Nearly a century after the debut of Alexander Calder’s wire sculpture it is difficult to imagine that these works were first considered so radical as to fall outside of the category of art. In 1928, when Calder exhibited his wire sculptures Romulus and Remus (1928) and Spring (1928), many in the art world greeted them with puzzlement. Calder’s works elevated the utilitarian material of wire to the stuff of fine art and presented a new kind of transparent object. Romulus and Remus, Spring, and the impressive Hercules and Lion (1928) were clearly meant to be taken seriously, and their size and subject matter resonated with the characteristics of traditional sculpture, but the use of wire as a medium challenged the conventional definition of sculpture as a solid mass.

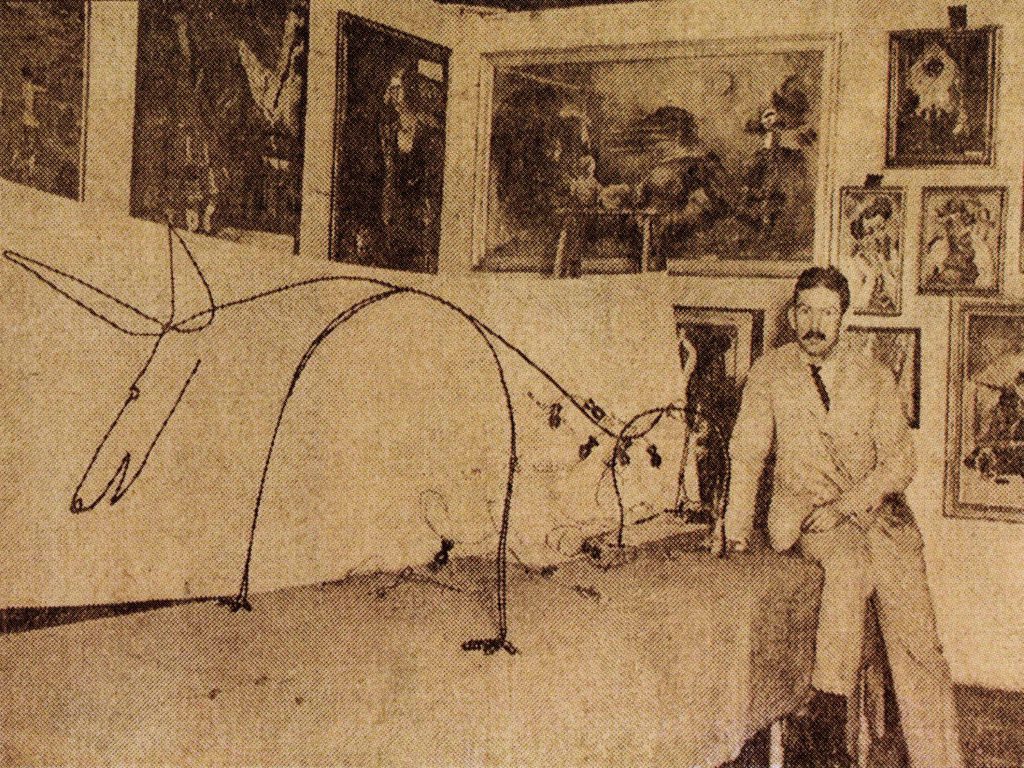

“Copper wire and bureau drawer knobs made their first appearance as mediums of artistic expression yesterday,” read the title of a New York Times article about the exhibition.[1] Another article described how bringing the works home from the exhibition Calder “created somewhat of a panic on 5th Avenue … by walking down that highway closely followed by an eleven foot wolf.” The article goes on to say, “Yes Mr. Calder considers her a work of art,” and gives his response: “‘I shouldn’t have made her if I didn’t.’”[2] Calder seems to have made Romulus and Remus, Spring, and Hercules and Lion in response to the criticism that his wire objects were not “art.” By synthesizing elements of an established sculptural tradition and his own sense of invention, these three works are Calder’s entreaty to be taken seriously as an artist. In 1929 Calder characterized his work of 1926–1927 as “merely a very amusing stunt cleverly executed,” meaning that he had not yet explored the expressive potential of the medium. But he was careful to distance these “stunts” from his “new studies in wire” that “did not remain the simple modest little things I had done [before].”[3] Indeed, the compositions of Spring, Romulus and Remus, and Hercules and Lion go beyond Calder’s earliest constructions in wire and suggest the great sculptural intentions that Calder had yet to realize.

