At first [my] objects were static (“stabiles”), seeking to give a sense of cosmic relationship. Then I felt that these relations were possibly not the most important and I introduced flexibility, so that the relationships would be more general. From that I went to the use of motion for its contrapuntal value, as in good choreography.[1]

Alexander Calder

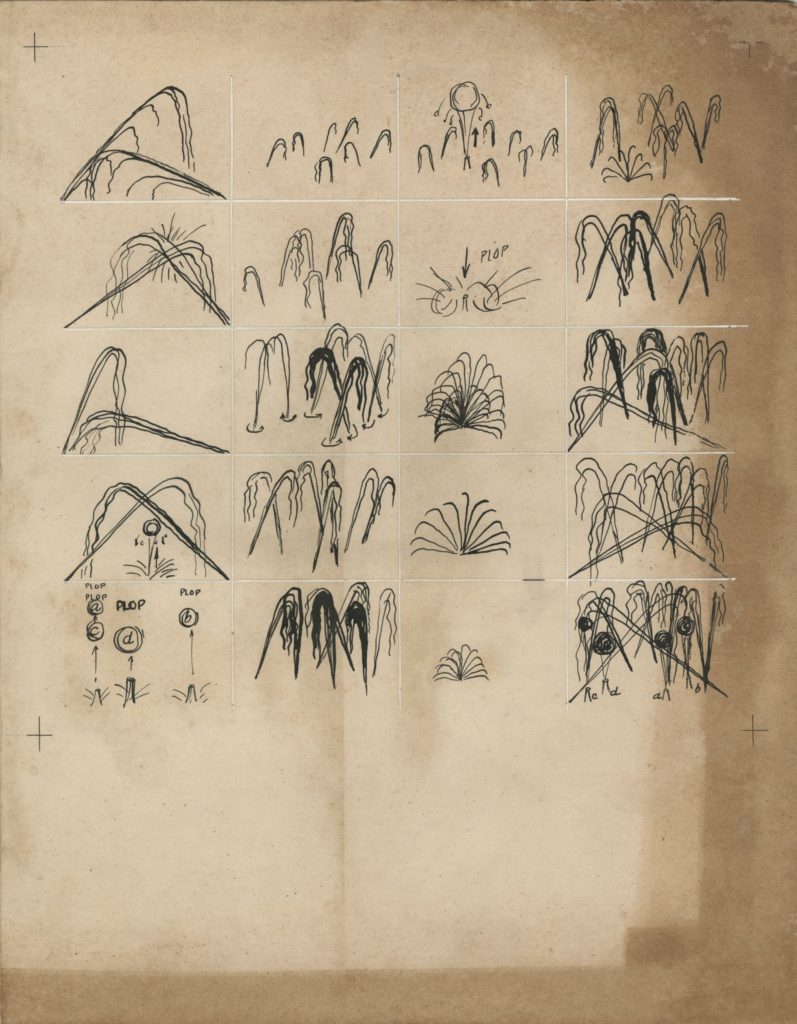

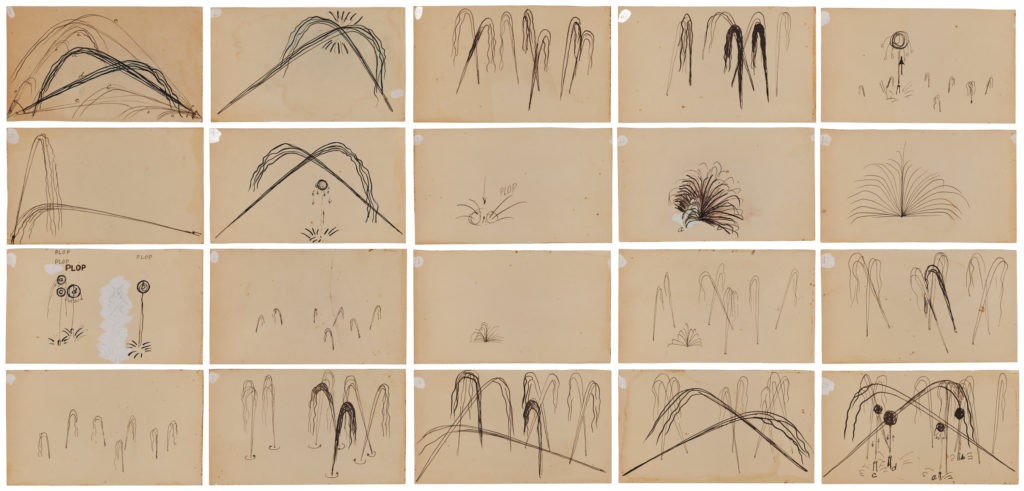

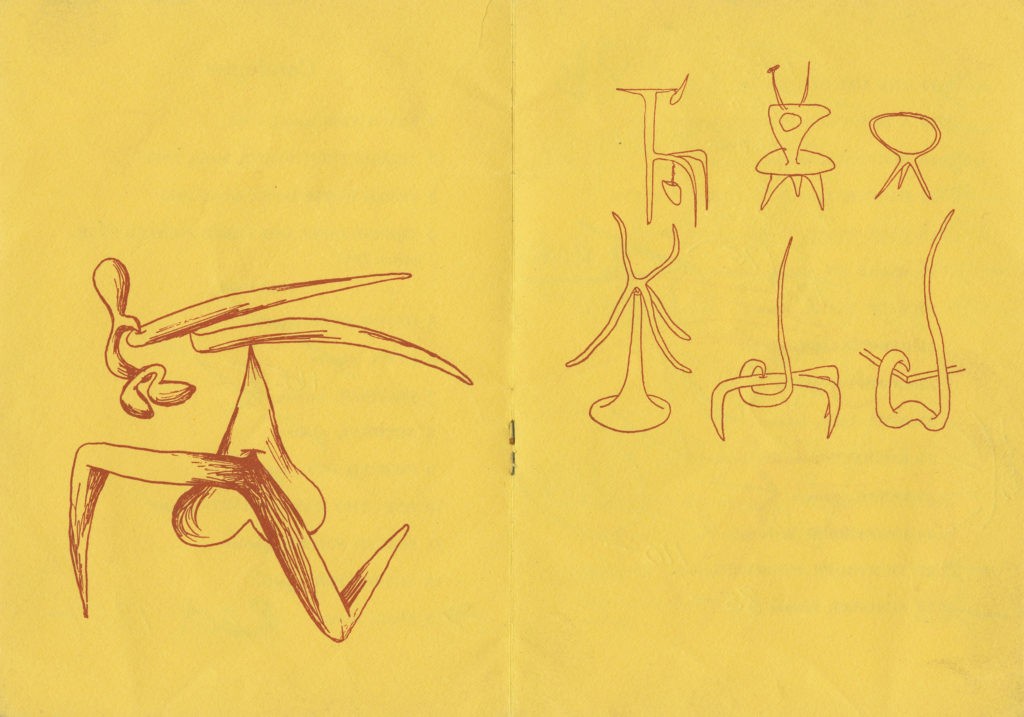

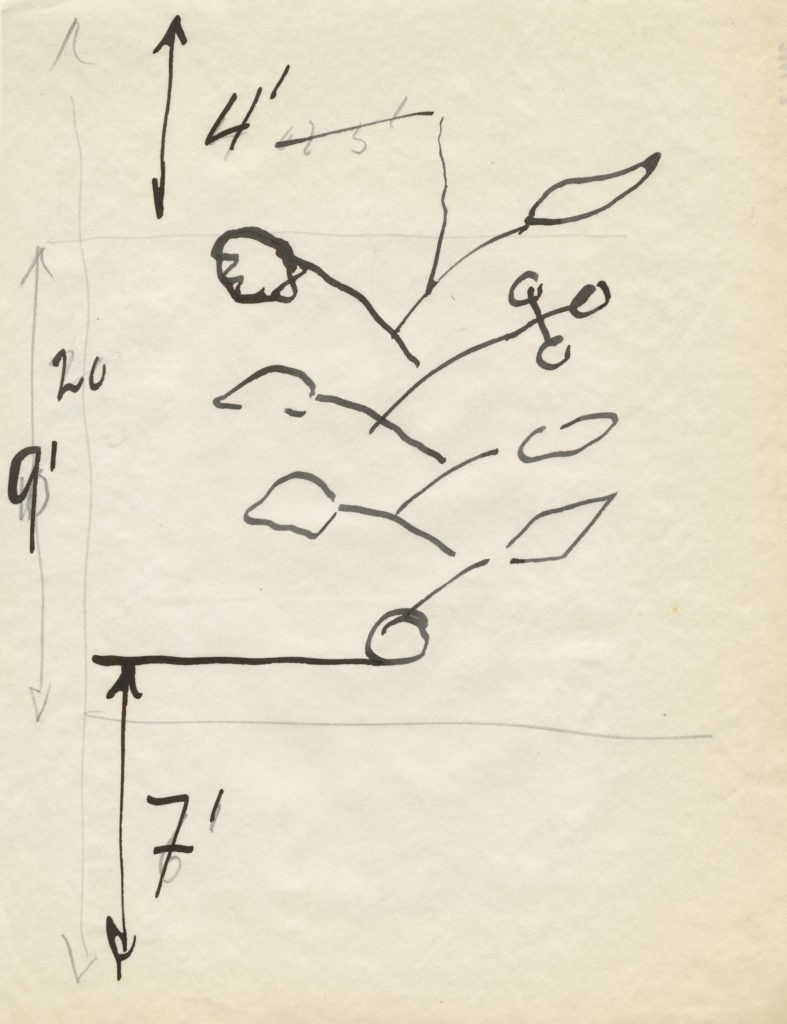

In the 1930s, Calder worked on a number of proposals for kinetic décor. They ranged from relatively small-scale “ballet-objects” to projects that he hoped would be realized within the proscenium arch of the theatrical stage. His diagrammatic notations for these performances reveal a complex choreography of nonobjective forms that was meant to erase boundaries between traditional genres of music, dance, theatre, painting and sculpture. These performative concepts began in 1933 with a plan for the Ballet Russe de Monte Carlo—a collaboration with Léonide Massine that never came to be.[2] Through the commission of curated interpretations of these drawings for the presentation at Centro Botin, viewers

are given animated demonstrations of what my grandfather had in his mind, conceived not only in space but also in time.

