In 1937, Calder completed Devil Fish, his first stabile enlarged from a model. He received two important commissions: Mercury Fountain for the Spanish Pavilion at the 1937 Paris World’s Fair and Lobster Trap and Fish Tail for the main stairwell of the new Museum of Modern Art building in New York in 1939. His first retrospective was held in 1938 at the George Walter Vincent Smith Gallery in Springfield, Massachusetts. Another retrospective followed in 1943 at the Museum of Modern Art in New York, curated by James Johnson Sweeney and Marcel Duchamp. Calder was the youngest artist ever to whom the museum had dedicated a full-career survey, which was so popular that it was extended into 1944.

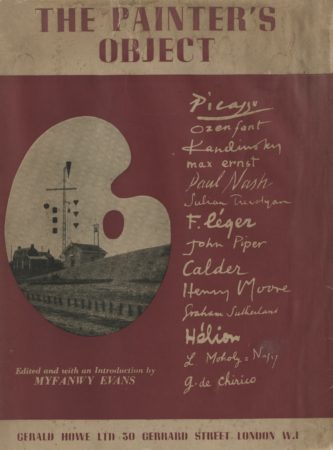

Calder, Alexander. “Mobiles.” In The Painter’s Object, edited by Myfanwy Evans. London: Gerald Howe, 1937.

I have made a number of things for the open air: all of them react to the wind, and are like a sailing vessel in that they react best to one kind of breeze. It is impossible to make a thing work with every kind of wind. Read more

Calder’s first large-scale bolted stabiles, Devil Fish and Big Bird, are on view in “Calder: Stabiles & Mobiles” at the Pierre Matisse Gallery, New York.

Calder and Miró visit the Spanish pavilion under construction at the 1937 World’s Fair site in Paris. Calder meets the pavilion’s architects, Josep Lluís Sert and Luis Lacasa. Sert eventually commissions Calder to make Mercury Fountain for the Spanish pavilion. Mined in Almadén in

Spain, the mercury symbolizes Republican resistance to fascism.

The Calders rent a house in Varengeville at 50 le Clos du Timbre, where Calder uses the garage as his studio. Jean Hélion, who had been to London a few years before, had put me in contact with John and Myfanwy Piper and Ben Nicholson and Barbara Hepworth, and we lost no

time in inviting the Pipers and the Nicholsons, separately, of course. Other visitors to the house include Georges Braque, Pierre Loeb, Miró, the Nelsons, and cultural theorist Herbert Read.

The Mayor Gallery, London, exhibits “Calder: Mobiles and Stabiles.”

A review of the exhibition at the Mayor Gallery notes,

Calder’s jewelry is as pretty as his mobiles—some of it too is “mobile”—and often more seriously lovely. If the lady of fashion has the wit to see it, she may find that pieces of human ingenuity make rather more distinguished ornaments than Cartier’s portable currency.

To give the whole design more height, and to increase its mobility I hung a rod vertically from a ring at its middle, whose lower end widened out into a plate of irregular form, at the center of the basin, so that the jet of mercury leaving the chute would strike the plate causing it and the rod to sway about. From the upper end of the rod I hung another, lighter rod, in similar fashion, at whose lower extremity was a circular disc painted red, and from whose upper end was flaunted the name of the mines, Almaden, in brass wire. Read more

Calder begins construction of a large studio on the old dairy barn foundations in Roxbury. Soon after, he converts his icehouse studio into a living space that comes to be known as the “Big Room.”

Calder’s first retrospective, “Calder Mobiles,” is presented by the George Walter Vincent Smith Gallery, Springfield, Massachusetts. Sweeney writes a foreword to the catalogue. Aalto, Léger, architectural historian Siegfried Giedion, and art patron Katherine S. Dreier attend the

opening. Sixty-one pieces of jewelry are included in the exhibition.

Calder is commissioned by the Museum of Modern Art, New York, to make Lobster Trap and Fish Tail, a mobile he installs in the principal stairwell of the museum’s new building on West Fifty-third Street.

