This interview took place on Saturday, May 17, 2014, in Paris, before, during, and after lunch at Agnès Varda’s home and studio in the rue Daguerre, where she has lived and worked since 1951. The conversation ranges widely. It touches on her friendship with Alexander Calder, his works, the parallel subjects of fiction and documentary, ideas of light and space, the photographer’s frame, film form and content, women filmmakers in a world run by men, the restoration of early and contemporary movies, and the pleasures of eating lilacs and potatoes.

Often referred to as the grandmother of the French New Wave—having shot her first feature, La Pointe Courte, in 1954 (released in 1956), some six years prior to Jean-Luc Godard’s Breathless (1960)—Varda was also included in the Left Bank Group. That designation, as Varda notes, was invented by the critic Richard Roud to refer to Chris Marker, Alain Resnais, and Varda. (Jacques Demy was added to the group later.) Varda says that she and Roud were, in fact, friends but didn’t discuss film. Both of them held leftist political beliefs, lived on the Left Bank (of the Seine), and liked cats.[1] Varda invented the concept of cinécriture and founded a cooperative film production company called Tamaris Films in order to make her ambitious first film. The production company, now called Ciné-Tamaris, is still going strong.[2]

Agnès Varda began her career as a still photographer at the age of 19; made her most recent feature, Les Plages d’Agnès (2008), at the age of 80; and continues to work in many different media. She has created sculptural installations such as the one recently shown in her first US museum exhibition, “Agnès Varda in Californialand,” at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (2013–14). In “Triptyques Atypiques” at the Galerie Nathalie Obadia, Paris (2014), she exhibited her photo/video combines, including the wall-mounted triptychs Marie dans le vent (Marie in the Wind), 2014, and Alice et les vaches blanches (Alice and the White Cows), 2011, which feature a Varda gelatin silver print flanked by two HD videos, as well as her installation Beau comme …, 2014, a work inspired by her long-standing interest in Surrealism and, in particular, a famous quotation from Isidore Ducasse (writing as the Comte de Lautréamont) in his 1869 novel Les Chants de Maldoror: “Beautiful as … the chance meeting on a dissecting-table of a sewing machine and an umbrella.”

Varda’s work is collected in several box sets: Criteron released a set of four DVDs, 4 by Agnès Varda, in the US in 2008. Tout(e) Varda, a box set of twenty-two DVDs, was released in PAL format in 2012. Arte Editions and Ciné-Tamaris recently co-released Agnès Varda in California, a set of five films shot in California. In the US, Criterion is soon to release the same project in its Eclipse collection.

Joan Simon: The first museum shows I saw after I moved to California this past January were at LACMA [the Los Angeles County Museum of Art]—yours and Calder’s—and I wondered how you felt about those two exhibitions’ being on view at the same time.

Agnès Varda: A feeling of absolute humility, because for me Calder is a great master. He was a friend, but he was a master. He invented, instinctively, a way of re-creating the gentle movements of trees in the wind. He reinvented the beauty of nature. The architect Frank Gehry had a good idea for the installation: To avoid making the place look like a lighting store with all those mobiles hanging there, he created a little universe for each mobile; he gave each mobile its own space.

It was also important for the background of each space to be painted, so that the colors and especially the delicate lines in space of the mobiles and stabiles would stand out clearly. Also, each work had to be out of reach to avoid being damaged by visitors. That was achieved efficiently and with great subtlety.

I thought it was a magnificent idea—that’s how Calders should be seen. But you can’t do that in a gallery; it’s too expensive. Even in a museum I had never seen them displayed like that. I was absolutely delighted to see some mobiles that I had never seen before. As for the little ones, they were marvels.

I was thinking about them as I sat inside my film shack [My Shack of Cinema (1968–2013)]. I couldn’t believe my work was being shown alongside works by Calder.[3]

You are referring to the shack made out of film stock.

Yes. I was delighted and surprised to be invited to LACMA to build a film shack similar to the one I had done at the Fondation Cartier in Paris [Ma Cabane de l’Échec (My Cabin of Failure, 2006)], which I had made using strips from a burned-out 35-mm print.[4] Along with Scorsese’s Film Foundation and with help from the Annenberg Foundation, LACMA had suggested restoring the films I made in California. Then [LACMA director] Michael Govan said, “We’ll do an exhibition at the same time.” And they picked Rita Gonzalez, who I think is a very good curator. I suggested making a film shack with an old 35-mm print of LIONS LOVE (… AND LIES), one of the films I made in Los Angeles—that one was in 1968. At the beginning of November 2013, LACMA held a gala to honor David Hockney and Martin Scorsese … and, I guess, me a little bit, seeing that they had helped pay for the restoration.