The new approach to space seen in these three sculptures serves as a bridge that links Calder’s earliest work as an illustrator to his celebrated mobiles. Through his creation of wire figures in space, Calder discovered he could conjure up forms that embodied potential energy and indicated future possibilities. Visually, the wire sculptures are “drawings in space,”[4] but it was the more subtle aspect of these works—the way the nervous energy of a wire line is capable of activating the surrounding space through the suggestion of movement—that Calder was to explore more fully over the course of his career.

Calder grew up in a family of artists, steeped in the sculptural tradition. From an early age Calder was given a studio in the family’s cellar and tools to work with. He later remembered: “Mother and father were all for my efforts to build things myself—they approved of the homemade. I used to make all sorts of things, little seats, or a tonneau cover for my coaster wagon.”[5] In this childhood studio Calder began using wire as a medium: “I used to gather up the ends of copper wire discarded when a cable had [been] spliced, and with these and some beads would make jewellery [sic] for my sister’s dolls.”[6]

Calder arrived in Paris in the summer of 1926 intending to pursue a career as a painter, but before long he lost interest in painting and grew fascinated with “making small animals in wood and wire and articulating them.”[7] Out of these efforts came Cirque Calder, a small-scale circus designed to be manipulated by Calder in performances that could last several hours. Using wire, wood, fabric and found materials, Calder called on the tools of his engineering training to construct ingenious figures that he could propel into motion. Calder had a certain amount of control of the performance. But he purposely left some things up to chance. He activated the acrobats but there was no guarantee they would land on their feet. It was this chance of failure that made Cirque Calder compelling to watch. The art historian James Johnson Sweeney describes Calder’s performers as having “a living quality in their uncertainty.”[8] Movement is the key component of this living quality. In his circus Calder began to explore both the technical means of achieving the movements he desired, as well as how to situate those movements in space, so that his acts evoked the drama of the real-life circus.

Calder made his first formal wire sculptures Josephine Baker and Struttin’ His Stuff in 1926. Sweeney describes this new work: “They were now three-dimensional forms drawn in space by wire lines—much as if the background paper of a drawing had been cut away leaving only the lines. The same incisive grasp of essentials, the same nervous sensibility to form, and the same rhythmic organization of elements, which are virtues of a drawing, were virtues of this new medium.”[9] Calder’s ability to draw caricatures, honed in his days as an illustrator, served him well in his venturesome attempts to formulate a new medium of artistic expression.

Calder worked in wire for much of 1926 and 1927, producing many portraits and studies of animals. These earliest attempts at sculpture in wire did not yet render volume convincingly; they possessed “a certain flat frontality,” as Sweeney put it.[10] In Sea Gull, the creature is amusingly rendered but feels more like intersecting planes than a fully realized volume. Viewed from the front, the bird’s head and body disappear into a flat plane.

Calder’s style quickly evolved, as can be seen by a comparison of two works made about a year apart. Helen Wills I (1927) and Helen Wills II (1928) both depict the American tennis star Helen Wills Moody with racket in hand, reaching for a forehand shot. The first important difference between the two was size; Helen Wills II is more than two and a half times larger than Helen Wills I. The composition of the Helen Wills I centers around the leg she stands on and the lines of her body extend from this central axis, giving the sense that she is posed mid-swing. In Helen Wills II, the precarious bend of her body is made more dramatic by her exaggerated, carefully extended limbs. Rather than presenting a static figure, she seems to be rushing forward. Around her foot Calder has added a wire arc that is not only a cue to motion, but also further enlivens the composition by creating tension through the contrast with the arc of her skirt. Whereas Helen Wills I seems to focus on cleverly re-creating the elements of a tennis player in wire, Helen Wills II is an attempt to evoke a figure in a moment of action.

