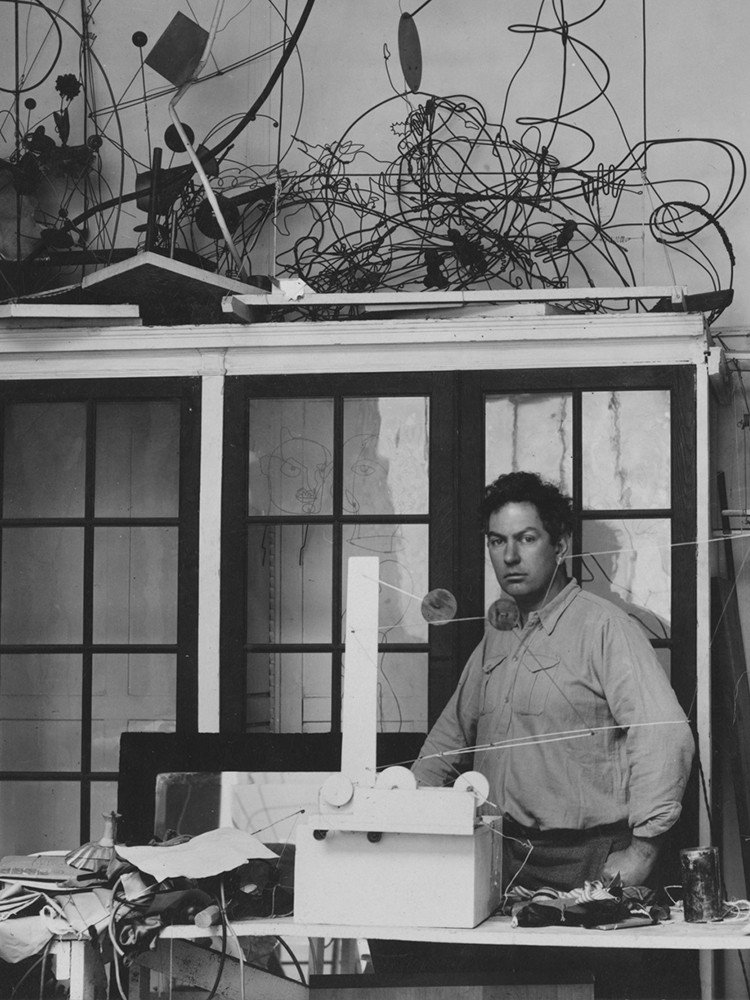

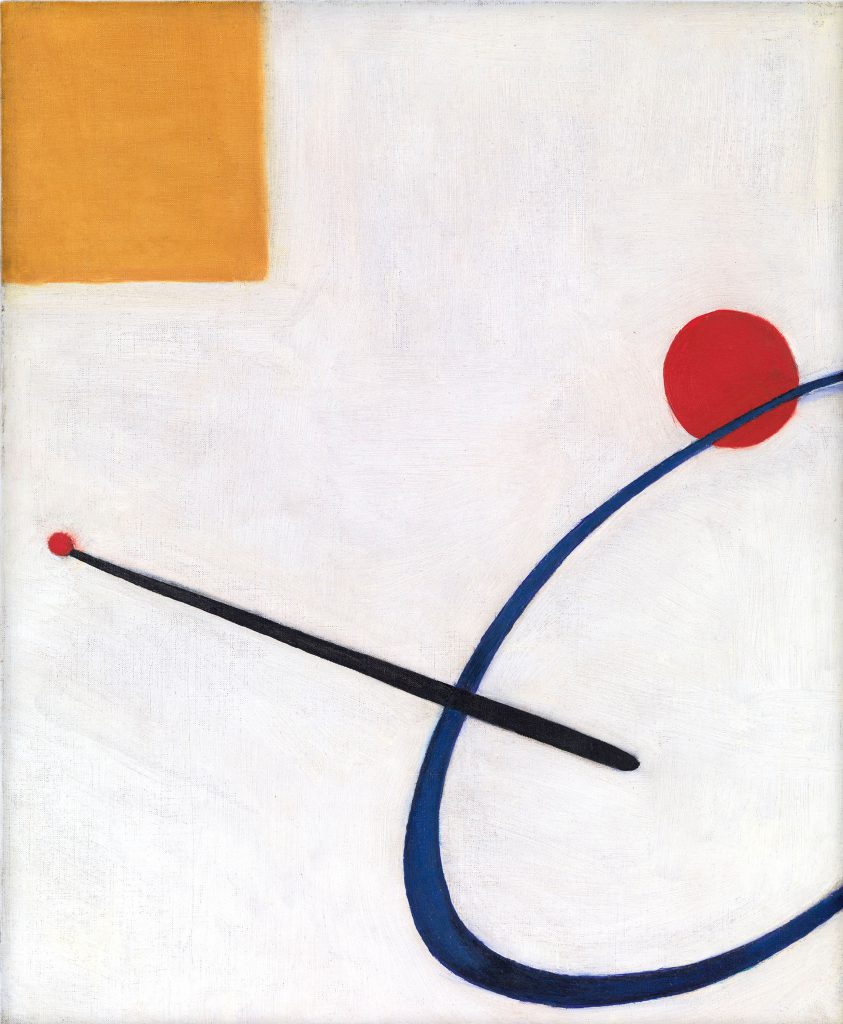

Following a visit in October of 1930 to Mondrian’s studio, where he was impressed by the environment and actuation of space, Calder made his first wholly abstract compositions and developed the kinetic sculpture now known as the mobile. Coined for these works by Marcel Duchamp in 1931, the word “mobile” refers to both “motion” and “motive” in French. Some of his earliest mobiles moved by motors, although these mechanics were virtually abandoned as Calder transitioned to mobiles that respond to air currents, light, humidity, and human interaction. He also created stationary abstract works that Jean Arp dubbed “stabiles.” The first of Calder’s outdoor works were made during this era as well.