Your exhibition consisted of the cinema shack, the mural with still photos and dialogues from the film, and a 1970s television set covered with an American flag and a pink boa. The entire installation My Shack of Cinema (1968–2013) is now in the LACMA collection.

I wrote out lines from the dialogue by hand on the mural because they’re worth reading in big letters. I had originally authored those lines with Carlos Clarens, a Cuban who had become an American and was intelligent, witty, and wonderful—actually, he was writing a book about Richard Brooks at the same time. He helped me write the dialogue. He had an ear for the hip style of talking in those years at the end of the 1960s. We realized that there were things we could say, we could call a spade a spade. So I listened to him; he assisted me. Gerome Ragni and Jim Rado, the writers of Hair, who were both acting in it, helped me too. Sometimes they came up with phrases like, “I hate all kinds of entertainment, including living”—you see what I mean, phrases like that, and I love them. And Viva, too. She was full of life and very inventive: “All the dead actors have turned into cockroaches. That’s why there are so many of them in the hotels here.” I would say “Three is a perfect number” because that was obviously what the film was about. At the end of the 1960s there were buttons everywhere, those funny little badges with messages on them. I loved those buttons, so we enlarged them and put them on the mural.

There were buttons with slogans like “Poetry Not Poverty” on the mural, along with stills from LIONS LOVE and lines of dialogue.

There was one button, I remember, that read, “Sterilize Johnson, we don’t want any more ugly children”—funny things like that, which were aggressive at the same time. I think people have calmed down now, apart from a few punks and singers. But it was fun, because that period set something free in me, too. There is a bit of punk in all of us and a bit of the hippie.

Jacques [Demy] and I arrived from France, with our French culture—interesting, organized, and logical. For me it was a marvelous moment of liberation to show up in Los Angeles in 1967, with the flower children, the hippies, Marshall McLuhan (“the medium is the message”), the Vietnam War, pop music, and, of course, the Black Panthers, whom I filmed.

Let’s take a break. I’ll put some water on to boil potatoes. They are a very special kind, from the island of Noirmoutier; they’re called Bonnottes. They grow in sandy soil and they’re fertilized with seaweed. At Christmas, you spread seaweed over the ground; you wait until the seaweed goes soggy, then you dig it into the soil and plant your potatoes. When you pick them and eat them, they’re like little cakes. I’ll cook you some so you can taste them.

Thank you.

Just simple boiled potatoes—you’ll see how good they are.

You’ve done quite a few films with potatoes, and a big installation.

Great big potatoes shaped like hearts, filmed as if they were breathing.

And there was your potato costume at the Venice Biennale—what was that about?

Oh, that was just for fun. I did that for a laugh … and out of shyness. It was the first time I had been invited to a Biennale.

After you had worn it, you said you left it as part of your installation at the Biennale.

No, no, not at all … Patatutopia [2003] happened by chance, because in the movie Les Glaneurs [The Gleaners and I, 2000], I followed trucks that were dumping the potatoes that were too small or too big for the standard size sold in the supermarkets. Of course the potatoes go green in three days. But people come and pick them up. So, in Les Glaneurs, I filmed a guy who’d gone along straightaway to the places where the trucks had dumped them, and picked them up—gleaned them, in fact. He put them into sacks to sell them …

He said, “There are big ones, small ones, ones that look like monsters; there are even some heart-shaped ones.” And I said, “Oh, I want the heart-shaped ones, I want the heart!” So I brought all these heart-shaped potatoes home with me here and I started to film them. Then I put some on glass, in the light; I put some in the cellar, in the dark; and I put some in a cardboard box. And they grew like that. In other words, I started aging potatoes and filming them. I was happily occupied filming my potatoes when [Hans Ulrich] Obrist invited me to the Venice Biennale. He had interviewed me in a book called Interviews.[5] He had already noticed my films.

Anyway, Obrist invited me to be in a section called “Utopia Station.” One of the utopias involved bringing people into the big, official house of the arts who weren’t yet part of it, including me.

I was overjoyed because what I wanted to do was to present three big screens. I already had nearly all the material.

On the central screen you could see those heart-shaped potatoes breathing. And on the two sides you could see all the shoots that had grown and the new thin roots. Those wrinkled old potatoes that just kept growing and germinating—I thought it was quite beautiful. I was already seventy-six years old. It’s kind of silly to say so, but it was very invigorating for me. I was old and I was still creating life, germinating.

