In her article “Arts Parallel,” Nancy Cunard wrote the words “inter-bound and interinspiring” about the “un-academic, the experimental, the iconoclastic, pre-eminently creative” ways that the arts of “today” were “belonging to each other.”[1] Writing as she did in 1947 from the pages of Jazz Forum magazine, her emphasis was on the ways in which artists crossed over, inspired each other, and moved between different forms of artistic expression. It also sounded the resurgence of the arts in post-World War II Paris, a time and a place that was marking a slow comeback following the devastation of the Nazi occupation.

Cunard experienced first-hand the threat of fascism during the 1930s and early 1940s. Throughout the Spanish Civil War, she worked to raise funds in support of Republican Spain by editing together and publishing the work of poets who were sympathetic to the cause. She reported from the Civil War’s front lines, traveling between Madrid and Barcelona, and at the war’s end she covered the horrific conditions of Spanish exiles in French concentration camps. While in England during World War II, she published poems and edited literary projects in support of the French resistance.[2] Thus, when she returned to Paris in 1945, Cunard was sharply aware of the intersection of art, poetry, and war, a sensitivity that emerges in her observations about the synergy of artistic forms. As she observes, artists, their works, and the worlds in which they live “belong to each other.” However, it isn’t a passive or generic kind of relation that Cunard describes. Rather, it is the propulsive kind of inter-boundedness that fuels collaboration and creativity.

