Pure experience is … the immediate flux of life which furnishes the material to our later reflection with its conceptual categories … a that which is not yet any definite what, tho’ ready to be all sorts of whats; full both of oneness and of manyness, but in respects that don’t appear; changing throughout, yet so confusedly that its phases interpenetrate and no points, either of distinction or of identity, can be caught.

–William James[1]

Over the course of his decades-long career as one of the most innovative artists of the twentieth century, Alexander Calder remained largely uninterested in commentary, allowing his work to speak for itself. He used the non-art term “object” instead of “sculpture” to describe his mobiles: “Then a guy can’t come along and say, no, those aren’t sculptures. It washes my hands of having to defend them!”[2] When he wrote or spoke about his objects, he often gave succinct answers that were open to interpretation. As for his intricate reflections, they were mostly given in the 1930s, a time when he perhaps did feel the need to “defend” his radical new works; even so, his words expressed infinitudes: “speeds, velocities, accelerations, forces, etc.”[3] He was not concerned with insightful titles, nor did he intend for a title to provide any fixed access to its object—an object that, fundamentally, was not even its own subject. “Didn’t use to name them at all, in the beginning,” he once quipped. “When I wanted to talk about one of them, I’d have to draw it.”[4] It comes as no surprise, then, that the term “mobile” was coined not by Calder but by his friend Marcel Duchamp. Replacing Calder’s “object,” the term “mobile” nonetheless lends insight into the artist’s sensibilities and predilections, all the while eluding categories and dissolving boundaries.

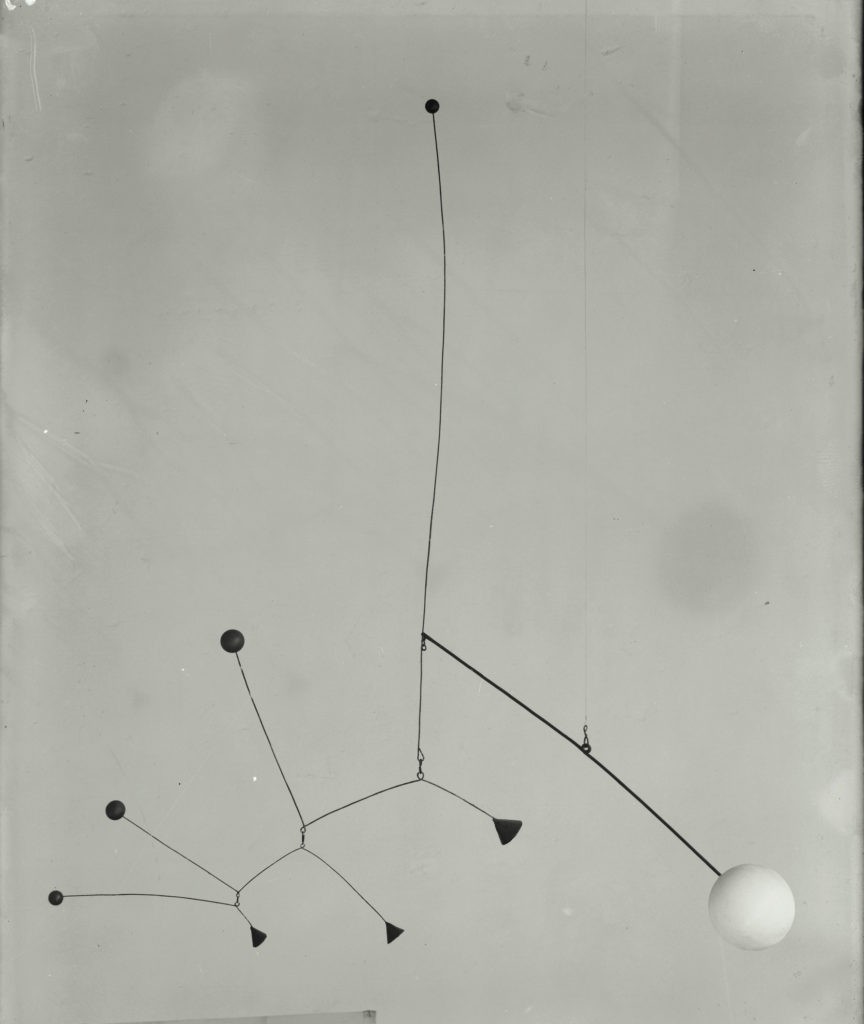

When thinking about Calder’s mobiles, what most often comes to mind are objects in sheet metal and wire suspended from the ceiling whose agile elements embody momentary flux and fluidities. Sculptures that, in the words of French existentialist Jean-Paul Sartre, are “always beginning over again, always new.”[5] But the work that prompted Duchamp to produce the term “mobile,” during what was his second visit to Calder’s Paris studio in 1931, was markedly different. As Calder recounts in his 1966 autobiography:

One evening, [Mary Reynolds] brought Marcel Duchamp to the rue de la Colonie, to see [Louisa Calder and me] and my work. There was one motor-driven thing, with three elements. The thing had just been painted and was not quite dry yet. Marcel said: “Do you mind?” When he put his hands on it, the object seemed to please him, so he arranged for me to show in Marie Cuttoli’s Galerie Vignon, close to the Madeleine. I asked him what sort of a name I could give these things and he at once produced “Mobile.” In addition to something that moves, in French it also means motive.[6]