When I was watching your film L’Opéra-Mouffe [1958; released in English as Diary of a Pregnant Woman] I was struck by the balance between the joy and beauty of the young couple and that of the older people.

The film was mostly inspired and motivated by my pregnancy. As I said in the DVD extra of Varda Tous Courts, I was very happy to be pregnant.

What I was hoping for included the hope of happiness—happiness, whatever that might be—for the child. And I was watching people in the rue Mouffetard, old people, drunks, cripples, lonely people, and all those bums. My feeling was that I was looking at these poor people as they were, but they were all babies once. And when they were babies someone planted kisses on their little tummies and powdered their bottoms. They all started out as babies. And there was love for even the unexpected and the unlovely children when they first arrived.

The film is so tender—the shots of the couple in bed, just their eyes, their faces next to each other, one of them holding a foot, and when they are on the street kissing and the older people are looking at them with pleasure.

Pleasure or envy. All those people are so abandoned, so lonely—poverty and solitude in old age is a terrible thing, in the cafés … I thought those people … Oh, I was so grateful that they let me film them.

There was something that surprised me at the end of the film: the shot where she eats the flowers.

Those tiny lilac flowers are very good to eat—they’re very sweet.

There is a chapter heading that says “Les Envies,” which means “longings,” just before she eats the lilacs.

The short song at the beginning of the chapter talks about desires and longings. People always say that pregnant women have longings.

There is something else, too. There’s a certain confusion between the fat belly you get when you are expecting a baby and the fat belly from eating too much. At that time, there were people selling incredible meat products. It doesn’t happen any more. Those parts of animals that they call lights—the lungs and the spleen, those rather disgusting parts—are no longer sold. And the song you’re talking about goes, “Entre le dégoût et l’envie / Entre la pourriture et la vie” [Between disgust and desire / Between decay and life]. They were little haikus that Georges Delerue set to music, very beautiful music.[6]

What really surprised me when I watched and listened to your film was that it reminded me of an Alice Guy film called Madame a des envies [Madame Has Cravings]. It’s about a pregnant woman who …

Ah, I don’t know that film, but I know that you’re an Alice Guy-Blaché specialist.

It’s very funny. It’s a chase—she’s dragging a baby carriage behind her and an unfortunate husband, and she keeps stealing very phallic food from passersby. She steals a banana from a tramp, some absinthe from someone else, then she steals a lollipop, and there’s a close-up of her sucking on the lollipop.

I didn’t know she had such a sense of humor.

Oh, it’s really funny.

It’s sexy.

But when I saw the way you approached the subject …

It was very different.

Totally different, but …

My approach to those people was one of tenderness, as if I could pass on to those desolate people some of the tenderness that I felt for the baby I was expecting, and I really piled love onto them. I prepared for the film on my own by taking photographs. I’ve got some really good photos of the rue Mouffetard. I didn’t have any equipment for the shoot. Somebody had lent me a 16-mm camera. Then I would fetch a garden chair and take it into the street, I would stand on the chair, fix my tripod, and start filming. In the time between the preparations for the film and the actual filming, some of those tramps—I was already very affected by homeless people—some of them had died of cold. I mean, at the time, I was already disturbed by the idea of people dying of cold. You find this in Sans toit ni loi [1985, released in English as Vagabond]. Do know that film? At the end, she freezes to death.

I edited L’Opéra-Mouffe in my bedroom—I had very little money then, but I managed to finish the editing and put in Delerue’s music with the money I had earned as a photographer. There was an international fair in Brussels in 1958 and the director of the Cinémathèque Royale de Belgique, a wonderful man named Jacques Ledoux, set up an experimental film festival. He invited the obvious people: [Paul] Sharits, [Ed] Emshwiller, [Jonas] Mekas, [Michael] Snow, [Stan] Brakhage, and others—all the American experimentalists from the ’50s. And he invited me, too. I said to him, “I don’t know if my film L’Opéra-Mouffe is experimental.” He said, “But was it an experiment for you?” And I said, “Yes.”

The black and white in that film is so beautiful, the light—

It’s winter light, it’s beautiful. I was already a photographer, so I knew how to frame a shot.