Accompanied by another American artist, William “Binks” Einstein, Calder visits Mondrian’s studio at 26 rue du Départ. Already familiar with Mondrian’s geometric abstractions, Calder is deeply impressed by the studio environment.

It was a very exciting room. Light came in from the left and from the right, and on the solid wall between the windows there were experimental stunts with colored rectangles of cardboard tacked on. Even the victrola, which had been some muddy color, was painted red. I suggested to Mondrian that perhaps it would be fun to make these rectangles oscillate. And he, with a very serious countenance, said: “No, it is not necessary, my painting is already very fast.” This one visit gave me a shock that started things. Though I had heard the word “modern” before, I did not consciously know or feel the term “abstract.” So now, at thirty-two, I wanted to paint and work in the abstract. And for two weeks or so, I painted very modest abstractions. At the end of this, I reverted to plastic work which was still abstract.

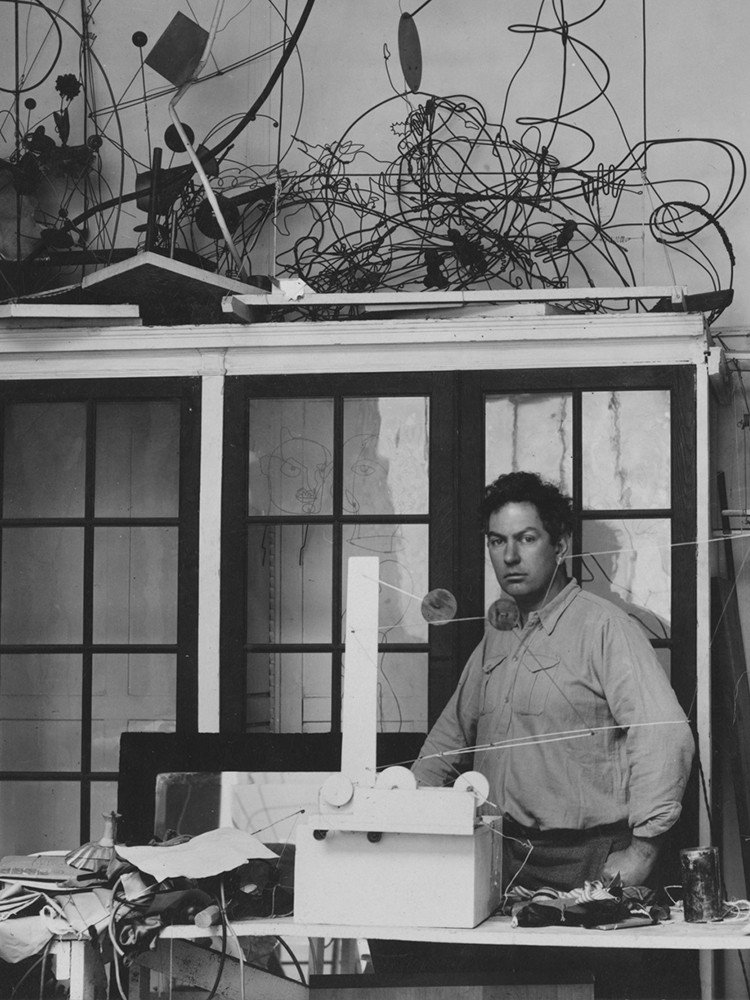

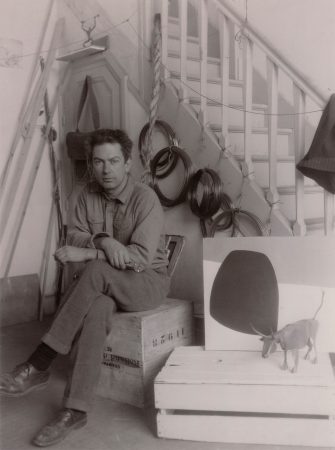

Thérèse Bonney photographs Calder in his studio at 7 Villa Brune.

Louisa James decides to marry Calder.

I have just come home from a polo game with a not particularly entrancing young man, and I have decided that I am sick to death of going out with one person and another that don’t interest me. I am sick of it chiefly because the only person that amuses me and has amused me for the last year and a half, is Sandy. The only thing to do to my mind is to make it permanent and get married, and the sooner the better . . . To me Sandy is a real person which seems to be a rare thing. He appreciates and enjoys the things in life that most people haven’t the sense to notice. He has ideals, ambition, and plenty of common sense, with great ability. He has tremendous originality, imagination, and humor which appeal to me very much and which make life colorful and worthwhile. He enjoys working and works hard, and thus ends the summary of his character.