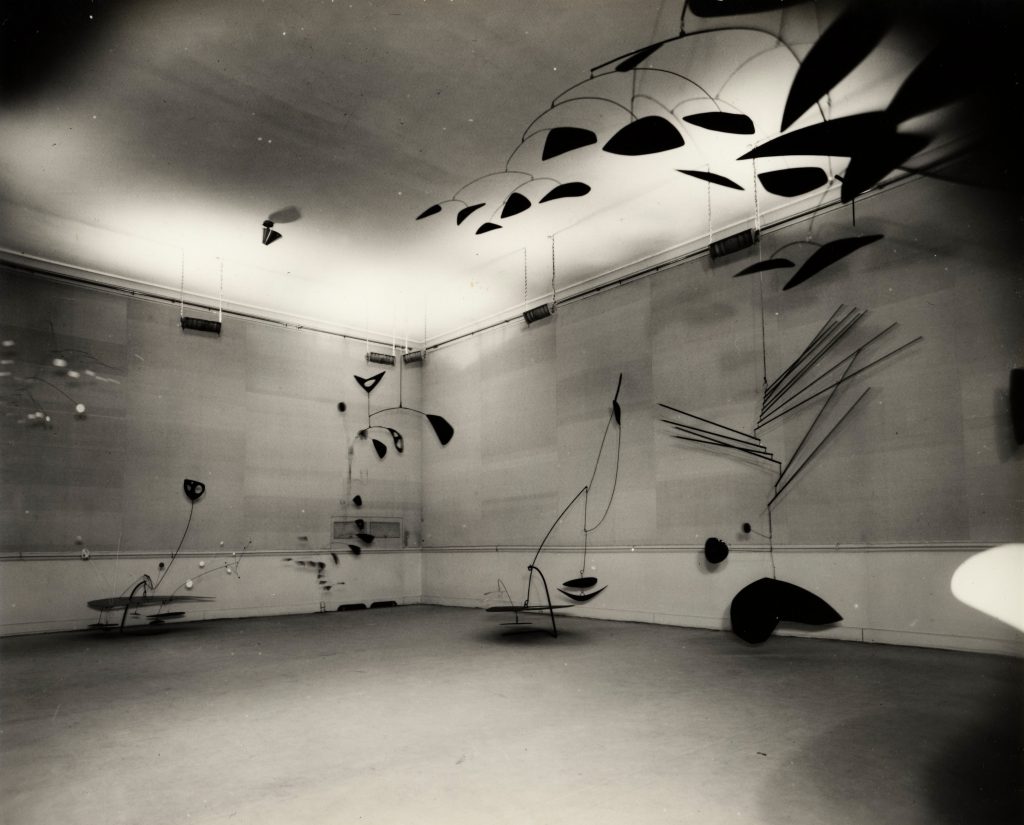

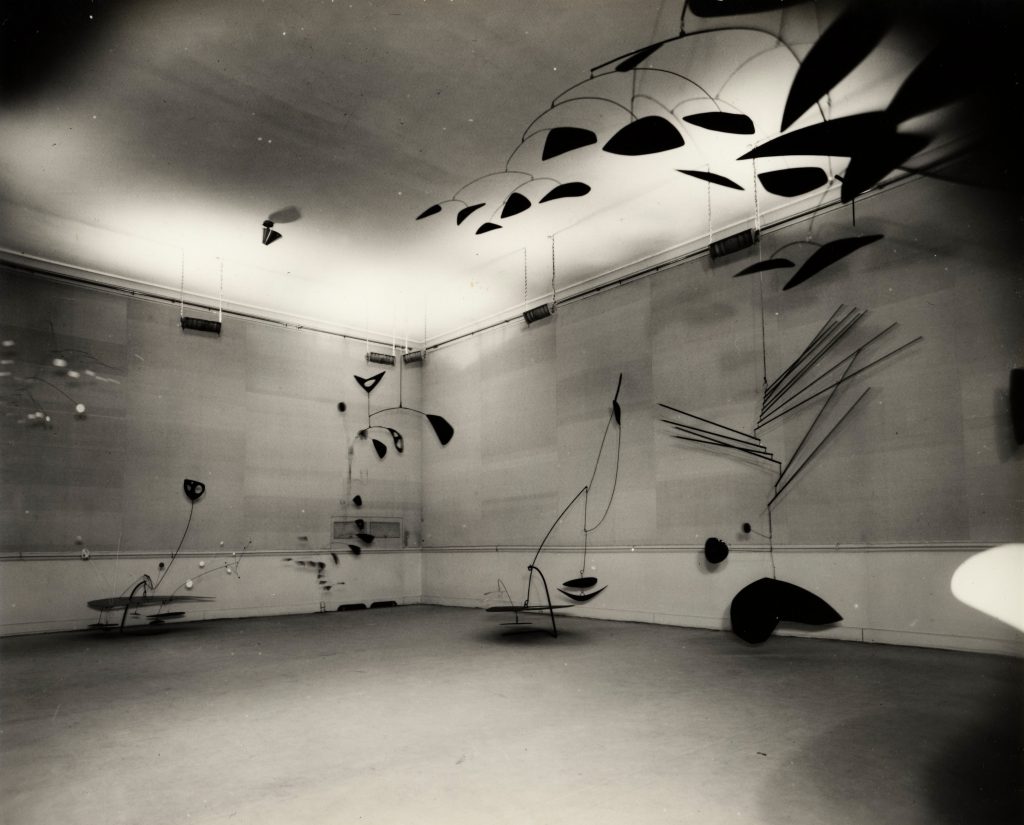

In Cunard’s review, she highlights Alexander Calder’s work as exemplary among contemporary artists and reminds her readers of his remarkable Mercury Fountain (1937), installed in the Spanish Republican Pavilion at the Paris Exposition Internationale ten years earlier. Her reflections were written in part in response to Calder’s 1946 exhibition at the Galerie Louis Carré, and she cites at length Jean-Paul Sartre’s preface to the exhibition’s booklet-catalogue. Sartre’s description of Calder’s mobiles captures the fascination that they held for many artists, writers, and musicians of the period. “They are resonators, traps,” wrote Sartre, putting into words the complexity of Calder’s pieces: they amplify and capture, expand and retain, bring our gaze in and push our senses out.[3] It is no wonder then that Cunard should reproduce Sartre’s prose, as she herself was sensitive to both the poetic and political dynamic that modern art could hold. Toward the end of his preface, Sartre added this about the experience of visiting Calder’s studio and the unpredictability of his mobiles, moved by the slightest breeze: “These hesitations and resumptions, gropings and fumblings, sudden decisions and, most especially, marvelous swan-like nobility make Calder’s mobiles strange creatures, mid-way between matter and life.”[4] Sartre’s observations here are especially keen given that, with telegraphic precision, he homes in on a deep complexity in the work of Calder, and that of many of Calder’s artist-friends: the simultaneous draw of matter and life, the materials of art and the moral commitments of the artist’s mind, whether they be aesthetic or political.

Ten years after the artist’s contribution to the Spanish Pavilion, Cunard emphasizes for her readers, through both her own writing and her references to Sartre, that Calder’s work is timely and relevant because it holds the possibility of joining contextual meaning with experimentation in form. It is about the individual viewer’s experience, as well as how the artist’s work extends from the individual to bigger ideas about movement, and the way forms and their creators are connected through the experiences and perception of the viewer. Calder’s mobile activates that relationship and keeps it alive through repeated experiences with the work over time. Calder, like Cunard, supported the Republican cause during the Spanish Civil War; they, along with many of Spain’s own artists, worked to find a bridge between modern artistic idioms and deeply personal commitments to the political and personal stakes of war.

It is thus no slight detail that in her review Cunard brings her readers back to 1937 and to the Spanish Republican Pavilion. It was in the Pavilion that synergy between the arts (architecture, painting, and sculpture) was scripted through the selection and placement of work to support the political cause of the Republic; the success of the Pavilion depended upon the artists’ ability to activate viewers’ response to the work, and to transform that response into moral, or at least political and economic, action. As the works commissioned for the Pavilion evolved, and as artwork and objects arrived in Paris from Spain for exhibition within the Pavilion, it became clear that Calder’s contribution, added to the already planned mural paintings of Miró and Picasso, activated and triangulated the crucial role of modern art in raising the Pavilion’s profile for its international audience. As well, it consolidated the position of these artists as staunch defenders of the government’s fight against the military coup that had instigated the civil war the year before.

