The scholar of mythologies Georges Dumézil used to say: “it is only by comparing something to something else that we can truly know it.” The comparison of Calder’s work, not merely to his contemporaries, but to generations of artists that followed him, enables us to truly decipher what is idiosyncratic about his practice. The comparative effect may well be designed to find commonalities, but it also allows to identify what is truly specific—what Calder does that, say, contemporaries or friends such as Julio González or Marcel Duchamp did not do. Seeing Calder’s work in the company of diverse artists from the years 2010, 2020, and beyond makes it possible to trace back reverse genealogies. We can figure three deeply interconnected traits in particular that manifest Calder’s uniqueness, while being in clear conversation with the work of contemporary artists. The first is the issue of monumentality, and its challenges. The second is the genesis of forms. The third is the matter of pictoriality within sculpture. All together, they enable us to uncover the metaphysical, aesthetic, and philosophical issues at hand both in Calder’s work and across contemporary practices.

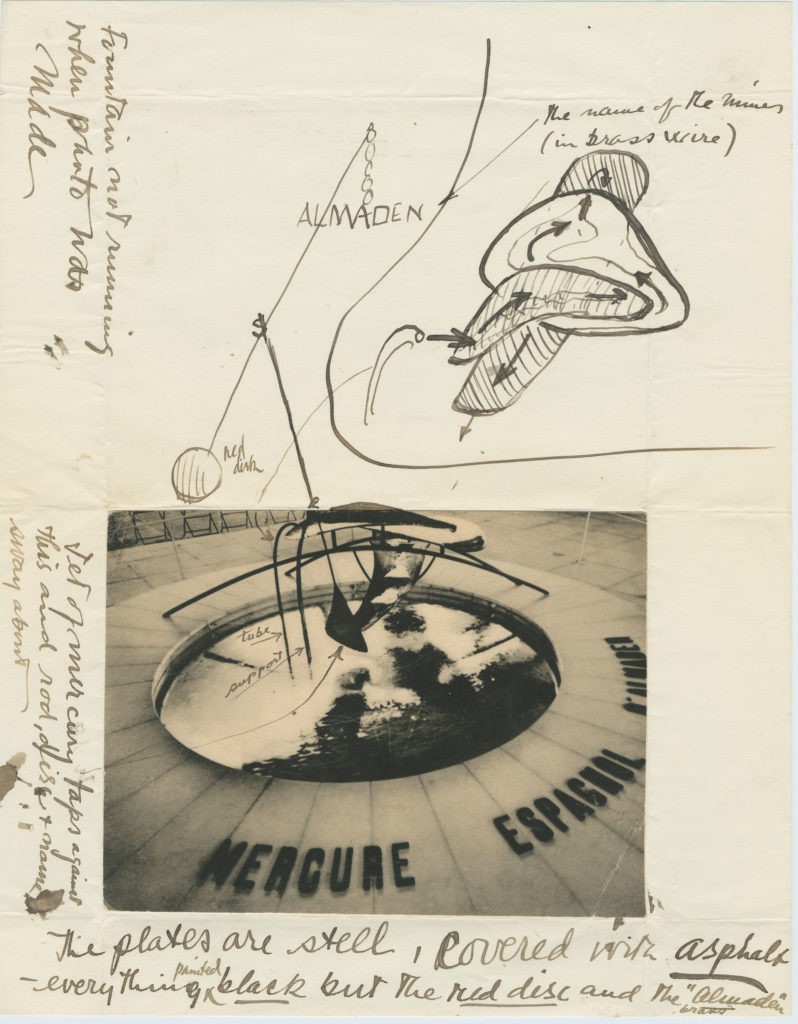

Calder was fond of monuments. He famously conceived his Mercury Fountain for the Spanish Pavilion at the 1937 Paris World’s Fair and was commissioned to create a Water Ballet for the Consolidated Edison Pavilion at the 1939 New York World’s Fair, and many of his late sculptures have in fact a monumental scale. His frequent use of thick steel is testament to his desire to play with the characteristics of a monument: its durability, its outdoor existence, and therefore vulnerability to changes in weather conditions, its presence in the public space, its relation to an event. A monument is erected to commemorate a glorious event. Calder did not shy away from such proposals—which already at the time of the European avant-gardes may have come across as dated. Picasso, for example, was not a frequent nor passionate practitioner of sculptural monuments. The only well-known examples are Picasso’s attempt to build a monument for his friend Guillaume Apollinaire—and, to an extent, the sculpture he made for the Daley Plaza in Chicago. Calder’s interest in monuments was less personal, less marked, more closely related to external events. Another example would be Brâncuși’s scale. And yet, Brâncuși did not aim to celebrate, commemorate, or mark anything. His sculptures were at a monumental scale but did not perform the act of the monument.