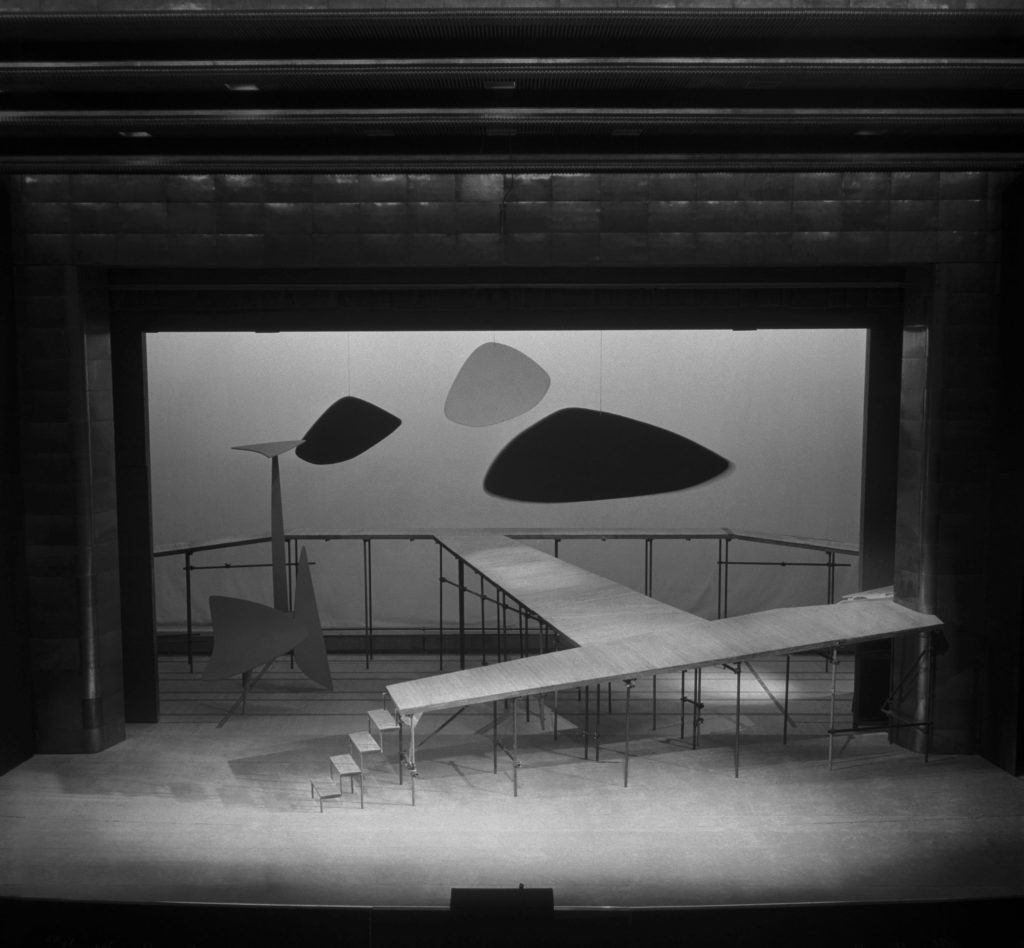

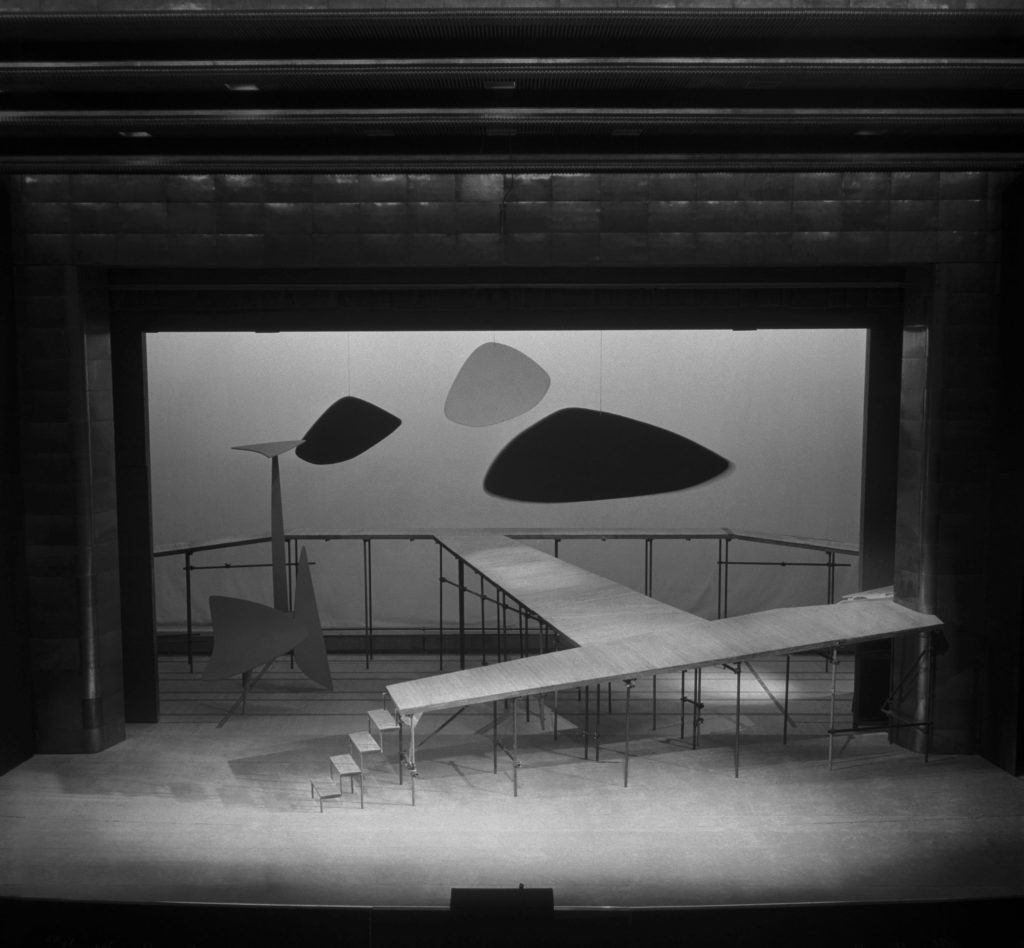

Did you first meet Calder in your role as a photographer at Jean Vilar’s Théatre National Populaire, when he was designing the sets and costumes for Nucléa in 1952?

Maybe before. When Calder came to Sète, which is Jean Vilar’s hometown, I saw them. I took pictures of them on the beach.

According to the Calder Foundation archives, Calder performed his Cirque Calder in 1953 at Galerie Maeght.[7] What was it like to see him perform?

Oh, you can imagine how it was: this man, slightly plump, sitting on the floor and manipulating tiny, tiny little things that he had made himself. He would hang the trapeze artist on the trapeze and he would make the whole thing move. He was very ingenious. It was all done with strings and wire. It was funny and it was marvelous to see him laughing as well—especially when he was sweeping up the lion shit …

Have you seen the little film about the circus?

There are two films: one by Jean Painlevé and another by Carlos Vilardebó. Jean Painlevé’s film is very well done. Painlevé observes Calder the same way he looks at sea creatures in his underwater films: The camera stays still, facing straight ahead. Calder wears a dark blue shirt, not his usual red one, so he sort of fades into the background, like a Japanese puppeteer. Vilardebó’s film is a little more …

Carlos’s is more complicated.

Yes, the point of view moves around.

Carlos was my assistant and my savior on my first film, La Pointe Courte. He had made short films, but he hadn’t done the Calder yet. He helped me in 1954.

How?

He persuaded me to make the film! Because I’d written my screenplay, like a poem that you put in a drawer forever. I had never been taught, I had never been to film school, I knew nothing about films. I’d only seen half a dozen or a dozen films. And we met and he read the script and said it would be a nice film and I said, “So what do we do?” And he said, “Let’s get it organized.”

