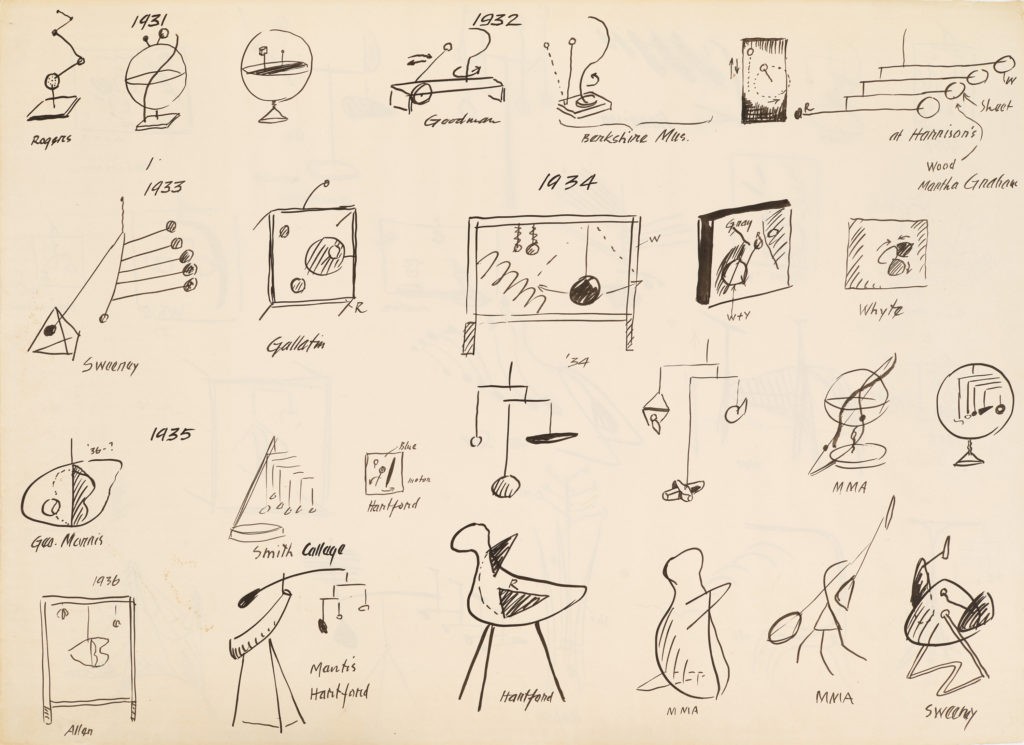

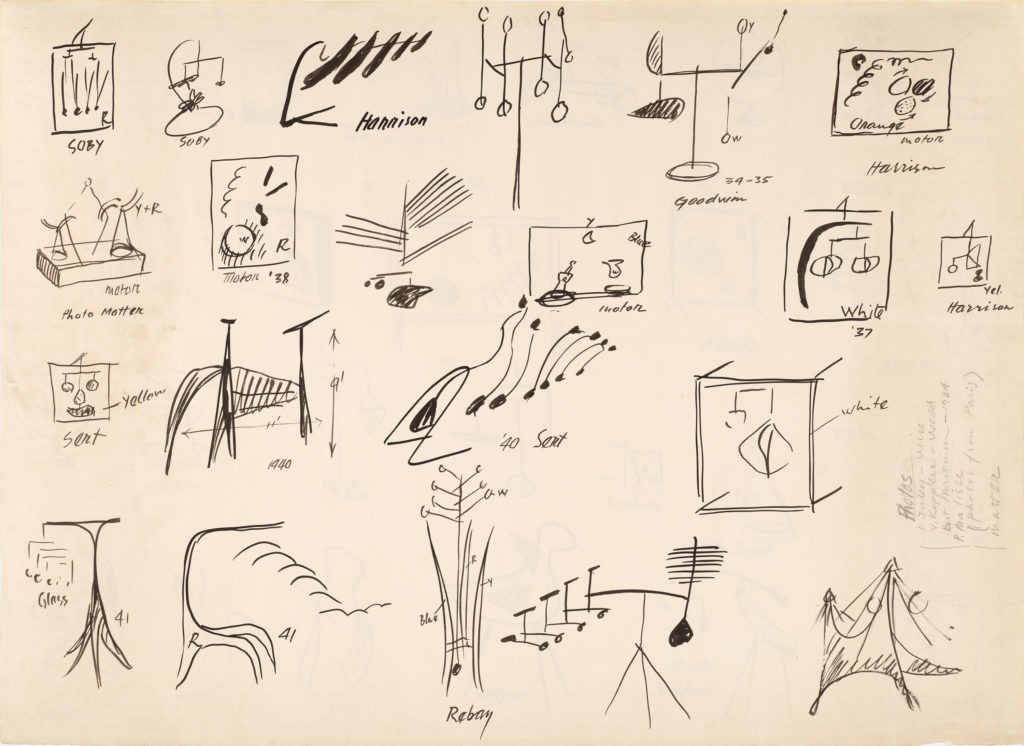

My Grandfather’s double-sided drawing from 1943 is an extraordinary document that could have been titled My Development in Abstract Sculpture. The drawing, never before published or exhibited until now, attests to Calder’s remarkably fertile relationship with The Museum of Modern Art. It was made in the lead-up to his retrospective that year at MoMA, probably after a conversation with James Johnson Sweeney, a longtime supporter and confidant as well as the exhibition’s curator. Of the forty-eight critical works defined in the drawing, thirty-two appeared in the retrospective.[1]

The illustrations are arranged in rough chronological order, beginning at the most dramatic shift in Calder’s evolution as an artist. In the late 1920s, already well known in Paris as “le roi du fil de fer” (the king of wire), he turned away from the figure and plunged into pure abstraction. “To take [this step] into the abstract field was an extremely serious departure for an artist in Calder’s position at the time,” Sweeney wrote in the MoMA catalogue. “Now those who had enjoyed what he had previously done so well were left completely at a loss.”[2] Like Picasso, Duchamp, and Picabia, Calder bewildered audiences with his lifelong dedication to self-assassinations and reinventions.