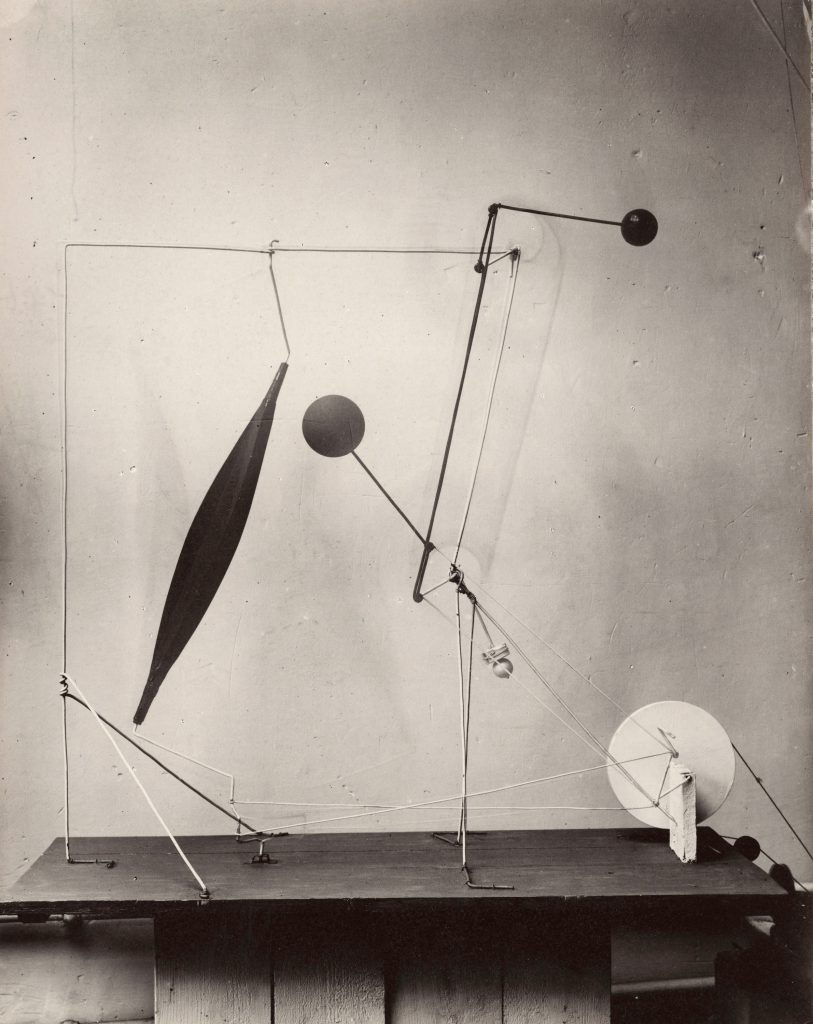

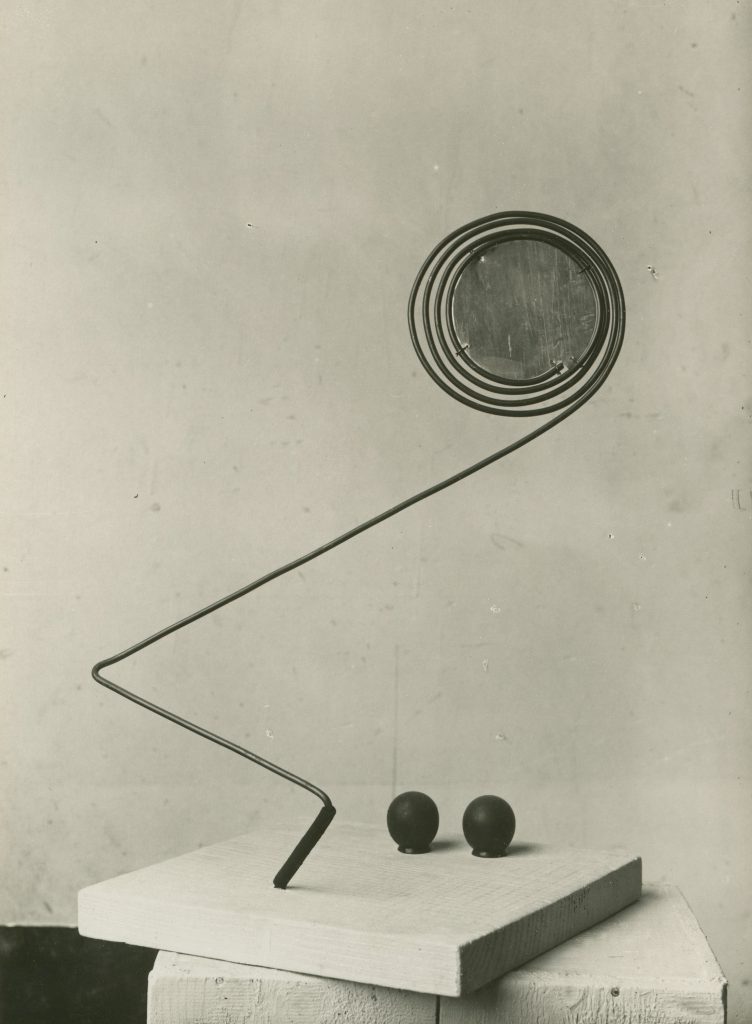

Although intimate in size, the motor-driven thing that enraptured Duchamp was grand in imaginative force. It was a type of mechanized composition that Calder originated in Paris and later referred to as a ballet object, a small-scale work whose elemental motions were bounded within the limits of a frame, panel, or massless cube—a form that today we categorize as a standing mobile.[7] These objects were revolutionary not only as sculptures that actualized movement as opposed to representing it, in the manner of the Cubists or Futurists, but also as models whose realizations within the proscenium arch of the theatrical stage—a performative concept envisioned by Calder as a ballet without dancers—signaled the dissolution of long-standing boundaries between painting, sculpture, choreography, musical composition, and theater. Even though their kinetics were predetermined, they nonetheless embodied aliveness, expressing life not as an uninterrupted flow but as a multivalent march, with its own idiosyncratic stops and starts, its own endings and beginnings.