The occasion of the Spanish Republican Pavilion was a pivotal moment in the careers of all three artists, as well as a landmark occasion for their work to be exhibited together. In the case of all three artists, their work for the Pavilion was created in response to their outrage over the Spanish Civil War; their commissioned pieces for the Pavilion were placed within an architectural setting, designed by Josep Lluís Sert and Luis Lacasa, that positioned painting and sculpture, fixity and flow, in dialogue. The plan for the Pavilion combined standardized industrial materials with a study of visitors’ movement through the space, such that visitors had to first cross the ground-floor patio that housed Picasso’s Guernica and Calder’s Mercury Fountain before approaching the stairwell that brought them face-to-face with Miró’s mural The Reaper (immovable and painted directly onto Celotex tiles). Throughout the Pavilion hung work from Spain’s leading artists (Julio González, Alberto Sánchez, José Gutiérrez Solana, Horacio Ferrer, and many others), photomural panels (coordinated by Josep Renau), and displays that featured explanatory texts about the country’s regions, the ambitious reforms of the Second Republic, and the violent Civil War that had emerged following the military coup led by General Francisco Franco.

Critics and scholars over the past eighty years—2017 marks the Pavilion’s eightieth anniversary—have meticulously studied the Spanish Pavilion and the contributions by the numerous artists included there; the works by Picasso, Miró, and Calder have received the lion’s share of their attention.[5]

Within the space of this brief essay, little could be added to this extensive bibliographic record. However, there are some aspects of their work together, and the means through which their work carried political meaning and contributed to the economics of the fight against fascism, that merit further comment. For all three artists, the Spanish Republican Pavilion marked an important occasion in the evolution of their work. With Guernica, Picasso demonstrated the riveting outcome of applying the tools of Cubism on a monumental scale to the devastating theme of the Nazi blanket bombing of the historic Basque town of Gernika. Miró brought his tense and brutal exploration of realism and abstraction to the shouting, primary colors of his mural-sized rendition of a peasant holding up a defiant clenched fist in support of the Republic. And Calder fused the spatial command of his stabiles (as witnessed by his Devil Fish of that year) with the tensile sway of his mobiles, when he wrote in bronze the word “Almaden” to hang above the mercury stream that rolled and pooled down his bold swaths of black painted steel. In each work, a clear, if enigmatic, iconographic element anchored the artist’s experimentation and gave viewers a foothold in the present wartime drama: the bombing of Gernika, a single heroic peasant, and the vulnerability of the Republic’s most important mercury mine. While providing a reference to “the real,” each artist also pushed visitors to see beyond the icon by challenging them to move around the work, engage as active viewers in the problematic space of form and politics, and open themselves to the possibilities of the dynamic viewing space of the Pavilion, where scale and sense, recognition and absence, pushed against each other, often uncomfortably.

Though their resulting contributions were very different, the triangulation of their work in the Pavilion launched a powerful statement about the role of a new kind of pictorial intervention, one that was not “in the service” of a single ideology or artistic style, but rather responsive to the artists’ meditation on the cost of war and the character needed to survive it: fortitude and strength but also grace, dexterity, and nuance. The work of all three artists sought to avoid political platitudes through a direct appeal to what Cunard had labeled inter-boundedness, a sense of the artists and the work belonging to each other, and deeply connected to a space that they shared with the viewer. However, I would go even further than Cunard to suggest that the play among these three artists, and their interest in creating new forms to communicate the relation between artist and history, and artwork and community were staged first, not in Paris, but in Barcelona a few years before the Pavilion’s opening. Even more surprising might be the realization that, while the idea of inter-boundedness is relevant to the potential of their works to function politically (because inter-boundedness signals not just the relationship among the works, but also between the works and their makers), the political work that these artists were able to set in motion through their participation in the Pavilion was guided by something altogether different: a recognition of not only the role of the audience (as the third spoke of that inter-bounded relationship), but the power of commerce in the capacity of modern art to make a difference in the political effects of war.