Calder made monuments and monumental sculptures that inhabited public spaces. However, he did not conceive them to mark political events—as there had been a tradition in Western culture—but activist events, such as the aforementioned Spanish Pavilion at the Paris World’s Fair, in favor of the Spanish Republic, or commercial events like the New York World’s Fair. In doing so, he was bringing a form of fluidity within the hierarchical, political European construction of the monument. Even in monumental scales, he worked as much on the negative space as on the positive space of the sculpture. In fact, it is with wire that Calder began experimenting with scale. As he wrote in January–February 1929, “These recent things have been viewed from a more objective angle and although their present size is diminutive, I feel that there is no limitation to the scale to which they can be enlarged.”[1] This ambivalence brings us to a key tension in Calder’s work: while he made monumental works—and works as monuments—he played against the very grain of monumentality. In that way, he was close to Picasso, whose initial Project for a Monument to Guillaume Apollinaire (1928) was entirely made of wire, therefore making it a fragile monument—much like Calder’s wire sculptures (of a larger scale) from the same period. Calder’s work performs anti-monumentality even in the works that seem most monumental. The early large-scale wire works from 1928—Hercules and Lion, Spring, and Romulus and Remus—all have mythological and antique themes, as if to manifest the tension between the ancient monument and the modern material.

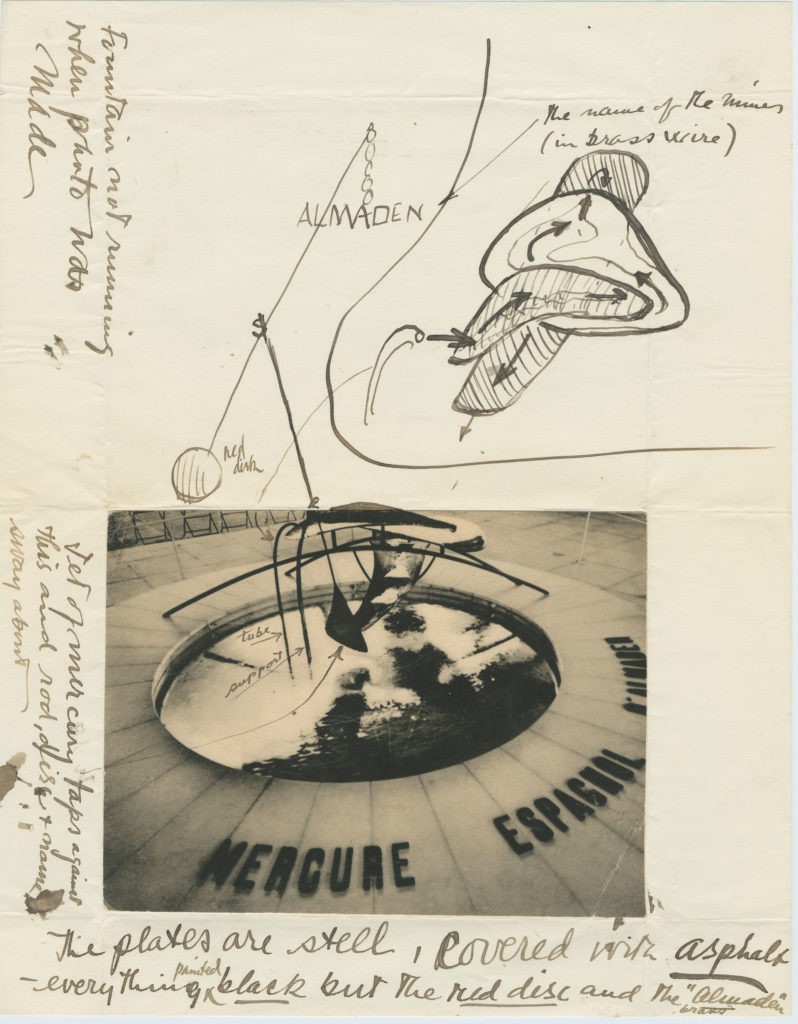

He often experimented in different scales and media: his many choreographic sketches of the Water Ballet for the 1939 New York World’s Fair paved the way for the reality to be. Each of them is a scene, and an extremely ephemeral one at last. His version of the monument confronts and includes fragility. It defuses and confronts narrativity. A key aspect of Calder’s work is the refusal of the narrative factor that stands at the very core of any monument: they tell us what to think, who to believe, to admire and to follow. There is no lesson to be drawn from Calder’s work, who in that regard was—as Duchamp—a follower of Stéphane Mallarmé’s famous phrase, “suggestion is the dream.”

Calder turned our preconceptions upside down, while bringing a form of monumentality within his most apparently fragile works—the mobiles. There are large-scale mobiles which are as fragile as they are monumental. The preconceived idea according to which monumentality meant forever-durability and encompassed a political message is therefore outdated. He brings the monumental within a space of acceptance of fragility and in fact makes this very fragility into an asset for the monumental. Fragility is no longer a denial of the monumental: it opens the possibility for another, more active monumentality.