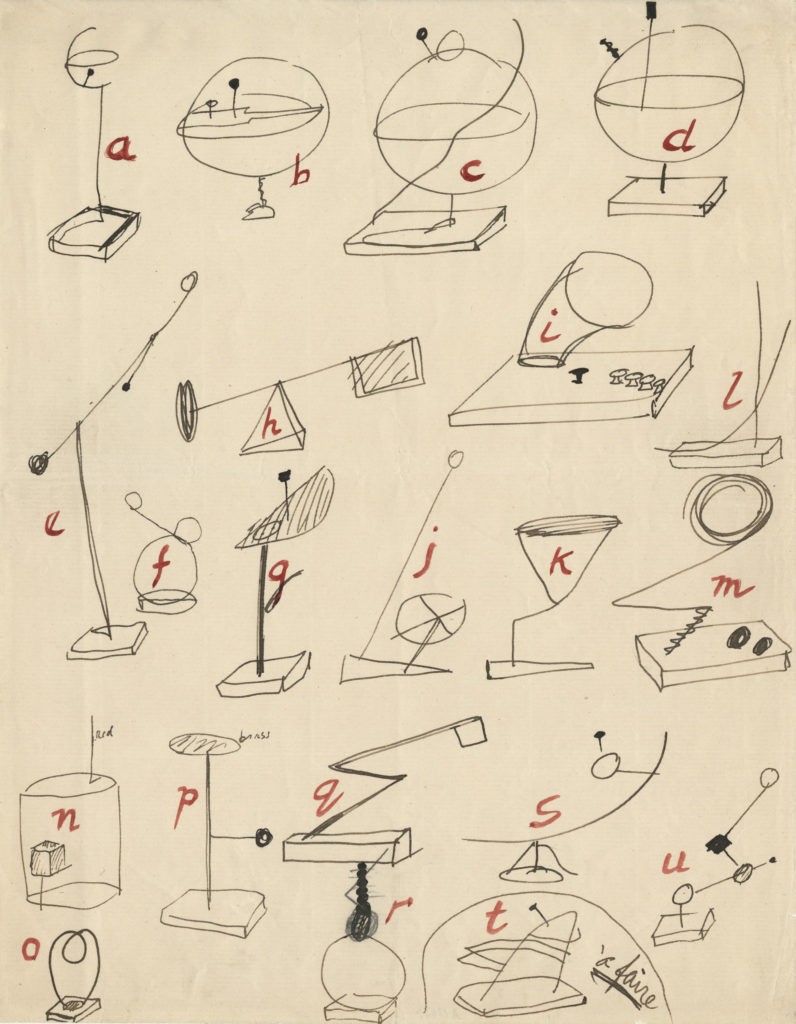

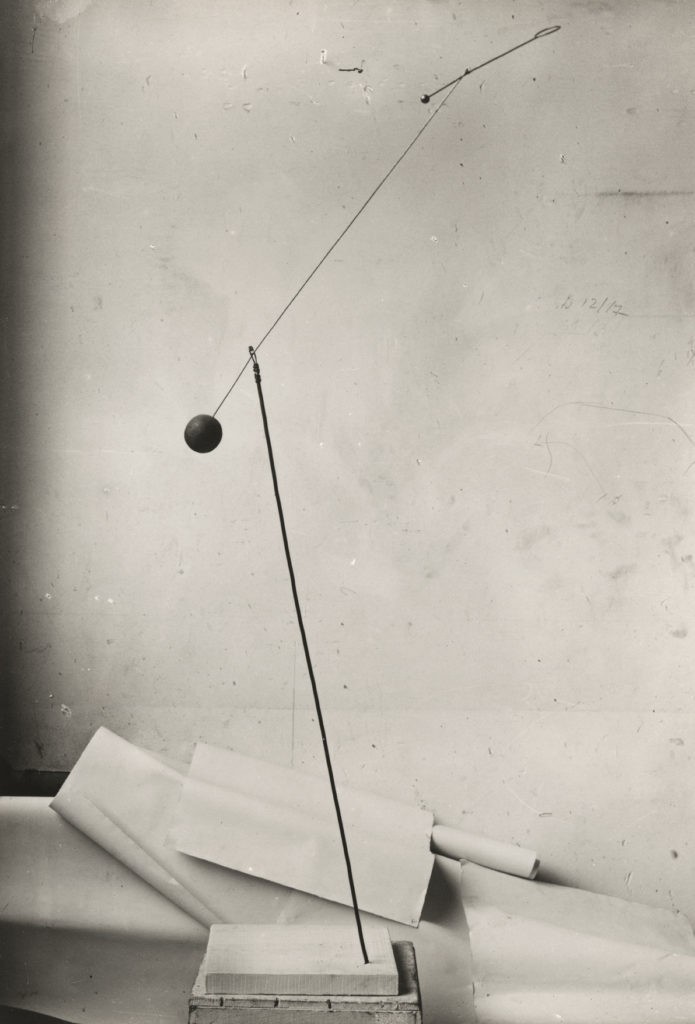

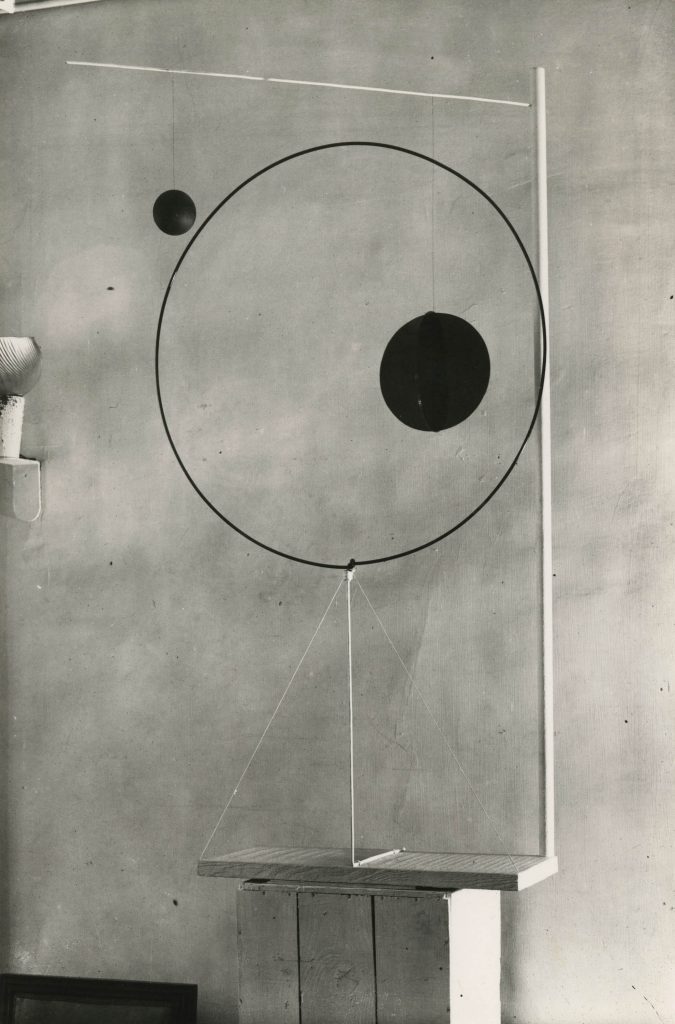

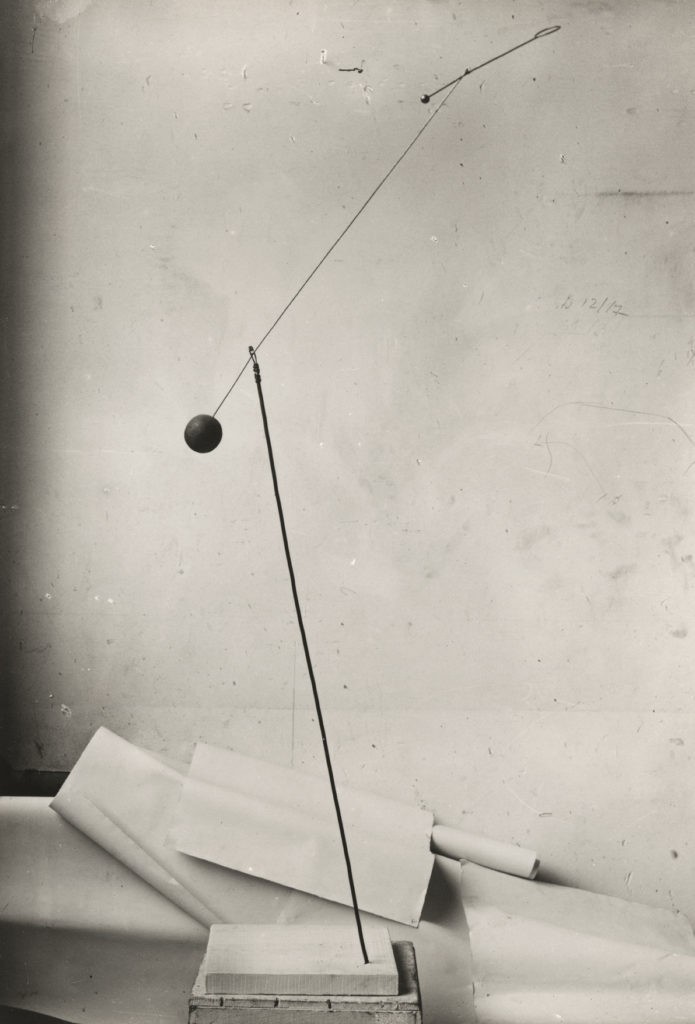

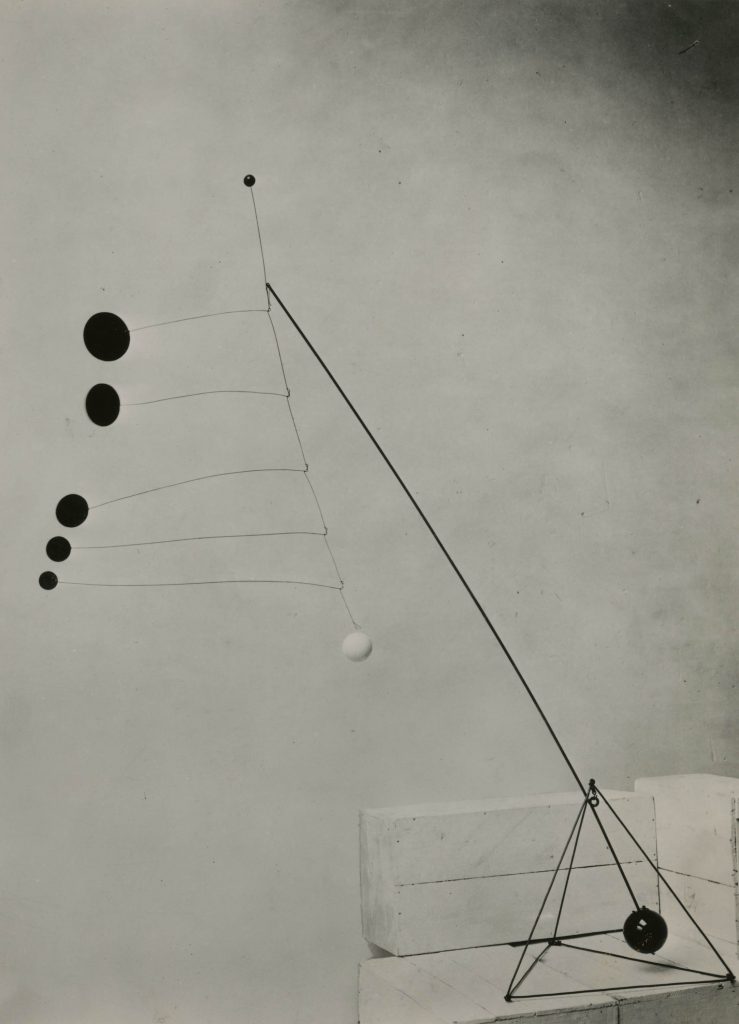

The motorized objects, however, were not Calder’s first standing mobiles. The spring before Duchamp’s fabled visit, Calder included “two slightly articulated objects that swayed in the breeze” in his premiere of nonobjective works at Galerie Percier in Paris, Alexandre Calder: Volumes–Vecteurs–Densités/Dessins–Portraits.[8] Circulation (1931) comprised a rod with a tin square on one end and an ebony form on the other that pivoted atop a massless tetrahedral wire base, and in Gémissement Oblique (1931), a nearly vertical rod supported not one but two mobile elements, punctuated by a brass sphere, an ebony sphere, and a wire loop. “I had made them thus because I felt that perhaps I wasn’t the final person to decide which was the absolute best position,” wrote Calder, a statement that not only signals a symbiotic sensibility, but also resonates with what he once described as an “admission of approximation,” or the difficulty of transmuting abstract intuitions into physical objects.[9] Their titles, the latter of which translates into “oblique groaning” or “oblique groan,” evoke passages or life forces as opposed to particular situations or fixed interpretations. Even the relatively static wire works that surrounded these two standing mobiles at Percier engaged multidimensional realms through inherently vibratory wire lines and light-reflecting elements, among them Croisière (1931), with its thick and thin wires expressing dynamic forces, and Musique de Varèse (c. 1931), its piece of unpainted tin engaging luminous energy.

