So once on board the De Grasse, I started walking the deck. I overtook an elderly man and a young lady. I could only see them from the back, so I reversed my steps the better to see them face on. Upon coming abreast of them the next time around, I said, “Good evening!” And the man said to his daughter, “There is one of them already!”

He was Edward Holton James, my future father-in-law.

She was Louisa.

Her father had just taken her to Europe to mix with the young intellectual elite. All she met were concierges, doormen, cab drivers—and finally me.[1]

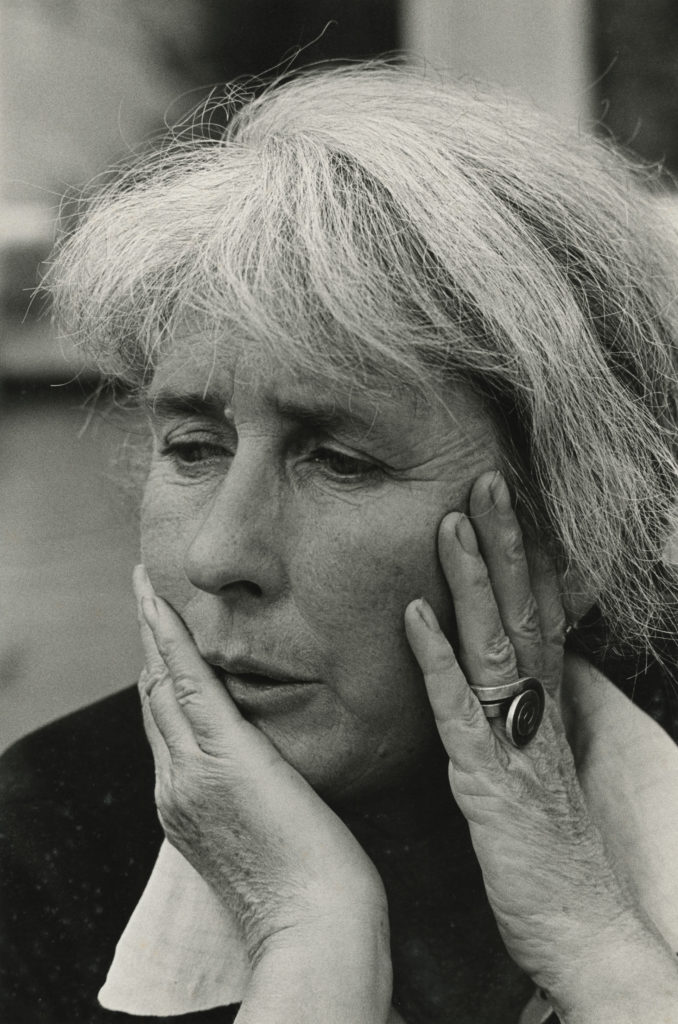

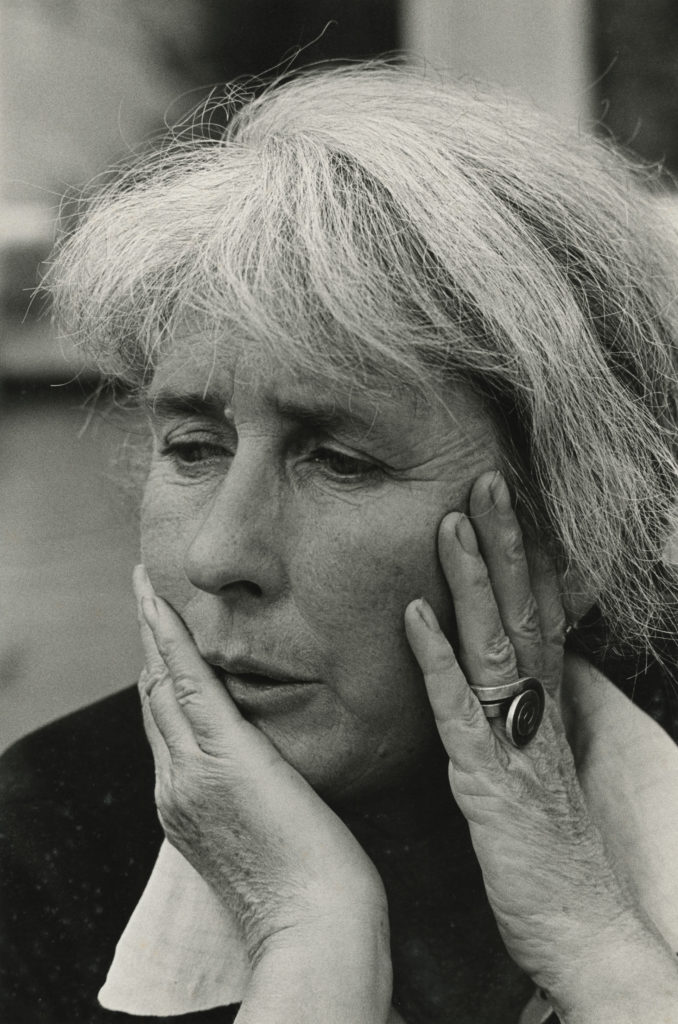

Soon after their chance encounter aboard the De Grasse Louisa James received a bracelet made from a continuous brass wire hammered flat spelling out “Medusa.” My grandfather nicknamed her “Medusa” because of the wild ringleted hair she could not tame on board the ship.[2]

Born into an intellectual family, Louisa was brought up in proper Boston society by an English nurse and a French governess. Her parents were outwardly conformist (he a James and she a Cushing),[3] though her father was a Quixotic fighter for social justice.[4] In 1930, Louisa wrote to her mother:

To me Sandy is a real person which seems to be a rare thing. He appreciates and enjoys the things in life that most people haven’t the sense even to notice … He has tremendous originality, imagination and humor which appeal to me very much and which make life colorful and worthwhile.[5]

That year, Calder made her an engagement ring:

I had known a little jeweler in Paris, Bucci, and he had helped me make a gold ring—forerunner of an array of family jewelry—with a spiral on top and a helix for the finger. I thought this would do for a wedding ring. But Louisa merely called this one her ‘engagement ring’ and we had to … purchase a wedding ring for two dollars.[6]