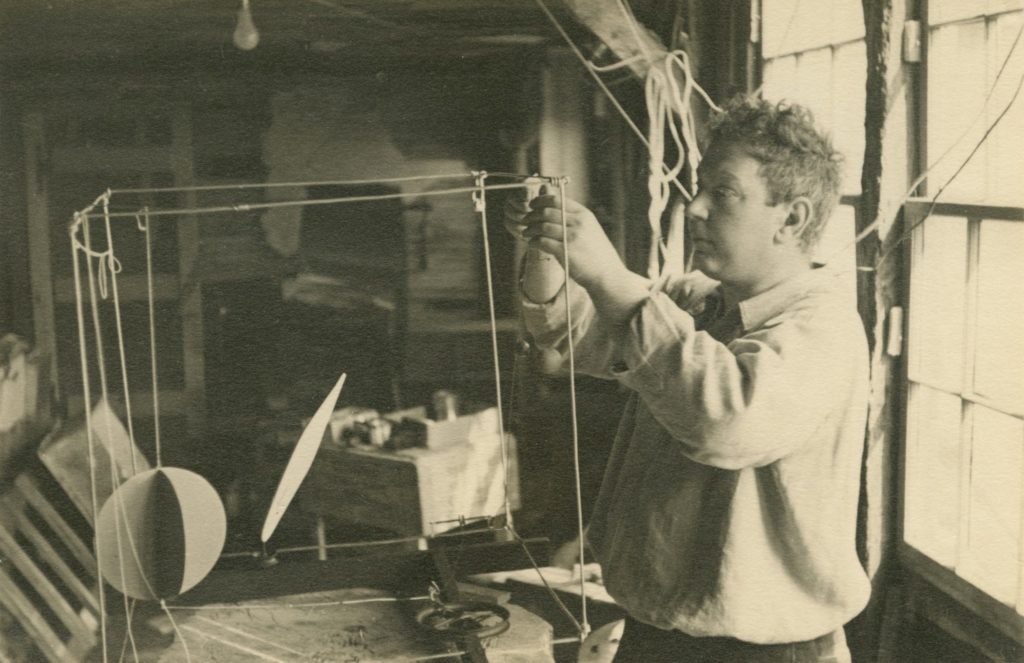

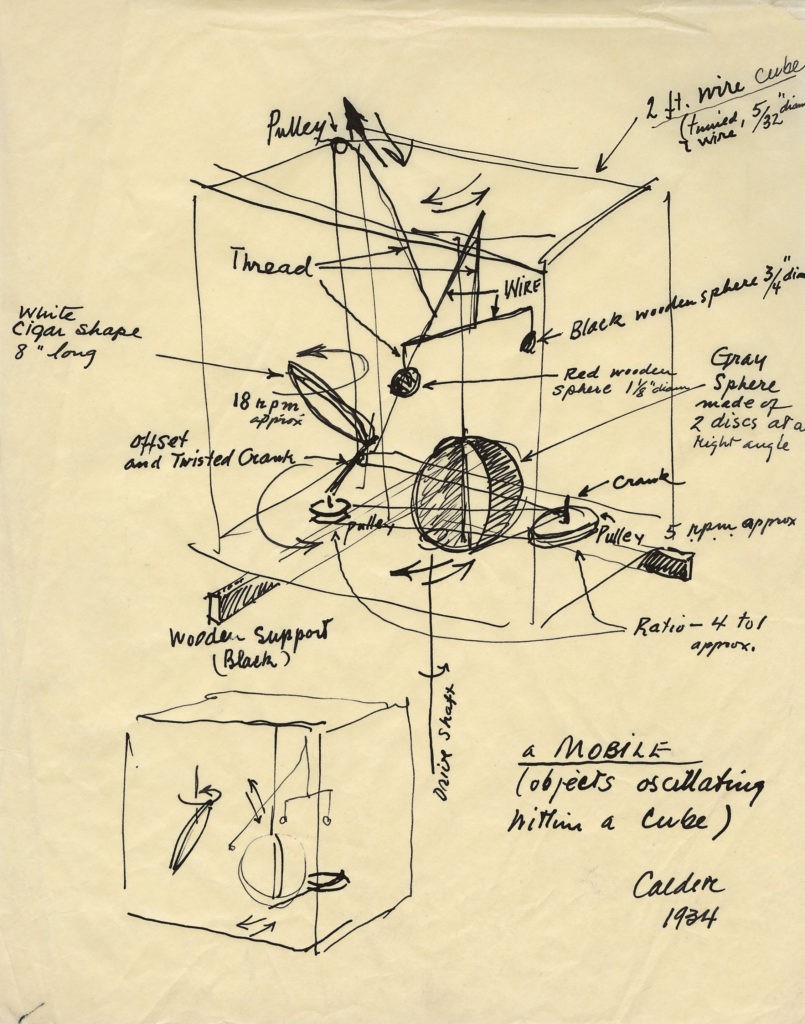

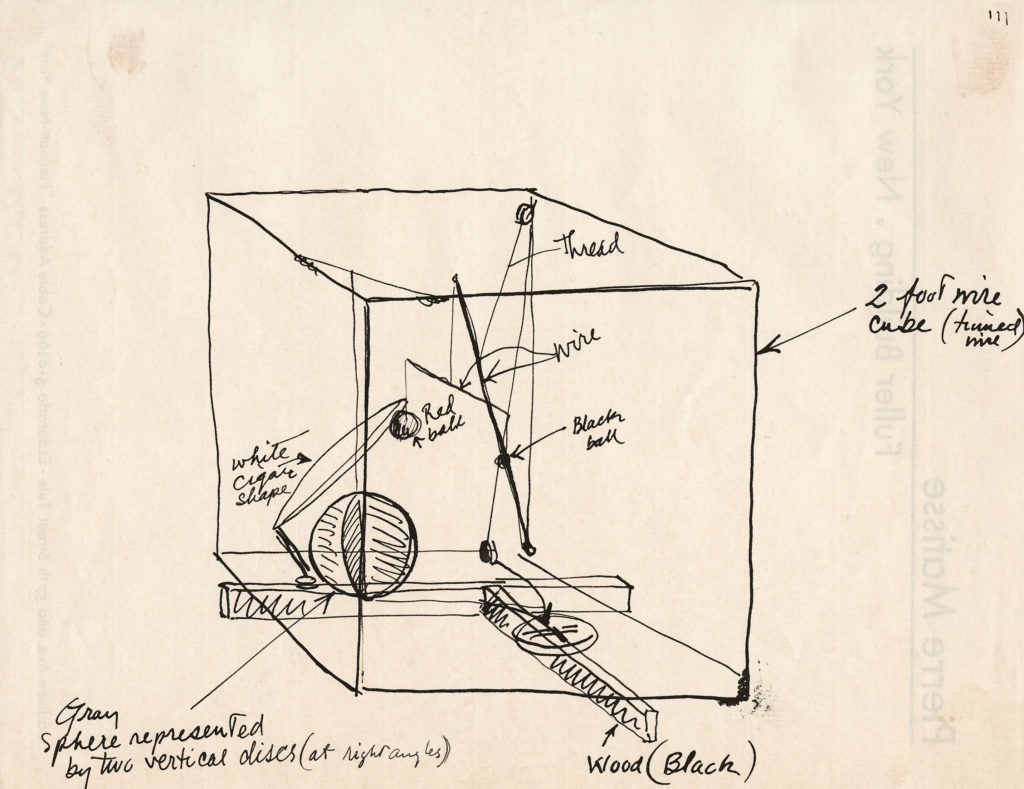

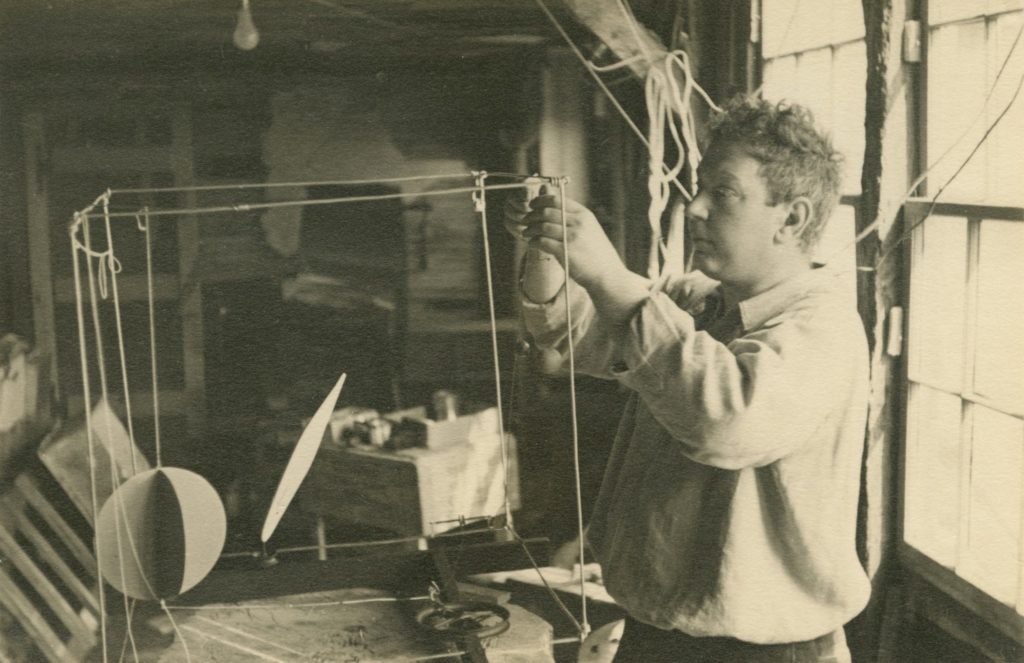

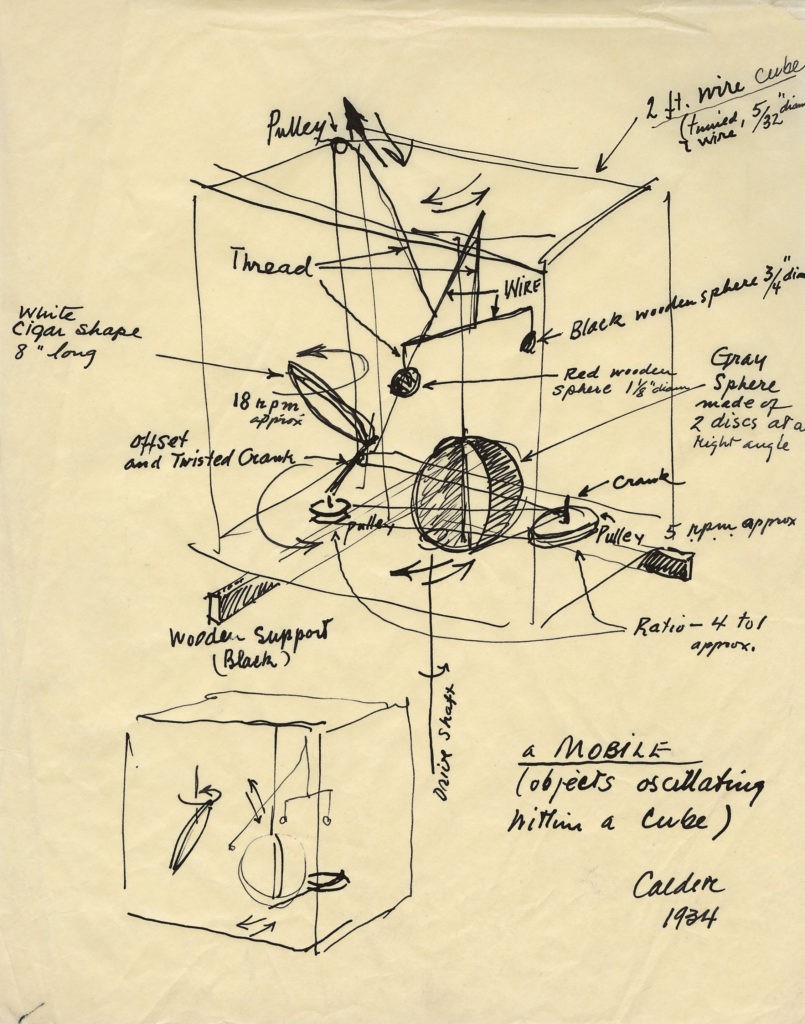

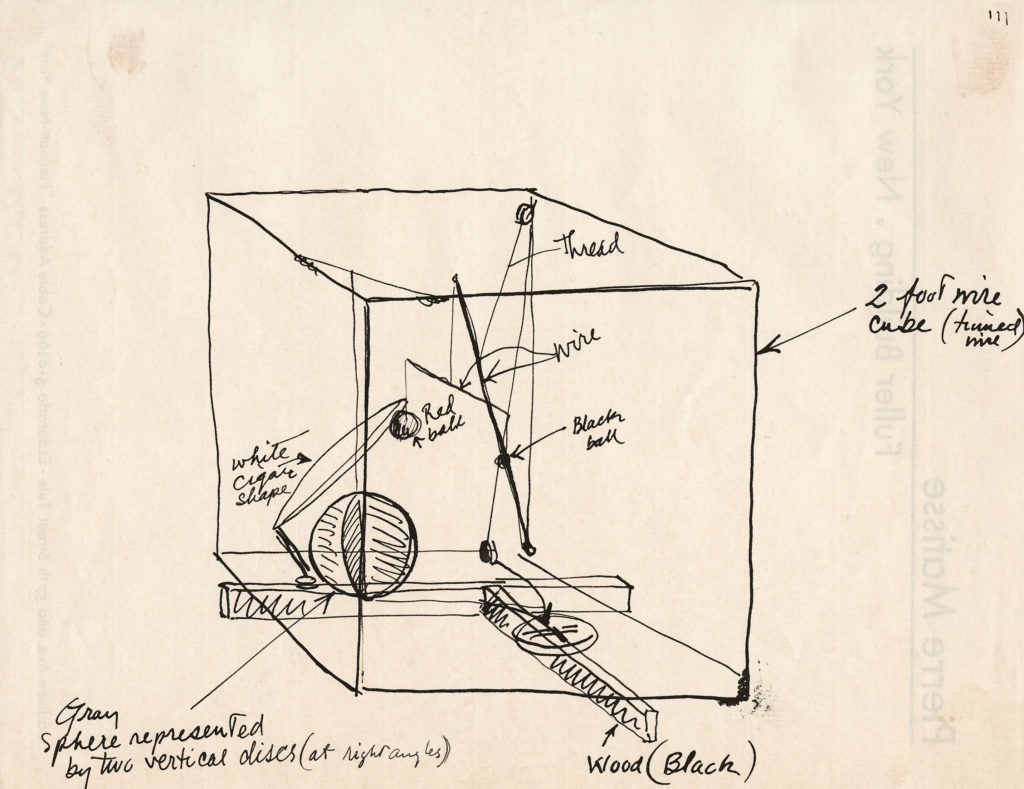

Ballet in Four Parts is a series of drawings from about 1934 that Calder made in Roxbury, Connecticut, as part of a collaborative project with composer Harrison Kerr, whom he had met through his close friend the composer Edgard Varèse. My grandfather also prepared for his collaboration with Kerr a maquette entitled Objects Oscillating Within a Cube; this consisted of a cubic volume supporting nonobjective forms that were activated by ropes and pulleys. Calder later expanded on this idea with a group of motorized maquettes that broke with the framing proscenium. He hoped to see these maquettes realized in the open air on a monumental scale for the 1939 New York World’s Fair, but at the time was unable to interest anybody in the project.

Grandeur-Immense is an etching that was included in 23 Gravures de Arp, Calder, Chirico, Erni, Ernst, Fernández, Giacometti, Ghika, González, Hélion, Kandinsky, Léger, Lipchitz, Magnelli, Miró, Nicholson, Ozenfant, Picasso, Seligmann, Taeuber-Arp, Torres-García, Vulliamy, Zadkine, a portfolio organized by the critic Anatole Jakovski[3] in 1935. While his contemporaries produced handsome works in their signature styles, Calder instead contributed a diagrammatic proposal for a future theoretical performance—a radical suggestion in itself. In the etching, Calder includes directives in French, indicating the colour of both the elements and background as well as the relative speed of the actions. In the bottom left recto, he writes “grandeur–Immense,” which not only translates to “size–Huge” but also points to an encompassing sensibility in Calder’s art: his engagement with the unseen forces that challenge our inherently limited perception of expanding dimensions. My grandfather wanted us to experience the immensity and grandeur of everything—even the smaller things—in our world.