After more than a year in Paris, Calder decided to head back to the United States in the fall of 1927. He brought his circus and his wire works with him. In February of 1928 he had his first one-man show of wire sculpture at the Weyhe Gallery in New York. Calder recalls the experience:

There were about fifteen objects and we priced these things at ten and twenty dollars. Two or three were sold. Among those sold was the first Josephine Baker which I had made in Paris. I think it is about then that some lady critic said: “Convoluting spirals and concentric entrails; the kid is clever, but what does papa think?”[11]

Calder’s recollection is not quite exact, perhaps with good reason, as the reviewer was in fact much more harsh:

Of the wire sculpture of Alexander Calder, Jr., the best is silence. But one cannot help wondering what the academic Calder Senior thinks of all these concentric entrails and convoluted spinal columns and why the excellent Mr. Weyhe sees fit to exhibit them.[12]

The New Yorker’s critic was much more enthusiastic about Calder’s work, but even so felt the need to qualify his opinion:

[At the Weyhe Gallery] is Alexander Calder, who makes wire sculpture, almost while you wait. Only geniuses should take art seriously. The others should have more fun with it. Mr. Calder points a moral to those who spend a life hewing stone and then have nothing more than a frog or a water baby. Calder … shows a human insight missing from ninety-nine per cent of the sculpture turned out today.[13]

At the time, even Calder admitted, “I did not consider this medium to be of any signal importance in the world of art.”[14] But as he continued to develop new ways of depicting figures in wire, he began to make subtle formal innovations that would soon take shape in Spring, Romulus and Remus, and Hercules and Lion.

In the next phase of this rapidly unfolding episode of artistic innovation, Calder introduced the elements of monumentality and storytelling into his work with wire. By incorporating these elements of traditional sculpture, the new medium of wire sculpture transcended its playful and tentative origins. It took further experimentation, sometimes unsuccessful, for Calder to realize the potential of the genre, and in doing so he encountered the plight of many innovators: his thinking outstripped the imagination of art world arbiters, many of whom showed an inclination to dismiss what they did not understand.

After the show at the Weyhe Gallery, Calder returned to his studio and concentrated on making new wire sculpture:

I also remember making a seven-foot-tall lady, holding a green flower, whom I called Spring—it was in the spring of 1928. I also made, during the same period, an eleven foot she-wolf, complete with Romulus and Remus. To embellish either sex, I used doorstops I had bought at the five-and-ten—wood and rubber. These two wire sculptures I exhibited in the New York Salon des Indépendants, at the old Waldorf Hotel on Thirty-fourth Street.[15]

In Spring, Calder incorporated a narrative quality previously unseen in his work: the allegory of spring, a young woman holding a freshly picked flower. The title is also a pun on the wire medium, for her body is literally a spring—when the work is pulled forward and let go, it bounces back and forth on its pedestal. Another difference between Spring and previous works was scale: Spring is larger than life at over seven feet tall which gives the work a monumentality commonly observed in academic sculptures, like Stirling’s George Washington. Calder’s Spring was clearly an attempt to engage the tradition of his father and grandfather, and to update it.

Spring was not entirely successful as a work of sculpture. Most of its failures are easy to see upon comparison with the later wire sculpture, Acrobat (1929). The size of Spring, though important to understanding Calder’s intentions, hinders his depiction of the body; her elongated limbs seem static rather than capturing arrested movement. By contrast, Acrobat measures a more manageable (but not so grand) two and a half feet tall. The dramatic “X” shaped pose of the acrobat is emphasized in wires that criss-cross at her middle, and taken together they give an internal rhythm to the sculpture. Acrobat successfully evokes a three-dimensional volume. Spring feels stiff and flat by comparison; there is no rhythmic harmony in the lines of her body.

