of Calder’s work, where the overlapping images of mobiles and moving water, obviously meant to underscore the naturalness of Calder’s art, feel a little coy. But when Matter was in direct contact with Calder and his mobiles and stabiles, he was almost invariably loose-limbed, brilliantly casual. Visiting in Roxbury, at least sometimes with Mercedes and their son, Matter photographed the Calders eating out-of-doors, Louisa playing her accordion, and Sandy and Louisa and their two daughters in moments of impulsive tenderness. One can argue that these are basically family snapshots, only done by a master of the art, but they also underscore the close connection between the two men and help to explain why even Matter’s most formal shots of Calder’s work have a saving informality. Matter photographed not only the magician in his workshop, but also the details of the Roxbury house, all the delightful practical objects Calder produced: light fixtures, kitchen implements, a toilet paper holder. There is also a fine series of studies of the constellations, those works of the 1940s in which beautifully crafted wooden shapes are connected by wires to create dreamlike typologies. Whether in the relative formality of his studies of the constellations or in the unabashed informality of his studies of the Roxbury kitchen, Matter was invariably alert to the shadow play that deepened the richness of everything Calder did.

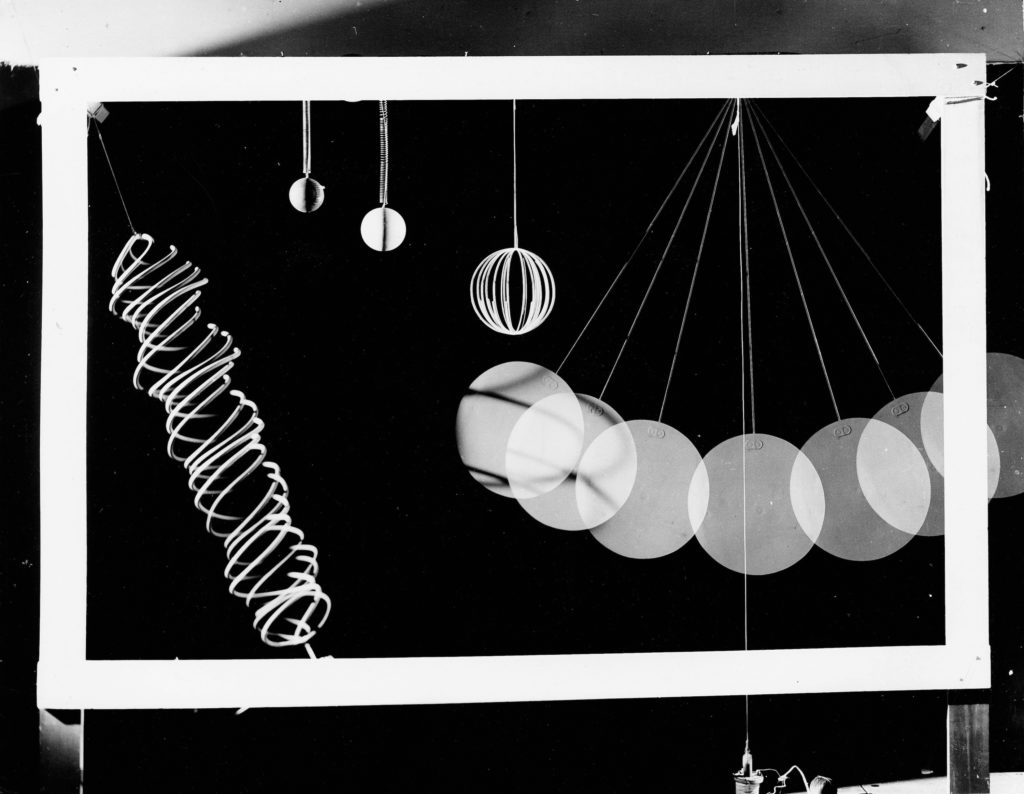

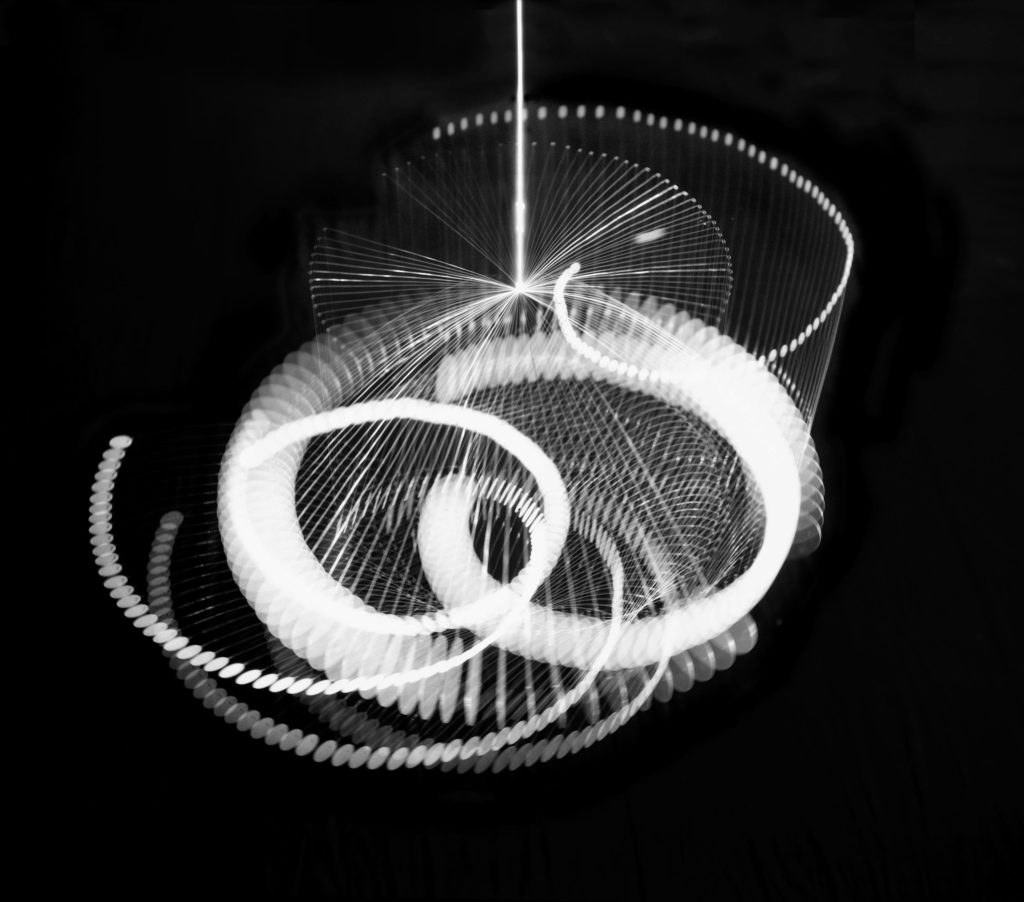

In the late 1930s and 1940s, Matter was fascinated by the possibilities of photographing movement; his work was included in a 1943 exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art, Action Photography. In his first film about Calder, prepared for the Museum of Modern Art in 1944, his taste for action led him to place, one by one, five Calders on a turntable and spin each of them around for the camera. Writing the same year in the magazine Arts & Architecture, Matter argued that, “through microscopic, astronomical, high speed, stroboscopic, x-ray, and infra-red photography we see what the human eye fails to discern. We stop and analyze the fastest motion. We grasp the split second in which the human drama is unconsciously revealed…. Our vision is quickened, our plastic conception enriched.”[5] Matter photographed hands and whole figures in motion and found a way to photograph the paths left by electrical currents.