He got the crew together, a tiny crew: He was the assistant and also was the grip. His wife was the script supervisor. We found a cameraman—an old man … he was thirty-two! We rented a house and we all stayed in it. No hotels, no restaurants. Somebody came and did home cooking for us.

I asked all the actors to come and work without pay—we didn’t have any money at all. The money was for the film stock, for renting the camera and the house, and for buying food. The actors were fabulous. It was Philippe Noiret’s first film … Silvia Monfort had already acted in a Cocteau film. They were very generous. My first film was made as a result of everyone’s generosity. Alain Resnais, who was an editor, had already made a short, and he agreed to edit my film for no pay. It’s a miracle that it exists.

Nobody directed a film at twenty-six years old, because you had to be an assistant first. You had to wait. Third AD, second AD, and so on. Even Antonioni came to France to be [Jean] Renoir’s assistant.

From the very beginning of your filmmaking, with La Pointe Courte, there has always been a mix of documentary and fiction. Why is that?

It’s obviously impossible to enter into somebody’s private life and their social life at the same time. I definitely feel that, in life, we want to know about the difficulties other people experience, about politics, society, the trade unions. And at the same time we also want to be alone, to be in good health, and, if possible, in love and to snuggle down under the blankets. You can’t mix these things together in films; all you can do is juxtapose scenes—show parallel worlds. That’s what I felt. For the construction of the film, I took my inspiration from the structure of [William] Faulkner’s Wild Palms.

Could you please talk about how you told the parallel stories of the couple and the fishermen in La Pointe Courte?