For a portfolio designed to benefit the Surrealist magazine VVV, which was published in New York in the early 1940s, Calder created an etching, Score for Ballet 0–100, which relates to Grandeur-Immense. The other contributors to the portfolio were André Breton, Leonora Carrington, Marc Chagall, Marcel Duchamp, Max Ernst, André Masson, Matta, Robert Motherwell, Kurt Seligmann, and Yves Tanguy. In his Score for Ballet 0–100, Calder diagrams the movements of elements in time-space intervals as fractions of 0–100, suggesting that the performance speed was fungible according to the musical duration. My grandfather continued to explore these notations in various scenarios throughout the 1940s, as seen in some untitled drawings from 1942 and 1948.

Mondrian lived at 26 rue de Départ. (That building has been demolished since, to make more room for the Gare Montparnasse.) It was a very exciting room. Light came in from the left and from the right, and on the solid wall between the windows there were experimental stunts with coloured rectangles of cardboard tacked on. Even the victrola, which had been some muddy colour, was painted red. I suggested to Mondrian that perhaps it would be fun to make these rectangles oscillate. And he, with a very serious countenance, said: “No, it is not necessary, my painting is already very fast …” This one visit gave me a shock that started things. Though I had heard the word “modern” before, I did not consciously know or feel the term “abstract.” So now, at thirty-two, I wanted to paint and work in the abstract. And for two weeks or so, I painted very modest abstractions. At the end of this, I reverted to plastic work which was still abstract.[4]

