The art of Calder is the sublimation of a tree in the wind.

Marcel Duchamp[1]

The landscape has a unifying power for poets, painters, and sculptors alike. For William Wordsworth and Samuel Taylor Coleridge, it was the undulating hills of Somerset, where they composed Lyrical Ballads in the 1790s, unearthing the dignity in the everyday. For Thomas Cole, it was the expanse of the Hudson Valley in mid-nineteenth century New York, where he stridently captured the minutia and grandeur of the Catskills. For Alexander Calder, it was the unfolding vistas of Roxbury, Connecticut, in the 1930s, where he unleashed his mobiles into the open air, engaging the caprices of nature. As philosopher Edmund Burke declared in 1757, “Greatness of dimension is a powerful cause of the sublime.”[2] In Roxbury, the dimensions of Calder’s sculpture responded to the scale of his new environment both in size and sensibility, resulting in objects unruly, untameable, and downright revolutionary.

In July 1933, Calder and his wife, Louisa, returned to the United States from Paris—the city in which they had lived since they were married two years earlier—with the desire to start a family. They set out to find a house in the country close to New York City, where they planned to winter. After searching in Massachusetts, along the Hudson Valley, and on Long Island, the Calders turned to Connecticut, first visiting Westport—where their friend Robert Josephy, an influential book designer, lived—then Sandy Hook. The next day they made their way further inland to Danbury, where they met with an agent’s assistant who took them to Roxbury, a rural town in Litchfield County. Here, as they crested the brow of a hill on Painter Hill Road, they caught sight of a derelict eighteenth-century farmhouse. At once they exclaimed, “That’s it!” (in his autobiography, Calder maintained that it was he who said it first). “We walked out in the pasture and saw a great rocky mound on top of a gentle hill,” he described. “That sealed it.”[3] The Calders purchased the property in September 1933, it later becoming the artist’s headquarters after his career exploded internationally following World War II.

Before the move to Roxbury, Calder had already achieved a “greatness of dimension” that transformed the entire landscape of modern art. In 1931, after having worked on his Cirque Calder (1926–31) and wire objects for five years, Calder introduced the fourth dimension of time into sculpture, using motors to diversify the spatial and temporal relationships of abstract elements.[4] It was Marcel Duchamp who coined the term “mobile” (a pun which, in French, refers to both “motive” and “motion”) for these works during a visit to Calder’s Montparnasse studio that autumn. Among the first of these mobiles was Two Spheres (1931), a work severely abstract in its constitution, comprising of two spheres painted white, a repurposed black wooden panel, and a motor that moves the spheres in deliberate yet counterintuitive motions. When a reporter writing for the New York World-Telegram likened this work to a shooting-gallery target, Calder rejoined:

The balls in a shooting gallery move for a utilitarian purpose. This has no utility and no meaning. It is simply beautiful. It has a great emotional effect if you understand it. Of course, if it meant anything, it would be easier to understand, but it would not be worthwhile.[5]

What Calder was asking the perplexed reporter to do in 1932 was as challenging then as it is now: to not only leave aside preconceptions and engage in an unalloyed experience in present time but to also recognize how something that has “no meaning” can be intensely emotional. As Calder biographer Jed Perl points out, Calder’s statement is on par with what English critic Clive Bell wrote when characterizing a “significant form”—an object that produces “an emotion more profound and far more sublime than any that can be given by the description of facts and ideas.”[6] Though intimate in size and minimalist in spirit, Two Spheres was grand in its imaginative force.

Calder was no stranger to the profound and the sublime. These themes formed the basis of one of his most fabled aesthetic experiences, dating to 9 June 1922, which resonated throughout his career. “When there is some particularly dramatic effect of nature I am always willing to stay up for that,” Calder wrote, “and I remember a very beautiful hot red sunrise off Guatemala with a pale tin moon on the opposite side, a deep blue sky, and the sea all about us.”[7] While serving as a fireman on the H.F. Alexander, sailing from New York to San Francisco via the Panama Canal, Calder experienced the onset of Civil Twilight, the only time during the lunar cycle when a full moon is situated directly opposite the sun, creating an optical illusion in which the moon appears much larger to the eye. “It left me with a lasting sensation of the solar system,” Calder concluded.[8] The term “sensation” is operative here, suggesting a visceral communion with nature’s magnitudes—something akin to what his mobiles would later generate in their beholders.