While the Pavilion brought Calder, Picasso, and Miró into a shared exhibition space, during the 1930s their work was already jointly appreciated in Barcelona. It was seen as embodying the complexities of modern art within the context of the reformist climate of Spain’s Second Republic, which experienced a particularly sharp articulation in Barcelona. All three artists were featured in exhibitions and events held in the Catalan capital and sponsored by the newly formed organization Amics de l’Art Nou (Friends of New Art), or ADLAN. Following the declaration of the Second Republic in 1931, Barcelona’s cultural élite embraced the opportunity to launch new initiatives around art and urbanism, and some of the members of ADLAN were also affiliated with the architectural collective GATCPAC (Grup d’Arquitectes i Tècnics Catalans per al Progrés de l’Arquitectura Contemporània), the Group of Catalan Architects and Technicians for the Progress of Contemporary Architecture, formed in 1930 as the Barcelona branch of the national organization GATEPAC. Indeed, one of the foremost promoters of both ADLAN and GATCPAC was Sert, whose role in bringing Picasso, Miró, and Calder into the Pavilion is by now legendary. Sert’s understanding of the role that modern art played on the international stage, and its potential to be mobilized for the Republican cause, was unmatched among his Catalan peers. Because he held a lead role in organizing the Pavilion, he was in a key position to bring the lessons learned from Barcelona (especially in negotiating resistance to new art among the city’s cultural élite) to the Republic’s wartime project in Paris. The Pavilion also required a quick and efficient plan of action for high visibility and effective political persuasion, with a very compressed timeline from conception to execution.

A brief overview of ADLAN shows how important these artists were to its calendar of activities, and how their work announced the blend of progressive modern art and popular spectacle that became a hallmark of the group’s exhibitions and invitation-only events. ADLAN was formed in 1932. Its first sponsored exhibition was of Miró in November of that year, and several other exhibitions of his work were presented in the years that followed. In February 1933, ADLAN supported the performance of the “Circ Calder,” Calder’s circus, at the Galeries Syra. In January 1936, ADLAN organized the first exhibition of Picasso’s work in Spain since the turn of the century,[6] which opened in Barcelona at the Sala Esteva and then traveled to Madrid and Tenerife. All of their exhibitions were featured in the local press, and stood as signature events within ADLAN’s broad spectrum of activities.

Despite the infamous name that Carles Sindreu had first wanted to bestow on the group—“El Club dels Esnobs,” or the Snobs Club—the array of performers, artists, and events hosted by ADLAN demonstrates a commitment to breaking down the inherited hierarchies that separated popular art and entertainment from the gallery-based work of the avant-garde. The manifesto issued by ADLAN shortly after it launched made the group’s embrace of all forms of new art part of its guiding principals: “ADLAN calls you to protect and to encourage all enterprises of risk accompanied by a desire to excel.”[7] Open-mindedness, respect for the new, and a resistance to dogma and partisanship were the group’s headlining ideas. They ensured that ADLAN included artists who were well-known in the city by that time (such as Miró and Picasso) along with young and foreign artists (Calder). They also ensured a composite of events that ranged from lectures and classical music concerts to circus performers and Flamenco dancers, often staged as one-night-only affairs. The group combined a fascination for the ephemeral with landmark exhibitions that sought to write anew the history of the avant-garde as an integral part of the history of Barcelona. ADLAN’s beautifully designed invitation cards have become historical proof that there was a community coalescing around the presence of modern art in Barcelona. But it was undoubtedly one that was highly circumscribed, intentionally courted, and of very brief duration.

What was forged through ADLAN’s activities and its embrace of all three artists, who would later reunite in the Pavilion, was a desire to bring the latest work of modern art to the attention of the Catalan élite. These efforts were furthered (and documented) in the special December 1934 issue of the Barcelona-based illustrated magazine D’ací i d’allà (From Here and from There) that was dedicated to the art of the twentieth century. It was co-edited by Joan Prats, a leading member of ADLAN, collector of modern art, and good friend of Miró and Sert, and was billed as a collaboration between the two groups, ADLAN and GATCPAC. Throughout the issue, emphasis was placed on bringing order to the perceived chaos of modern art. Artists as diverse as Georges Braque, Jacques Lipchitz, Fernand Léger, Theo van Doesburg, Man Ray, Salvador Dalí, Le Corbusier, and Francis Picabia were marshaled to demonstrate to readers that, despite the differences among artists and their styles, it was possible to understand new art as an embrace of youthfulness, openness, and inclusivity. Indeed, the message repeated over and over was one of harmony and order. The issue’s editorial, written by Carles Soldevila, insisted on making sense of the latest challenges to tradition by grounding an appreciation for the present in the past. Miró dominated the content of the issue with numerous reproductions and critical praise of his work, and it was Miró who was featured on the issue’s cover. Picasso too was featured prominently throughout the issue, laying the foundation for what would become Sert’s push for an exhibition of his work in Barcelona a few years later. Although Calder did not receive a dedicated review, he was included in Sebastià Gasch’s chronicle of “Avant-garde Art in Barcelona,” and Gasch would continue to recall in his writings the impact of the “American Calder” on the Barcelona art scene.