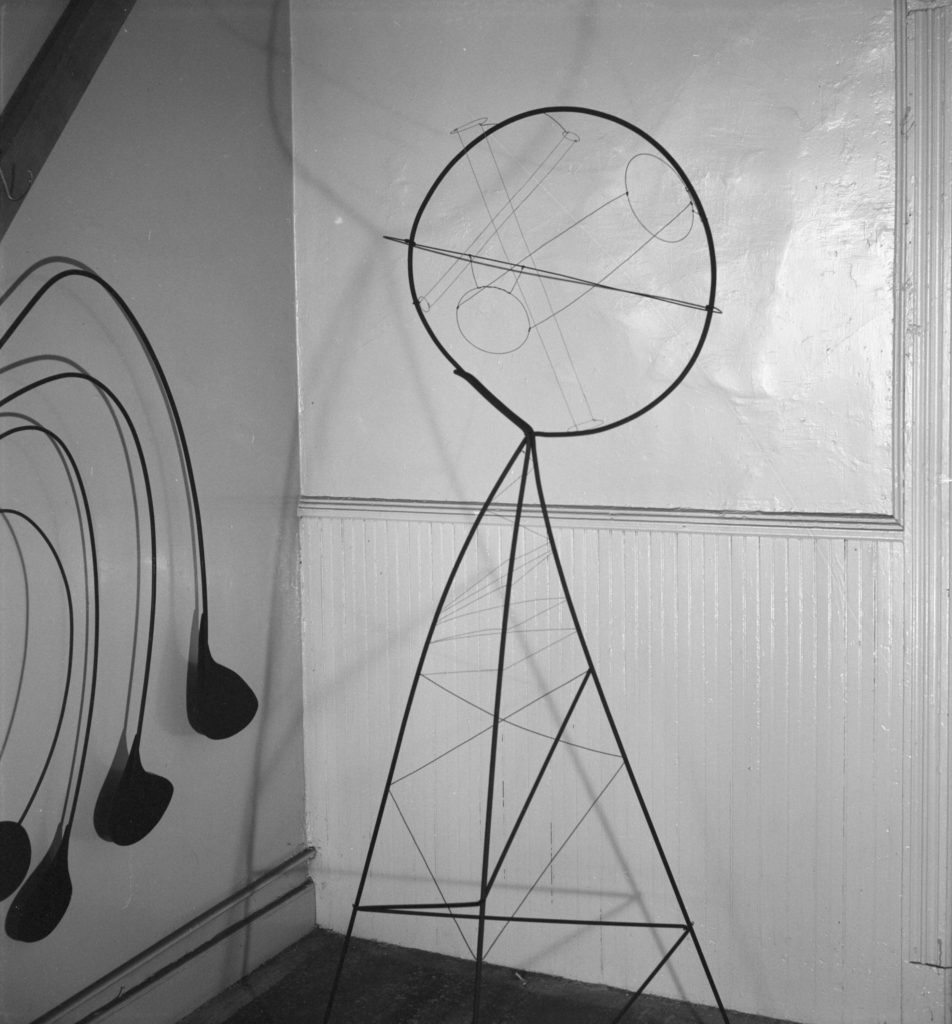

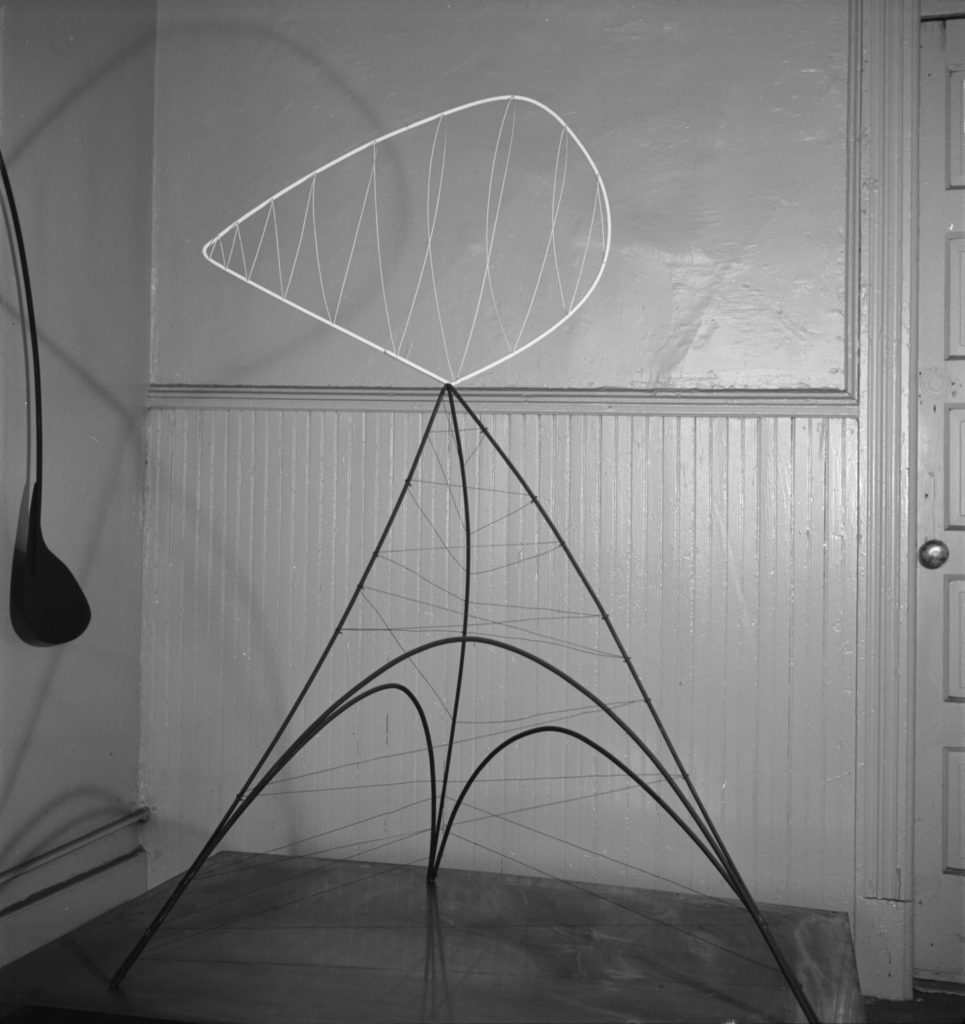

Calder is invited to make sculptures for an African habitat designed by Oscar Nitzschke for the Bronx Zoo. Calder conceives of treelike sculptures to be made in steel so they can withstand the abuse of the wild animals. Although the habitat is never realized, Calder creates five

models for the project: Sphere Pierced by Cylinders, Hollow Egg, Four Leaves and Three Petals, Leaves and Tripod, and The Hairpins.

Calder creates six maquettes to complement architect Percival Goodman’s design for the Smithsonian Gallery of Art Architectural Competition, sponsored by the Smithsonian Gallery of Art Commission. Goodman is awarded second place to Eliel Saarinen, and the

project goes unrealized.

Calder is commissioned by Wallace K. Harrison and André Fouilhoux, architects of Consolidated Edison’s pavilion at the 1939 New York World’s Fair, to design a “water ballet” for the building’s fountain. Although water jets are installed around the pavilion, this ballet is never

executed.