During that sublime moment off the coast of Guatemala, Calder transcended multiple thresholds, conspiring with nature’s rapid transformations. He was struck not merely by the dialectical ballet between the sun and the moon, the free-flowing sea and the rotating earth, and the eye and the horizon, but by the circumference of the unseen—a binding force—that circulated infinitely outward, without beginning or ending. As Calder wrote, “The idea of detached bodies floating in space, of different sizes and densities, perhaps of different colors and temperatures, and surrounded and interlarded with wisps of gaseous condition, and some at rest, while others move in peculiar manners, seems to me the ideal source of form.”[9] With no fixed, identifiable content, Calder’s mobiles were not about imitation, but immediacy; they were not about nature, but the nature of all things.

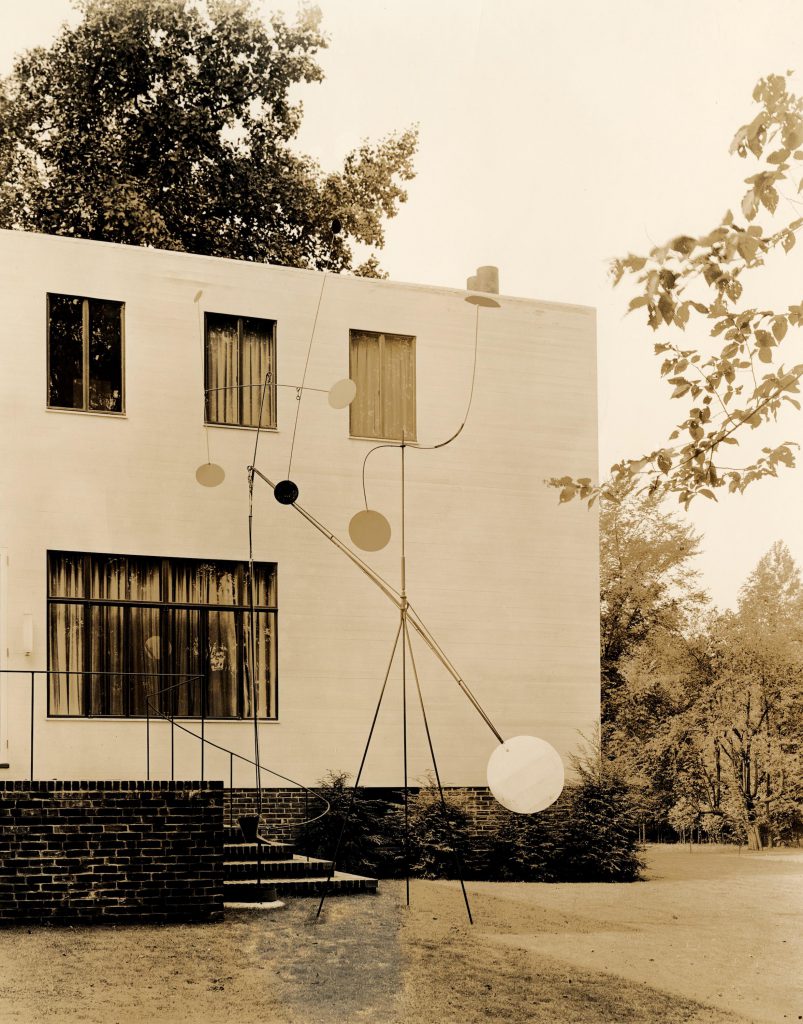

With the departure from his Paris studio and the move to the verdant countryside of Roxbury, Calder’s motorized mobiles developed into immense, wind-propelled volumes in space. In the summer of 1934 (less than a year after buying the Roxbury house), Calder made his first works for the outdoors, ranging in height from five- to nine-feet tall.[10] Red and Yellow Vane and Red, White, Black and Brass were agile constructions with mobile elements atop tripod legs that could be firmly embedded in the soil. Made from materials typically used for indoor works, and buoyant in stature, they were unable to tolerate strong winds, so Calder had to bring them indoors when the weather dictated. Steel Fish, Calder’s first welded work for the outdoors, was more resilient, with rods of a larger gauge. “I have made a number of things for the open air,” Calder recounted in The Painter’s Object. “All of them react to the wind, and are like a sailing vessel in that they react best to one kind of breeze.”[11] By the end of 1936, Calder had completed two private commissions for outdoor works, among them the twenty-two-foot-tall Well Sweep (1936) for the Greek Revival home of collector James Thrall Soby (remodeled by architectural historian Henry-Russell Hitchcock) in Farmington, Connecticut.[12] At the time, Soby was an advisor to Arthur Everett “Chick” Austin, Jr. at the Wadsworth Atheneum in Hartford, Connecticut, and a major supporter of Calder’s work.