However interesting it may be on its own, what relevance does this special issue of D’ací i d’allà and the work of ADLAN in Barcelona have in thinking through the work of the Pavilion in relation to the artistic aims of Picasso, Miró, and Calder in 1937? It is one thing to consider the push to promote new art in Barcelona before the war, and quite another to understand the challenges of staging new art as a force against fascism in Paris a few years later. I would argue that these two goals were historically interwoven, and that the challenges in creating a context and organization for modern art in Barcelona were actually quite similar to introducing it within the context of the Pavilion—and that in both cases it was Sert who pushed for, and facilitated, the idea that modern art and architecture were not simply the decorative flourishes of a politically conscious modernity. Rather, they were the cornerstones for a defense of modernity that allowed for experimentation and diversity in the arts as a fundamental component for political reform and democracy, even if these depended upon the support of the élite for their construction. Indeed, understanding the relation between the promotion of modern art and the defense against fascism as it was staged in the Pavilion requires us to think differently about reception and the conversion of artistic ideas into political, artistic, and economic currency. In Barcelona, there was not universal praise or acceptance for the work of ADLAN (or even Picasso’s exhibition in 1936); similarly, in Paris there was not an overwhelming consensus about what kind of art should be placed within the Pavilion or act as propaganda for the cause of the Republic. However, in both contexts there appeared to be a recognition that getting the support of the élite was important and that this could be done, at least in part, by enlisting the work of modern artists to create messages of support for the Republic on the global stage. To do so depended mightily on the ability and willingness of artists like Picasso, Miró, and Calder to understand the value of their own labor (process) and experimentation (form) as the necessary, if as yet unwritten, ingredients in Sert’s plan for the Pavilion’s maximum impact in Paris.

As part of his “How to Look” series for the independent PM New York Daily, in January 1947, Ad Reinhardt published an installment about “How to Look at a Mural,” which dissected for his readers the composition, symbols, and meaning of Picasso’s Guernica. Elsewhere I have studied Reinhardt’s observations on the similarity between Picasso’s mural and its “photo-montage-like” quality,[8] but for the purpose of this essay I draw attention to the equivalence that Reinhardt makes between the high quality of Picasso’s work and the revenue it brought to the Republican cause: “The mural (12 x 26 feet) represented the Spanish Loyalist Government at the Paris World’s Fair (1937), later toured London and America’s seven largest cities, was seen by over a million people, raised over $10,000 here to save many Spanish lives, and may be now seen at the Museum of Modern Art.”[9] Reinhardt’s summary description is all about dimensions, scale, and impact: monumental size, high viewership, and large revenue stream. Coming as it does, in a daily that prided itself on being free of advertising and funded entirely by its readers, his attention to the mural’s economic work on behalf of the Spanish Republic is noteworthy, since the money raised is not garnered through commercial exploitation or branding. He makes a point of reminding viewers that Picasso’s painting is unlike “a simple poster or banal political cartoon that you can easily understand (and forget) in a few minutes.” Publicity and propaganda are banal, easy expressions, whereas the hard work and difficulty of perception brought forward by Picasso in Guernica merit Reinhardt’s full praise.

The idea that labor, scale, and conversion into currency should signal Picasso’s work as a successful example of the pairing of art and politics with fundraising should return us to the Pavilion’s preparations with an eye toward understanding how Picasso, Miró, and Calder may have also envisioned their contributions to the cause. The documentation of the labor involved in the making of their works, combined with the artists’ other contributions to the Pavilion’s contents, makes for a powerful insight into how the three artists were able to work independently while also creating other purpose-specific designs in which their prestige directly benefitted the Spanish Republic. In the descriptions of their work for the Pavilion, and in the documentation produced by the artists or collected afterwards, their labor and the actions they took to produce their work on grand scale in a short period of time have become an integral component to the history (and mythology) of their participation in the Pavilion. It is also in their conversion of creativity into currency, I would argue, that Picasso, Miró, and Calder moved outside the discourse of politics and form, and into a more firmly grounded commitment to the economic cost of war. The contributions of all three artists extended beyond the limits of the Exposition Internationale in Paris.

In contemporary and retrospective accounts of their work for the Pavilion, time and again we see an emphasis on process and labor becoming the legitimating discourse for political commitment. At the time many of these accounts were photographed or written, they would not have formed part of the historical reception of the work. But they have since become integral parts of the biographies of the artists and the reconstruction of the pre-history of the works that were displayed in the Pavilion. In the case of Picasso, it was Dora Maar’s photographs that chronicled the evolution of Guernica and demonstrated the artist’s dedication to working through the variations in composition, form, and colors for his painting. We see less documentation of the installation of the mural in-situ, as the painting was completed before being transferred to the site. For Miró, we see in photographs the artist standing on the wooden scaffold perched in front of the monumental expanse of Celotex surface that lined the stairwell’s vertiginous expanse.