Calder makes a gold ring to present to Louisa James.

I had known a little jeweler in Paris, Bucci, and he had helped me make a gold ring—forerunner of an array of family jewelry—with a spiral on top and a helix for the finger. I thought this would do for a wedding ring. But Louisa merely called this one her “engagement ring” and we had to go to Waltham, near by, and purchase a wedding ring for two dollars.

Calder exhibits four wood sculptures, including Cow, in “Painting and Sculpture by Living Americans” at the Museum of Modern Art, New York.

Calder and Louisa James are married.

The reverend who married us apologized for having missed the circus the night before. So I said: “But you are here for the circus, today.”

The Abstraction-Création group is founded; members include Jean Arp, Robert Delaunay, William “Binks” Einstein, Jean Hélion, Mondrian, and Anton Pevsner.

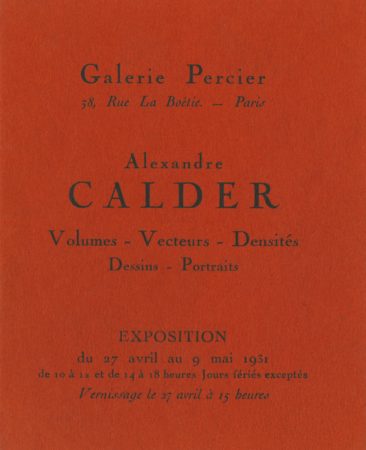

Calder’s abstract work is presented for the first time in the exhibition “Alexandre Calder: Volumes–Vecteurs–Densités / Dessins–Portraits,” at Galerie Percier, Paris. Léger writes the introduction to the catalogue.

Fernand Léger, Introduction

Galerie Percier, Paris. Alexandre Calder: Volumes–Vecteurs–Densités / Dessins–Portraits. Exhibition catalogue. 1931.

Eric Satie illustrated by Read more

Calder Read more

Why not? Read more

“It’s serious without seeming to be.” Read more

Neoplastician from the start, he believed in the absolute of two colored rectangles…. Read more

His need for fantasy broke the connection; he started to “play” with his materials: wood, plaster, iron wire, especially iron wire…. a time both picturesque and spirited…. Read more

….A reaction; the wire stretches, becomes rigid, geometrical—pure plastic—it is the present era—an anti-Romantic impulse dominated by the problem of equilibrium. Read more

Looking at these new works—transparent, objective, exact—I think of Satie, Mondrian, Marcel Duchamp, Brancusi, Arp—those unchallenged masters of unexpressed and silent beauty. Calder is of the same line. Read more

He is 100% American. Read more

Satie and Duchamp are 100% French. Read more

And yet, we meet? Read more

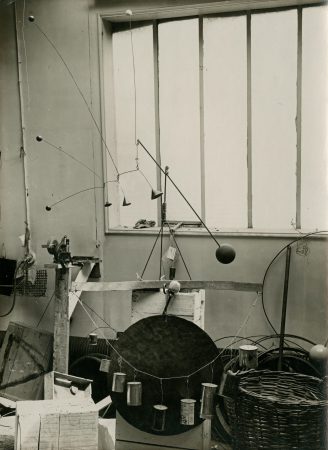

The Calders move into a three-story house at 14 rue de la Colonie. Calder makes the top floor of his house his studio.

Louisa buys a dog, a small Briard mix. She and Calder name him Feathers because of his wispy hair.

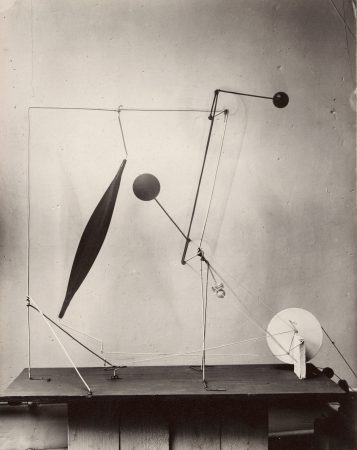

Using cranks and small electric motors, Calder concentrates on making mechanized abstract sculptures.

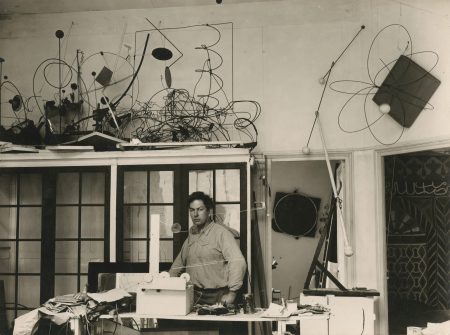

Marcel Duchamp visits the studio at 14 rue de la Colonie again and sees Calder’s latest works.

There was one motor-driven thing, with three elements. The thing had just been painted and was not quite dry yet. Marcel said, “Do you mind?” When he put his hands on it, the object seemed to please him, so he arranged for me to show in Marie Cuttoli’s Galerie Vignon, close to the Madeleine. I asked him what sort of a name I could give these things and he at once produced “Mobile.” In addition to something that moves, in French it also means motive. Duchamp also suggested that on my invitation card I make a drawing of the motor-driven object and print: CALDER/SES MOBILES.