Alongside durability, the monumental relied on stability. The very premise of Calder’s work is instability, or rather a form of fluidity, lability: the fact that sculptures can become a perpetuum mobile, can go from a short, tight gesture into extreme action. The hand of a human being can shake it and bring it into action. Calder opened up a completely new approach to sculpture. He included aspects of what had been monumental—scale, material—and brought it into a conversation with what appeared to be the opposite: fragile materials (wire, for example); smaller scale; labile structures. He created a space in which these apparent contradictions could coexist and allow for a larger, more open experience of sculpture.

This still feels incredibly relevant. There had not been many artists pre-Calder who were willing to assume together both the monumental and the anti-monumental: they had chosen one way or the other. Even Miró, whose paintings, to an extent, assume both the discreet and the continuous, diverge from the effect of his sculptures, which do not rely on such a tension. Calder performed it to the end, going bigger and bigger, even in his last works, as well as bringing his own sculptures into a space unknown to sculpturality: the space of monumental lability.

As much as Jackson Pollock’s pictorial gestures and the overall dynamic of Abstract Expressionism, this is a key to understanding Land art and Minimalism—movements from the 1960s and 1970s—and has significant politically critical undertones. Calder challenges the very notion of the imposition of a narrative-filled monument into the land: he immediately places it within the relativity of time and space. As much as with the notion of site-specificity—which entertains a complex relation to sculpture at once limiting and foundational—Earth art has to do with the interaction between the variation of scales and the play with monumentality. What may come across as monumental may only be a “scar in the landscape,” as Michael Heizer famously described City, his masterpiece anchored in the deserts of Nevada. Calder accomplished the very gesture of unanchoring monumentality from the premise of a large scale. This gesture has exerted a considerable influence on any sculpture that followed him: it is not—as, for example, it was the case with Auguste Rodin—that there could be several sizes for a same work, often related to commercial purposes. After all, Rodin’s sculptures entered many bourgeois houses in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, thanks to their smaller-scale renditions. Despite his frequent working within a smaller scale, Calder’s gesture is inherently different: it relies on a question of what monumentality can be, and how it can or cannot be connected to scale. To manifest monumentality without losing oneself in the mere parameter of scale, Calder included complexity and the variety of materials. A monument was no longer to be a simple form—however idealistic such an approach may have been—it could in fact blend different forms, materials, into one experience.