The head of the Catalan peasant is larger than Miró’s body, and implicit in the picture is the risk and effort involved in the work of painting the mural on location. Unlike Miró and Picasso—who were commissioned to make their works months before the Pavilion opened—Calder was invited by Sert to design and fabricate the Mercury Fountain as a last-minute substitution for the original plan of bringing a fountain from Spain. Sert recounted that Calder pieced together a model version that he tried out on the street before completing the design. By the time he was ready to install the fountain in the Pavilion, Guernica was in place. Photographs from the period show Picasso and Calder talking beside his fountain, with Picasso’s painting in the process of being hung on the wall behind. There to examine the placement of his work, Picasso arrives in a suit; photographs of Calder and Miró show them with their sleeves rolled up, in the midst of either painting (Miró) or installing (Calder). They have converted the Pavilion into an ad hoc studio.

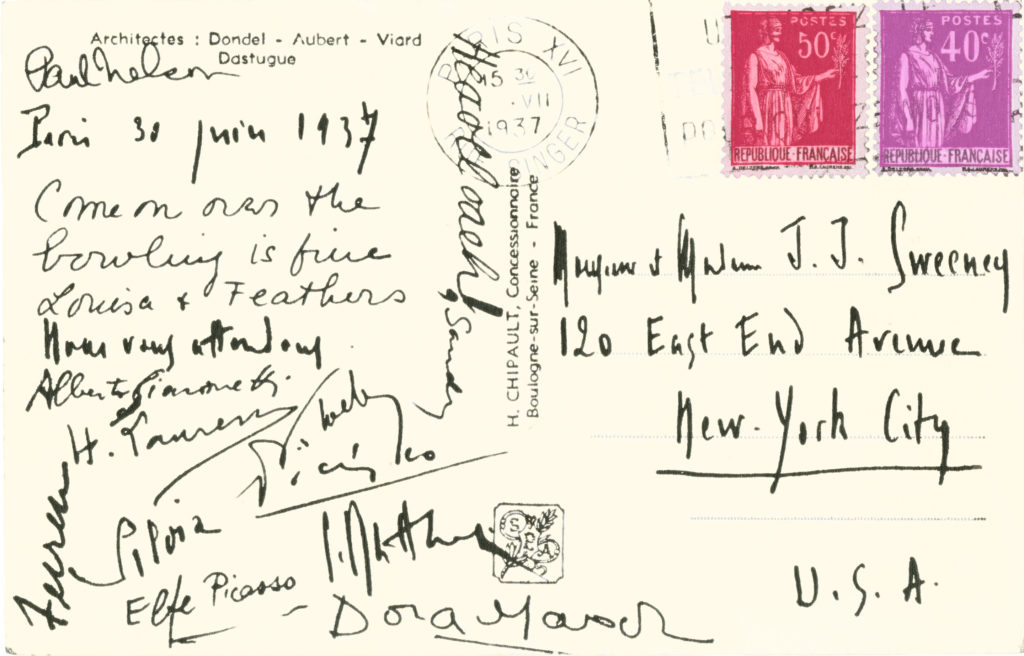

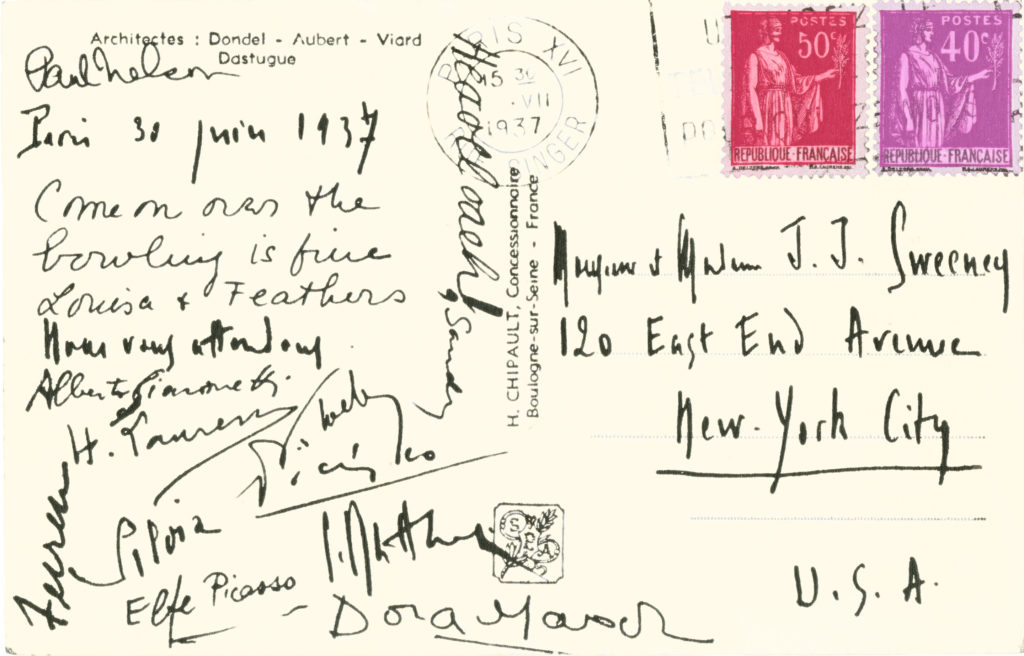

Throughout the run of the Pavilion, the work of all three artists generated money for the Republic in quite direct ways. While their presence raised the profile of the Pavilion and certainly attracted the attention of artists, writers, and critics, both Miró and Picasso also contributed prints that sold at the Pavilion. Within the Pavilion a kiosk was set up in which merchandise could be purchased to benefit the Spanish Republic. On sale were prints, postcards, magazines, and other objects produced or published by the different political organizations involved with the Pavilion, including most visibly the Comissariat de Propaganda, the Catalan government’s propaganda agency, and the state government’s propaganda ministry. The head of the Comissariat de Propaganda was an intellectual named Jaume Miravitlles, who had been a childhood friend of Salvador Dalí, and had spent the years of the dictatorship of General Miguel Primo de Rivera in exile in Paris. He was a leftist political organizer who worked on the committee for “L’Olimpiada Popular,” or the People’s Olympics in Barcelona, which were to be held to protest the official Olympic games in Nazi Germany. The military coup broke out in Barcelona on the day the games were scheduled to open, and Miravitlles’s skills were deployed instead to lead the Comissariat when it was officially established a few months later in October 1936. He named Pere Català-Pic, a leading photographer and promoter of the use of modern technology in publicity, as his head of publications. The philosophy around art and propaganda held by the Comissariat was deeply informed by the practices rehearsed in Barcelona throughout the 1930s in magazines like D’ací i d’allà. Too, the model for packaging, and enticing attendees to buy into, a vision of Spanish reform based on principals of visual modernity must have been influenced by Sert’s role in directing the Pavilion.[10] What was placed in the vitrines and displayed for sale was most probably not an ad hoc array but a highly deliberate selection, with work by Picasso and Miró garnering significant attention.

The works by Picasso and Miró that were offered for sale at the Pavilion intersect with the multimodal approach that the Comissariat and other political agencies took toward the publication and promotion of propaganda during the Civil War, in that they were works of high recognition and value that were crafted in dialogue with cheaper modes of distribution for mass culture. As Miriam Basilio has summarized in her analysis of the iconography in Picasso’s Dream and Lie of Franco: “We know that the work was sold as two sheets with a portfolio cover designed by the artist, with a poem also by him, in an edition of 1,000, but some authors state that postcards were also sold to benefit the Republic at the Pavilion.”