Calder selects a sculpture from among the works exhibited at Galerie Percier and donates it to the recently founded Miejskie Muzeum Historji i Sztuki (Muzeum Sztuki w Lodzi), in Lodz, Poland. The work is later lost during World War II. (Calder 1966, 118)

How can art be realized? Read more

Out of volumes, motion, spaces bounded by the great space, the universe. Read more

Out of different masses, light, heavy, middling—indicated by variations of size or color—directional lines—vectors which represent speeds, velocities, accelerations, forces, etc … —these directions making between them meaningful angles, and senses, together defining one big conclusion or many. Read more

Spaces, volumes, suggested by the smallest means in contrast to their mass, or even including them, juxtaposed, pierced by vectors, crossed by speeds. Read more

Nothing at all of this is fixed. Read more

Each element able to move, to stir, to oscillate, to come and go in its relationships with the other elements in its universe. Read more

It must not be just a “fleeting” moment, but a physical bond between the varying events in life. Read more

Not extractions, Read more

But abstractions Read more

Abstractions that are like nothing in life except in their manner of reacting. Read more

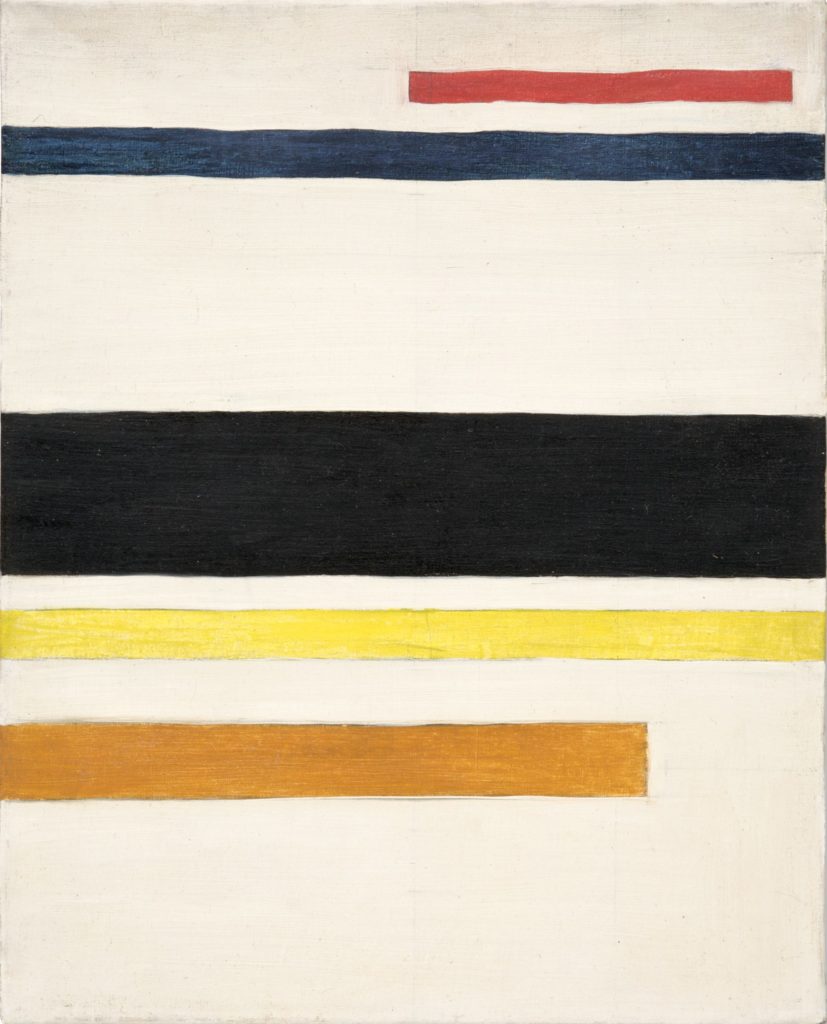

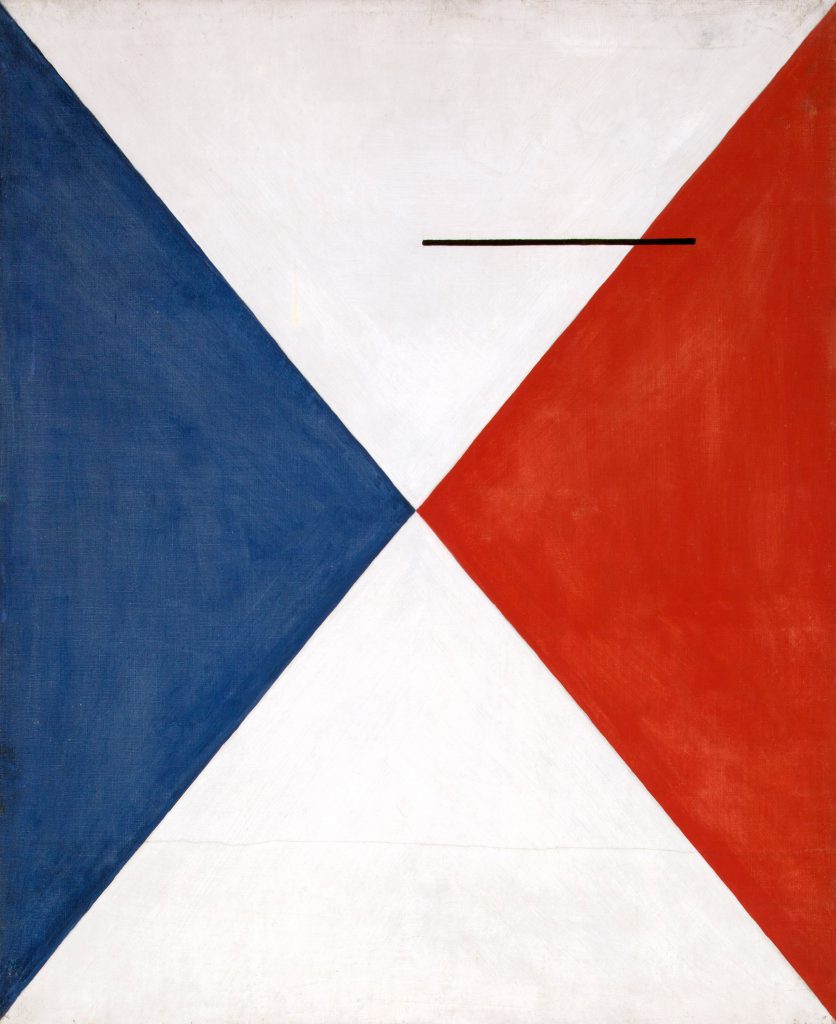

Calder makes Cadre rouge, among the first in a series of “frames” and “panels” that consist of moving abstract forms set in front of colored plywood panels or within boxlike frames. The works relate to the idea of three-dimensional paintings in motion that Calder proposed to Mondrian during his 1930 visit.