Alexander Calder

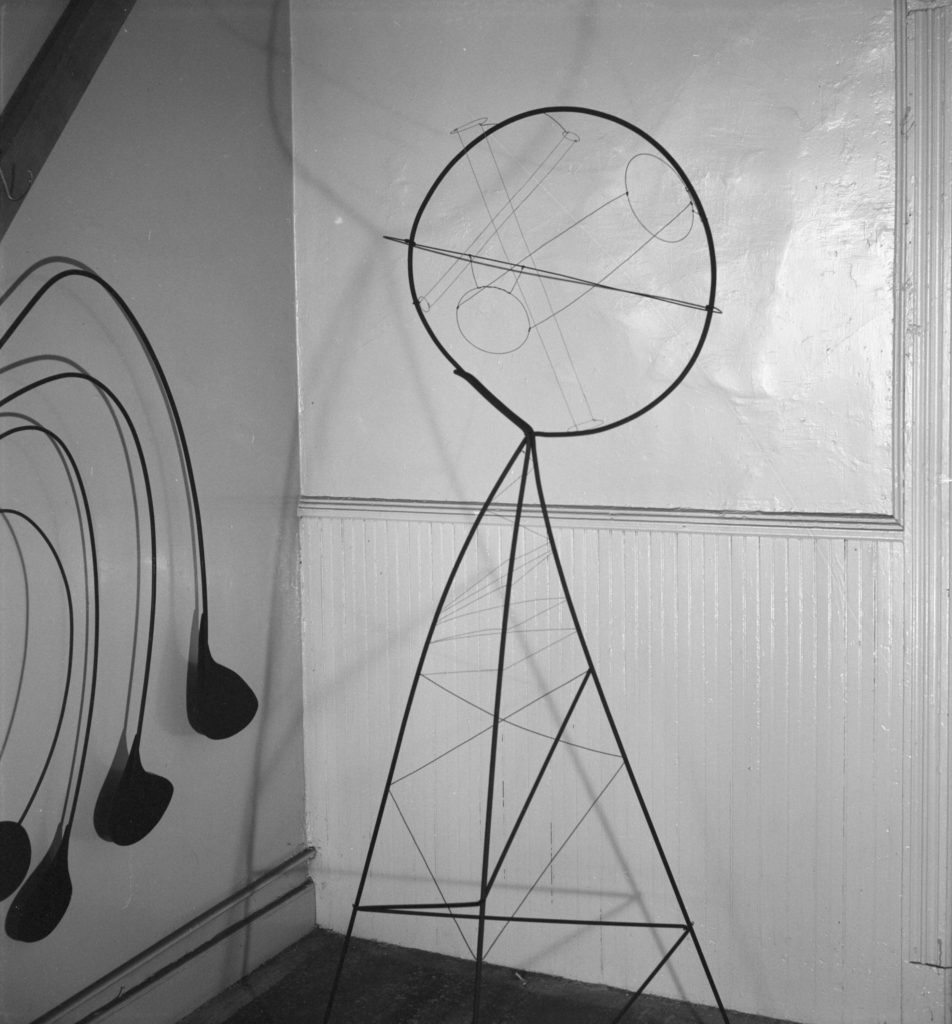

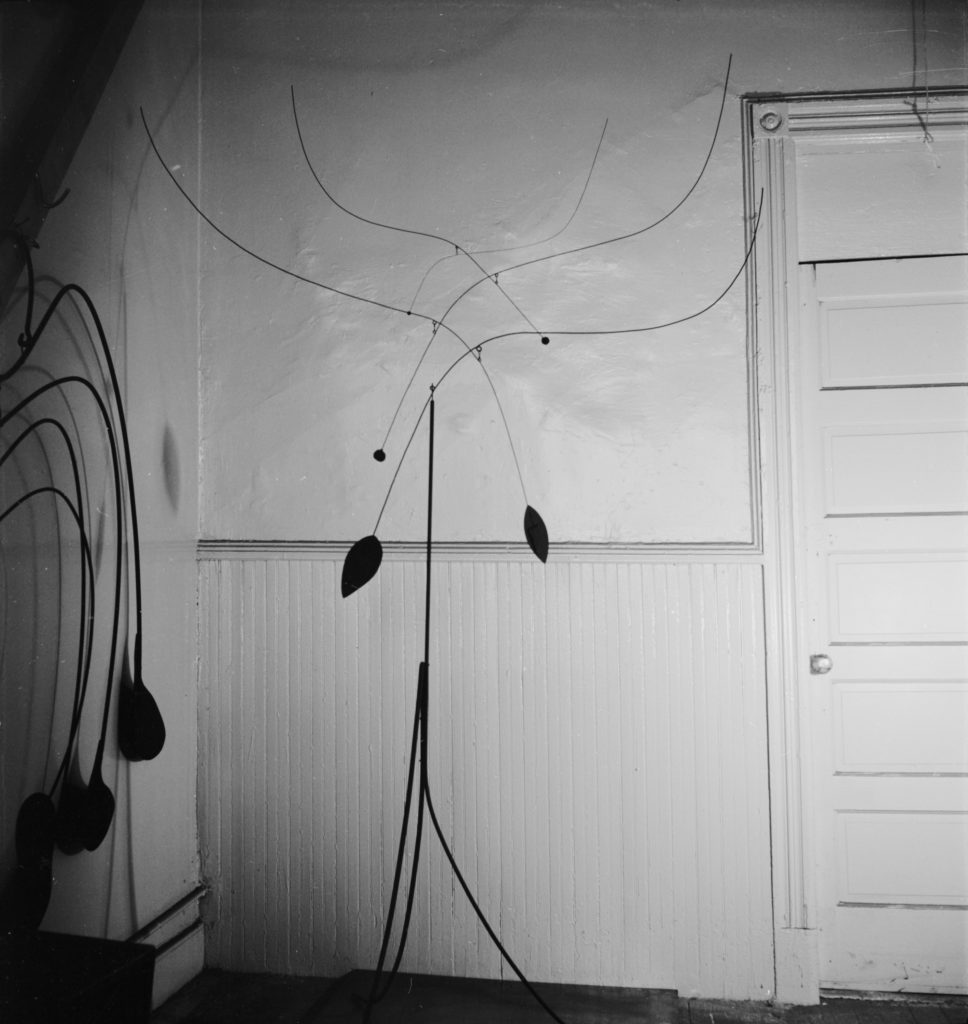

It was not Piet Mondrian’s geometric paintings that astonished Calder during his visit to the Dutchman’s studio in October 1930, but rather the way Mondrian activated the space, creating what my grandfather saw as an all-encompassing environmental installation. The back wall of coloured cardboard rectangles, which Mondrian moved around as he experimented with compositional possibilities, inspired my grandfather’s embrace of total abstraction. In 1931, Calder began to explore the frontal formality of painting rendered in three dimensions yet with actual motion, conceiving them as recomposable compositions. In Snake and the Cross (1936), multi-coloured elements oscillate in front of a defined area bounded by a wooden frame. The mobile elements are moved by the caprices of the air or can be recomposed intentionally by the viewer. In Square (c. 1934), a single rounded form, propelled by a hidden mechanism, oscillates from white to black in front of an acid yellow wavy panel. Viewed head-on, these exotic sculptures become paintings whose compositions mutate form and colour, blurring the lines between fixedness and transformation and activating a choreography of nonobjective imagery.

In 1939, Wallace K. Harrison’s architectural firm was planning a new African habitat for the Bronx Zoo in New York City. The project was spearheaded by the young architect Oscar Nitzchke, and Calder was asked to create a series of sculptures, a sort of imaginary flora that would become the setting for the actual fauna. “The main idea was to put the tough guys (lions, etc.) behind a moat. We even had the visitors walking through an armoured tube.

My objects, I felt, could replace trees, being iron they would be immune to the animals’ claws.”[5] Calder’s objects are not representations of the natural world but abstractions of the forces that shape the natural world. Marcel Duchamp said, “The art of Calder is the sublimation of a tree in the wind.”[6] Calder wanted his objects to operate within the intricate fabric of the surrounding habitat.

Although the Bronx Zoo project was never realized, Calder created five models: Sphere Pierced by Cylinders, Four Leaves and Three Petals, Leaves and Tripod, The Hairpins, and Hollow Egg. In 1970, Calder rediscovered some of these objects at his studio in Roxbury, Connecticut, in a loft overhanging the garage. When they were exhibited at his New York gallery that fall, the critic John Canaday declared, “They are among the least discardable Calders imaginable.”[7] Ironically, it was sometimes “discardable” materials—leftover bits of wire and sheet metal, and broken pieces of glass—that my grandfather transformed into his finest compositions.

Wally Harrison was going to put up a water ballet of mine in front of the New York Edison building, but the guy who controlled the manufacturer of the pumps never did come through … finally nothing happening. So much later, I did that for [Eero] Saarinen who did General Motors.[8]

Alexander Calder

For the 1939 New York World’s Fair, Calder received a commission from Wallace K. Harrison and André Fouilhoux, architects of the Consolidated Edison pavilion, to produce an extraordinary fountain for the pool in front of their building. My grandfather’s Water Ballet was to consist of a program lasting five minutes—with fifteen minutes or more between performances—that would include a choreography of “jets of water from 14 nozzles … designed to spurt, oscillate or rotate in fixed manners and at times as carefully predetermined as the movements of living dancers.” These movements were to be interspersed with water bombs, each a “large detached mass of water which gives off a considerable report when it falls back onto the surface of the lagoon.”[9] Although the water jets were installed at the pavilion, the ballet was never executed.

Calder’s friend, the critic and curator James Johnson Sweeney, later commented that, “Unfortunately, he did not receive the same sympathetic cooperation from the New York engineers in charge that he had in Paris,” writing in reference to my grandfather’s fearsome Mercury Fountain (1937), made for the Spanish Pavilion at the Paris World’s Fair. “Although the necessary equipment was installed, a failure to follow the stipulated timing destroyed the possibilities of rhythmic variation and defeated the ballet effect.”[10] The drawings on view at Centro Botín are the clearest indications we have today of my grandfather’s intentions.

In 1956, Calder completed a different Water Ballet for Eero Saarinen’s General Motors Technical Center in Warren, Michigan. While the composition of the project is entirely separate from his 1939 Water Ballet, it reveals my grandfather’s fascination with gestures at once grand and ephemeral.