It occupies a space about 100 feet wide and 30 feet deep. At each end there is a nozzle which swings in a vertical plane between two positions, one almost vertical, the other more or less horizontal, pointing inward toward the centre. These two jets are used for the opening movement of the ballet. Read more

Sweeney, James Johnson. “Alexander Calder: Movement as a Plastic Element.” Plus, no. 2 (February 1939).

Calder in introducing actual movement into his plastic organizations has given a new emphasis to the basic rhythmic gesture. This has had the fundamental value of a primitive appeal. And, it comes with Calder’s work, at a moment when plastic expression is ripe for such a physical realization of movement. Read more

The Calders’ second daughter, Mary, is born.

Pierre Matisse Gallery, New York, presents “Calder.”

“Calder Jewelry” is presented at Willard Gallery, New York. In her press release for the show, Willard writes,

These works of art are savage and deliberate and self-confidently sophisticated . . . This is a master modern artist’s contribution to the history of fashion. For a world already in chains it is superb stuff.

Harrison commissions Calder to make a mobile for the Hotel Avila Ballroom, Caracas, Venezuela.

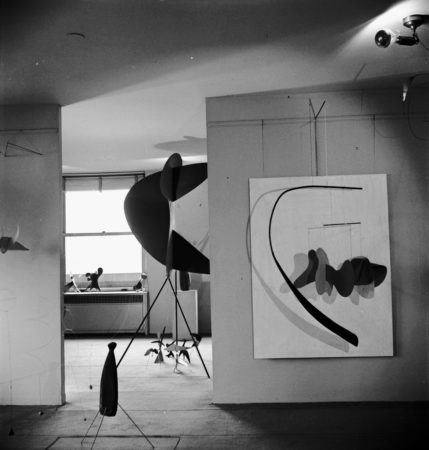

Herbert Matter photographs Calder’s Roxbury studio.