“Calder: ses mobiles” is held at Galerie Vignon, Paris.

In response to Duchamp’s term “mobile,” Arp asks sarcastically, Well, what were those things you did last year [for Percier’s]—stabiles? Calder adopts “stabile” to refer to his static works.

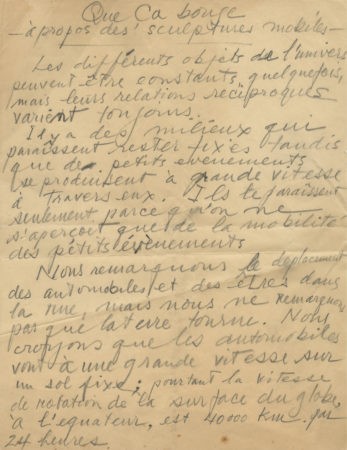

Calder, Alexander. “Que ça bouge—À propos des sculptures mobiles.” Manuscript, 8 March 1932. Calder Foundation, New York.

The various objects of the universe may be constant, at times, but their reciprocal relationships always vary. Read more

There are environments that appear to remain fixed whilst there are small occurrences that take place at great speed across them. They appear so only because one sees nothing but the mobility of the small occurrences. Read more

We notice the movement of automobiles and beings in the street, but we do not notice that the earth turns. We believe that automobiles go at a great speed on a fixed ground; yet the speed of the earth’s rotation at the equator is 40,000 km every 24 hours. Read more

As truly serious art must follow the greater laws, and not only appearances, I try to put all the elements in motion in my mobile sculptures. Read more

It is a matter of harmonizing these movements, thus arriving at a new possibility of beauty. Read more

Before a group of reporters visiting his exhibition at Julien Levy Gallery, Calder demonstrates the motion in Two Spheres.

This has no utility and no meaning. It is simply beautiful. It has a great emotional effect if you understand it. Of course if it meant anything it would be easier to understand, but it would not be worthwhile.