According to Duchamp, “Calder’s approach to sculpture was so removed from the accepted formulas that he had to invent a new name for his forms in motion.”[10] Duchamp had employed the term “mobile” in an adjectival capacity in a series of notes written between 1912 and 1915 for a never-executed part of The Bride Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors, Even—also known as The Large Glass (1915– 23)—describing a “mobile Weight with nine holes,” a power system meant to activate the Chocolate Grinder (an element of the Bachelor Apparatus). But Duchamp’s selected notes were not published until 1934 in The Green Box, and by that time, the term “mobile” had already become widely associated with Calder, who had presented his kinetic objects on both sides of the Atlantic in solo and group shows alike, including a collection show at the Museum of Modern Art, New York—Alfred H. Barr Jr., having already acquired one for the museum. Interestingly, Duchamp chose the term “delay” instead of “picture or painting” to describe The Large Glass: “It’s merely a way of succeeding in no longer thinking that the thing in question is a picture—to make a delay of it in the most general way possible, not so much in the different meanings in which delay can be taken, but rather in their indecisive reunion.” In their essence (and in the seemingly endless scholarship on them), Duchamp’s notes for The Large Glass add up to what Calvin Tomkins surmised as an “open question”—just as the mobile, with its continual unfolding of complex interrelationships, evokes question upon question.[11]