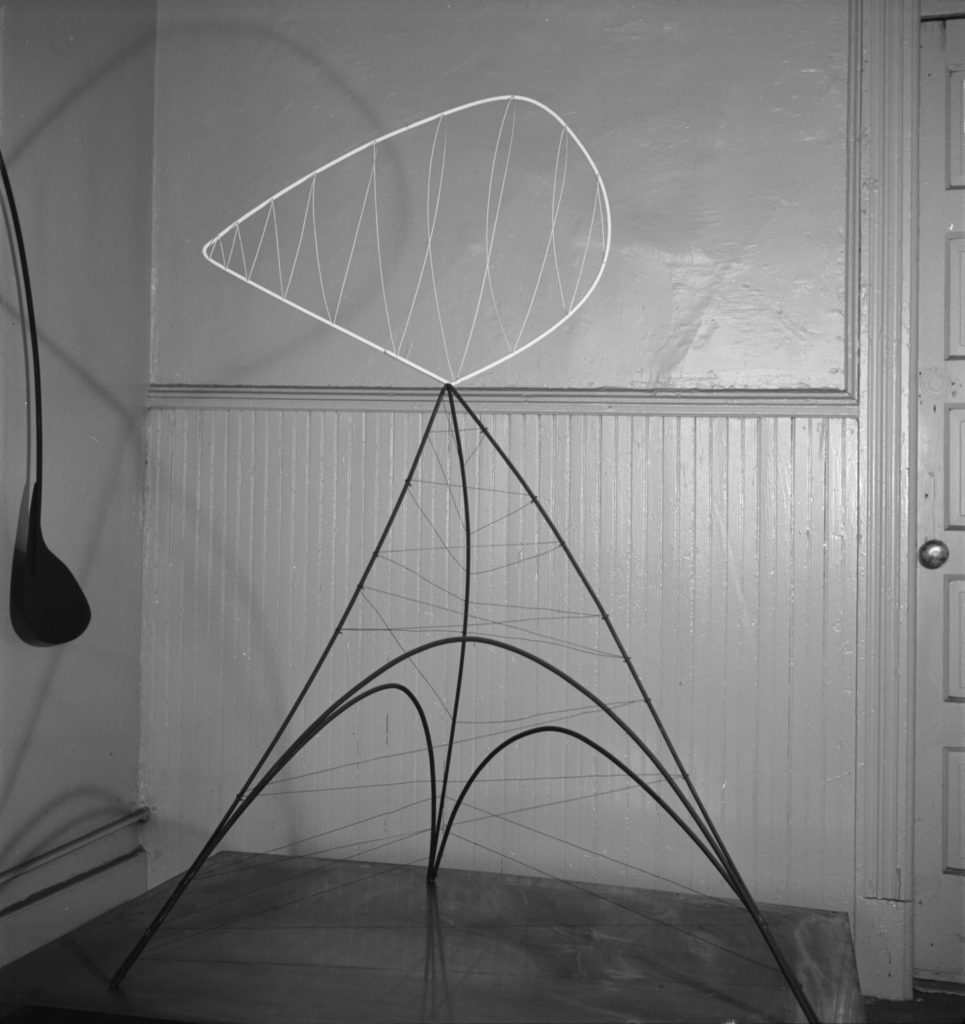

Concurrent with his Water Ballet commission for the Consolidated Edison building at the 1939 New York World’s Fair, Calder worked on three maquettes that he hoped would be adapted for a large-scale kinetic sculptural environment. My grandfather postulated that the visitors at the World’s Fair could have a transformative experience in and around his dynamic installation. In each of the three maquettes, Calder organized four multi-coloured abstract forms on a shared stage, with each object’s movement activated in idiosyncratic ways. While none of them were realized in 1939, one of the maquettes was used in 1961 as the model for The Four Elements, commissioned and enlarged by Pontus Hulten, director of the Moderna Museet in Stockholm, as a permanent outdoor installation some nine metres high for their exhibition Rörelse I konsten (Movement in Art). This was one of the many examples throughout my grandfather’s career when a maquette or small-scale sculpture from decades earlier was reimagined for a new project.

Calder made small-scale works for many reasons, sometimes as proposals to be presented to architects and their clients. These six standing mobiles from 1939, made of wood, wire, and sheet metal, were produced for the architect Percival Goodman, as part of Goodman’s submission to a competition for a new Smithsonian Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C. Goodman did not win the competition. The winning design—by the father and son team Eliel and Eero Saarinen, who were also friends with my grandfather—was never realized. The project was likely postponed due to World War II. Washington’s National Gallery of Art, although initially conceived in the 1930s as a museum dedicated to the old masters, has in more recent times become a major repository of twentieth-century art, and now boasts the largest permanent gallery devoted to Calder in the world. We can only imagine these maquettes in a full scale, with mobiles perched atop imposing granite plinths, together representing potential and actualized kinetic energies.