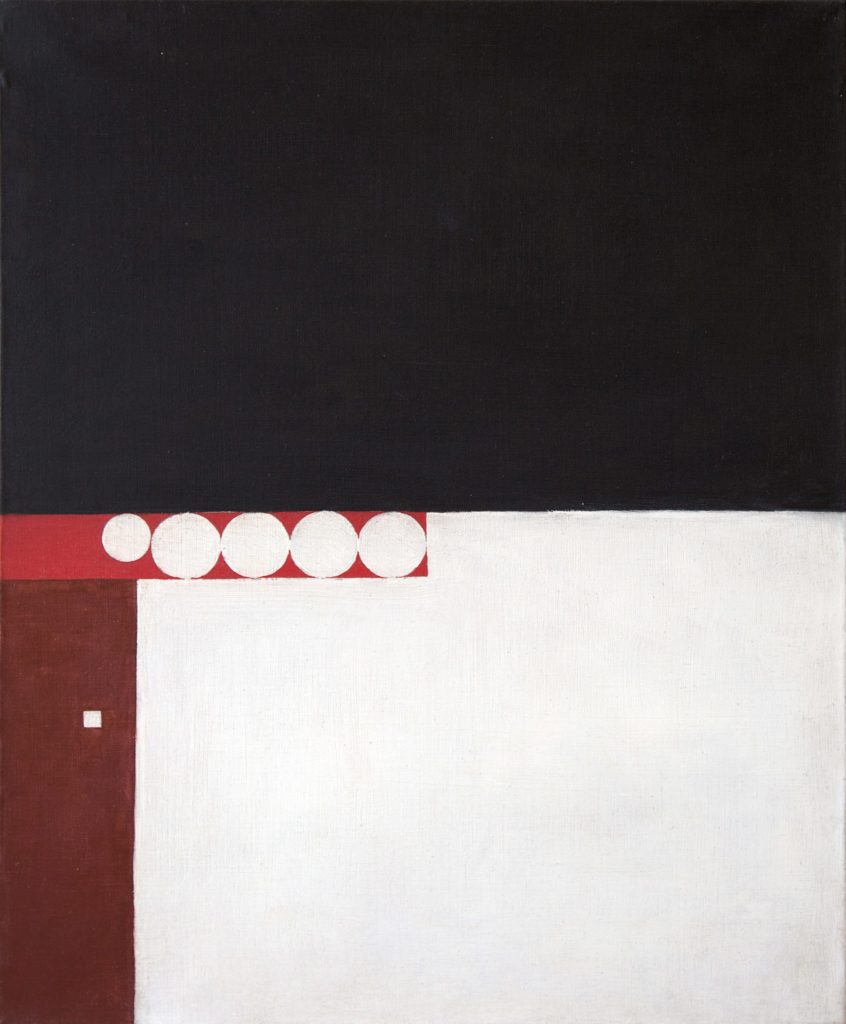

A “Mobile.” Read more

Frame: 8 centimeters, neutral red.

The 2 white balls turn very rapidly.

The black helix turns less rapidly and seems to always climb.

The iron plate turns still less quickly, the two black lines seeming always to climb.

The black pendulum, 40 centimeters in diameter, climbs by 45° on each side, passing in front of the frame, at the rate of 25 turns a minute. Read more

The Calders take a train from Paris to Madrid, where they visit the Museo del Prado.

Jean Painlevé films both Calder’s mechanized objects and the artist activating his works outside his studio at 14 rue de la Colonie. It is the earliest motion picture footage of mobiles in motion.

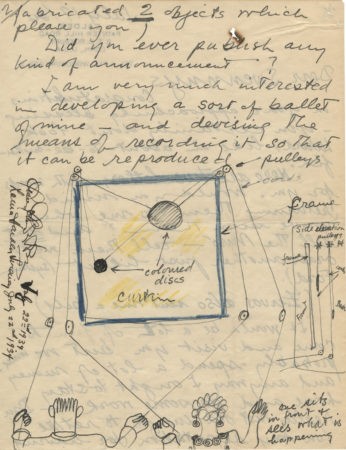

Calder constructs an interactive “performance” sculpture.

I had a small ballet-object, built on a table with pulleys at the top of a frame. It was possible to move coloured discs across the rectangle, or fluttering pennants, or cones; to make them dance, or even have battles between them. Some of them had large, simple, majestic movements; others were small and agitated.

Galerie Pierre Colle, Paris, exhibits “Présentation des oeuvres récentes de Calder,” including an untitled standing mobile and Small Sphere and Heavy Sphere. Reviewing the exhibition, Paul Recht writes,

The liberty of some of the ensembles is absolutely disconcerting: we see two balls, one little and one big, in turn fixed to wires of very different lengths that are themselves fixed to the two extremities of a balancing arm hung above the ground. The big ball is animated by a pendular and rotary movement; it leads the little one on unexpected evolutions that multiply by impact upon surrounding objects. They are extraordinary visual variations on the theme of calamity, by the means of gravity and centrifugal force.

Miró presents the Calders with a large blue painting as a going-away present. Calder gives him “a sort of mechanized volcano, made of ebony.”

The Calders give up their house in Paris and return to New York on the SS Manhattan in the company of Hélion.

There were so many articles in the European press about war preparations that we thought we had better head for home.

Upon arriving in the States, the Calders visit Louisa’s parents in Concord, Massachusetts.

There, we bought a secondhand 1930 LaSalle touring car. It had a cloth top, removable, and could seat nine, with broad seats front and rear and jump seats as well. It was in good shape; I kept it a long time and enjoyed it. You got plenty of air in this vehicle. And often I took my wares to open a show in New York in it. (All in all, I kept this LaSalle for over seventeen years!)

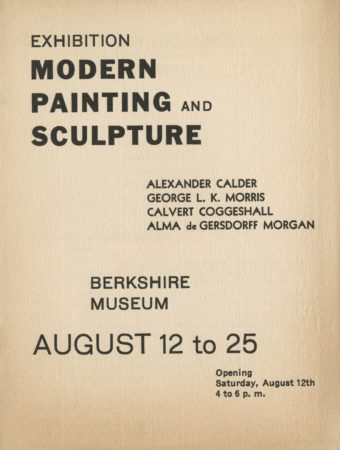

Among the fifteen Calder sculptures on display in “Modern Painting and Sculpture” at the Berkshire Museum, Pittsfield, Massachusetts, are Dancing Torpedo Shape, Nymph, and one of the wire Josephine Bakers. Calder writes a statement for the catalogue.

Alexander Calder, Statement

Berkshire Museum, Pittsfield, Massachusetts. Modern Painting and Sculpture: Alexander Calder, George L.K. Morris, Calvert Coggeshall, Alma de Gersdorff Morgan. Exhibition catalogue. 1933.

Why not plastic forms in motion? Not a simple translatory or rotary motion but several motions of different types, speeds and amplitudes composing to make a resultant whole. Just as one can compose colors, or forms, so one can compose motions. Read more

The Calders visit a real-estate agency in Danbury, Connecticut. After viewing several properties, they discover a dilapidated eighteenth-century farmhouse in Roxbury, Connecticut; both Louisa and Calder claim to have been the first to exclaim, “That’s it!”