After their marriage in 1931, Louisa became less concerned with social conventions and lived a simple bohemian life with Calder. He would often observe her at work making bread or hooking rugs and go out to the studio to devise a tool to simplify her task. He made hundreds of gifts for her: sculptures, drawings, household inventions, and untold numbers of jewelry that she wore in her daily life. Many of them were created for a specific garment: buttons for a certain coat, a buckle for her black wool cape, etc. As seen in this photograph by Herbert Matter (c. 1942), her dressing bureau was a very private moment in their home where Louisa displayed her Calder jewelry along with an ode to Calder’s studio by André Masson. When I was a child, her bureau always seemed a mysterious altar to me.

The following pages illustrate Calder’s devotion to Louisa through a selection of jewelry he made for her spanning their life together. Many were inscribed for wedding anniversaries (17 January), birthdays (19 February), and other memorable occasions …

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. Calder Jewelry. 8 December 2008–1 March 2009. Originated from the Norton Museum of Art, West Palm Beach, Florida.

Solo ExhibitionHauser & Wirth, Somerset, England. Calder: From the Stony River to the Sky. Exhibition catalogue. 2018.

Susan Braeuer Dam, For the Open Air

Jessica Holmes, More than Beautiful: Politics and Ritual in Calder’s Domestic Items

Solo Exhibition Catalogue“Calder in France.” Cahiers d’Art, no. 1 (2015). Edited by Alexander S. C. Rower.

Susan Braeuer Dam, Calder in France

Robert Melvin Rubin, An Architecture of Making: Saché and Roxbury

Agnès Varda in conversation with Joan Simon

Magazine, MonographMuseo Jumex, Mexico City. Calder: Discipline of the Dance. Exhibition catalogue. 2015.

Alexander S. C. Rower, Calder: Discipline of the Dance

Solo Exhibition CatalogueMusée Picasso, Paris. Calder-Picasso. Exhibition catalogue. 2019.

Bernard Ruiz-Picasso and Alexander S. C. Rower, Confronting the Void

Chus Martinez, No Feeling Is Final

Group Exhibition Catalogue