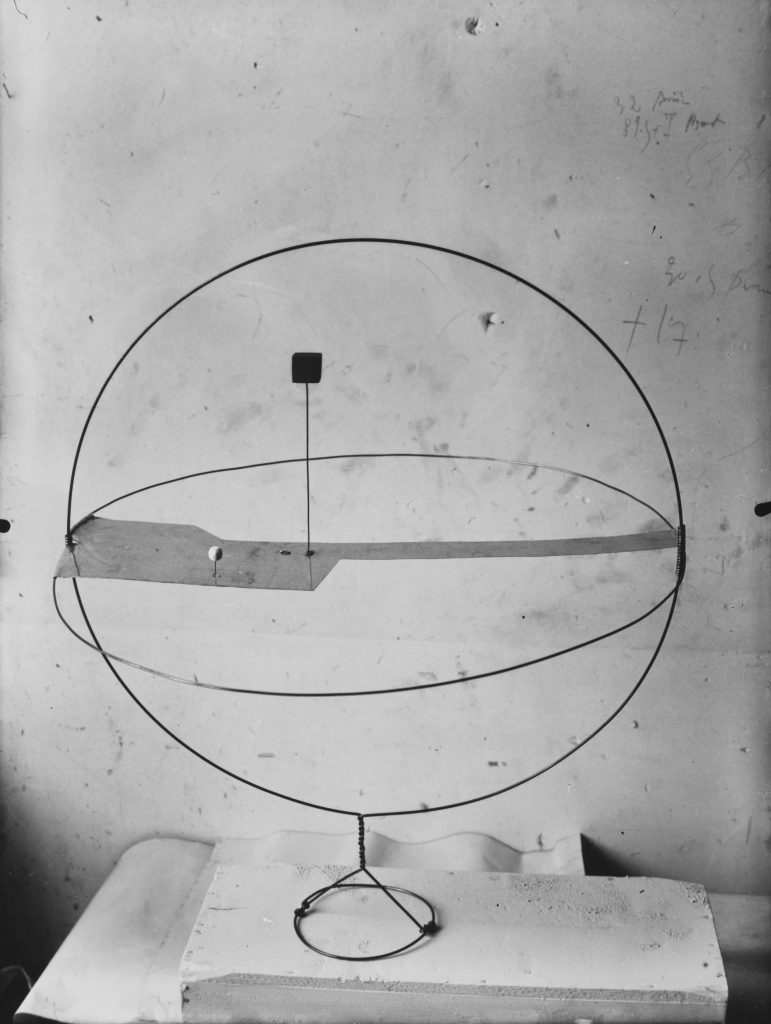

Opening the drawing’s chronology are three of the nonobjective wire objects that debuted in Calder’s 1931 show at Galerie Percier in Paris; he called those first abstractions volumes, vecteurs, densités, and sphériques.[3] The third one from the left, Musique de Varèse (1931), is a mysterious and extraordinary sphérique, with a platform of shiny, oddly shaped sheet metal cutting through the hooped void space with two objects rising out of it. Although Calder was close friends with Edgard Varèse—the vanguard composer was known to pay visits to the artist’s studios at villa Brune and rue de la Colonie—the reference to his name in the work’s title remains a mystery. Maybe it’s the way ephemeral light glances off the shiny metal that was the resonating characteristic; we will probably never know.

It is clear to me that this document was drawn in one sitting, entirely from memory. There are surprisingly few errors in the compositions of the sculptures, which span the period from 1931 to 1942 and cover a range of entirely new and radical objects, often created simultaneously: stabiles, motorized mobiles, standing mobiles, hanging mobiles, wall sculptures, large-scale outdoor works. There are no depictions of works from 1943; I assume that’s because everybody involved with the MoMA show was very familiar with Calder’s recent work. “Didn’t used to name them at all, in the beginning,” he once remarked. “When I wanted to talk about one of them, I’d have to draw it.”[4] My grandfather drew the objects with a brush, so that they were at once lucid and buoyant. His stroke easily expresses his volumetric concerns.

Although the document delineates forty-eight objects, only forty-six are drawn; the remaining two exist as annotations to specific sketches. In the first row on the front page, next to a sketch of Double Arc and Sphere (1932), is an empty space meant to represent Dancing Torpedo Shape (1932). The bracket below indicates that both works are in the collection of the “Berkshire Mus.”—a highly significant fact, as the Berkshire Museum’s purchase of these two motorized mobiles in 1933 was Calder’s first sale to a museum. “The two motor driven ‘mobiles,’” Calder wrote in the catalogue of an exhibition at that museum in 1933, “are from among the more successful of my earliest attempts at plastic objects in motion. The orbits are all circular arcs or circles. The supports have been painted to disappear against a white background to leave nothing but the moving elements, their forms and colors, and their orbits, speeds and accelerations.”[5]