Like Two Spheres and the Parisian abstractions that came before, Red and Yellow Vane and Steel Fish were entirely nonobjective. Calder titled the works after their completion with a vague description of their form, a common practice for the artist. In Steel Fish, the large steel shape for which the work was likely named carries broad implications, having appeared in various manifestations in his abstract work from the early 1930s. As the artist wrote around this time, describing how art can be realized, “Spaces, volumes, suggested by the smallest means in contrast to their mass, or even including them, juxtaposed, pierced by vectors, crossed by speeds. Nothing at all of this is fixed.”[13] In 1935, a similarly abstract shape appeared in an etching entitled Grandeur-Immense, the title of which refers not only to an idea of scale but also evokes traditional notions of the sublime.[14] Far from a traditionalist, however, Calder expressed nature’s totality in his sculpture not by adding layer upon layer (in the manner of an eighteenth-century allegorical landscape), but by a method of simplification, at once bold and succinct. By reducing the seen, Calder illuminates the unseen, giving prominence to relationships over things, to immateriality over materiality, to the energetic forces that open new fields of experience.

“Just as Calder’s wire sculpture, predominately two-dimensional at the outset, came to suggest transparent volumes,” wrote art historian and curator James Johnson Sweeney, “such large-scale, free-swinging mobiles as the Steel Fish now began to describe, with gestures like a dancer, volumes in space.”[15] The summer Calder created Steel Fish, he brought the gestures of dance into the outdoors by collaborating with choreographer Martha Graham. Visiting her at Snake Hill Barn near Stamford, Connecticut, he enlarged what he described as a “ballet-object,” or a kinetic theatrical maquette without dancers (a concept that began back in Paris in spring 1933). “I tried it [in] the open air, swung between trees on ropes,” Calder wrote in The Painter’s Object, “and later Martha Graham and I projected a ballet on these lines. For me, increase in size—working full-scale in this way—is very interesting.”[16] The project was a prelude to Graham’s Panorama (1935), which premiered the following summer in Bennington, Vermont, and featured Calder’s mobiles. Calder and Graham also collaborated on Horizons, which premiered in February 1936 at the Guild Theatre in New York City, for which Calder made six mobiles or “visual preludes.”[17] Just a week before this, Calder debuted his kinetic decor for Erik Satie’s symphonic drama Socrate (commissioned by composer Virgil Thomson and Chick Austin) during the First Hartford Music Festival at the Wadsworth Atheneum.

A number of photographs from this period capture Calder in the process of installing his outdoor works in Roxbury, highlighting the elemental landscape. In one picture from 1934, taken by Soby, Calder stands next to Steel Fish on the hill behind the farmhouse, with its large steel form waiting to be “crossed by speeds.” Swiss photographer Herbert Matter also photographed Calder assembling Five Rods and Nine Discs (1936), a fifteen-foot-tall standing mobile that the artist made for his property. In a few of these images, the expansive Steel Fish can be seen in the background. Like Red and Yellow Vane and Red, White, Black and Brass, Five Rods and Nine Discs was anchored in the soil; its mobile element hung from a post made from pipes of decreasing diameter, suggesting a divining rod of sublunary forces. What Matter’s photographs capture are pivotal moments in the trajectory of Calder’s career, moments in which he surrenders his control as an artist to the unseen forces of nature. “A landscape doesn’t demand from the spectator his ‘understanding’, his imputations of significance, his anxieties and sympathies,” writes Susan Sontag. “It demands, rather, his absence.”[18]

Living and working in the open air instigated a groundbreaking working process for Calder. By 1936, he realized that making mistakes on a large scale was as expensive as it was unproductive, so he began creating maquettes or scale models. The first of these was a thirty-five-inch-tall model for Devil Fish (1937), which translated to a five- and-a-half-foot-tall sculpture or “stabile” (as these stationary works were named by Jean Arp in 1932). Another was Ex-Octopus (maquette, 1936), a seventeen-inch-tall model that was enlarged to around six-feet tall, (but not until three decades later). As he later conceded in his 1943 manuscript À Propos of Measuring a Mobile, “The admission of approximation is necessary, for one cannot hope to be absolute in his precision.”[19] Calder’s acceptance of approximation contributes to the aliveness of his stationary works. Depending on our perspective, his stabiles, with their fluid and organic curves, assume a new face at each turn, their elements unfolding in perpetuity as if in a state of continual becoming.