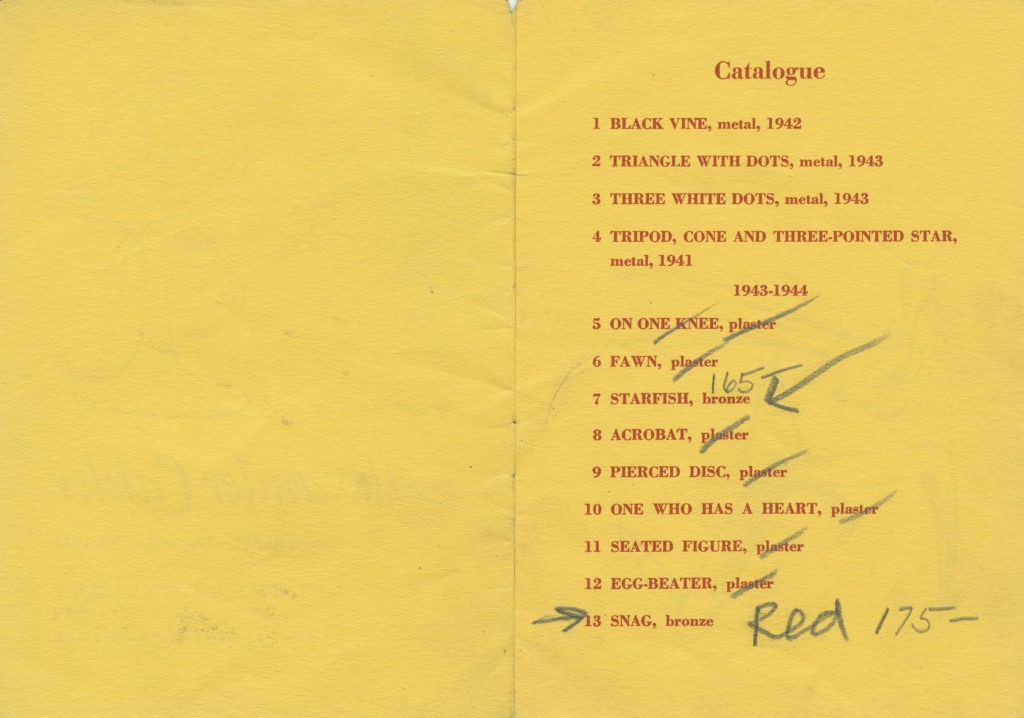

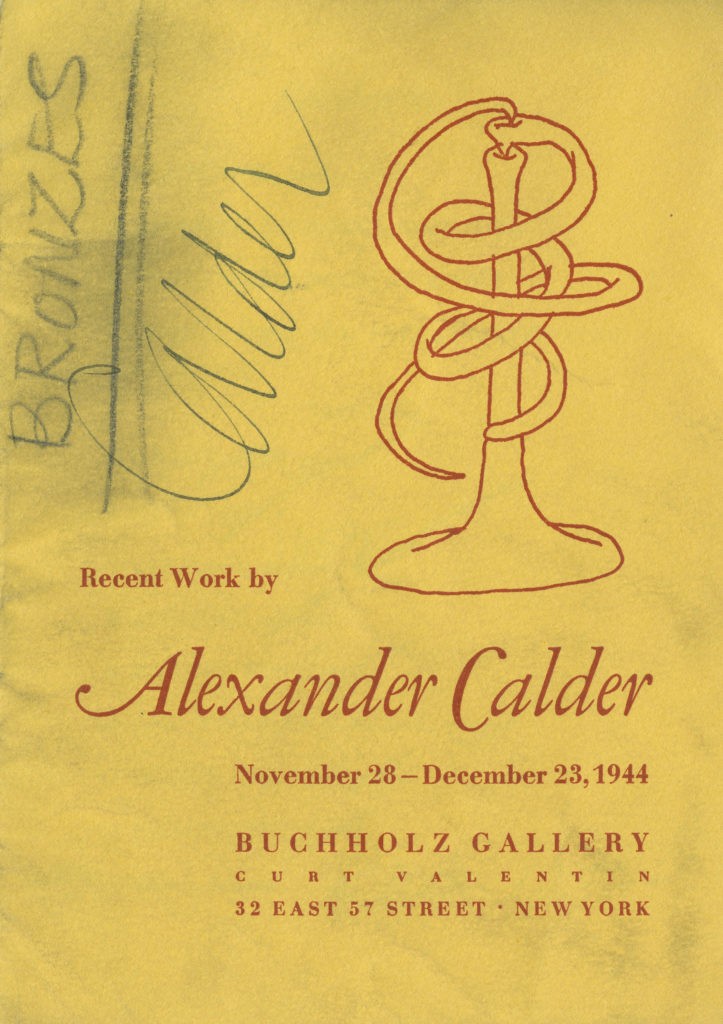

In the spring of 1944, the architect Wallace K. Harrison suggested that Calder sculpt large outdoor works in concrete for an International Style architectural project. As Calder recalled in his autobiography, “Wally Harrison had suggested I make some large outdoor objects which could be done in cement. He apparently forgot about his suggestion immediately, but I did not and I started to work in plaster. I finally made things which were mobile objects and had them cast in bronze—acrobats, animals, snakes, dancers, a starfish, and tightrope performers.”[11] In November of that year, Buchholz Gallery/Curt Valentin in New York devoted its first Calder exhibition to these modeled forms in plaster and bronze. The artist’s illustrations of the sculptures—along with handwritten prices and notes—can be seen in the annotated catalogue from the Calder Foundation’s archives.

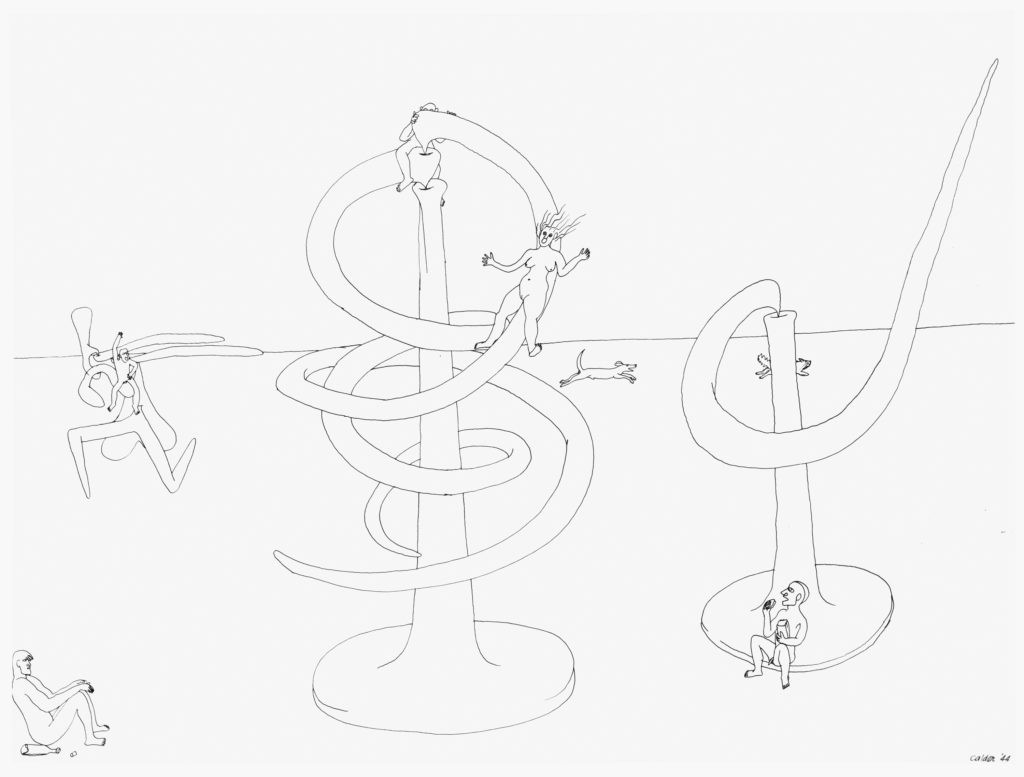

It is critical to remember that these handsome bronzes of 1944 were not intended for a domestic setting, nor were they conceived on a human scale. Instead, they were envisioned as giant monuments to exist some 30 or 40 feet tall. Try to imagine how imposing On One Knee would have been in modern concrete with its six separate and