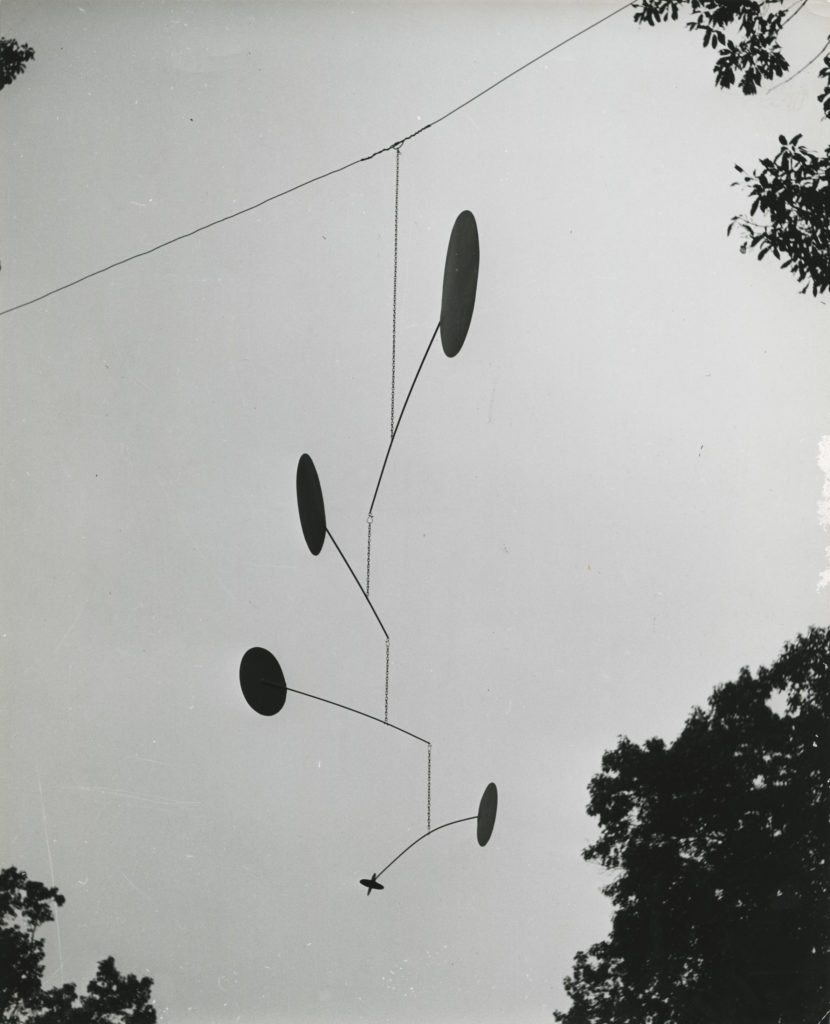

At the end of the first row is the other annotated sketch. This mobile’s first iteration was made in Paris in 1932, with large white spheres arranged over an impressive span of twelve feet. Another iteration, from 1934, was a sheet-metal mobile hung off the end of a very long diagonal rod “for the open air.” Two photographs of this version in the outdoors were published in the English avant-garde magazine Axis in 1935, with an article by Sweeney. “This and the seeming care-free spirit of his essays lift his work out of the ruck of still-born, self-conscious, contemporary experimentation,” Sweeney wrote. “Calder’s expressions seem almost spontaneous growths.”[6] On the drawing Calder identified the object as being made of sheet metal, with elements painted in white and red, and noted that it was on loan to the architect Wallace K. Harrison. Below the sketch, Calder wrote “wood / Martha Graham.” He had worked with the choreographer on two important dances, Panorama (1935) and Horizons (1936), and a version of this mobile figured into their first collaboration.[7]

There are some inaccuracies in the drawing’s timeline. It’s easy to imagine Calder getting caught up drawing an object such as Cadre rouge (1932), for example, which appears on the second row (labeled “Gallatin”), and following its lineage through other paintings-in-motion from a few years later—a lineage that functions as a dissertation on the expanded canvas. There are telling juxtapositions, such as the pairing of Cône d’ébène (1933), a lumbering hanging mobile created and exhibited in Paris, with Starfish (1934), its sister composition, made in Roxbury, Connecticut (the fourth and fifth works in the drawing’s third row). The Paris mobile is made of dense ebony; Starfish is markedly different in sensibility—made of bright mahogany and more extreme in its tension with gravity—but there are clear affinities. Steel Fish (1934) was one of Calder’s first works for the outdoors, made that summer in Roxbury; it appears to the right of Five Rods and Nine Discs (1936) in a juxtaposition that brings to mind Herbert Matter’s photograph of the works installed together on the Roxbury grounds.