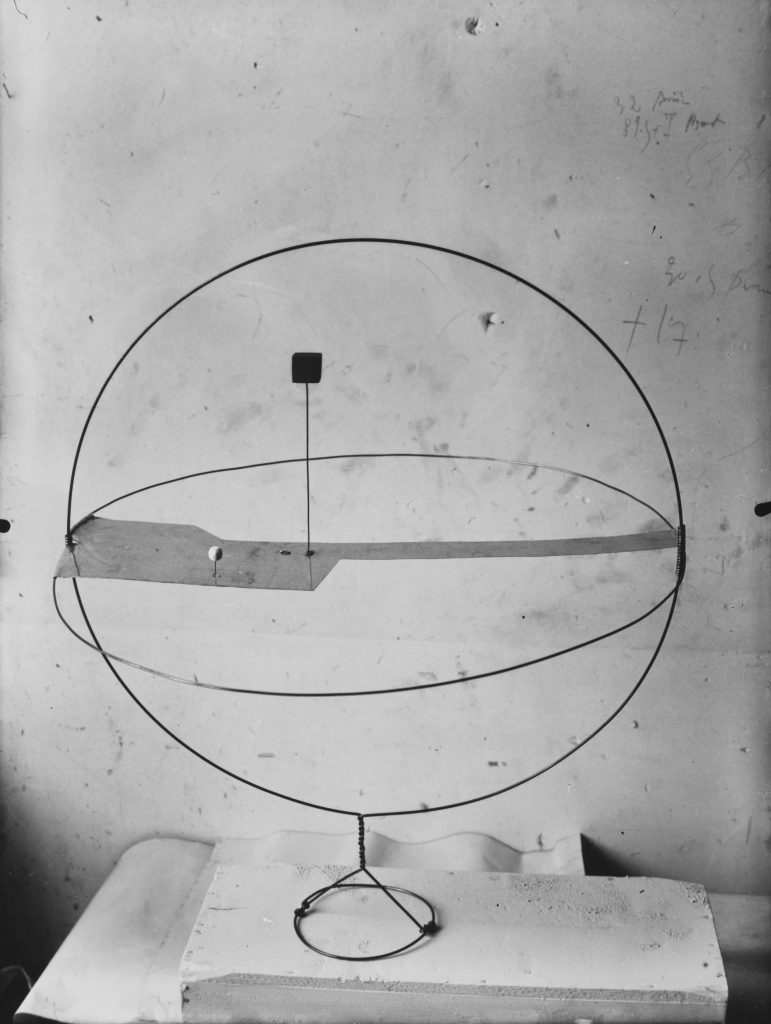

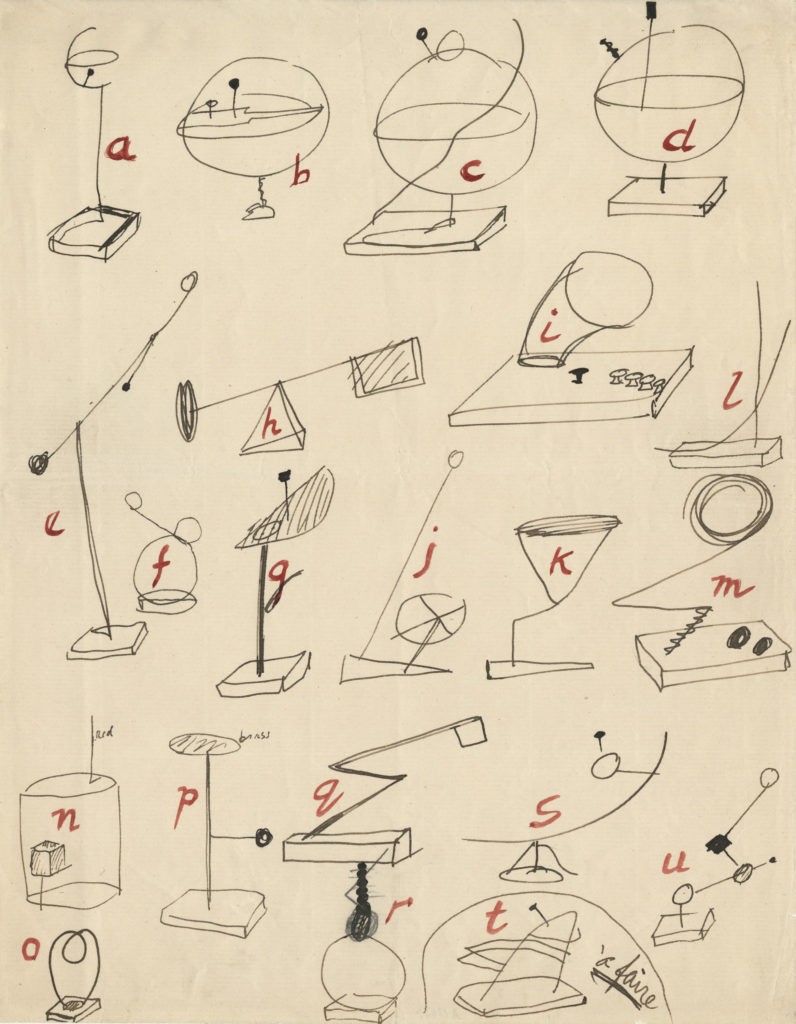

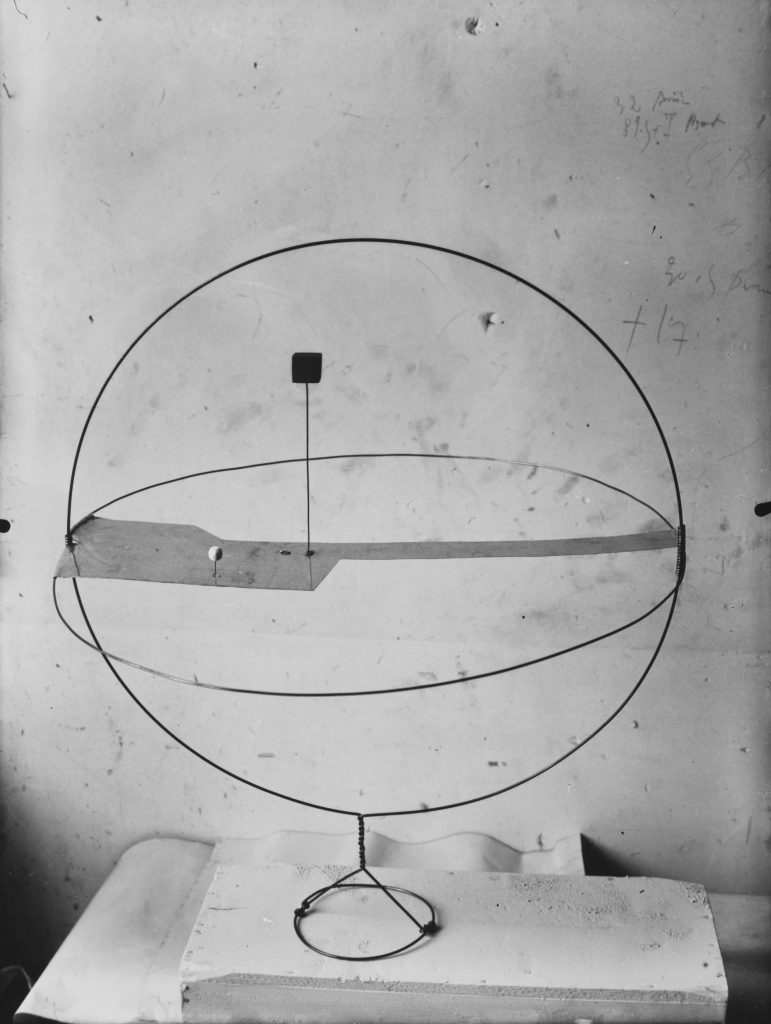

While motives and styles overlap and coexist in art-world praxis, what Calder was doing in Paris was a radical departure from that of his avant-garde contemporaries. Naum Gabo’s Kinetic Construction (Standing Wave, 1919–20), Aleksandr Rodchenko’s Spatial Construction no. 12 (c. 1920), and Man Ray’s intellectual stunt Obstruction (1920) all “tentatively introduced” motion into sculpture. But no artist embraced or formalized motion to the extent that Calder did in his kinetic works of 1931–32.[12] Through the use of cranks, gears, shafts, levers, belts, and cams in his motorized objects, he was able to create a diversity of movements in a single composition, or “several motions of different types, speeds and amplitudes composing to make a resultant whole”; and in those “slightly articulated” objects at Percier, he introduced the unpredictable, the evoked, the spontaneous into sculpture.[13] In 1931 alone, he expanded upon motion in numerous ways, including human intervention, as seen in the recomposable Object with Red Ball (1931) and the crankable Two Spheres Within a Sphere (1931).

The terms “object” and “mobile” carry their own nuances in resonance with Calder’s sensibility—or meanings of “indecisive reunion,” to draw upon Duchamp. The primary definition of the noun “object” in English is “something material that may be perceived by the senses,” and as a verb it connotes “to put forth in opposition or as an objection.”[14] Calder’s use of the term at once indicated an autonomous reality—not an abstraction of observable nature, but an embodiment of the nature of all things—and a radical break from (or opposition to) the tradition of sculpting in marble, bronze, and clay. By calling them “objects,” he was also naming what he was doing as something apart from sculpture—specifically the solid volumes produced by his father, Alexander Stirling Calder, and his grandfather, Alexander Milne Calder—reflecting his respect for what sculpture had always meant. As he once remarked to journalist William Rogers, “‘Objects’ refer to ‘sculpture which is not necessarily a marble figure of someone leaning his head on his hand.’”[15] Connections can also be drawn to the term’s implications in 1920s and ’30s Paris, a time when the Surrealists observed a talismanic power in objects. When The Exhibition of Surrealist Objects premiered at Galerie Charles Ratton in 1936, it featured one of Calder’s suspended mobiles made largely of glass fragments, or objets trouvés, which reflected and refracted the surrounding light—suggesting an art event, not merely an art object. Concurrent with the show, André Breton published his famed essay “The Crisis of the Object” in a special issue of Cahiers d’Art, revealing the world beyond the everyday object, presented anew.[16]

The term “mobile,” as an adjective in French, means “moving, movable, loose” or “darting, nimble, agile.” As a noun, it means a “motive” or “what prompted his action or crime.”[17] Calder, like Duchamp, appreciated the indeterminacy of the pun, and his unwillingness to cling to definitions reverberates with his unwillingness to be defined; throughout his career, he did not ally with the movements of the day, even though figures like Breton rallied behind him. Entries for the term “mobile” in Dictionnaire de l’Académie française from 1932—the year of the mobile’s debut—present a dizzying list of applications, ranging from military and physiognomic to mechanical and natural themes, including a reference to the surface of water; it also names the fête mobile, or holidays with changing dates.[18] A few of these definitions conjure the spirited imagery in Sartre’s seminal essay on Calder from 1946, in which he describes the mobile as “a little local fiesta” or “like the sea and equally spellbinding.”[19] In 1954, “mobile” appeared in the addenda section to the Second Edition of Webster’s New International Dictionary to describe Calder’s sculpture: “n. Art. A delicately balanced construction or sculpture of a type developed by Alexander Calder since 1930, usually with movable parts, which can be set in motion by currents of air or mechanically propelled.”[20] Calder’s work had become so integrated into the public domain that it gave rise to an entirely new genre whose definition continues to evolve (as all definitions do), transgressing boundaries in art, echoing the very adaptability and versatility manifest in sculptural form.