The maquette for Ex-Octopus, along with Devil Fish and its model, premiered in Calder: Stabiles & Mobiles at Pierre Matisse Gallery, New York, in winter 1937, the artist’s third solo show with the legendary dealer since 1934. Here, he installed a number of maquettes at the feet of Big Bird (1937) with the intention of enticing patrons to commission large-scale sculptures for their gardens. In spring 1940, in what was his fifth solo show at Matisse’s gallery, Calder premiered Black Beast (1940), an angular, menacing stabile that stood at nearly fourteen-feet wide and nine-feet tall. Seventeen years later, Calder made Black Beast II (1957) in a heavier material—using a thick gauge iron plate—for the courtyard of architect Eliot Noyes’ home in New Canaan, Connecticut. As the artist recalled in his autobiography, it was Black Beast and Devil Fish, along with the standing mobile Spherical Triangle (1938), that counted as “the forerunners of the big stabiles to come.”[20]

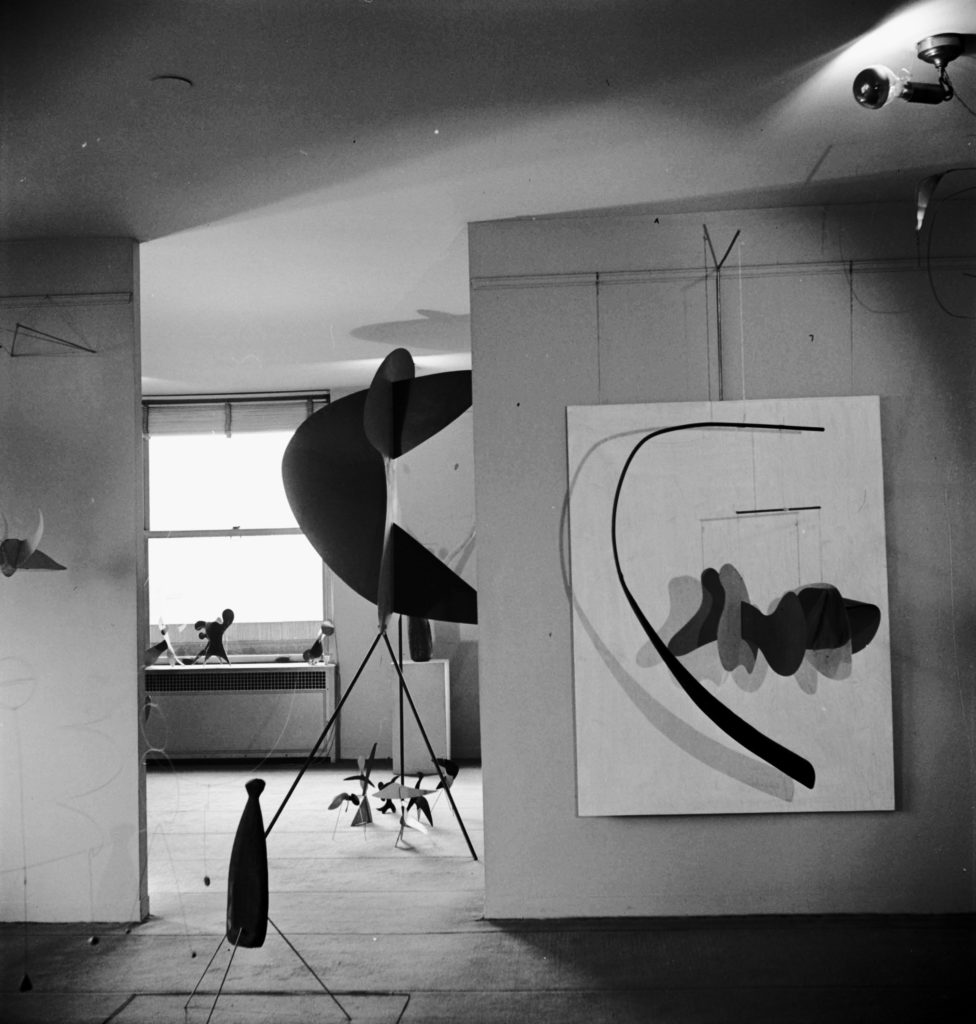

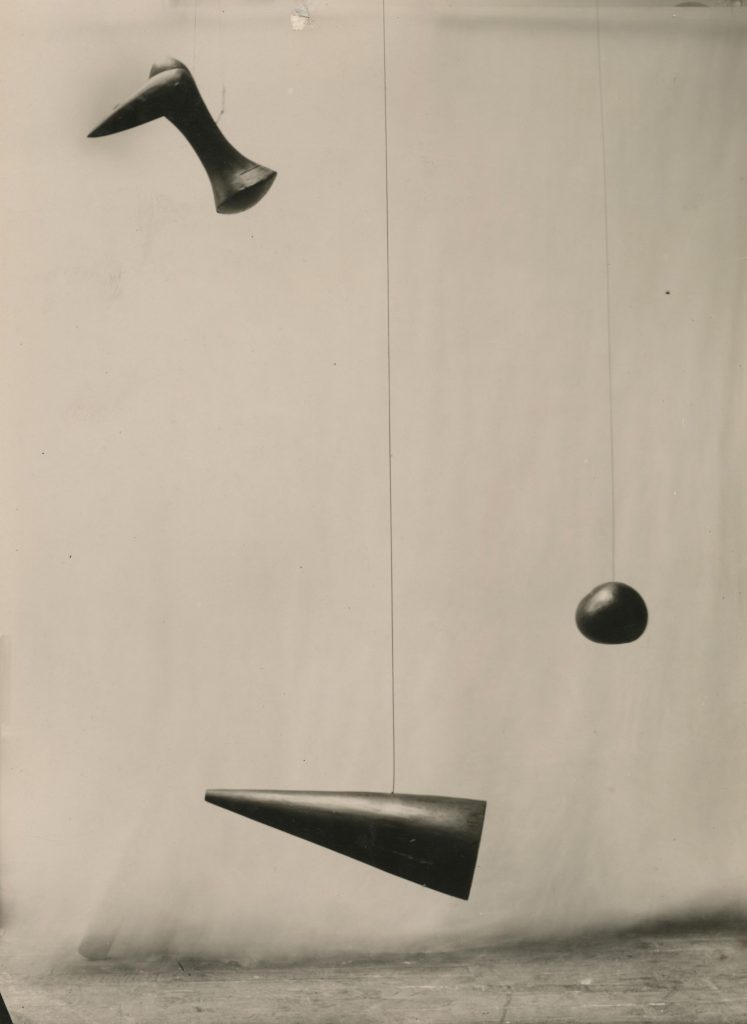

Calder’s entire oeuvre is marked by dramatic shifts in media, style, and scale, and his early inventions in Roxbury were no exception. Just as the open air encouraged an increase in size in his outdoor works, it also instigated a lightness of form in his indoor creations. Starfish (1934) was among the earliest manifestations of the hanging mobiles that Calder made in Roxbury. While it formally recalls Cône d’ébène (1933), the last of Calder’s hanging mobiles made in Paris, it is strikingly different in execution and sensibility. Starfish is refined, complex, and more sophisticated in its tension with gravity, whereas Cône d’ébène is coarse and lumbering, made of solid ebony. In other works from around 1934, Calder suspended delicate, energy-dense wooden elements from strings, allowing for greater movement. The lighter Calder’s mobiles became, the more unpredictable the expanse of their dimensions and the character of their motions.