“Alexander Calder: Recent Works” is held at the Pierre Matisse Gallery, New York.

Calder performs Cirque Calder in Roxbury.

Calder is commissioned to make Red Petals for the Arts Club of Chicago.

Sculptures by Calder and paintings by Miró are exhibited at Vassar College, Poughkeepsie, New York.

Calder is classified 1-A (top eligibility) by the army, though he is never drafted. He studies industrial camouflage at New York University and applies for a commission in camouflage work with the Marine Corps: Although the army says that the painter is of little or no use in modern

camouflage, I feel that this is not so, and that the camoufleur is still a painter, but on an immense scale . . . and in a negative sense (for instead of creating, he demolishes a picture and reduces it to nil . . . ).

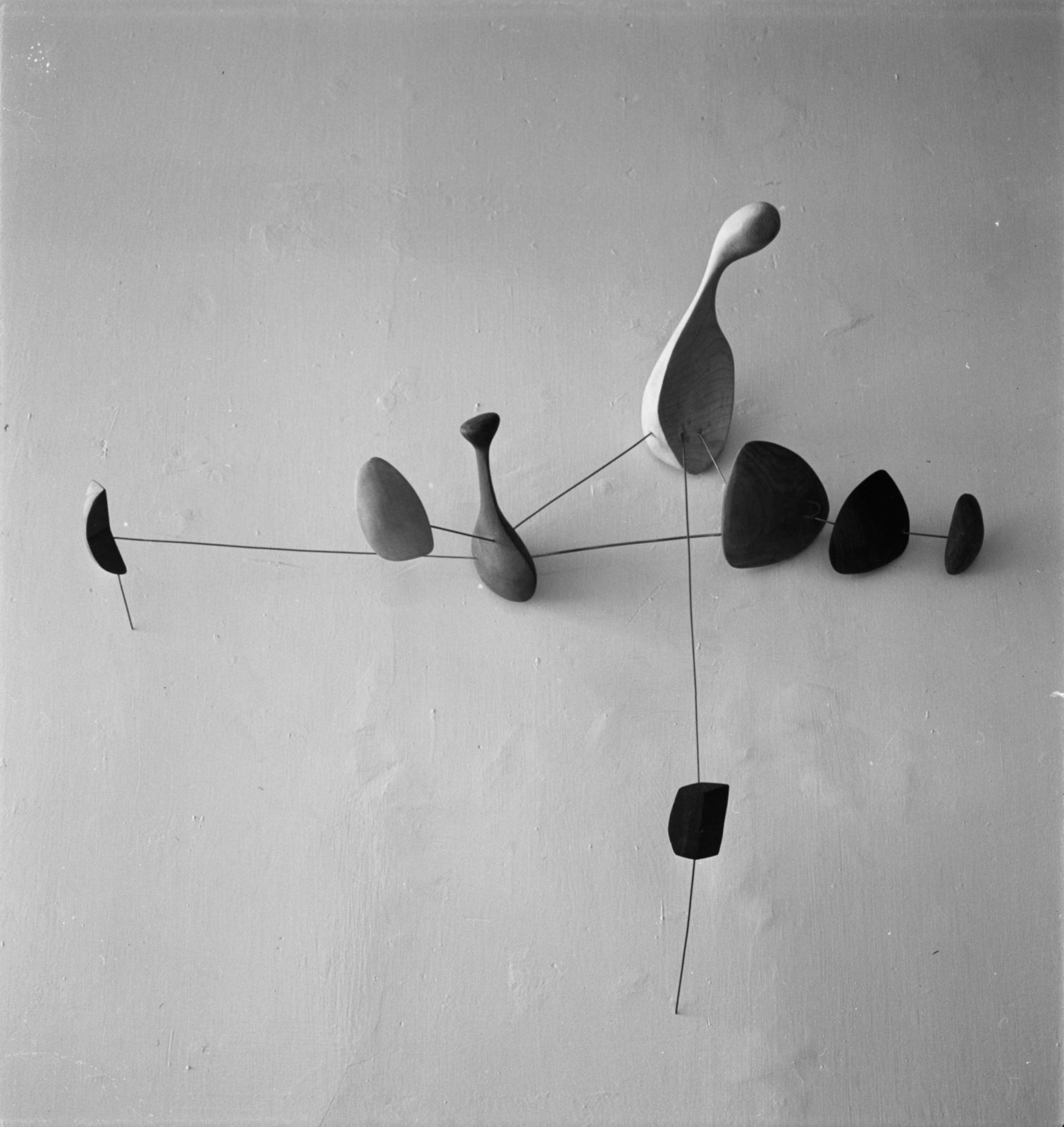

Calder works on a new open form of sculpture made of carved wood and wire. They had a suggestion of some kind of cosmic nuclear gases—which I won’t try to explain. I was interested in the extremely delicate, open composition. Sweeney and Duchamp propose the name “constellations” for