It was very straightforward. Ten minutes of the fishermen and their family life, then ten minutes of the couple walking and talking, then ten minutes of the fishermen, and so on.

Even though it was filmed in the same place, there was no real connection beside the place and maybe a phenomenon of osmosis.

What you say about La Pointe Courte reminds me that that mix of fiction and reality is also an important part of the Cirque Calder. Not long ago, when I was doing research with a team trying to work out how to conserve Calder’s circus, we discovered that, although we thought that Calder had stopped doing documentary sketches when he stopped doing illustrations for the National Police Gazette in the mid-1920s, in fact he hadn’t.[8]

He stopped doing what?

In the mid-1920s, Calder was doing drawings for a publication called the National Police Gazette, about goings-on in New York. One of these drawings was Seeing the Circus with “Sandy” Calder [1925]; another was “Sandy” Calder Goes a-Sketching at Coney Island [1925]; and there was a third one called “Sandy” Calder Sees “The Goldrush,” Charlie Chaplin’s New Film [1925]—things like that. The question we were addressing when we were researching Calder’s circus was, how do you conserve a performance, not just the objects?

You have to film it, that’s how!

The films of Calder performing his circus were made decades after he began to create it and perform it in the late ’20s and early ’30s. When you look at the later films of Calder’s circus, you see one thing, and when you look at the objects themselves, you’re seeing something else that has survived. We know that when he was working for the National Police Gazette in the mid-1920s, Calder drew the Ringling Bros. and Barnum & Bailey circus in New York. In order to research circuses of the period and how they might relate to the creation and performance of Calder’s circus, and because I was also researching into early cinema and the connection with Alice Guy-Blaché’s films, I took another look at the early films of Ringling Bros. and Barnum & Bailey in the 1920s, and also films of the Fratellinis in France.

But did anyone film Calder’s circus in the ’20s?

No. Not as far as we know. There are a lot of photographs of him with his circus at that time, including photos by Brassaï and Kertész. When we watched the 1920s films of Barnum & Bailey, in spite of the fact that we thought that Calder’s circus was pure invention on his part, we found that it was actually a mixture of fiction and documentation—looking at each act, you can see which ones he invented and which ones he based on actual circus acts. One example is the scene with the equestrienne, wearing her signature big, pink bow in her hair and performing a distinctive jump-rope act. Standing on her horse as it circles the ring, she jumps a rope as it lands below her feet yet above the horse’s back. (The end of the rope is held by the tiny lady trainer at the edge of the ring, the other end is held in one of Calder’s large hands). Calder’s is actually a miniature and abstracted version of a real act from Ringling Bros. and Barnum & Bailey. May Wirth was the equestrienne.

Those acts are classics anyway, they’re standards. When you see Sandy sweeping up the lion’s droppings, that’s something you always see at the circus. I think he loved the circus, like I used to love the circus. I didn’t go to the movies between the ages of twenty and twenty-five, but I went to the circus every month, every two weeks. There were two big circuses in Paris—the Cirque d’Hiver and the Médrano.

What was wonderful in Calder’s little circus was the proportions—of things he had made with his own hands.

He didn’t use his hands just to operate the acts in his circus; he also sewed all the costumes and things by hand.

Watching him handling the little felt animals and seeing his great big shoes wiggling about was really funny. It was like watching a big child having fun. And he would laugh. Calder’s laugh was extraordinary. It was the laugh of a young person with the mind and the imagination of an adult artist. Did you see the photo of Sandy in my courtyard? He was playing with the children and balancing on a little scooter. It was a joy to see him.

Calder’s allegory of the “clothespin ladies” act is based on the Ringling Bros. tableaux vivants with women as living statues. Even his little clown, you know, the one that smokes a cigarette and blows up a balloon—the one with the very hairy legs. I saw the same hairy legs in one of the Fratellini clown costumes in a 1920s film of them, and also in a drawing by the Vesque sisters, who documented French circuses of the period. In the film, you see him pulling up the leg of his pants to show off those great long rubber-tubing “hairs.”

I saw this type of clown act. Calder invented a very original way of representing them. Another circus standard is the ping-pong banter between the clown and the ringmaster. You don’t get that with Calder.

There is a ringmaster in Cirque Calder. It’s Calder’s voice. In French circuses there’s a lot of dialogue, but there isn’t very much in the American circus. In Barnum & Bailey and the other American circuses, the ringmaster just announces the acts.

In Les Plages d’Agnès you have a scene on the beach with trapeze artists.