Such a reflection on what comprises monumentality also found its way into Earth art, and installation as well. The monumental is by definition architectural: it is embedded within spaces housing humans. Sculpture is defined as a reality in itself, while a monument exists mostly with and from its interactions with the public space around it. Calder included interactions with the public in his work, which may come across as one of the premises of what an installation can be: it is a web of relations to the world that is both inside and outside of it. The more performative the installation may be, the more it could confront the very logic of monumentality. However, when artists achieve the realization of a moveable monument, a monument that would at once be physically anchored and could change, shift, then a radical dimension of art finds itself unleashed. The work exists on its own—as a sculpture—but it can also be activated—as a performative installation. It is the case, for example, with Untitled (c. 1947), a reflecting standing mobile of sheet metal, rod, and wire, with two tin cans in which candles are placed and lit, entirely changing the experience of a sculpture that is durable—albeit fragile—but which changes all the time as the candles burn.

Many installations play with the notion of sculpturality. As physical entities inhabiting a space, they are sculptures. As disseminations, they are installations. Michael Fried’s definition of theatricality—the very definition that made installation art possible theoretically—is very potent to describe Calder’s work: it opens up its own space as a stage and the space around it as a contaminated stage as well. One may think of Duchamp’s Étant donnés as an early installation, too, and of many of Duchamp’s works as precursors to the history of the installation. Duchamp moved into another space, while Calder remained in many ways a classical sculptor. Such is his role in the history of art: he manifested that sculpture could coexist with a much freer approach to art-making; that the move toward the installation did not have to be a contradiction to the more traditional approach to sculpture—even with what had become the tradition of modern art. Calder is a modern artist who marks the end of the straight lineage known as modernism and opens it up to a multiplicity of forms and existences.