these works, seven of which will be included in the artist’s upcoming retrospective at the Museum of Modern Art, New York.

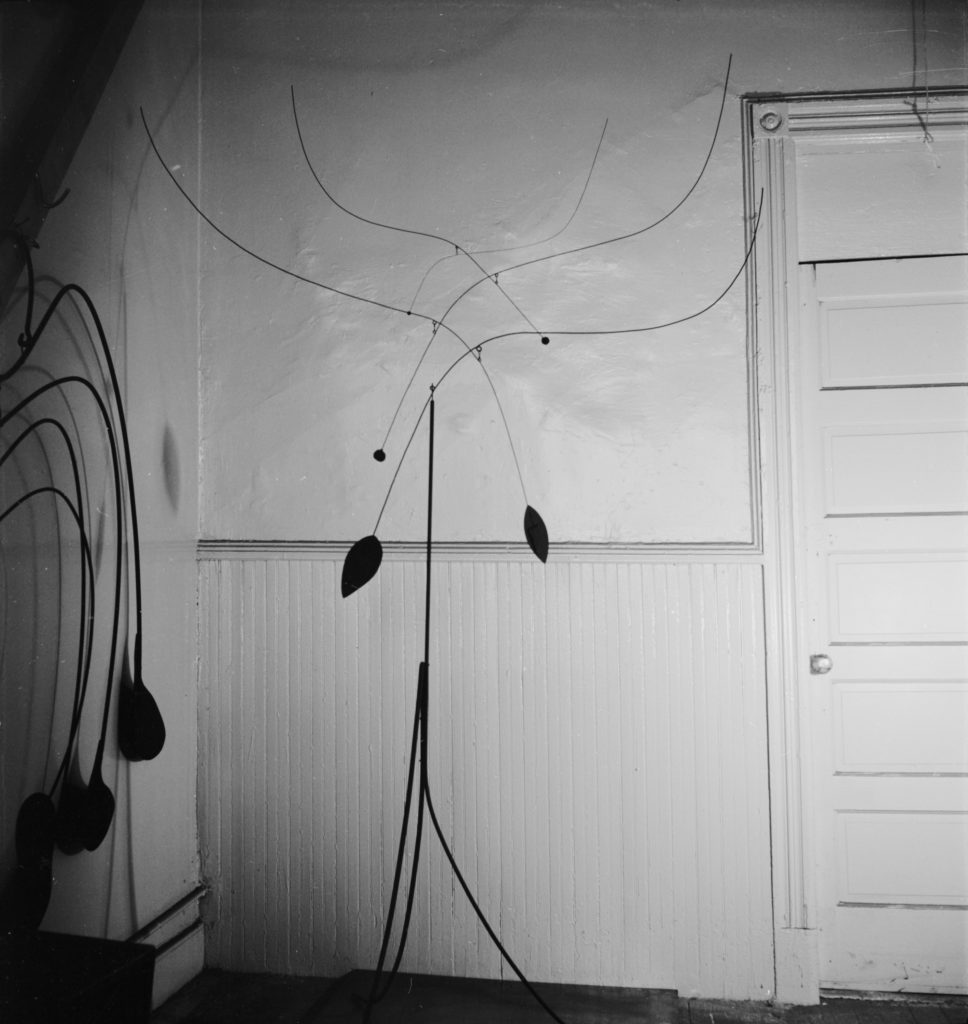

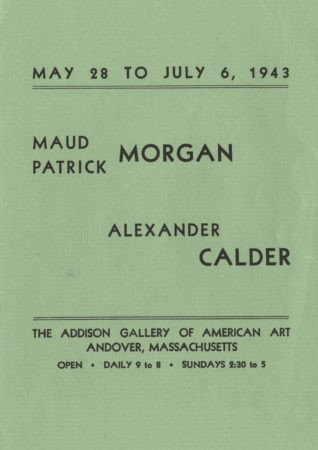

“17 Mobiles by Alexander Calder” is held at the Addison Gallery of American Art, Andover, Massachusetts. The catalogue contains a statement by Calder.