Yes, of course. You see, because I was so extremely fond of the circus, and because I thought that that film might be my last one with a crew and everything, I felt I should indulge one of my daydreams, which was to have a circus on the beach, where you see the acrobats and the trapeze artists as if they were flying fish. We had to build a tower so as to be in the right position to film them flying and jumping, with the sea in the background.

It was a fantasy. I’m so glad we got to do it.

Why were you so very fond of the circus?

Oh, I don’t know. Some people love music, some people love films. I loved the circus when I was young: Really, it was my favorite kind of entertainment. There was nothing more beautiful than the circus. I even learned to play guitar with a clown. He was called Frédo. You know, clowns are musicians. They can play three or four instruments.

How was it that you took photographs of Calder’s Cirque while he was setting it up for a performance at Maeght?

He phoned to invite me. Actually, I should have said, “Let me come half an hour before, so I can do some close-ups.” I was stupid not to. So I took the photos during the show, and they’re all taken from the same viewpoint.

I think what’s so important about the Cirque Calder is that it was performed as an ordinary event. I mean that it was a part of his life, and the components of his circus weren’t created as precious objects. Calder used them and played around with them. It’s only when you see them in a showcase in a museum that they look like sculptures.

Did you ever visit Calder in Saché?

Yes, I went to see him there, with his family. I didn’t take any pictures, though. They lived in a water mill. They had put in a window in the main room, a low window with a fireplace above it, so you had the fire and the window just below it, and you could see the river flowing under. It was really beautiful!

He lived there with Louisa and the two daughters. I’m still in touch with [Calder’s daughter] Sandra Davidson and I see her from time to time. She loves patchouli. She doesn’t seem to be very involved with the Calder Foundation; Sandy Rower is the one who looks after that. I knew him when he was a baby. His mother was Mary, the second daughter, who died.

Yes, Sandy heads the Calder Foundation. Had you seen Calder exhibitions when you were a student in Paris, before you met Calder?

I guess I didn’t miss them. His art was new and intriguing.

In 1951, you became the photographer at the Théâtre National Populaire?

Because I knew Jean Vilar. His wife was my neighbor in Sète. And I always spent the holidays with them on the beach. When Vilar started his Avignon festival, in 1947, I wasn’t there. But the second year, in 1948, he said, “You have to help.” It’s always the same money problem. “If you help, we’ll get you a hotel room, if you take a few pictures.” But the first year I took the photos, they were all out of focus, I couldn’t do anything about it, I didn’t have fast film, I didn’t realize. So I think that in 1948–49, I hardly did anything. The next year I started to take better pictures.

And when Gérard Philipe came to the festival in 1951, there was a rush of press requests because he was a movie star. I took some very good pictures then. They’re very well known, as theater photos.

And that’s how the newspapers noticed my work and asked me to do assignments. And I also started to do photo compositions for myself. I never sold any pictures back then, and I never had a show. I don’t know why. I’ve never made a book of my old photos, either. Anyway, at Paris Photo in the middle of November, in Galerie Nathalie Obadia’s stand, I will show, for the first time, the eighteen “vintage” photographs that I displayed in my courtyard in June 1954.

At the Théâtre National Populaire, Jean Vilar directed a production of Nucléa, written by Henri Pichette, and you took photos of the play. Jeanne Moreau was in it … and Calder designed the sets.

Yes, he designed footbridges placed on metal tubes, a very vertical red stabile, and four mobiles hanging above the stage. It was beautiful.

And there were two necklaces.

Which he made himself for Jeanne Moreau.

And I believe he also designed a bracelet for Nucléa.

Yes. I’ll tell you something. Once Vilar, Calder, and I were driving to the Abbey of Fontfroide in the South of France. We stopped to look at the scenery, and we opened the trunk to get a bottle of water, which was next to Calder’s toolbox. And he said, “Would you like me to make you a necklace?” I said yes, and he took a piece of flat metal and cut it into a pattern of curves, and then he gave it to me, just like that, in the middle of the road, and we closed the trunk. That’s the one he gave me.

There’s a letter in the Calder Foundation archive from him to you, dated May 12, 1955, that says: “I asked Foinet to give you a mobile— your choice—among many, of a medium size that I left at the studio. I hope that you want it—but I know that that could take up a lot of space, if it’s too big—if nothing suits you, I’ll make you a custom size one on the next visit.”[9]

And you did choose a mobile.

It was wonderful of Calder to offer to make me a “custom” mobile!

Alexis Marotta, director of archives at the Calder Foundation, told me you wrote a beautiful thank-you letter and sent four photographs. On the card you wrote, “Vive Calder.”