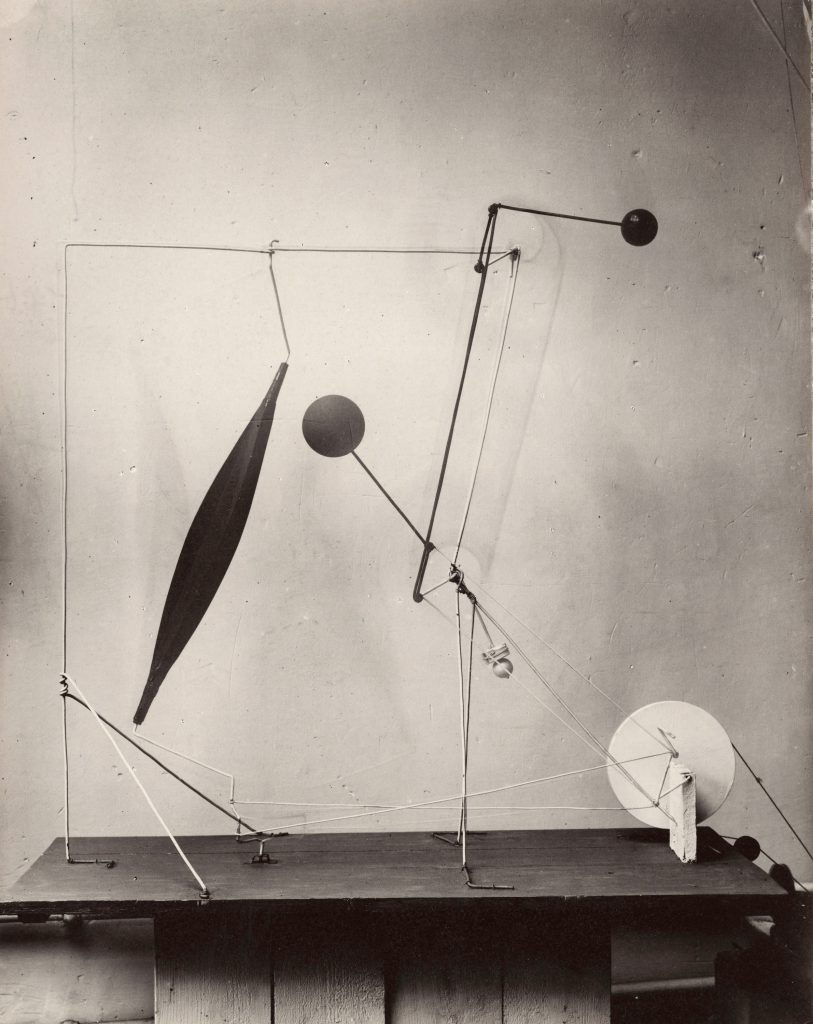

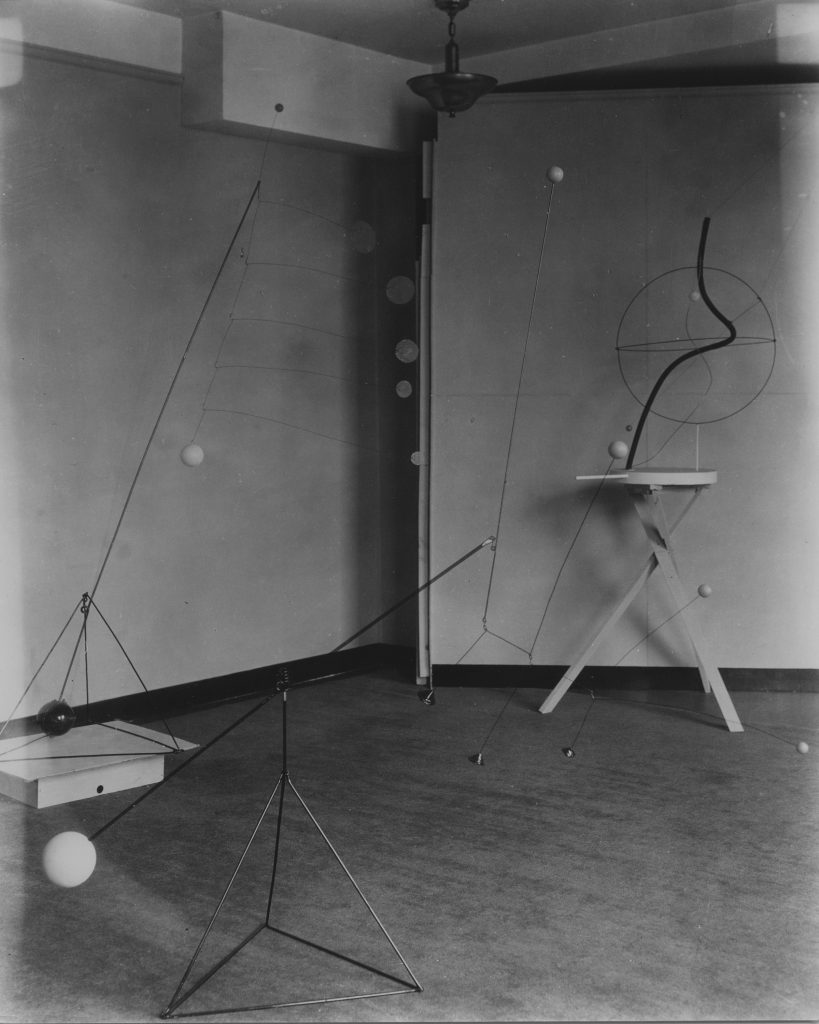

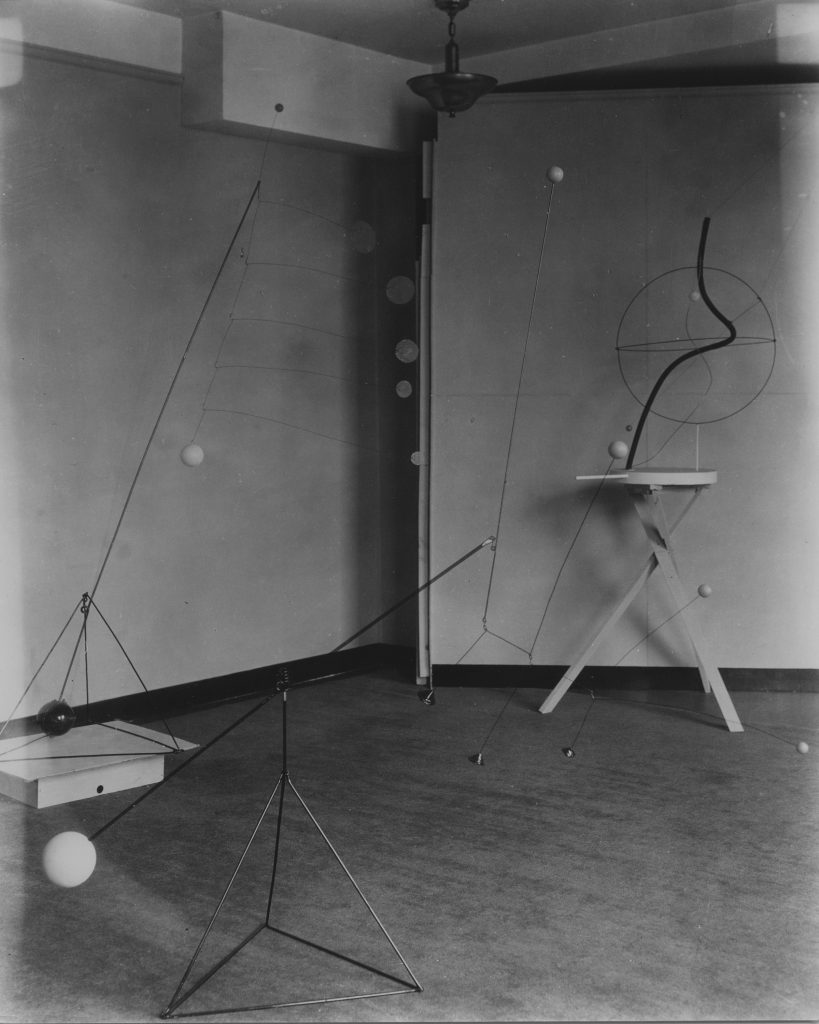

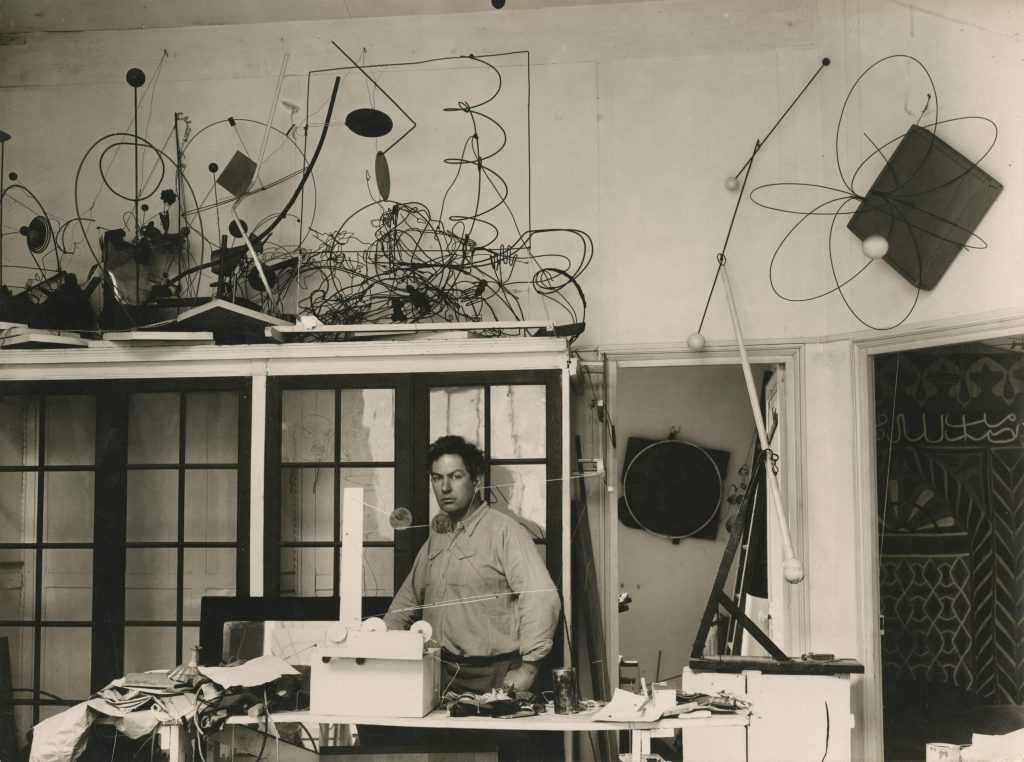

Photographer Marc Vaux’s image of Calder’s Paris studio from fall 1931 captures a pivotal moment in the artist’s trajectory, one that simultaneously attests to the nonlinear development of the mobile. (It also provides us with a comprehensive account of what Duchamp would have seen during his visit there.) In this photograph, Calder’s studio on the rue de la Colonie is in disarray, with wire sculptures from all periods coiled up into clusters, depicting a scene that contrasts greatly with the spare, massless, transparent objects for which the artist was known. Two vastly different 1930 portraits of French muse Kiki de Montparnasse can be observed, together representing Calder’s provocative shift, as if overnight, from figuration to abstraction: One of her wire portraits hangs within the vitrine (a proto-mobile with actual suspension), while his abstraction of her visage, Féminité, with its light-reflecting, radiant eye, can be seen protruding from atop, at left. Other works from Percier are situated around Féminité, including Circulation, and to the right is a tangle of Spring and Romulus and Remus (both 1928), the very two human-sized wire sculptures that prompted critic Paul Fierens in February 1929 to coin the term “drawing in space” when they premiered in Paris at the Grand Palais.[21] At the far right of the photograph is a large standing mobile whose form resembles that of Gémissement Oblique, the latter having been gifted by the artist to a museum in Lodz, Poland.[22] Front and center of it all is the thirty-three-year-old Calder, recently wed to Louisa James, and at his fingertips, the motorized work Pantograph (1931), soon to make its premiere at Galerie Vignon.