The Calders stay with de Creeft in New Milford, Connecticut, during the Roxbury farmhouse renovation.

By taking out a partition between a small room and the biggest one to the south—it had been a kitchen and had a sink which we removed—we turned these two rooms, exposed east and south, with a door going directly outside, into a nice sunny living room. We made the kitchen in the north corner of the house; we like the sun but we wanted the living room to benefit from it most.

Calder makes Objects Oscillating Within a Cube (maquette) for the American composer Harrison Kerr.

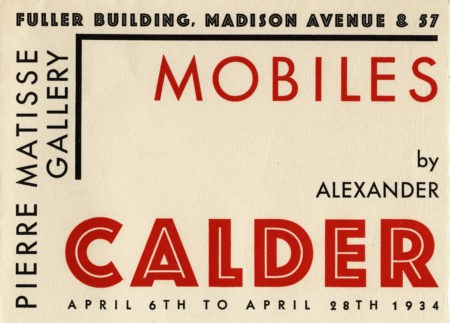

“Mobiles by Alexander Calder” is presented at the Pierre Matisse Gallery, New York. Sweeney writes the preface for the catalogue.

James Johnson Sweeney, Mobiles by Alexander Calder

Pierre Matisse Gallery, New York. Mobiles by Alexander Calder. Exhibition catalogue. 1934.

The evolution of Calder’s work epitomizes the evolution of plastic art in the present century. Out of a tradition of naturalistic representation, it has worked by a simplification of expressional means to a plastic concept which leans on the shapes of the natural world only as a source from which to abstract the elements of form. Read more

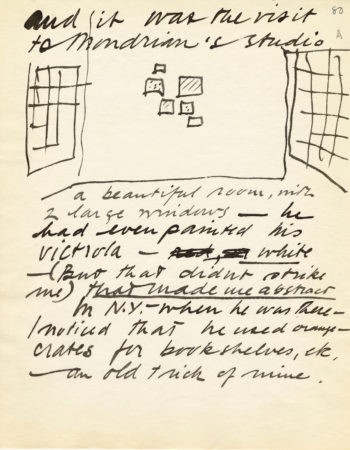

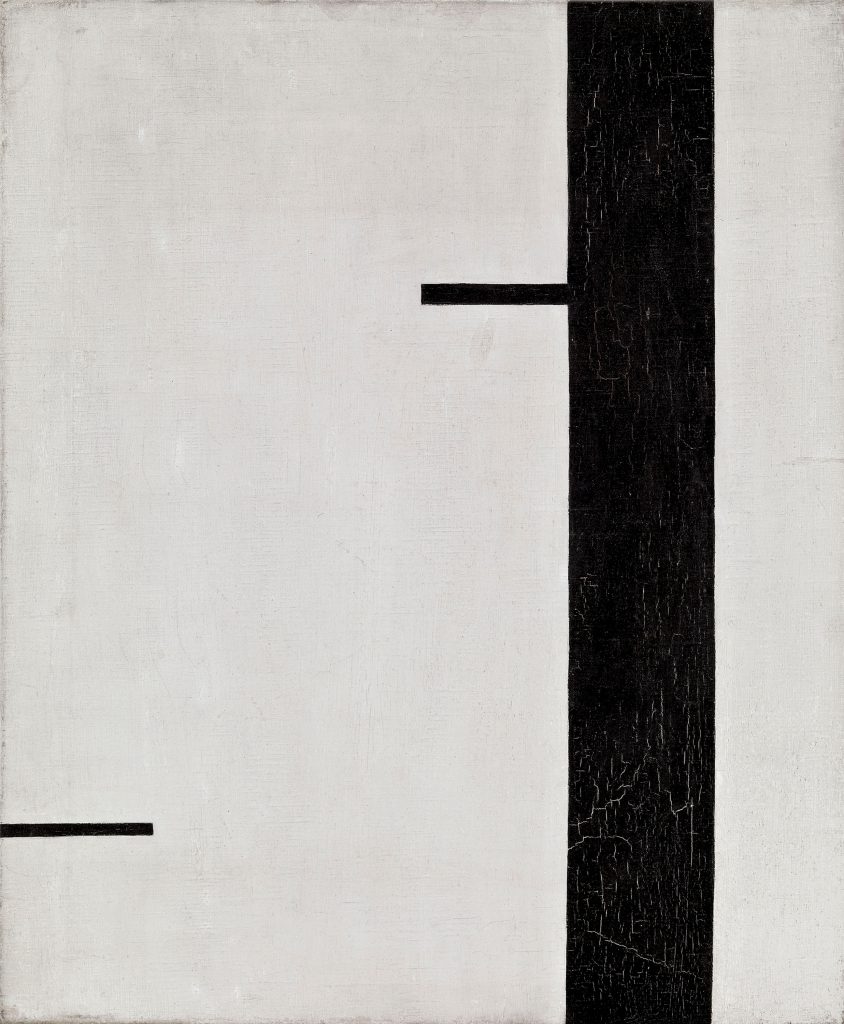

In Roxbury, Calder creates Black Frame.