Perhaps. But it was only natural, wasn’t it, to send a nice thank-you letter? The letter he wrote to me had a very beautiful envelope—he had made it himself. I guess I must have sent him a funny envelope too, I don’t remember. He used to come here, to the courtyard, and we would make paella. He enjoyed the best things in life. It wasn’t so much about eating, as I said before, it was about being together, playing with the kids. Just nattering, for the sheer pleasure of it. He made me realize what a privilege it is not to be ill or stupid.

One other question for you before we go look at your photos of Calder. Did you ever dance with him?

Yes. Like all sprightly, fat people, he was very light on his feet. We went to a dance in a neighborhood in Sète, le Quartier haut. I have some pictures but they’re a bit out of focus. It was a local dance. He danced. He was very natural with everybody there—utterly attentive to whomever he was with.

It was nice to see the whole family. There’s a famous photo of the four of them—Sandy; his wife, Louisa; and his daughters— sitting on a bench on the boulevard Saint-Germain. They had the same body type, all four of them, and were so beautiful and so peaceful together, I was really struck by it.

And there’s one more question I forgot to ask about Nucléa. On the opening night, there was a protest at the theater by the Lettristes.

Oh, that was because they were furious with Pichette, because his theater wasn’t a Lettriste theater. It was [Jacques] Copeau and [André] Antoine, in the ’30s, who invented Le Théâtre National Populaire [the TNP], and the concept was brilliant compared with the bourgeois theater. The TNP was revived by Vilar [in 1951–63]. His theater was wonderful—it wasn’t expensive, you didn’t have to pay tips to anyone, and the cloakroom was free. The full text of the play was in the program, which cost next to nothing. The TNP was unbelievably good. Vilar’s repertoire covered classical as well as radical new plays by writers from Molière to [Armand] Gatti and Pichette.

I remember, from reading interviews with you … being very touched by the way you talk about being a feminist but keeping a certain independence in your life and the way you work. In other words, you can be a feminist but it doesn’t necessarily have to be the subject of all your films; it can be touched on indirectly.

It’s a way of saying, I can be a feminist and an active one, and it shows in my films, but I don’t want to become the spokeswoman of the feminist cause in film. In the movie business, it’s important to fight for innovative films, for what I call cinécriture: a real cinematic language, which tries to use images and sounds differently, rather than just adapt books or plays. I like it when a film comes from nowhere, grows out of a subject, from the urge to make a film and you find a way of structuring it.

Could you talk about your structuring of Sans toit ni loi?

A woman walks around and meets people, who talk about her. It’s an impossible portrait to get right. We know virtually nothing about her, but I constructed the narrative of her comings and goings and how she survives, until she eventually dies. You have to find your own personal cinécriture. Take Robert Bresson: He had a way of filming that was utterly unique to him, and secret.

And your film Les Plages d’Agnès?

Before I did Les Plages d’Agnès, I reread the preface to Montaigne’s Essays and, like him, I wanted to show my grandchildren and my friends and a few other people some aspects of my life and how I had started out: the people I had met and who were important to me—like Calder; the people I had loved and who loved me—Jacques, my children. And my work, my films.

In Les Plages, you show yourself walking backward—

But I’m turning toward you all the time. I’ve had a full life, but not a life full of incredible or extravagant things. I’ve never escaped from prison; I’ve never been raped or had to put up a brave fight against cancer. It has been a life full of little events and discoveries, and work. And beauty and love and pain, like everybody else. The trick in that film was to find a form, a narrative, a rhythm and a certain fluidity in order to generate energy and to filter into it a hidden melancholy that would reach people.

Hauser & Wirth, Somerset, England. Calder: From the Stony River to the Sky. Exhibition catalogue. 2018.

Susan Braeuer Dam, For the Open Air

Jessica Holmes, More than Beautiful: Politics and Ritual in Calder’s Domestic Items

Solo Exhibition Catalogue“Calder in France.” Cahiers d’Art, no. 1 (2015). Edited by Alexander S. C. Rower.

Susan Braeuer Dam, Calder in France

Robert Melvin Rubin, An Architecture of Making: Saché and Roxbury

Agnès Varda in conversation with Joan Simon

Magazine, MonographMuseo Jumex, Mexico City. Calder: Discipline of the Dance. Exhibition catalogue. 2015.

Alexander S. C. Rower, Calder: Discipline of the Dance

Solo Exhibition CatalogueMusée Picasso, Paris. Calder-Picasso. Exhibition catalogue. 2019.

Bernard Ruiz-Picasso and Alexander S. C. Rower, Confronting the Void

Chus Martinez, No Feeling Is Final

Group Exhibition Catalogue