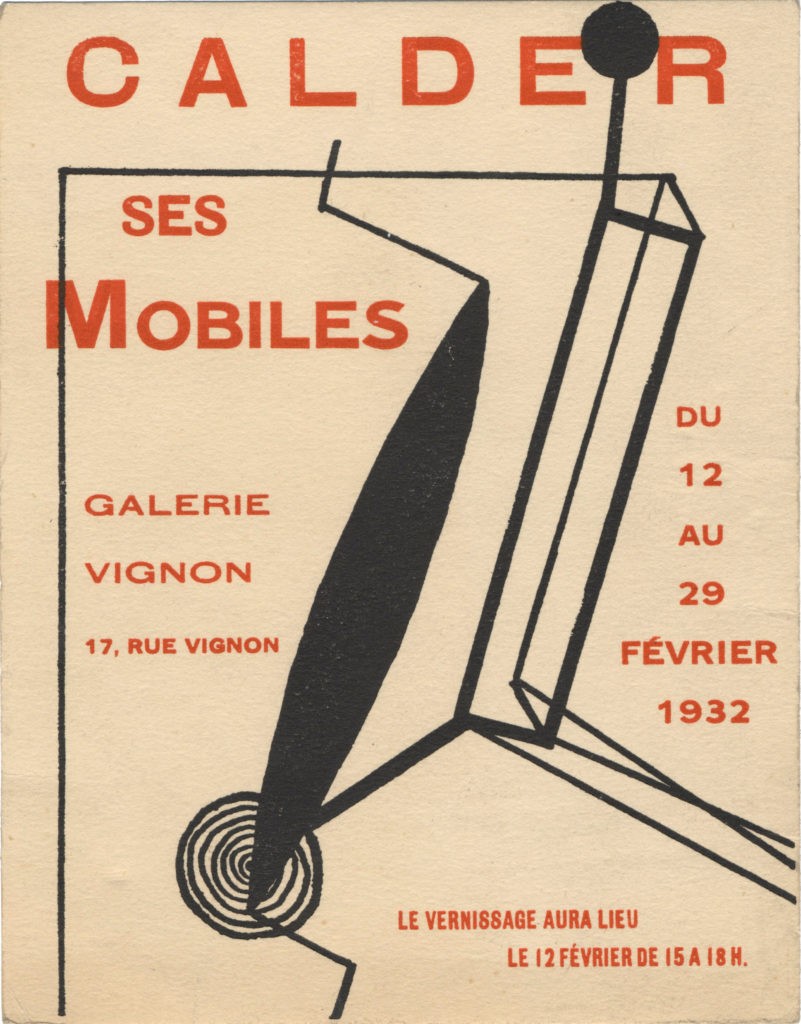

When Calder’s first solo show of mobiles opened at Galerie Vignon in February 1932, some of the most renowned artists at the time were in attendance, among them Fernand Léger, Pablo Picasso, Theo van Doesburg, Jean Cocteau, Piet Mondrian, and Jean Arp. At Duchamp’s suggestion, Calder had made a drawing of the motorized mobile that Duchamp liked on the invitation card and printed “Calder / ses mobiles”—his motions, his motives. The show comprised approximately thirty works, half of which were motorized, the other half “swaying when touched or blown.”[23] It was around the time of the opening of this show that Arp opined to Calder, “Well, what were those things you did last year [for Percier’s]—stabiles?” Calder “seized the term,” as he put it in his autobiography, “[applying it first of all to the things previously shown at Percier’s and later to the large steel objects I am involved in now.”[24] Just as the meaning of the term “mobile” has expanded over the years—from motorized works to all manner of suspended objects—the term “stabile,” too, has since evolved, having first been applied to intimate wire works like Croisière and Circulation but today used to name Calder’s monumental sculptures in bolted steel plate, some of which are well over sixty feet tall. These majestic objects, even though standing still, are always on the move, transforming the public spaces they inhabit, generating fresh perspectives in the midst of the everyday. Notably, in the early 1940s, when Calder devised yet another new form of sculpture—exotic objects made of carved wood and wire, many of which were mounted at surprising moments on the wall—he looked to both Duchamp and James Johnson Sweeney to help name them; they proposed the term “constellation.”