Even larger than Spring, Romulus and Remus shared the same elements of epic scale and storytelling, in this case the familiar myth of the founders of Rome. Cast out of their home as newborns, they are put in a basket and sent down the Tiber River to certain death. But a series of divine circumstances saves the twin boys. First, a fig tree snags their basket, then a female wolf carries them from the basket and nurses them, until a passing shepherd takes them home and raises them as his own sons. The well-known image of Romulus and Remus nursing from the she-wolf is most famously depicted in the Lupa Capitolina, a bronze from around 500 B.C.[16]

Calder struggled with some of the same problems of scale in Romulus and Remus as he did in Spring, mostly in the large body of the she-wolf. Her body reads as a single plane from nose to tail, intersected by perpendicular planes at her ears, front legs, and back legs. Her ears and legs are themselves overly symmetrical. The effect is two dimensional—the “flat frontality” that Sweeney describes. The babies come more fully to life in their three-dimensionality. The curves in their bodies and the prominent “O” of their mouths give a sense of ascending energy and the urgency of hungry infants.

Calder brought the works to the Waldorf-Astoria, to exhibit them at the New York Society of Independent Artists Twelfth Annual Exhibition in March of 1928. He found some difficulty with the installation:

The she-wolf necessitated two tables arranged end to end. I went home and got a piece of blue denim to put under Romulus and Remus and the she-wolf, in order to unify the tables. Later, I went home and had dinner. Returning to the Waldorf, I discovered somebody had used the space beneath the wolf to display some yellow dishes.

I objected.

The dishes were removed.[17]

The yellow dishes would have been an interruption to the experience of viewing the sculpture. Because of the transparency of a wire work, Calder always had to consider the space around it. His objection to the dishes makes it clear that, even in 1928, he considered this surrounding space to be active and crucial to viewing the work. The energetic line in Calder’s wire sculpture is capable of activating the space around it in anticipation of motion. The figures are evoked in moments of action, so the sculpture becomes more than just the lines of which it is composed, but the trajectories of those lines. The wire describes not only one position in one moment but gives an impression of a future moment, and a sense of anticipation of future positions.

Around this time Calder created Hercules and Lion, a third wire sculpture that has much in common with Spring and Romulus and Remus.[18] Hercules and Lion is the largest wire sculpture meant to be suspended from the ceiling; though at around five feet tall, it is not nearly as large as Romulus and Remus or Spring. Because of the light materials and the openness of the composition, the work gently rotates with currents of air. The motion adds dynamism to the sculpture, but it also allows the viewer to engage the work from different sides.

For Hercules and Lion, Calder again chose mythological subject matter in the story of Hercules who must battle the Nemean lion on the first of his twelve labors. With its indestructible fur, the lion cannot be hurt by weapons, so Hercules catches the beast in its cave and strangles it with his bare hands.

Calder magnified the hero’s strength in the giant size of his neck and chest. But the relatively skinny wires that form the arms are so at odds with the torso that they seem less a depiction of actual limbs and more of a framework for the strength and energy of his body. Calder used the transparency of wire sculpture to overlap the bodies of Hercules and the lion, so that Hercules’ lower half is visible through the lion’s face. The design is somewhat difficult to decipher, as Hercules’ hands get mixed up with the lion’s face and paw. This impression is exaggerated by the actual motion of the work—as it slowly spins, parts become clear or fade away. Above all the wire lines are expressive, but instead of neatly describing features they suggest the chaotic energy of battle.

Calder returned to Paris in the winter of 1928 and soon exhibited Romulus and Remus and Spring at the Salon des Indépendants held at the Grand Palais. The latter work was now titled Printemps, the French word for the season, but the original pun was lost in translation.