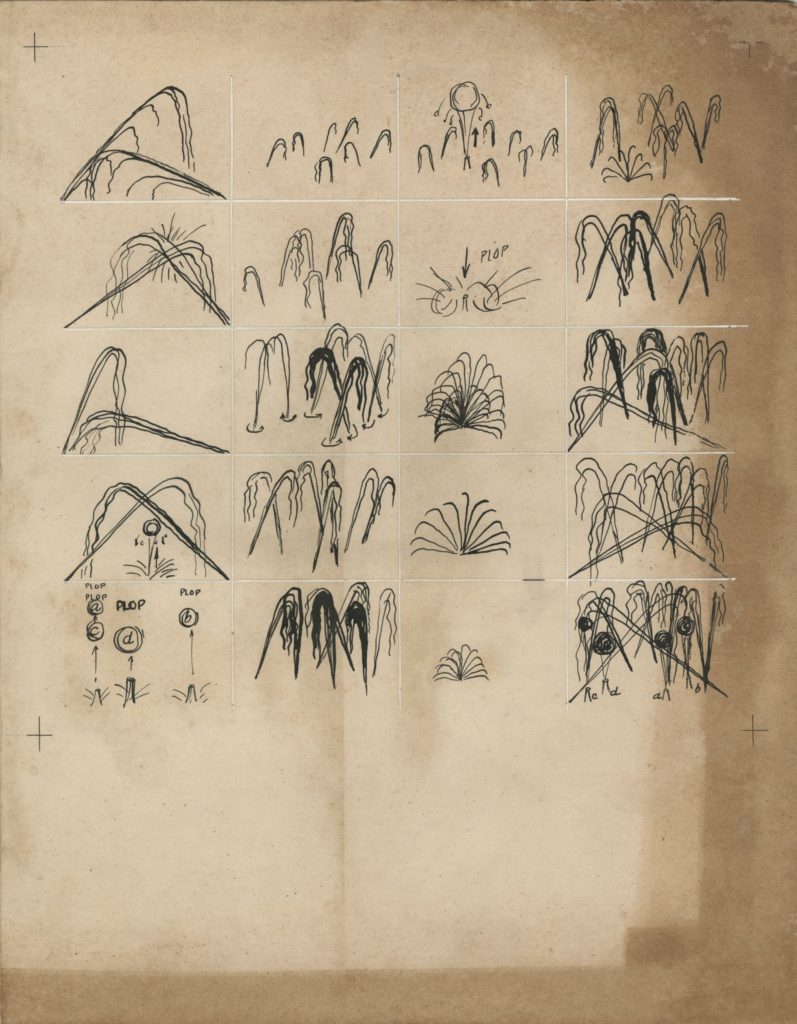

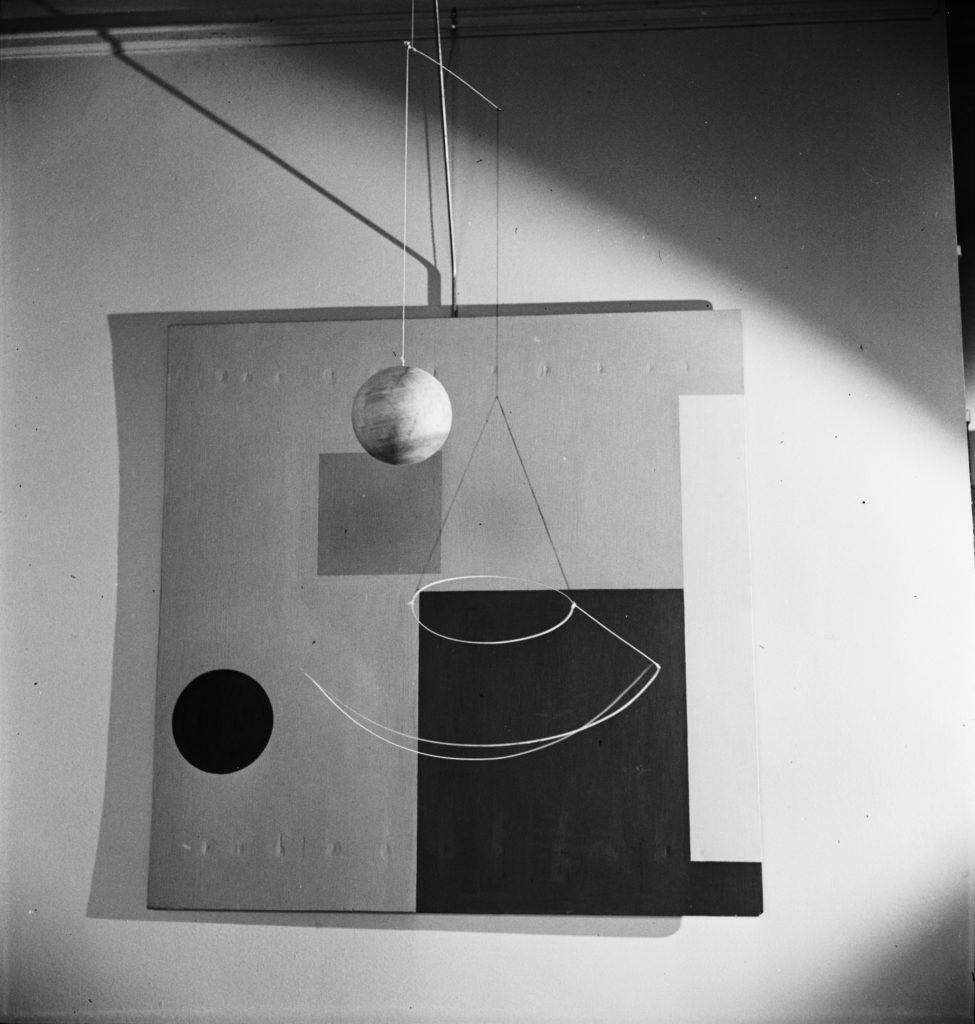

This is a second contemporary lesson that might be drawn from Calder’s work. Calder moved away from modernism’s theosophic passion for geometric shapes—spheres, squares, triangles—to make forms flexible: to draw in space. Each form of Calder’s is distinctive, but its forming is entirely free from the limitations of referentiality. A form is a form and it is itself as a form. Therefore, he moves away from modernism’s attempt to understand the world through geometry—the Platonist drive of modern art—to propose a consideration that would be entirely form-based, but whose forms would be consistently open. As such, he invents a way of making art with and through forms without actually being formal. His use of form is a statement for freedom, rather than constraint. In the same way as Calder did not shy away from sculpturality while making works that changed radically the very fabric of the sculptural method, he also included round shapes in his works. But those very round shapes at times were not perfect, not entirely geometrical. With Untitled (1937), he used squares and circles, but he played with optics: we are not entirely certain of what we see, of the perception of the shapes, of the perspective. It is their imperfection that marks their status as forms, sculptures. These presences reminiscent of geometry are only a section of his work: they cohere with vegetal forms—petals, branches—apparently human forms. And yet they are not limited to a motif, an origin: they are displaced from those motifs and origins, to enter another space where they are mere forms, without any limitation to geometry.