Matter, with his passion for all things kinetic, obviously responded instinctively to a Calder such as Swizzle Sticks, which he photographed in 1936 as an abstract dance event. This man, who in the late 1940s would capture in single photographs the movements of an Indian dancer, Pravina Vashti, surely recognized the revolution Calder was bringing about in sculpture. By setting stable objects in motion Calder turned the work of art into the protagonist in a dramatic narrative. Although the origins of this revolution can never be precisely defined, it certainly had something to do with Calder’s deep-seated theatrical sense. Alexander Stirling Calder, the artist’s father, had been besotted with the theater from the time he was a boy, and he gave his son an abiding feeling for the dramatic arts. As children, Calder and his sister were introduced to well-known actors; new developments in the theater were closely monitored, especially the work of George Bernard Shaw; and it was characteristic that when Calder fell ill after college and went home for a spell, the entertainment was a family reading of King Lear. Calder first made a bit of money as an artist by doing drawings of the circus and a wide range of athletic and popular theatrical events for New York’s National Police Gazette.

When Calder began making objects that moved, he gave sculpture a new theatricality—and who can doubt that he saw the play of light and dark as integral to this drama. For a brief time in 1924, Calder had been a stagehand at the Provincetown Players. He had worked for the important theatrical designer Cleon Throckmorton, whose productions of Eugene O’Neill’s plays were known for their extraordinary lighting, with expressionist shadows that enveloped the actors in a near abstract design. The year after Matter’s first sessions in Calder’s studio, when Calder had a show at the Mayor Gallery in London, at least one journalist saw the artist play with a flashlight in the gallery, shining a spotlight on wire and metal elements to create patterns on the walls perhaps not unlike those Matter had created on the walls of the Upper East Side storefront. Both Calder and Matter could have seen affinities, however distant, with the shadow puppets that had been featured in nineteenth-century avant-garde cabarets such as Le Chat Noir in Paris and that had influenced the formal inventions of Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, Edgar Degas, Pierre Bonnard, and Pablo Picasso. Calder would remain fascinated by the theater all his life. He produced sets for Martha Graham and others, beginning in the 1930s. He created a vast acoustical ceiling of floating panels for an auditorium in Caracas in the early 1950s. And in Rome in 1968 he mounted a ballet without dancers, Work in Progress, embodying the hopes for a new kind of abstract dramatic art—an art of form, light, movement, and music—that had circulated in Greenwich Village when he was young.