Alexander Calder, Statement

Addison Gallery of American Art, Andover, Massachusetts. 17 Mobiles by Alexander Calder. Exhibition catalogue. 1943.

At first [my] objects were static, seeking to give a sense of cosmic relationship. Then . . . I introduced flexibility, so that the relationships would be more general. From that I went to the use of motion for its contrapuntal value, as in good choreography. Read more

Calder writes to Sweeney about his forthcoming retrospective at the Museum of Modern Art, New York.

I forgot to show you this object. One swings the red (iron) ball in a small circle—this movement and the inertia of the rod and the length of thread develops a very complicated pattern of movement. The impedimenta—boxes, cymbal, bottles, cans etc. add to the complication, and also add sounds of thuds, crashes, etc.—This is a reconstruction of one I had in Paris in ’33. I will bring it down and set it up for you to see. I call it the “Small Sphere and Heavy Sphere.”

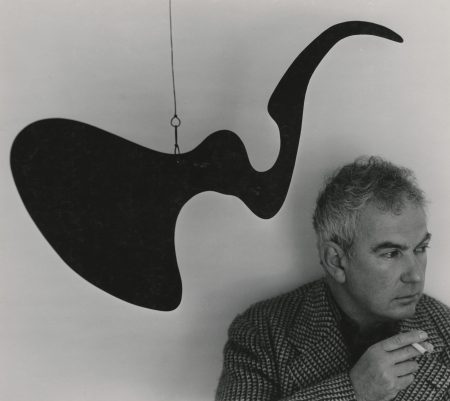

Arnold Newman photographs Calder at the Museum of Modern Art, New York.

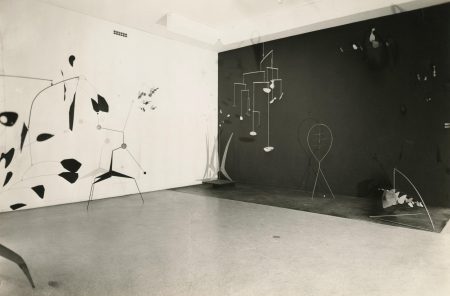

The Museum of Modern Art, New York, presents “Alexander Calder: Sculptures and Constructions,” curated by Sweeney and Duchamp. Calder writes, Simplicity of equipment and an adventurous spirit in attacking the unfamiliar or unknown are apt to result in a primitive and

vigorous art. Somehow the primitive is usually much stronger than art in which technique and flourish abound. Originally scheduled to close on 28 November 1943, the exhibition is extended to 16 January 1944 due to public demand.

Both the “Big Room” and part of the Roxbury farmhouse are destroyed by an electrical fire. Louisa tells Calder about the fire when he joins them on 7 December.

What was destroyed was the icehouse, my original workshop, where the electricity had probably shorted, and the woodshed and a corner of the bathroom. The toilet, which was of china, had exploded. It must have been a dreary business for Louisa and Malcolm to drag all they could save to my new shop—this seemed to fill it completely when I got there. Gone were the unencumbered spaces.