balanced sections as huge lumbering forms, gesticulating high above. Considering its size and the fact that it was contemporaneously cast in aluminum, On One Knee was likely the work that Calder chose for Harrison’s approval. A sense of the scale Calder envisioned for the works can be divined from drawings in which humans and animals frolic on his bronzes.

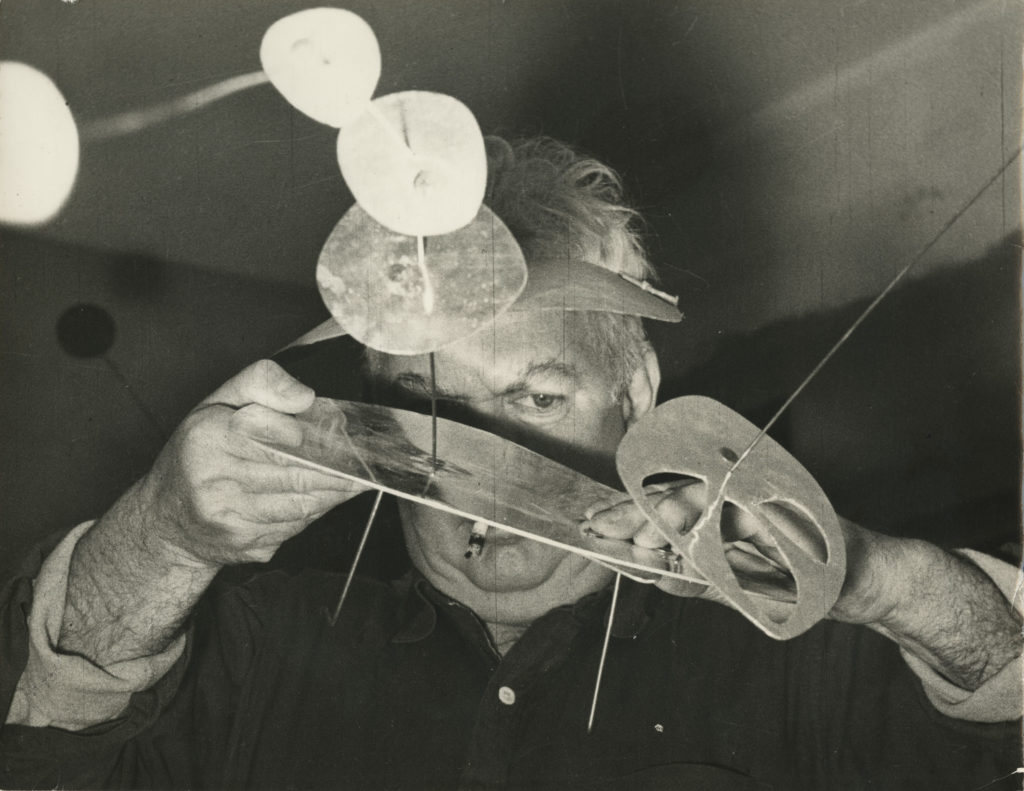

In 1943, Calder ruminated, “A knowledge of, and sympathy with, the qualities of the materials used are essential to proper treatment … Bronze, cast, serves well for slender, attenuated shapes. It is strong even when very slender.”[12] A year later, Calder stretched the medium to its limits. In Egg-Beater, Calder devised a way to make bronze permeable with undercut forms of string, wire, and coatings of plaster that technicians then had to somehow figure out how to cast. In kinetic works such as The Helices, the tremendous extension of the lines without additional structure allows two helixes to balance on point such that they can rotate in syncopation or opposition. A recently discovered photograph from around 1948 attests to the sheer range of experimentation in plaster that took place during this time. Atop the piano in his jam-packed Roxbury studio rests a forest of plasters, a tangled mass of elongated extremities.[13]