For Starfish, Calder carved directly into wood, a practice he began in the mid-1920s in New York with his figurative works. He often used wood in his abstract sculptures of the 1930s, such as Untitled (1935), for which he reckoned with the grain to make forms at once agile and exotic. Seven years later, when sheet metal was in short supply during World War II, Calder went so far as to destroy one of his conventional wood sculptures from 1929 (entitled The Crowd) in an act of extreme recycling, so that its ebony pieces could serve as the basis for his “Constellations” (so-named by Sweeney and Duchamp). These abstract wood and wire sculptures premiered in 1943 in what would become Calder’s last show with Matisse: Calder: Constellationes. “They had a suggestion of some kind of cosmic nuclear gases—which I won’t try to explain,” Calder recalled. “I was interested in the extremely delicate, open composition.”[21] Untitled (1945), which includes a variation on an ovoid-like form as a unifying force in resonance with Steel Fish, postdates his foray into the Constellations.

Calder always had a deep affinity for humble materials (his Cirque Calder was crafted from a wide spectrum of them), and he expanded upon this interest in Roxbury in surprising ways. Having stumbled upon a dumping ground used by previous homesteaders, Calder began to make mobiles with shards of colored glass, bits of broken pottery, and pieces of metal that could be set in motion by the slightest breath of air. In a work such as Tines (1943), which includes tines snapped off a pitchfork, as well as the stem of a broken wine glass, Calder engaged luminous and sonorous energy. The mobile not only reflects and refracts light, but its elements collide at surprising moments, creating delicate pinging sounds. The frequencies of light and sound that reverberate in Tines give new meaning to Calder’s conviction that a “mobile in motion leaves an invisible wake behind it, or rather, each element leaves an individual wake behind its individual self.”[22] Even after the direct act of experience is over, the mobile does not cease its work on us.