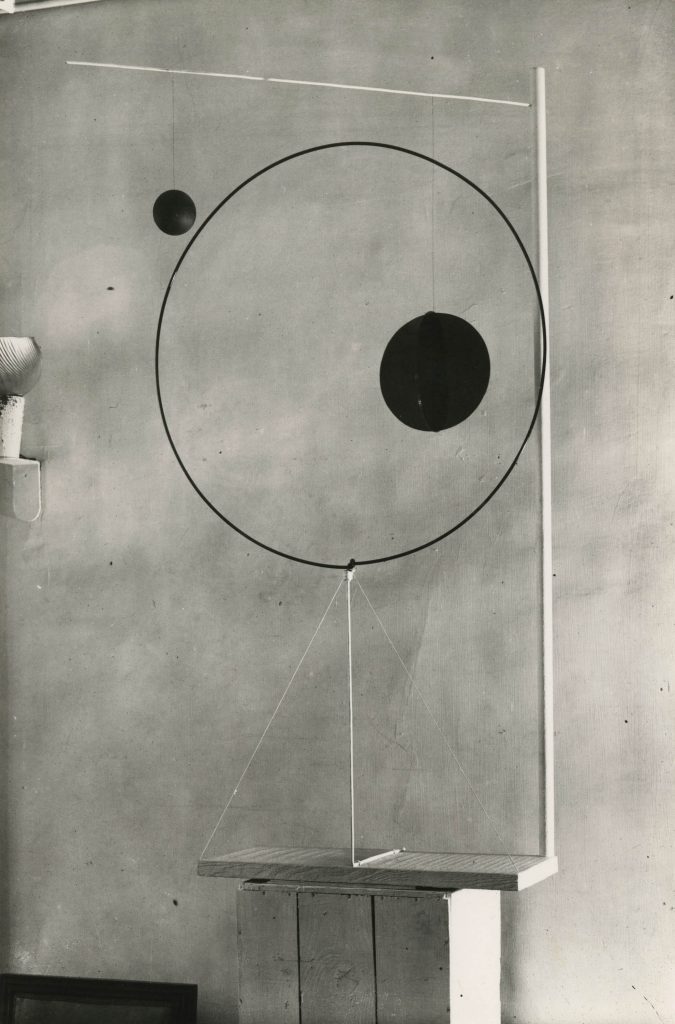

With the presentation at Vignon, the objects that had become mobiles were bent into unfortunate metaphors. “The journalists did not seem to understand anything I was driving at,” recalled Calder. “They just did not, or would not, understand.”[25] In one review for Vu magazine, the headline read “Sculpture Automobile,” and the caption accompanying Vaux’s photograph of an untitled mechanized object from about 1932 noted that Calder’s inspiration came from “gearshifts” and “brakes”; next to the reproduction of Croisière was a misguided description of celestial spheres.[26] Others went on to more vividly capture the action of Calder’s works, among them critic Paul Recht, who wrote about “the grace, uncertainty, and timidity” of the two “simple sticks” in the untitled mechanized object.[27] Recht also described the sculpture’s “[buzzing] like a hive; all of which recalls the approach of the Maenads,” but it is important to remember that many of the motorized works—including the one highlighted by Recht—in fact moved extremely slowly, existing in their own parallel time and space, forcing viewers to pay close attention—or “delay,” to borrow Duchamp’s term. It cannot be overstated that the action of some of these works is so slow as to be imperceptible. In a sense, they, too, are about indecisive reunions—at once mechanical and meditative, forward-looking and immediate—the opposite of a flustered, thin experience. “Nothing at all of this is fixed,” wrote Calder at the time, underscoring the notion of disparity within his works. “Each element able to move, to stir, to oscillate, to come and go with the other elements in its universe.”[28]

So much has been written on Calder and the universe, but the universe was not Calder’s subject: “Whatever sphere, or other form, I use in these constructions does not necessarily mean a body of that size, shape or color, but may mean a more minute system of bodies, an atmospheric condition, or even a void. I.E. the idea that one can compose any things of which he can conceive.”[29] A work like Croisière, with spheres both massless and solid, is not a diagram of planets but an object “based on a concept of nuclei in space of various intensities, distributions, etc.,” as Calder expressed in a letter to collector Albert E. Gallatin.[30] In a 1935 etching that he made for a portfolio organized by critic and poet Anatole Jakovski, Calder conveyed this notion through the directives grandeur–Immense (“size–Big”), written on the bottom left recto. These words, on the one hand, indicate the scale he intended for that particular ballet object, to be enlarged for a theoretical future stage performance, and on the other, they point to the expansiveness of Calder’s outlook, expressed through works both small and large, and in resonance with notions of the sublime: a questioning of our place within nature’s totality. Considering Calder’s sweeping vision, which dissolves the divide not only between object and spectator, but also art and nature, it comes as no surprise that spheres, circles, and discs prevail as visual identities in his work. The circle, to quote philosopher Ralph Waldo Emerson, is the “highest emblem in the cipher of the world,” extending from the circle of the eye to the horizon that the eye forms, indicating a circumference of the unseen circulating infinitely outward. “Our life is an apprenticeship to the truth that around every circle another can be drawn; that there is no end in nature, but every end is a beginning; that there is always another dawn risen on mid-noon, and under every deep a lower deep opens.”[31]

In 1951, twenty years after originating the mobile, Calder composed a brief statement for a symposium at The Museum of Modern Art, New York, in which he concluded: “That others grasp what I have in mind seems unessential, at least as long as they have something else in theirs.”[32] For a man of few words, Calder produced objects with boundless narratives that challenge our limits of longing for definitions or answers; in 2019, as in 1931, there is no “final person” who decides. Just as the most personal stories have the most universal reach, his mobiles instigate individual encounters that arouse a diverse range of impressions, emotions, and interpretations—not just among us, but within us. Two years after the artist’s death, James Johnson Sweeney remarked, “Every exhibition of [Calder’s] work was open-ended, ‘prospective,’ as … one always had the feeling that one had another step to go, one intimately part of the latest—not something alien to the latest, but something growing out of it.”[33] The organic nature of Calder’s aesthetic remains today something that many of us who admire his mobiles endeavor to describe. Perhaps it is because, in doing so, we are encouraged to name our own experience.

Pace Gallery, New York. Calder: Small Sphere and Heavy Sphere. 14 September–26 October 2019.

Solo ExhibitionHauser & Wirth, Somerset, England. Calder: From the Stony River to the Sky. Exhibition catalogue. 2018.

Susan Braeuer Dam, For the Open Air

Jessica Holmes, More than Beautiful: Politics and Ritual in Calder’s Domestic Items

Solo Exhibition Catalogue“Calder in France.” Cahiers d’Art, no. 1 (2015). Edited by Alexander S. C. Rower.

Susan Braeuer Dam, Calder in France

Robert Melvin Rubin, An Architecture of Making: Saché and Roxbury

Agnès Varda in conversation with Joan Simon

Magazine, MonographMusée Picasso, Paris. Calder-Picasso. Exhibition catalogue. 2019.

Bernard Ruiz-Picasso and Alexander S. C. Rower, Confronting the Void

Chus Martinez, No Feeling Is Final

Group Exhibition Catalogue“Calder in France.” Cahiers d’Art, no. 1 (2015). Edited by Alexander S. C. Rower.

Susan Braeuer Dam, Calder in France

Robert Melvin Rubin, An Architecture of Making: Saché and Roxbury

Agnès Varda in conversation with Joan Simon

Magazine, Monograph