[11] Citing the scholarship of Patricia Failing and others, Basilio remarks that the design of the prints themselves reference the dimensions of postcards and the possibility that the “etchings were designed for reproduction as sets of postcards … ” brings Picasso’s portfolio into dialogue with the mass circulation of propaganda on postcards during the war. Similarly, Miró’s pochoir Aidez l’Espagne, which was also on sale at the Pavilion, had initially been designed as a 1-franc stamp at the suggestion of Christian Zervos. Robert Lubar has recounted at length the importance of this stamp design to Miró’s easel painting Still Life with Old Shoe and his Pavilion mural The Reaper, while advocating for a contextual understanding of Miró’s artistic response to the Civil War.[12] He reminds us that the original stamp design, while reproduced in the last issue of the GATCPAC magazine A.C. in 1937, was never published for purchase; it was in the form of the retitled and resized pochoir that Miró’s original idea went on sale. What the research of both Basilio and Lubar teaches us is that the higher-end versions of Picasso’s and Miró’s designs offered for sale at the Pavilion included within their material history cheaper versions that would have been accessible to a broad public, with the potential for circulation among a wider array of more cheaply produced propaganda. What also becomes apparent is that their monumental, in-situ works, whose stories of process and labor I discussed earlier, might have been made more personal—the distance between viewer and artist shortened—by the simultaneous display and sale of their etchings and pochoirs in the Pavilion kiosk.

Like Picasso and Miró, Calder would also design posters to benefit those who had supported the Republic during the war; in fact, throughout their lives all three artists contributed designs for posters that raised funds and awareness for a variety of causes. In May 1937, William Crookston, Executive Secretary of the North American Committee to Aid Spanish Democracy, wrote to Calder about an exhibition of Spanish posters to be held at the Delphic Studios gallery in Manhattan in June and July of that year, requesting permission to use Calder’s name as one of the sponsors—since, as Crookston noted, he was a “member of our Artists and Writers Committee.”[13] Interestingly, this request would have come to Calder around the time Sert approached him about designing the fountain for the Pavilion after initially rebuffing his request to participate. (Sert was at first reluctant to commission anything from Calder because he was a foreigner.) Though they have not attracted the same attention—nor, one might argue, do they hold the same iconographic density as the contributions by Miró and Picasso to the Pavilion’s kiosk—the lithographs that Calder donated in the 1960s and 1970s to benefit Spanish Refugee Aid (SRA) raised hundreds of thousands of dollars for the organization.[14] In contrast to Miró and Picasso, however, in the Pavilion itself the conversion of his work into currency did not transpire in two separate precincts, the main exhibition area and the kiosk. Instead, Calder’s Mercury Fountain directly enticed visitors to contribute money. In an essay for the Stevens Indicator in 1938, Calder recalled: “The fountain proved quite a success, but a great deal was due, of course, to the curious quality of the mercury, whose density induced people to throw coins upon its surface, and often three hundred francs were taken in a day in this manner, for the benefit of the Spanish children.” Though he credited the fountain’s success to the material itself, an argument could be made that it was Calder’s design that transformed visitors’ curiosity into funds for the Republic.