One I like very much myself is a black wooden frame, with sheets of metal within it, warped into various planes, and having certain moving elements, which are the brilliant spots in an otherwise sombre setting.

In Roxbury, Calder works prolifically on “panels” and “frames.”

I am very much interested in developing a sort of ballet of mine—and devising the means of recording it so that it can be reproduced. The backgrounds can be changed—and the lighting varied. The discs can move anywhere within the limits of the frame, at any speed. Each disc

and its supporting pulleys is in a separate vertical plane parallel to the frame. The number of discs can be increased indefinitely—depending on the necessary clearances. In addition to discs there are coloured pennants (of cloth), with weights on them, which fly at high speed—and various solid objects, bits of hose, springs, etc. […] I had this in Paris the spring of 1933 and showed it to Massine— along with many other things, and it’s what I wanted to do for the Ballets Russes. Of course the real problem to magnify the movement to a full sized proscenium—but I can see various ways of obtaining it.

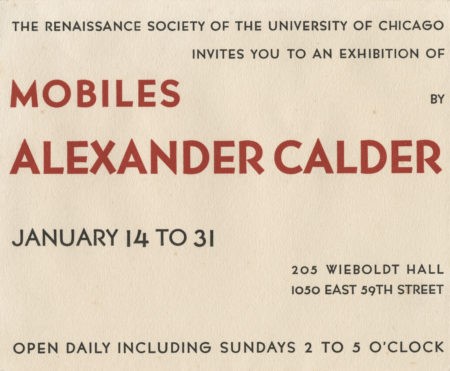

“Mobiles by Alexander Calder” is held at the Renaissance Society at the University of Chicago; Sweeney writes the preface for the catalogue. On the 16th and 19th of January, Calder gives performances of Cirque Calder in the University of Chicago’s Wieboldt Hall for the Renaissance

Society. He also performs at the home of Walter S. Brewster, a trustee of the Art Institute of Chicago, on 20 January.

James Johnson Sweeney, Alexander Calder’s Mobiles

The Renaissance Society at The University of Chicago. Mobiles by Alexander Calder. Exhibition catalogue. 1935.

Calder offers Sweeney a sculpture from his first show at the Pierre Matisse Gallery, for which Sweeney had written an introduction to the catalogue. Sweeney chooses Object with Red Discs; on principle, he insists that Calder accept a small sum in return for the sculpture. The

Sweeney family enjoys the object immensely and Sweeney’s brother, John, dubs it “Calderberry-bush.”

While traveling home from Chicago, Calder stops in Rochester, New York, to see Charlotte Whitney Allen, who commissions a standing mobile for her garden, which had been designed by landscape architect Fletcher Steele.

The Calders’ first daughter, Sandra, is born, on Miró’s birthday.

Calder constructs mobile sets for Martha Graham’s dance Panorama. On 5–6 August, Calder and Louisa visit Graham in Bennington, Vermont, to preview Panorama before its premiere at the Vermont State Armory, Bennington, on 14 August.

The Calders spend the winter in an apartment at 244 East Eighty-sixth Street and Second Avenue, New York. Calder rents a small store and converts it into a studio.

Calder again collaborates with Graham, making a group of six mobiles—”visual preludes”—for her dance Horizons.

Julien Levy’s Surrealism, the first English text on the subject, is published in New York. Levy writes:

It is impossible accurately to estimate the relative importance of the younger surrealists, until aided by the perspective of time. Outstanding among the newcomers seem to be Gisèle Prassinos, Richard Oelze, Hans Bellmer, Leonor Fini, Alexander Calder, and Joseph Cornell . . . Calder is sometimes surrealist and sometimes abstractionist. It is to be hoped that he may soon choose in which direction he will throw the weight of his talents.

First Hartford Music Festival, Wadsworth Atheneum, presents Erik Satie’s symphonic drama Socrate. Virgil Thomson and A. Everett “Chick” Austin, Jr., have commissioned Calder to create the mobile decor for the performance. As the singers stand still at either end of the

stage, Calder’s simple geometric objects in space enact a series of movements. Later that night the festival continues with Paper Ball: Le Cirque des Chiffoniers, designed by Pavel Tchelitchew and featuring thirteen processions of paper costumes created especially for the event. For Soby’s procession, Calder contributes A Nightmare Side Show, a suite of animal costumes designed to wear over evening clothes.

“Cubism and Abstract Art” is presented by Alfred H. Barr, Jr., at the Museum of Modern Art, New York. Calder is represented by three works: Objet Volant, a large mobile commissioned to hang on the flagpole outside the museum, announcing the show; A Universe; and a mobile.

Roland Penrose’s “International Surrealist Exhibition” at his New Burlington Galleries, London, includes two sculptures by Calder, among them Requin et Baleine. André Breton writes the preface to the catalogue.

Calder’s Praying Mantis and Object with Yellow Background are included in the exhibition “Fantastic Art, Dada, Surrealism,” organized by the Museum of Modern Art, New York.

In 1937, Calder completed Devil Fish, his first stabile enlarged from a model. He received two important commissions: Mercury Fountain (1937) and Lobster Trap and Fish Tail (1939). His first retrospective was held in 1938 at the George Walter Vincent Smith Gallery in Springfield, Massachusetts, followed by another in 1943 at the Museum of Modern Art in New York.