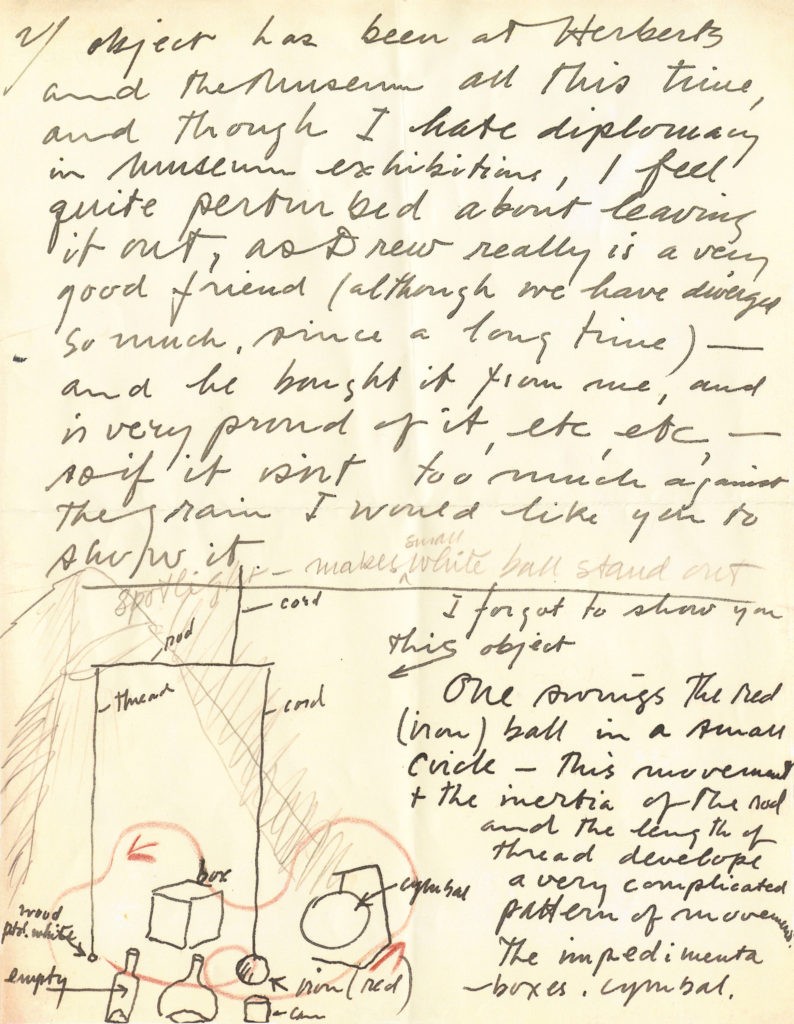

What is absent from this timeline is also revealing. In presenting it to Sweeney, Calder left out some of his most radical efforts, which might not have a place in a usual museum setting. They include the objects that remain unfinished until momentarily recomposed and completed by the viewer, such as Object with Red Ball (1931), and the highly experimental series of theatrical ballets-without-dancers, which he worked on at various times from 1934 to 1948. Of these, Objects Oscillating within a Cube (1934) is a fascinating cubic volume, with elements performing in a theatrical viewing space. This was a major effort—its model was captured in numerous photographs from the time—yet Calder left it off the list. The most significant omission from the chronology is Small Sphere and Heavy Sphere (1932/1933), a provocative interactive assemblage that included Calder’s first mobile suspended from the ceiling—a constantly unfolding composition. My grandfather later regretted the omission of this work, with its sonorous aural elements; he returned to Small Sphere and Heavy Sphere in a letter to Sweeney on August 28, 1943, finally proposing it for the show.

Although this drawing represents a procession, it also leaves us with a sensation of nonlinearity; as we look up and down and across the drawing, we can map kinships among works created at different times. It’s as though Calder was presenting the impracticalities of tracing a direct lineage. “This has no utility and no meaning,” he once said of his work. “It is simply beautiful. It has a great emotional effect if you understand it. Of course if it meant anything it would be easier to understand, but it would not be worthwhile.”[8] Even today, after decades of research, we are still only beginning to fully grasp my grandfather’s intentions and transformations. This drawing suggests the drama and exhilaration of abstraction as it reaches new heights—what Calder once described as grandeur-immense.

The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Alexander Calder: Modern from the Start. 14 March 2021–15 January 2022.

Solo ExhibitionHauser & Wirth, Somerset, England. Calder: From the Stony River to the Sky. Exhibition catalogue. 2018.

Susan Braeuer Dam, For the Open Air

Jessica Holmes, More than Beautiful: Politics and Ritual in Calder’s Domestic Items

Solo Exhibition Catalogue“Calder in France.” Cahiers d’Art, no. 1 (2015). Edited by Alexander S. C. Rower.

Susan Braeuer Dam, Calder in France

Robert Melvin Rubin, An Architecture of Making: Saché and Roxbury

Agnès Varda in conversation with Joan Simon

Magazine, MonographMuseo Jumex, Mexico City. Calder: Discipline of the Dance. Exhibition catalogue. 2015.

Alexander S. C. Rower, Calder: Discipline of the Dance

Solo Exhibition CatalogueMusée Picasso, Paris. Calder-Picasso. Exhibition catalogue. 2019.

Bernard Ruiz-Picasso and Alexander S. C. Rower, Confronting the Void

Chus Martinez, No Feeling Is Final

Group Exhibition Catalogue