While Calder’s experimentation in bronze began [in 1930] with convenience—the Fonderie Valsuani, located at 74 rue des Plantes, was only 120 meters from his studio at 7 Villa Brune in Paris—it ended with an irrepressible exploration of stretching, pulling, and layering the medium. Recalling his 1944 bronzes, Calder remarked, “This was rather an expensive venture and did not sell very well, so I abandoned it for my previous technique. It was also disagreeable to have to check the manipulations of some other person working on the objects at the foundry. However, I play with the idea, from time to time, of going back to this medium.”[14]

My grandfather received many international commissions in the 1950s. In January 1954, he travelled to Beirut to make a large-scale hanging mobile for Middle East Airlines’ central office. The airline provided him with a small room in their building, at the time under construction, to use as a makeshift studio. Calder made the commissioned mobile as well as Escutcheon. Escutcheon was given to Henri and Miette Seyrig, the friends with whom my grandparents, my mother, and my aunt were staying in Beirut. Calder also made a polychrome mobile for the home of the commissioner, Assem Salaam.

A year after the Middle East Airlines commission, in January 1955, my grandparents travelled to India at the invitation of Gira Sarabhai, who had offered an expansive tour of the country in exchange for a few works of art. Before embarking on their expedition, they spent a few weeks at the Sarabhais’ home in Ahmedabad, where Calder made many sculptures, including Guava, Franji Pani, and Red Stalk. With a span of over three and a half metres, Guava was the largest of the works and was installed over a swimming pool. In all his working trips, from Lebanon to India to Venezuela, which followed in August 1955, my grandfather had little more than three weeks to fulfil his onsite commissions, generally working in less than ideal studios.

In 1956, Chase Manhattan Bank approached Calder with a commission for One Chase Manhattan Plaza, an office complex conceived by Gordon Bunshaft, the lead architect in the firm of Skidmore, Owings & Merrill. With funding from the Chase Art Committee, Calder created a series of Three Legged Beastie maquettes in 1959; a nearly one-and-a-half metre tall brazed bronze intermediate-sized model was submitted for consideration. Eventually, in March 1961, the committee rejected Calder’s proposal, but they invited him to make a second submission. An artist had yet to be secured for the project by the mid-1960s, when Calder submitted two new maquettes, The Long Plate (c. 1964) and Archway in Two Sections (1965). These were also rejected by the committee, in January 1966. The commission was ultimately awarded to Jean Dubuffet in 1968 for Group of Four Trees (1969–72).

In 1967, following his final two proposals to the Chase Art Committee, Calder created Four Planes Escarpé and Six Planes Escarpé. Here the steel plates slice dramatically through space, creating voids that push up from the ground. There are only three planes in the maquette for Four Planes Escarpé. But a pencil line by Calder, on the model’s tallest element, indicates the plan for the fourth plane in the monumental version. Calder’s maquettes, direct sketches of ideas, provide extraordinary insight into both his initial inspirations and his evolving intuitions.

[Commissions] give me a chance to undertake something of considerable size. I don’t mind planning a work for a given place. I find that everything I do, if it is made for a particular spot, is more successful. A little thing, like this one on the table, is made for a spot on a table.[15]

Alexander Calder

In 1959, the art dealer Rudolph Hoffman commissioned Calder to make a mobile for a stairwell measuring over eight metres. Calder conceived a bold and muscular composition standing at 2.7 metres defined by dramatically diagonal movements. Hoffman, who wasn’t entirely happy with the work, asked my grandfather to revise it. Calder added a high horizontal group of elements, so that the mobile engaged a viewer when seen from directly below. But ultimately Hoffman felt it was just too big. Calder, however, was still very interested in the idea and proceeded to make a new, similar composition, but smaller: For the Staircase.

My grandfather kept the big mobile for himself. He presented it in his large retrospective at the Tate Gallery in London and called it All Black with One Red. By 1963, he had reconsidered the mobile again, enlarging it further and bringing it to its completed state by adding a third constellation of six vertical elements. His new title, Rouge triomphant, describes not only the thrusting red element but also the triumph of its ultimate composition.

In 1975, prompted by Calder’s wildly successful project with Braniff International Airways to paint a DC-8 jet, French auctioneer and racecar driver Hervé Poulain commissioned Calder to paint a BMW 3.0 CSL. On 14 and 15 June of that year, Calder attended the unveiling of the car at the Le Mans 24-Hour race, where Poulain, Jean Guichet, and Sam Posey drove it; due to a mechanical failure, the car did not complete the race. Calder’s commission spurred an entire Art Car program at BMW. The artists who have participated include Frank Stella, Roy Lichtenstein, Andy Warhol, Robert Rauschenberg, David Hockney, Jenny Holzer, Olafur Eliasson, and Jeff Koons.

In 1973, J. Carter Brown, director of the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C., commissioned Calder to make a monumental sculpture for the museum’s new East Building, which was being designed by I.M. Pei. My grandfather proposed three different standing mobiles but eventually acceded to Pei and Brown, who had their hearts set on a large hanging mobile that would fill the atrium; Calder had wanted to do something less obvious, to be set in a visual dialogue with Pei’s dramatic design. My grandfather began to enlarge the approved maquette in his usual fashion, by making an intermediate-sized scale model to review and work out the kinks. When Pei and Brown saw this intermediate maquette, which did not suggest to them the lightness of the small model, they took the fabrication of the full-scale mobile away from Calder and his foundry and commissioned artist and engineer Paul Matisse to execute the precisely enlarged version. The monumental mobile that now hangs in the central court of the National Gallery’s East Building was completed and installed in 1977, after Calder’s death.

Beginning in the 1930s, Calder received considerable acclaim in The Netherlands. While the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam has long been recognized for their steadfast support of my grandfather’s work through both solo and group exhibitions, it was the Kröller-Müller Museum

in Otterlo that sought to make a permanent home for a monumental commission—one that was unfortunately never realized. In May of 1976, the museum proposed a sculpture for their garden; they invited my grandparents to Otterlo so that Calder could consider the site. My grandfather died not long after he had made a maquette and sent it to the museum. Rudi Oxenaar, the museum’s director, wrote to Louisa Calder, “I should tell you that Sandy’s model arrived here the day before we heard about his death. We are very happy and very sad to have it. I showed it to my trustees and I keep it in my office, see it every day and dream of things that probably cannot be anymore.”[16]

Centro Botín, Santander, Spain. Calder Stories. 29 June–3 November 2019.

Solo ExhibitionHauser & Wirth, Somerset, England. Calder: From the Stony River to the Sky. Exhibition catalogue. 2018.

Susan Braeuer Dam, For the Open Air

Jessica Holmes, More than Beautiful: Politics and Ritual in Calder’s Domestic Items

Solo Exhibition Catalogue“Calder in France.” Cahiers d’Art, no. 1 (2015). Edited by Alexander S. C. Rower.

Susan Braeuer Dam, Calder in France

Robert Melvin Rubin, An Architecture of Making: Saché and Roxbury

Agnès Varda in conversation with Joan Simon

Magazine, MonographMuseo Jumex, Mexico City. Calder: Discipline of the Dance. Exhibition catalogue. 2015.

Alexander S. C. Rower, Calder: Discipline of the Dance

Solo Exhibition CatalogueMusée Picasso, Paris. Calder-Picasso. Exhibition catalogue. 2019.

Bernard Ruiz-Picasso and Alexander S. C. Rower, Confronting the Void

Chus Martinez, No Feeling Is Final

Group Exhibition Catalogue