1947 was a pivotal year in writing the history of the Spanish Republican Pavilion, as it marked the ten-year anniversary of Guernica as well as offering a moment of reflection following World War II. On the occasion of his publication of Juan Larrea’s Guernica, Pablo Picasso that year, Calder presented Curt Valentin with a beautiful, calligram-like iron memento that joined the horizontal writing of the word Guernica to the vertically scripted Picasso, with the three colors of the Republican flag tied in velvet at the top. When installed near Guernica at the Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía, it effectively collapses the temporal distance between 1937 and 1947 and brings together Dora Maar’s photographs of the painting-in-process with the writing of its historiography a decade later. Indeed, 1947 was also a vital year in the critical reception of the work that Picasso and Calder contributed to the Pavilion. Cunard’s brief but energetic praise of Calder’s exhibit in Paris appeared the same year that the Museum of Modern Art in New York held its symposium on Guernica to mark the work’s tenth anniversary. Reinhardt’s response in PM, which bridged the erudite world of the museum and the popular culture of the street, also demonstrated the insight of one artist to another: as he heaped praise on Picasso, he also pointed out the demands that the artist made on his viewers, as well as Picasso’s response to interrogations about his own politics. In a side note, Reinhardt brought together the Spanish Civil War and World War II recounting: “A story tells how a Nazi official who, looking at a photograph of this mural, remarked to Picasso, ‘So, it was you who did this,’ received the answer, ‘No, you did.’”

Placing blame where it belonged and contributing time and labor to benefit those directly impacted by war were objectives shared by all three artists. At the same time, defending the space of artistic play, ambiguity, and experimentation were high priorities. In the Pavilion, with Sert’s support and encouragement, all three were called upon to imagine works that might challenge visitors while enticing them to see themselves as connected to the Republican cause. Going back to Cunard’s notion of inter-boundedness with which I started this essay, I would argue that Sert was pushing for an elevated notion of interconnectedness between artist and public—one that could be parsed between prints and objects that might be acquired relatively cheaply, and work in-situ that required greater attention, patience, and commitment. By calling on visitors to pause and connect, to respond to the violence and shock of war with complementary forms of attention, Picasso, Calder, and Miró were asking viewers to shift from the accelerated pace of wartime propaganda (made, of necessity, for instant recognition and reaction) to a different form of sensory engagement. We know from the criticism at the time that not all visitors or critics responded favorably to this invitation, but we also know that these artists knew enough to pair their artistic experiments with other forms of exchange, placing their one-of-a-kind works alongside other designs that traveled the circuits of popular culture, raising awareness and funds much more fluidly, contributing massive sums to the work of agencies in support of the Republic, and later the war’s refugees. In offering complexity as a response to war, they also incited generations of artists, critics, and historians to contemplate the weight and responsibility of the role of the artist in wartime. These three individuals clearly understood that the hard-won prestige they had acquired through their work as modern artists could also be a tool through which to convert artistic designs into currency for a cause.

Hauser & Wirth, Somerset, England. Calder: From the Stony River to the Sky. Exhibition catalogue. 2018.

Susan Braeuer Dam, For the Open Air

Jessica Holmes, More than Beautiful: Politics and Ritual in Calder’s Domestic Items

Solo Exhibition Catalogue“Calder in France.” Cahiers d’Art, no. 1 (2015). Edited by Alexander S. C. Rower.

Susan Braeuer Dam, Calder in France

Robert Melvin Rubin, An Architecture of Making: Saché and Roxbury

Agnès Varda in conversation with Joan Simon

Magazine, MonographMuseo Jumex, Mexico City. Calder: Discipline of the Dance. Exhibition catalogue. 2015.

Alexander S. C. Rower, Calder: Discipline of the Dance

Solo Exhibition CatalogueMusée Picasso, Paris. Calder-Picasso. Exhibition catalogue. 2019.

Bernard Ruiz-Picasso and Alexander S. C. Rower, Confronting the Void

Chus Martinez, No Feeling Is Final

Group Exhibition Catalogue