Some critics were not sure what to think:

Mr. Alexander Calder’s wire dolls and animals get a laugh from everybody, although their place in an art salon might be questioned. They are a [sic] least refreshing and clever.[19]

The only submission a little revolutionary was without doubt the “wire sculpture” of Alexander Calder who will maybe make his own school! … They bear witness less to the spirit of research than an evident sincerity.[20]

Some were even more favorable:

Moreover, there are two works of an important dimension: a she-wolf suckling Romulus and Remus and le Printemps, a long nude woman who sniffs a flower. Only, they are in wire. Look at them all the same. Who knows if the sculpture of Mr. Calder is not that of the future? In any case, it won’t spawn melancholy.[21]

A humoriste, at last, the huge success of foolish laughter at the present Salon: Calder…. This drawing in space, Calder … uses it with the lovely verve of a caricaturist and maybe something more.[22]

And some less so:

Lastly there are Mr. Alexander Calder’s wire sculptures, a kind of art which I appreciate little.[23]

In his early experiments with the medium of wire, Calder had begun to explore the formal possibilities of describing volume and suggesting movement. Integrating the sculptural elements of large-scale and mythological/allegorical subject matter into his open wire constructions posed many problems of conception and execution. Working them out would influence Calder’s subsequent development of the mobile, where the anticipation of movement is a crucial concern.

Shortly after the exhibition of Romulus and Remus and Spring, Calder wrote to his mother: “I brought back my stuff from the Independants today. They were a grand success, but I wish someone had bought them, for they are the dickens to house. However I have slung the wolf up near the cieling [sic] and its [sic] quite amusing to see it from below.”[24]

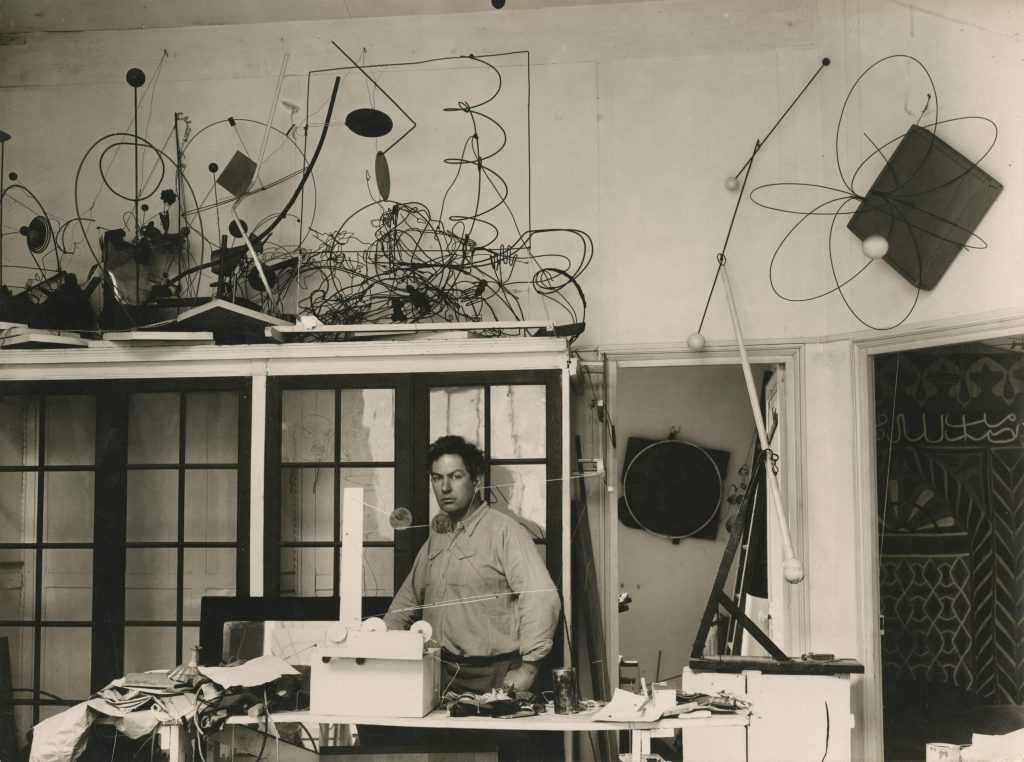

Though it does not show Calder’s studio of 1929, this photo taken by Marc Vaux in the fall of 1931 gives a good idea of how these sculptures became entangled. Romulus and Remus and Spring are visible above Calder’s head. Many decades would pass before they were again unfurled. In his Autobiography, Calder recalled:

When this show was over, I rolled them up again, all four of them, in the same bale and left them in the warehouse of my friend Maurice Lefebvre Foinet. Thus Spring and Romulus and Remus stayed there from 1929 to 1964—for thirty-five years! When we undid them the next time, they had all the freshness of youth—of my youth.[25]

By the time the Salon closed Calder had arranged to show his work at the Galérie Billiet. To secure the gallery he had to put up some of his own money, but his friend, the artist Jules Pascin—a well-known figure in the cafés of Montparnasse—contributed a humorous preface for the catalogue, and with the sale of a few things, Calder had a strong forward momentum and was already moving on from the ideas he first tackled in Romulus and Remus and Spring.

Calder’s wire sculpture continued to develop in its depiction of form, particularly in the minimization of material. In preparation for a later retrospective, Calder reviewed a roughly chronological list of various categories of his work and between “Wire sculptures” and his first abstract constructions, “Early stabiles, 1931,” the artist inserted, “What can be done with one piece of wire,” a phrase that well describes his next phase of innovation.[26]

Calder moved away from the dense coils of wire, as seen in Hercules’ pelvis and legs, and towards the simple, rhythmic lines of Acrobat. Also created in 1929 was the work Circus Scene. In Circus Scene the airborne acrobat to the left is represented by just two minimally curved wires. He is defined by his motion rather than any precise physical aspect of his body. In this work, one can observe Calder’s reliance on wire as a gesture, an expressive line, rather than a means of literal representation.

Calder continued to make wire sculpture until the fall of 1930, when he became an abstract artist. The story of Calder’s transformation is a familiar one. One day in October of 1930 he visited Piet Mondrian’s studio and was so impressed by the studio environment—colored rectangles of paper arranged on a white wall for Mondrian’s compositional experiments—that Calder suggested, “it would be fun to make these rectangles oscillate.” Mondrian replied that his painting was “already very fast.”[27] The experience stuck with Calder and he began work on a series of abstract paintings. “But wire, or something to twist, or tear, or bend, is an easier medium for me to think in,” wrote Calder and he began composing abstract sculptures out of wire and wood.[28] Some of these works had articulation and could perform one or two simple movements. By 1932, he started to engage the surrounding space by creating carefully balanced arrangements of abstract elements that moved when pushed. He suspended his abstract constructions from the ceiling or perched mobile elements atop a static base.

The experience in Mondrian’s studio was an awakening to a vocabulary for which Calder was already developing his own syntax. Calder’s progression to the mobile began much earlier and included Spring, Romulus and Remus, and Hercules and Lion. In these works he developed new sculptural and spatial possibilities for the medium of wire. The activation of empty space through suggestive volumes—a theme Calder would return to for the rest of his life—took on a grand character for the first time in these synthetic statues.[29]

Palazzo delle Esposizioni, Rome. Calder: Sculptor of Air. 23 October 2009–14 February 2010.

Solo ExhibitionHauser & Wirth, Los Angeles. Calder: Nonspace. Exhibition catalogue. 2019.

Andrew Berardini, The Cosmic Mathematics of Alexander Calder

Solo Exhibition CatalogueAlmine Rech Gallery, New York. Calder and Picasso. Exhibition catalogue. 2016.

Robert Slifkin, The Mobile Line

Susan Braeuer Dam, Liberating Lines

Jordana Mendelson, Picasso, Miró, and Calder at the 1937 Spanish Pavilion in Paris

Group Exhibition Catalogue“Calder in France.” Cahiers d’Art, no. 1 (2015). Edited by Alexander S. C. Rower.

Susan Braeuer Dam, Calder in France

Robert Melvin Rubin, An Architecture of Making: Saché and Roxbury

Agnès Varda in conversation with Joan Simon

Magazine, MonographMuseo Jumex, Mexico City. Calder: Discipline of the Dance. Exhibition catalogue. 2015.

Alexander S. C. Rower, Calder: Discipline of the Dance

Solo Exhibition Catalogue