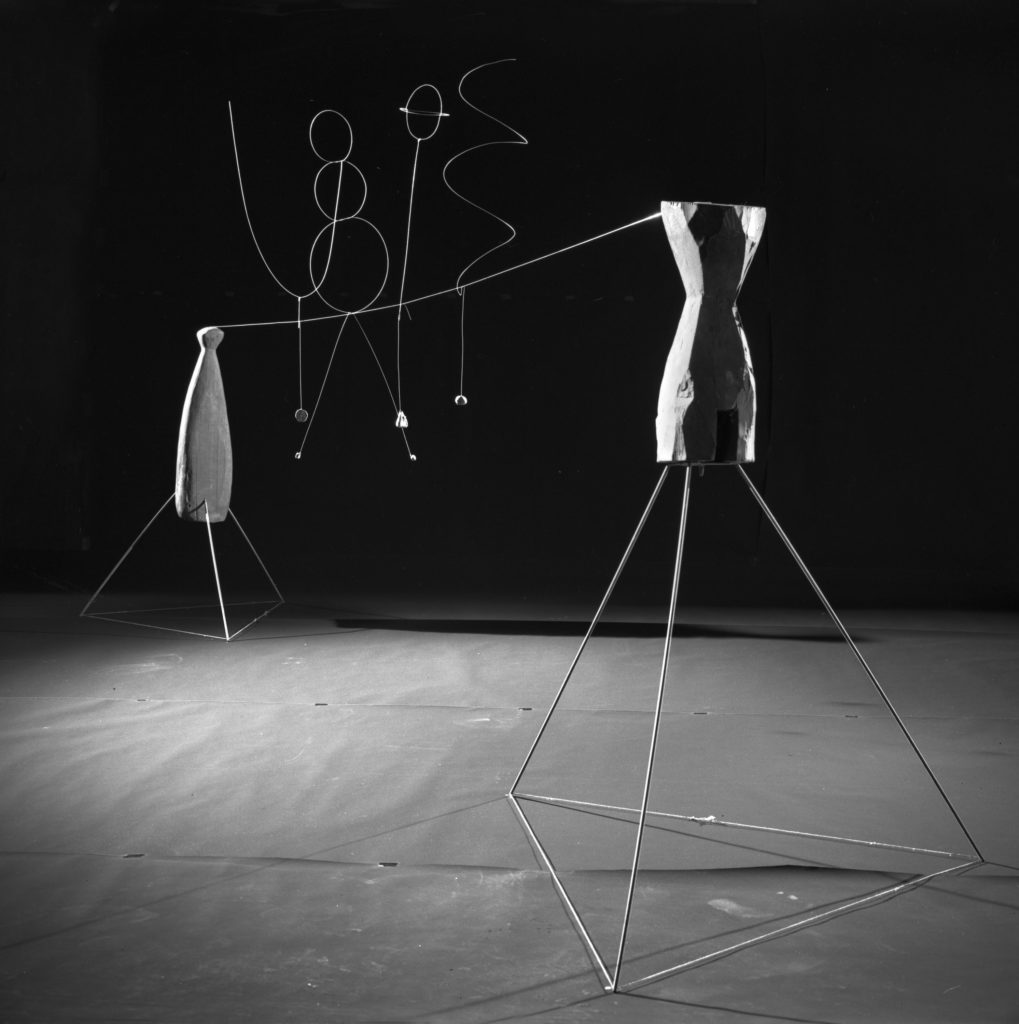

Nowhere in Matter’s encounters with Calder’s work is the theatrical sense stronger than in a photograph of Tightrope (1936), taken in 1943 for the exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art. This is one of Calder’s most unusual inventions, with two ebony and wire tripods set some ten feet apart and four enigmatic wire abstract personages suspended in between. Here Calder’s earlier immersion in the world of acrobats and other athletes is cross-fertilized with his more recent preoccupation with the signs and symbols of abstract art—and neither the naturalistic nor the anti-naturalistic impulse is allowed to quite win the day. Matter sets Tightrope in a darkened space, as if we were seeing a group of actors illuminated on a darkened stage. The tripods and the quizzical, calligraphic forms suspended on the tightrope are treated as theatrical presences, inanimate forms animated through the hyperbolic presentation. The sharp light transfigures ordinary materials, so that Calder’s bent and twisted lengths of wire achieve a thrilling immateriality. We know that when brilliantly lit beneath the proscenium arch, actors and actresses we might hardly notice on a city street can become classical gods and heroes. Calder’s abstract acrobats, abetted by Matter’s photographic aplomb, weave an unforgettable archaic drama.