Writing on Calder’s development in Roxbury, Sweeney remarked: “Little by little, calculated forms gave way to forms suggested by the material—a lump of wood, a piece of bone—till finally the materials employed seemed scarcely touched by tools.”[23] Nowhere is Calder’s intuition of material more astonishing than in Apple Monster (1938), an object made from the fallen branch of an ancient apple tree at Roxbury that the artist turned upside down and modified to create a Surrealist personage. The energy emanating from this work is twofold: it is at once a relic of the Roxbury property and an object that gives us insight into the artistic act of seeing. As Brazilian art critic Mário Pedrosa intimated, “[Calder] was able to draw from wood as if moved by some divine sense or mysterious faculty for intimate communication with things, his hands deprived of any tool, like those of a magician.”[24] In its untitled sister sculpture from that year—nicknamed “Vertebra Monster” by Calder Foundation employees—Calder incorporated a cow vertebra which he had found on the property. Perched atop the sculpture’s back is a progeny of spheres that vibrate when activated, creating a contrapuntal value that harkens back to some of his earliest abstractions from Paris, among them Croisière (1931).

Another sculpture from this tribe, Praying Mantis (1936), was exhibited in Alfred H. Barr, Jr.’s Fantastic Art, Dada and Surrealism at the Museum of Modern Art, New York in 1936. Calder was also represented in Barr’s Cubism and Abstract Art mounted the previous spring at the museum. In his remarks on abstract art for the accompanying catalog, Barr quoted Plato’s Philebus:

I will try to speak of the beauty of shapes, and I do not mean, as most people would think, the shapes of living figures, or their imitations in paintings, but I mean straight lines and curves and the shapes made from them, flat or solid, by the lathe, ruler and square … These are not beautiful for any particular reason or purpose, as other things are, but are always by their very nature beautiful, and give pleasure of their own quite free from the itch of desire.[25]

Coincidentally, Plato’s statement not only resonates with what Calder said about Two Spheres in 1932 (“This has no utility and no meaning. It is simply beautiful.”), but also appears in what Duchamp wrote about Calder’s work in 1949, published the following year in the Collection of the Société Anonyme: “In their treatment of gravity, disturbed by gentle movements, [the mobiles] give the feeling that ‘they carry pleasures peculiar to themselves, which are quite unlike the pleasures of scratching’, to quote Plato in his Philebus.”[26]

Although Calder did not intentionally align his work with the ideals of Surrealist automatism, there is something automatic in his immediate way of creating, as expressed in these works from 1938. Calder was also drawn to the energetic dimensions of single-line drawing, and Coleridge’s The Rime of the Ancient Mariner, published in the first edition of Lyrical Ballads in 1798, counted among his projects. This poem, supposedly inspired during Coleridge’s walks through Somerset’s Quantock Hills, was a favorite of the Surrealists, with its supernatural descriptions of “the sky and the sea” all but capsizing a boat and its inhabitants. The 1946 special edition included 29 single-line etchings by Calder, among them seascapes and setting suns that hark back to Calder’s fabled experience off the coast of Guatemala.[27] What Robert Penn Warren wrote about the meaning of a poem in his accompanying essay for The Rime of the Ancient Mariner could very well apply to the mobile: “We may say that the reader does not interpret the poem but the poem interprets the reader. We may say that the poem is the light and not the thing seen by the light. The poem is the light by which the reader may view and review all the area of experience with which he is acquainted.”[28] Perhaps the sublime lies not in an object itself—in the greatness of measurable dimensions—but in the nature of the mind’s immeasurable response.