Calder’s stance is close to Henri Focillon’s classic 1934 text, The Life of Forms. Focillon studied Platonic forms across cultures. Calder goes one step farther and attempts to create forms that would not be limited to one situation, to one culture or system. Calder’s forms may be connected to genesis of modernism, to certain works by Wassily Kandinsky, to some of his contemporaries. And yet they exist entirely on their own. Their “predecessors” could be found in Mesoamerican cultures as well as in the Cyclades; they defuse any attempt at localization. This is another major contribution of Calder’s: he created a postcultural sculptural language, in a way that no one had done before. This is the reason why his impact can be found in many contemporary practices, and not merely, say, in White American sculpture. He embraced the shift in which art was about to engage in his days: the shift from the local, the domination of Western culture, and the embrace of other cultures as serving this very Western culture, toward a new form of art—one that is not designed to take, but to serve and engage audiences from anywhere.

Calder may be a household name, but his works are as challenging today as they ever were: how are we to understand Calder? Should we understand his work in the way we always wanted to understand art, and somehow still learn from it? Or should we just accept that he has created forms for us to experience—to enjoy, if we want to use a Pop American term—or to participate in, if we want to enter a sublime experience both modern and atemporal? These are lessons that so much participatory art has manifested—art that questions its existence in separation from the world—in profound connection with it.

Calder entered this new time, ushering in an era of post-monumental, post-geometric, post-hermeneutic art. But he did that while still being a painter. This might be the last note on which to end these brief remarks. Calder brought polychromy into painting; polychromy was considered almost a folk-art creation, when he brought it into his art. Even sculptors like Hans Bellmer or Edgar Degas, when they made use of polychromy in their works, were accomplishing radical gestures that questioned taste. Sculpture, in order to be a post-Neoclassical/Romantic art form, had to be white—or, when in bronze, dark golden. At times, Calder used unpainted sheet metal, but he opened up the forms of sculpture to include painted metal: red, blue, yellow, there were no colors that could be forbidden to him. The purer the color, the stronger the effect. As he used those colors, he was no longer part of a discussion on folk art: he updated the very language of what had become modern art. He understood that colors in sculpture were not merely decorative—they activate what Calder called “differentiation”: when monochrome (at least on one segment of a sculpture), they activate different experiences—deeper experiences. This is a lesson learned across contemporary practices: the classical modern separation between painting and sculpture—a separation that finds itself in the very name of the chief curatorial department of the Museum of Modern Art—may no longer be relevant. Sculptures play with colors; paintings open up their forms. As new generations of artists experiment, across the world, with the potentialities of color, sculpture, painting, form, they are continuing the legacy of Alexander Calder: as an artist, he was a formidable bridge who closed an era by opening up a new one. In doing so, he was an impeccably original visionary.

Kunsthal Rotterdam, Netherlands. Calder Now. 21 November 2021–29 May 2022.

Group ExhibitionHauser & Wirth, Somerset, England. Calder: From the Stony River to the Sky. Exhibition catalogue. 2018.

Susan Braeuer Dam, For the Open Air

Jessica Holmes, More than Beautiful: Politics and Ritual in Calder’s Domestic Items

Solo Exhibition Catalogue“Calder in France.” Cahiers d’Art, no. 1 (2015). Edited by Alexander S. C. Rower.

Susan Braeuer Dam, Calder in France

Robert Melvin Rubin, An Architecture of Making: Saché and Roxbury

Agnès Varda in conversation with Joan Simon

Magazine, MonographMuseo Jumex, Mexico City. Calder: Discipline of the Dance. Exhibition catalogue. 2015.

Alexander S. C. Rower, Calder: Discipline of the Dance

Solo Exhibition CatalogueMusée Picasso, Paris. Calder-Picasso. Exhibition catalogue. 2019.

Bernard Ruiz-Picasso and Alexander S. C. Rower, Confronting the Void

Chus Martinez, No Feeling Is Final

Group Exhibition Catalogue