When Matter photographs Calder’s mobiles and motorized sculptures, he really casts a spell. Using stroboscopic techniques, Matter sets The White Frame (1934) and Dancers and Sphere (1938) in motion. And the result is a visual echo chamber, the elements fixed in their intricate dance. In the catalogue of the 1943 Museum of Modern Art exhibition, there is a spectacular full-page spread of six of Matter’s motion studies of a mobile with eight elements, the light circular forms set off by the enveloping darkness. At top left the mobile is still. Then it is set in motion, and the clarity of forms yields to the blurring of contours. Then the blurring of contours gives way to circling patterns of light, and we are face-to-face with Calder’s triumphant infusion of life into heretofore lifeless material. Three years later, one photograph from the series was used as the cover for the catalogue of Calder’s exhibition at Galerie Louis Carré in Paris, which included the first publication of Jean-Paul Sartre’s brief, revelatory essay. Nobody has written about the kinetic power of the mobiles as convincingly as Sartre, who speaks of them as if they were superb dancers or actors, implicitly associating Calder’s kinetic inventions with the ancient enigmas of automatons and marionettes. Sartre writes that these mobiles “have a life of their own.” He says, “At times their movements seem to have a purpose and at times they seem to have lost their train of thought along the way and lapsed into a silly swaying.” At one moment the work is quiet. A moment later, Sartre explains, without any warning, it is “violently agitated.”[6] Matter photographs precisely what Sartre describes, this uncanny sense of the elements in Calder’s mobiles as engaged in a journey of self-discovery.

Matter grasped the secret life of sculptural forms, and not only when he was working with Calder. He would continue to explore related themes through his studies of Alberto Giacometti’s sculpture in the 1950s and 1960s, a project initiated by Pierre Matisse, who had been Calder’s dealer in the 1930s and early 1940s and had exhibited Matter’s photographs. Giacometti, like Calder, became friends with Matter and his wife; a book of the Giacometti photographs, with a text by Mercedes Matter, was published in 1987, three years after Herbert’s death. Matter had pondered the Giacometti book for many years, his creative process protracted, as indeed it had been on the film Works of Calder. Matter’s engagement with both Calder’s and Giacometti’s sculpture can be understood as part of a wider effort on the part of photographers to demonstrate that sculptural form has a more than formal power. We see related ambitions reflected in Charles Sheeler’s and Walker Evans’s documentations of African sculpture, in Paul Strand’s interpretations of the statues of Christ in the old Mexican churches, and in Brassaï’s studies of Picasso’s busts and figures of Marie-Thérèse Walter. Around the time of his show at the Galerie Louis Carré in 1946, Calder observed in a letter that Brassaï, who had photographed the Cirque Calder years earlier, might be a possibility to photograph his work again.[7]

What Sheeler, Evans, Strand, and Brassaï shared with Matter was a sense of the photographer as an alchemist revealing the transcendent dimensions of sculptural forms. In the nineteenth century there were photographers who claimed to catch the afterimages of ghosts and spirits, although of course that was nothing but clever camera movements and subtly altered negatives. With Herbert Matter’s photographs of Calder’s sculpture we are in the presence of genuine spirit photographs. We see the unseen. We know the unknowable. Matter embraces the true spirit of Calder’s mobiles and stabiles and constellations: the heroic ambitions, the quivering complexities, the plangent poetry.

Hauser & Wirth, Somerset, England. Calder: From the Stony River to the Sky. Exhibition catalogue. 2018.

Susan Braeuer Dam, For the Open Air

Jessica Holmes, More than Beautiful: Politics and Ritual in Calder’s Domestic Items

Solo Exhibition Catalogue“Calder in France.” Cahiers d’Art, no. 1 (2015). Edited by Alexander S. C. Rower.

Susan Braeuer Dam, Calder in France

Robert Melvin Rubin, An Architecture of Making: Saché and Roxbury

Agnès Varda in conversation with Joan Simon

Magazine, MonographMusée Picasso, Paris. Calder-Picasso. Exhibition catalogue. 2019.

Bernard Ruiz-Picasso and Alexander S. C. Rower, Confronting the Void

Chus Martinez, No Feeling Is Final

Group Exhibition Catalogue“Calder in France.” Cahiers d’Art, no. 1 (2015). Edited by Alexander S. C. Rower.

Susan Braeuer Dam, Calder in France

Robert Melvin Rubin, An Architecture of Making: Saché and Roxbury

Agnès Varda in conversation with Joan Simon

Magazine, Monograph