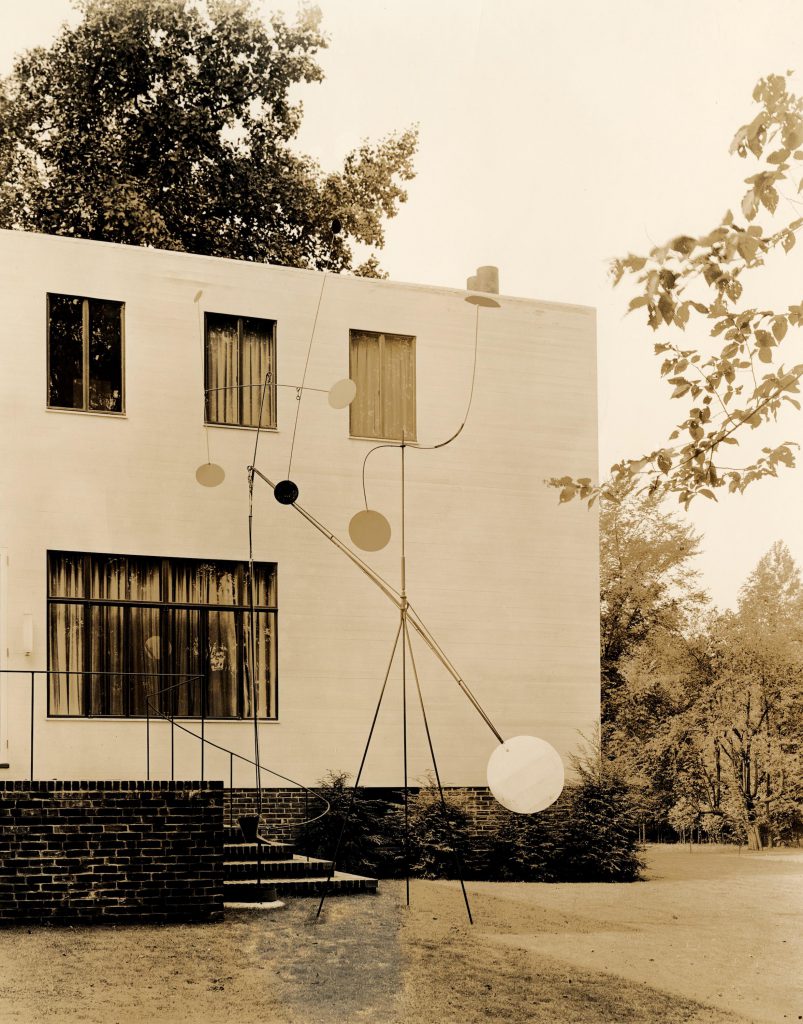

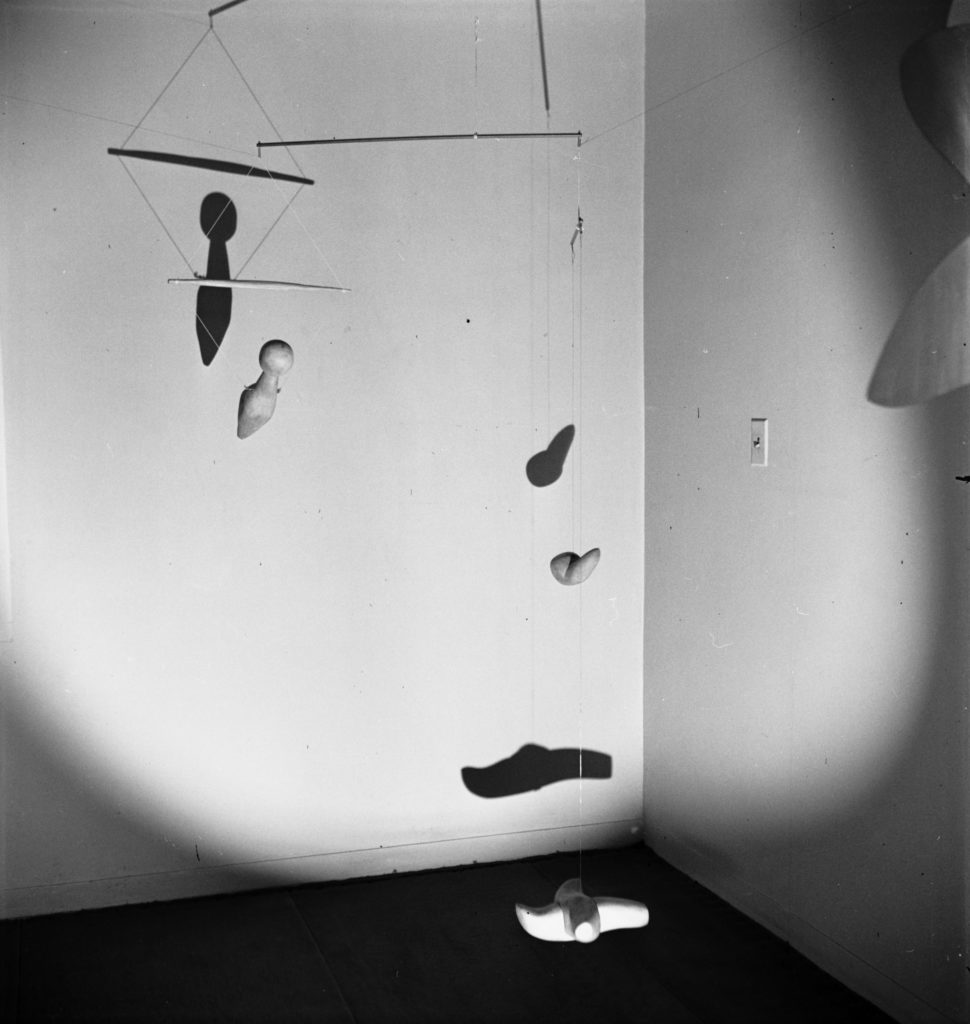

In October of 1938, Calder began building a “vast and unencumbered” studio space on the side of a hill near his Roxbury home on the foundations of the old dairy barn, which was completed the following spring.[29] At twenty-five by forty-feet, with a roof that peaked at thirty-two feet, the studio was a large reservoir that engaged a sense of continuity between art and nature. “It did not stay unencumbered for long,” wrote Calder, and it soon overflowed with all manner of mobiles, stabiles, standing mobiles, and paintings, as evidenced by Matter’s photographs from 1941.[30] An excerpt from André Masson’s handwritten poem “L’Atelier d’Alexander Calder” touches upon the incalculable synthesis of earth, light, sound, and time that reverberated throughout the space:

One green day you saw a red bird / in pursuit of a yellow bird; / you know that we are bound to nature / that we belong to the earth. / Hung from the studio’s rafters, / in the streaks of light a gong sensitive to the caprices of air / is struck only with the greatest caution / With the step of a dove it rings: what hour does it sound?[31]

Notably, Calder encouraged Rose and André Masson to relocate to Connecticut during the war years, along with Yves Tanguy and Kay Sage. Masson’s poem, which the artist wrote in Calder’s studio while sleeping on the studio bed, attests to the profundity of their friendship, Calder having been pivotal in resolving the artist’s displacement during the war. Marc Chagall, David Hare, Hans Richter, and Arshile Gorky were among some of the other artists who settled near Calder’s home in Litchfield County, and he also hosted a number of Surrealist exiles, among them André Breton. By the mid-1940s, Calder had rebuilt the bohemian community from his Paris years in Roxbury, Connecticut.