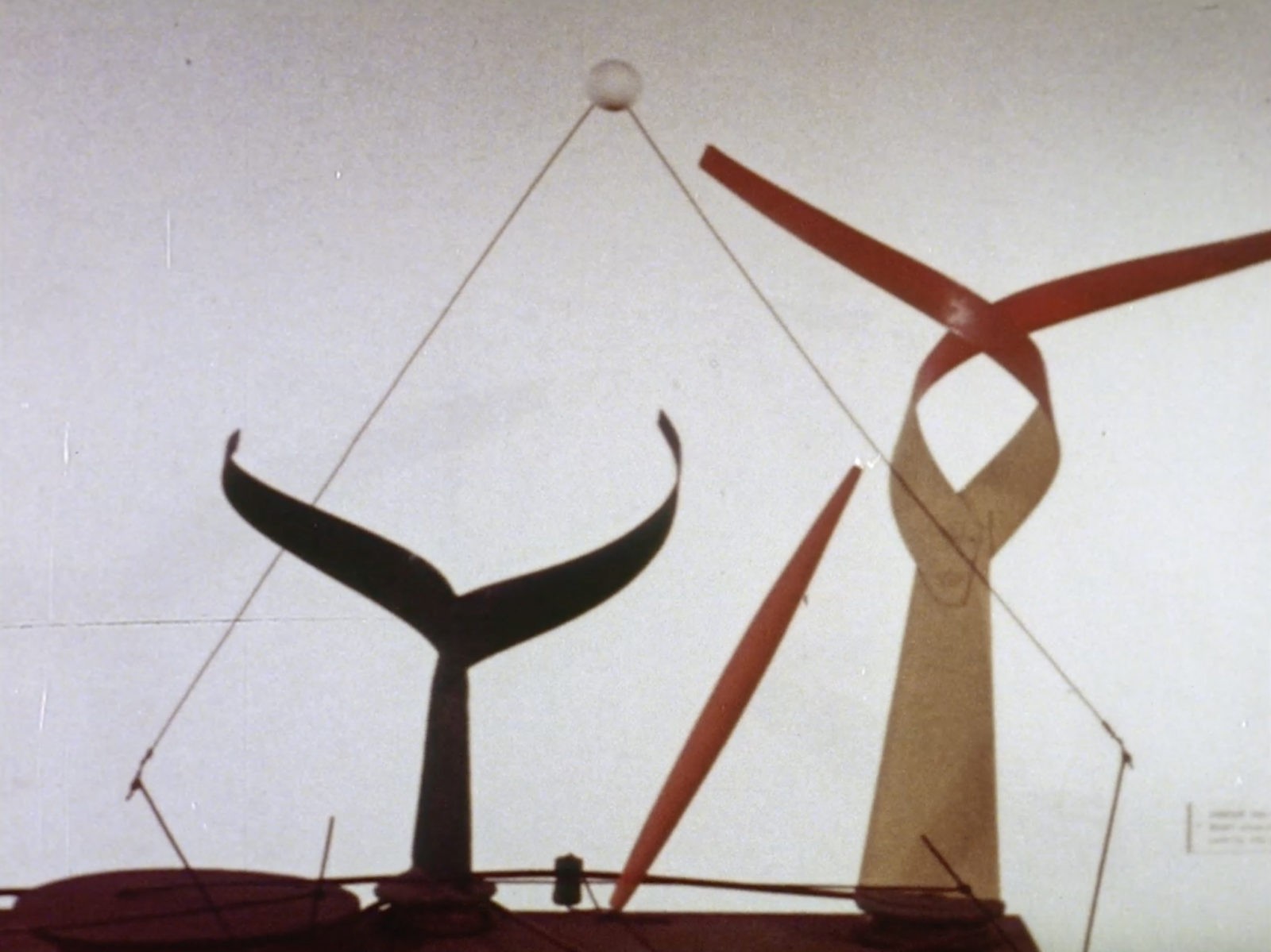

Agnes Rindge Claflin writes and narrates Alexander Calder: Sculpture and Constructions, a film based on the retrospective at the Museum of Modern Art, New York. Cinematography is by Matter.

Calder makes the acquaintance of Keith Warner, owner of a leather manufacturing company and already a patron of several artists. He also becomes a devoted supporter of Calder. Until his death in 1959, Warner commissions dozens of works by Calder, including at least ten

works of jewelry for his wife, Edna. Among these are some substantial pieces fashioned from gold.

Calder’s father, Alexander Stirling Calder, dies in Brooklyn. Calder and Louisa leave their daughters in the care of the Massons and bury Stirling in Philadelphia.

Commissioned by the Museum of Modern Art, New York, to make a work for the sculpture garden, Calder creates Man-Eater with Pennants.

Calder produces a series of small-scale works, many from scraps trimmed during the making of other objects. Let’s mail these little objects to [Louis] Carré, in Paris, and have a show, Duchamp suggests when he sees them; by taking advantage of the newly available international

airmail system, Duchamp’s action predates “mail art” by nearly two decades. Carré responds to Duchamp’s proposal. Interested show Calder miniatures would also gladly exhibit mobile sculptures available all sizes and colours.

Calder had a major show in 1946 at Galerie Louis Carré in Paris for which Jean-Paul Sartre wrote a seminal essay. He designed sets and costumes for a number of theatrical performances and designed a huge acoustic ceiling for the Aula Magna auditorium at Universidad Central de Venezuela. In 1952, Calder represented the United States at the Venice Biennale, winning the grand prize for sculpture.