The landscape’s profound impact on Calder continued to expand in the years to come. His mobiles and standing mobiles became increasingly sophisticated, from the constantly shifting states of Untitled (Mobile with N Degrees of Freedom, 1946) to the punctured voids in Red Maze I (1954) and Untitled (1954), expressing thresholds of presence and absence. His stabiles, too, continued to grow, not only in experiential complexity but also in size. By the 1960s, he was making sculptures of a colossal scale, among them La Grande vitesse (1969), the first sculpture to be funded by the public art program of the National Endowment for the Arts, for which he made a 1:5 intermediate maquette. For Calder, art and nature remained deeply interrelated aspects of the great dimension of experience. “Not extractions,” he wrote, “but abstractions. Abstractions that are like nothing in life except in their manner of reacting.”[32]

Hauser & Wirth, Somerset, England. Calder: From the Stony River to the Sky. 26 May 2018–9 September 2018.

Solo ExhibitionHauser & Wirth, Los Angeles. Calder: Nonspace. Exhibition catalogue. 2019.

Andrew Berardini, The Cosmic Mathematics of Alexander Calder

Solo Exhibition Catalogue“Calder in France.” Cahiers d’Art, no. 1 (2015). Edited by Alexander S. C. Rower.

Susan Braeuer Dam, Calder in France

Robert Melvin Rubin, An Architecture of Making: Saché and Roxbury

Agnès Varda in conversation with Joan Simon

Magazine, MonographAlmine Rech Gallery, New York. Calder and Picasso. Exhibition catalogue. 2016.

Robert Slifkin, The Mobile Line

Susan Braeuer Dam, Liberating Lines

Jordana Mendelson, Picasso, Miró, and Calder at the 1937 Spanish Pavilion in Paris

Group Exhibition Catalogue“Calder in France.” Cahiers d’Art, no. 1 (2015). Edited by Alexander S. C. Rower.

Susan Braeuer Dam, Calder in France

Robert Melvin Rubin, An Architecture of Making: Saché and Roxbury

Agnès Varda in conversation with Joan Simon

Magazine, Monograph